Like a champion tennis player or a wizened clockmaker, Taylor Swift has been training all her life to be the artisan she is today. A natural inclination toward synthesizing her problems through painful, earnest koans and an ease with uncomplicated melodies made the singer-songwriter a superstar in Nashville. But more fascinating than witnessing that perfect collision of lucrative skill sets is everything Swift has done to escape the genteel, apolitical perfectionism that made her famous: the unexpected twists the catalogue takes, the tiffs with her peers, the battles over authorship and respect. What does it say that one of the most successful pop singer-songwriters of the past decade is this person who’s had to pry herself painstakingly away from a politics of appeasement and inertia? Maybe her progression from writing songs about storybook romances to ones about not fitting into antiquated gender roles went swimmingly because it dovetails with a larger ideological shift, the incremental scaling back of the wants and needs of an entire generation from the dream of picket-fenced, pastoral living to a simpler fantasy: the desire to be truly free.

That’s what’s animating the historicity of folklore and evermore songs such as “marjorie,” “mad woman,” and “the last great american dynasty,” right? It must be more than just the keen interest in bloodlines and fairy tales the artist gleaned from seeing Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro’s mythic, gothic tandem of 2001’s The Devil’s Backbone and 2006’s Pan’s Labyrinth for the first time. Through musings on tragedy visited on women across history, Swift reiterates an idea that’s also present in the villainous snark of reputation, in the tense conversations depicted in the 2019 Netflix documentary Miss Americana, and in the margins of pricklier Lover tracks such as “The Man” and “I Forgot That You Existed”: If there’s no amount of money that can insulate you from an endless buffet of unwanted opinions about your body and art and politics, if the sun has never risen on a day in which women get a fair shake in society at large, then you may as well live how you want as best you can. It’s possible to go to your grave waiting for people to truly understand you; it’s more fun to let haters spin their wheels while you cruise through life goals.

In recent years, Swift has addressed this sentiment most astutely and directly in speeches and social-media posts in moments when she has been on the defensive, such as her war of words with Ye and her dispute with Scooter Braun over the ownership of her masters. The albums were for musings on love; the business discussions went elsewhere. So it seems notable that “Lavender Haze,” the first song on Swift’s tenth studio album, Midnights, cuts to the quick in dispensing with the unrealistic expectations that people have for pop stars: “No deal / The 1950s shit they want from me.” It’s a song very obviously about being watched — “I been under scrutiny / You handle it beautifully” — but Swift keeps the lines universal enough to apply to fans in all pay brackets.

