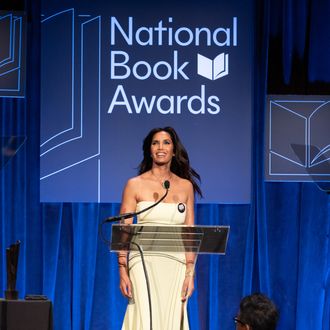

“For a bunch of writers, you’re pretty sedate,” host Padma Lakshmi joked at the 73rd National Book Awards, which were held in person after two years of virtual ceremonies. Book people manage to keep things an appropriate amount of cheerful, not that the event, or current publishing world, was sleepy at all.

Earlier in the day, PEN America published an open letter and spreadsheet tracking book bans in Missouri triggered by a state senate bill 775, which bars schools from giving students books that contain sexual content, a wide and vaguely defined enough net to catch The Essential Mary Cassatt, X-Men comics, and Rupi Kaur’s Milk and Honey. Several speakers sharply criticized school book bans; in her opening remarks, Lakshmi said that books were “under attack,” connecting the bans to the Florida Parental Rights in Education Act, known as the “Don’t Say Gay” law. American Library Association executive director Tracie D. Hall, who received the Literarian Award, exhorted the crowd: “Please, please stand against this effort to limit access to reading.”

Neil Gaiman, who presented the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters to cartoonist Art Spiegelman, joked that he was “proud” to see his book American Gods on the banned list; Spiegelman’s Maus, a genre-expanding memoir of his parents’ experience of the Holocaust, has also been banned by a Tennessee school board. (Spiegelman’s acceptance speech was the best tight ten of the evening, with crowd-pleasing jokes about publisher rejections, NFTs, and shocking nonagenarians into canceling their New Yorker subscriptions.)

It was a strong night for debuts and books long in the making, with many writers naming communities outside the publishing industry who helped produce their work. “I am the first Muslim and Pakistani American woman to win this award,” Sabaa Tahir, whose novel All My Rage won the award for young people’s fiction, said through tears to loud applause. She honored “my Muslim sisters in too many places to count who are fighting for their lives, their autonomy, their bodies, and their right to live and tell their own stories without fear.” The award for translated literature went to Argentinian author Samanta Schweblin and translator Megan McDowell for the short-story collection Seven Empty Houses, and John Keene’s Punks won for poetry, with Keene dedicating the award to “my ancestors, on whose shoulders I stand, by lineage and by association … particularly the Black, gay, queer, and trans writers, especially those who we lost to HIV/AIDS.”

Imani Perry’s South to America, a deeply researched memoir structured around Perry’s travels south of the Mason-Dixon Line, won the nonfiction award. “I write for my people,” Perry said. She quoted her grandmother, saying, “‘You weren’t born to live on flowerbeds of ease; these are not easy times’ … Let us meet the challenges of a broken world together.” The fiction award — the shortlist of which skewed toward debuts rather than established literary heavy hitters — went to Tess Gunty, whose novel The Rabbit Hutch centers on a run-down apartment building in a fictional midwestern city. “I was so convinced that there was no way this could happen that I did not prepare a speech,” Gunty said when she reached the podium — she went on to praise her fellow shortlistee’s books. (“I genuinely didn’t think I’d win,” she told me afterward. “And then my editor said don’t prepare a speech.” A few moments later, fellow fiction-award finalist Jamil Jan Kochai cut in to warmly congratulate her on her win.)

Outside the venue, about 20 members of the HarperCollins union, on the fifth day of a strike, passed out leaflets and union-logo buttons to attendees.

The message was noticed by the generally younger, more junior publishing-industry members who showed up for the after-party at 10 p.m. — when technically correct black tie started to give way to avant-garde party pants and micro Telfar bags. (According to two anonymous industry sources, “the normal people show up for the after-party.”) More union buttons on display; I heard that the leafleters had run out of them.

Of the awardees and presenters, both Ibram X Kendi, who presented the Literarian Award to Hall, and Lakshmi wore HarperCollins union buttons. When I asked Lakshmi about her decision to wear it onstage, she mentioned that her last two books had been published by Ecco, a division of HarperCollins. “A lot of people on those picket lines work very hard for my books, so it’s the least I could do to support them,” she said.