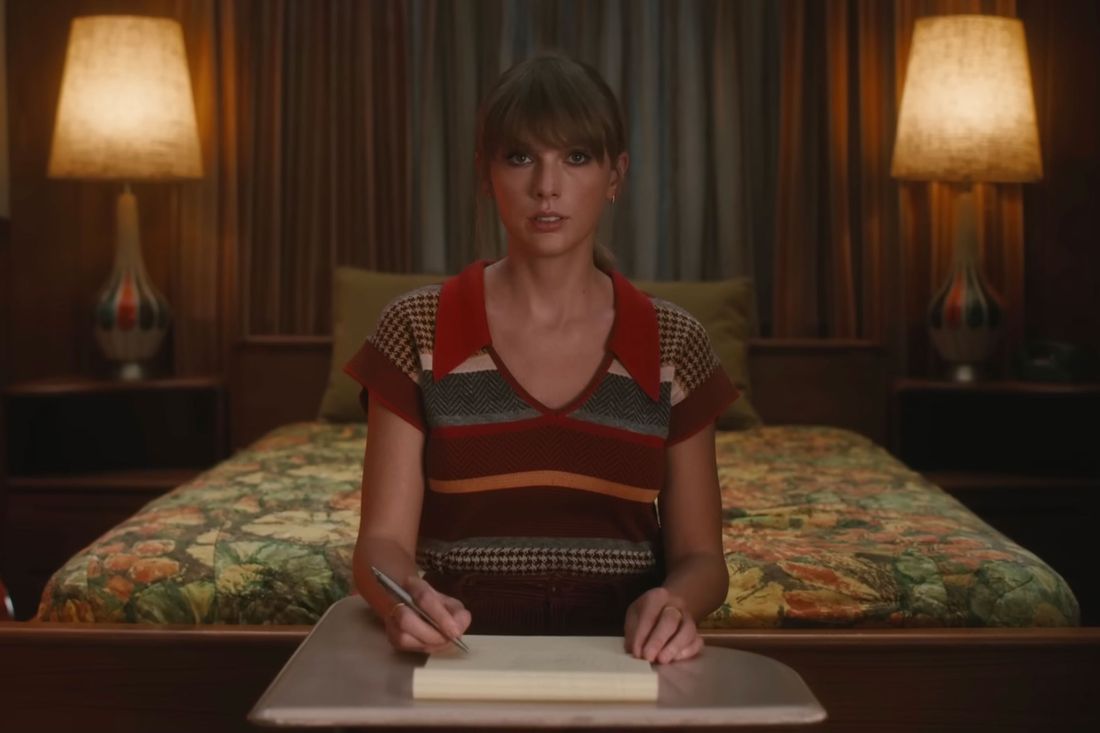

Midnights is a concept album that takes a peek into the life of the singer-songwriter on a number of eventful evenings in her development as an artist and as a significant other to the men in her past and present. It is both her second expedition into the episodic storytelling she played with last year in All Too Well: The Short Film, a visual companion to the ten-minute version of Red’s harrowing breakup tune directed by the artist herself, and an embrace of the cinematic ambitions you could always smell on her more refined character studies. The comedown from the obsessions with myth and ancestry of the previous two albums is jarringly personal, an autobiography in snapshots.

It’s also, by function of what’s happened to the singer since leaving her high-school boyfriend, something of a catalogue of the pitfalls of being ambitious, called to a nagging pursuit of greatness. Folklore and evermore threw the audience for a loop, flashing Swift’s flair for storytelling; she shook loose from the longstanding idea that her albums always recount the story of her most recent relationship, selling us rear-mirror breakup narratives from the comfort of monogamy. She was with Joe Alwyn when she wrote “the 1” and “’tis the damn season,” folk songs pondering what to do about your aching, discomfiting loneliness. That made her feel a little unknowable. Trickster that she is, Swift’s next big career play is another reversal: a return to blistering candor and synth-pop production. It was fun having no idea what to expect from her for a while. Midnights is pulling away from that, off dirt roads and back onto pavement, out of the cottage rental and back into the office. It approaches the business of realigning Swift with the sound of the pop charts with a skill informed by years on the job.

In the three years since the release of Lover, Swift’s last pure pop outing, mainstream music’s landscape has tilted. Billie Eilish swept top categories at the 2020 Grammys thanks to the claustrophobic electronics and wispy confessionals of When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?, and Olivia Rodrigo graduated from High School Musical: The Musical: The Series to Billboard year-end charts off the strength of last year’s pop-rock delicacy Sour. Lizzo, Doja Cat, and Megan Thee Stallion imbue bubbly, radio-friendly tunes with a rapper’s knack for wordplay. Swift has come out of the woods eager to get back to the business of seeping into nightlife, of pitching songs at sporting events and bar hangs. That requires a careful push this artist is uniquely built for as an incisive storyteller whose melodic instincts skew toward the impossibly catchy and whose pen was sharpened on country songs with mass appeal, such as “Teardrops on My Guitar” and “Tim McGraw” off Swift’s 2006 self-titled debut album.

The late-night theme of Midnights is a useful conceit that leaves a lot of space for variety in sound and subject matter. Nighttime is when we lie alone confronting our innermost thoughts, but it’s also prime real estate for partying. Midnights rests on this axis as it visits moonlit hours spent crying, fighting, dancing, drinking, and making out. Writing and production are handled primarily by Swift and Jack Antonoff, who came onboard for 1989’s “Out of the Woods” and worked on reputation, Lover, folklore, and bits of evermore. We’re mostly playing with the building blocks of 1989 and reputation, the chunky synths and taut drums of “Style” and the cockiness and trap beats of “… Ready for It?” and dipping into the woodland-folk aesthetic of the Lana Del Rey collaboration “Snow On The Beach,” which has that Christmas feeling present in folklore’s “mirrorball” and evermore’s “’tis the damn season.” “Bejeweled” revisits the maximalism of Lover. (You could slot a number of these songs on past Swift albums. Is this a side effect of the undertaking of rerecording the back catalogue to counteract Braun’s purchase of her masters?) It’s not really until one of the bonus tracks, “Glitch,” a jittery mix of electronic production and organic instruments, that Midnights gets weird. The vocal manipulation in “Midnight Rain” is something folklore and evermore guest Justin Vernon has been playing around with since the beginning of the past decade. The muted dance pop of “Labyrinth” takes after the sound Diplo and Skrillex fashioned together as Jack Ü.

Midnights is a mannered genre reset constantly threatening to cut in an alluring new direction. “Midnight Rain,” “Lavender Haze,” “Maroon,” “The Great War,” and “Glitch” all suggest this artist is capable of making a better R&B-tinged album than the worst songs from reputation led us to think; 11 or 12 of these could’ve been her Bedtime Stories. “Sweet Nothing” makes you crave more music in the stripped, stately style of “New Year’s Day.” The previous two albums told us Swift could be gripping without leaning on the gloss of “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” “You Belong to Me,” “Cruel Summer,” and “Blank Space.” Midnights trotting it back out feels safe. The writing is sharp, other than moments of nuclear-grade cringe like the “sexy baby” bar in “Anti-Hero, the Gwen Stefani–esque “Best believe I’m still bejeweled” line, and the cloying “Question …?” chorus. The production is tasteful, gossamer at its best and sometimes just skeletal. It attempts a curious if unsteady balance of sultry R&B and sophisticated synth pop that contends with the confident strut of Drake’s “Passionfruit” and “Hold On, We’re Going Home”; the heady, intoxicating gloom of Lana Del Rey’s Norman Fucking Rockwell!; the breathy vocals and unsettling quiet of the songs Eilish records with her brother, Finneas; and the stately songs about domestic bliss we’re getting from pop singer-songwriters like Nick Jonas or Harry Styles a decade or more into their careers. Midnights is Swift’s story, but it’s also serving as a notice that she could make “Adore You” and “Bad Guy” and “Race My Mind” and “Venice Bitch” if she wanted to, that she knows what you listen to and what you think of her and is locating the precise conglomeration of words and sounds to win you over despite your reservations — that this is and has always been her superpower.

That’s what’s going on in the album closer, “Mastermind,” a song about scheming to create the seemingly accidental meet-cute where you gain an audience with the love of your life for the first time, as well as in the single “Anti-Hero,” a kind of evil twin to the giddy pride of Lover’s “ME!,” in which Swift admits it must get pretty annoying trying to keep track of all her battles: “Did you hear my covert narcissism I disguise as altruism / Like some kind of congressman?” She’s conceding to being crafty, a terrifyingly effective overthinker and overachiever. The raw, self-deprecating humor of the single is as much of a unifying theme as the time of day when these incidents and observations took place. Swift’s giving herself a hard time and cussing up a storm. The coupling of coarser lyrics and R&B cadences was the foundation of 2017’s venting session, reputation. But where that album’s use of trap drums to feign defiance at a point where the artist needed to exact revenge on her enemies led to atrocities such as “Look What You Made Me Do” and classics such as “King of My Heart,” Midnights is more like an Extraordinary Machine moment, with the songwriter showcasing her ability to handle a wider array of syncopations. This opens the door to collaborations with beat-makers (including Kendrick Lamar collaborator Sounwave, who assists on “Lavender Haze,” “Karma,” and “Glitch”) that boost a song’s commercial appeal as much as they nudge the vocalist into different pockets. Like Fiona Apple’s “Parting Gift,” these songs are less interested in casting the two parties in a breakup as a victim and an aggressor than in poking around a dispute, making note of how it feels while it’s happening, what forces brought these two people together, and what’s causing them to clash now.

This is a different energy than the classic Swift breakup songs, in which an airtight case is presented against a defendant who doesn’t stand a chance. For the most part, the men here are a blur, a series of catalysts for the realization that you can find fulfillment outside the tradition of finding a mate to marry and have children with, which is pertinent in a successful year for people who have spent the past five decades chipping away at abortion rights. (It must be noted that bucking against expectations for young women is easier as a white woman who came from, and makes a ton of, money. So as we commend Swift for the versatile musical palate, and for the message that you don’t have to want or be able to reproduce to feel like a powerful and successful woman, it is every bit as valuable to assess the ways race plays into the reception of an artist’s bristling at these prescribed roles. Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey raised eyebrows blending pop and R&B. Swift gets perfect scores. That’s not a fair comparison, you may say. It was the ’80s and ’90s. In the “woke” ’20s, you can still witness the same fights: Does Lizzo’s music have soul? Is Doja Cat pop or R&B? You know who gets to jump around genres, who can traverse pop and country-music charts and award shows to universal interest and acclaim, and you know who causes a stir when they attempt to do the same.)

As Midnights jumps through time — observing a crushing moment in adolescence in “You’re on Your Own, Kid,” the desire to break out of the place you grew up in “Midnight Rain,” and the process of finding your confidence after a breakup years later in “Bejeweled” — the storytelling gets ambitious, a lot more like Richard Linklater’s Boyhood, Robert Altman’s Short Cuts, Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth, and the anthology New York, I Love You: stories woven from tinier vignettes, intersecting yarns about memorable evenings. Speaking at the Toronto International Film Festival earlier this year, Swift said she’d been inspired by timeless breakup narratives like Love Story, Marriage Story, The Way We Were, and Kramer vs. Kramer. And songs such as “Question …?” (“Good girl, sad boy / Big city, wrong choices”) would make serviceable rom-coms. But the overarching story told by stringing these stories together, and drifting from lust to love to loneliness and back again, starts to feel like something different than a High Fidelity, a tale told through terrible memories. We get a portrait of the endless, shiftless making, breaking, and remaking of an artist and an examination of the shapes her art has taken over the years. The lilting vocal delivery in “You’re on Your Own, Kid” is in conversation with the Swift of Fearless in form and in content. She’s singing the way she used to in the aughts about how the success she sought in those years carried her away from friends and family, the people she thought she would spend all her days in close contact with: “From sprinkler splashes to fireplace ashes / I gave my blood, sweat, and tears for this / I hosted parties and starved my body / Like I’d be saved by a perfect kiss / The jokes weren’t funny, I took the money / My friends from home don’t know what to say.” It’s a life of flux, of handlers and endless travel. The songs about the present quite literally crave inertia: Yes, “Karma” is a diss track; it’s also about cooling out in the house with the cat. “Sweet Nothing” suggests that, in spite of the job she chose and the fights she’s had to pick in defense of it, the singer-songwriter delights not in vengeance but in peace and quiet: “Industry disrupters and soul deconstructors / And smooth-talking hucksters out glad-handing each other / And the voices that implore, ‘You should be doing more’ / To you, I can admit that I’m just too soft for all of it.” Situating the boisterous Schadenfreude jam right next to the song about home as a refuge from drama reveals a deeper lesson in this album’s sonic, emotional, and chronological twists: It’s a lifelong process, figuring yourself out.