On the queer internet, Christmas is Carol season. Heralded as the gay Christmas movie, dykes of all stripes excitedly post about the 2015 film come December. There is Carol merch, with the image of the meet-cute between the titular Carol and Therese, whose love story is at the center of the film. And there are countless Carol memes all over social media for the entire month of December (the Instagram account godimsuchadyke, which has over 150,000 followers, begins posting them on November 1). In 2018, Autostraddle ran “30 Days of Carol,” with pieces like “Is Carol Mommi or Daddy” and “Carol Looks Ranked By the Degree to Which They Mark Therese As a Snack.” With all of that joyful obsession floating around the queer Zeitgeist, I was completely unprepared when I finally saw the actual film. What has come to be regarded as a lesbian holiday romance is actually a film about heartbreaking sacrifice and the impossible choices involved in living as your true self. It’s hardly the stuff of tidy memes.

The still image Autostraddle chose as the No. 1 “look directed at men” when “ranked by contempt” is rightfully recognized as Carol “wishing death upon a man.” In the image, Carol, wearing a fur coat and visibly crying, is pointing a gun and staring down a man who has wronged her. Nowhere in any of the 30 days is the reason for that look of contempt mentioned.

It is not a moment of pure misandry. It is a moment of pure desperation. The gun Carol (Cate Blanchett) has pulled is aimed at a man who has been hired to follow her and her lover, Therese (Rooney Mara), and get proof that they are sexually involved. In that scene, Carol has just discovered that audio tapes of her and Therese making love have been sent to her estranged husband, with whom she is embroiled in a bitter custody dispute. Carol realizes that she may have just lost the thing she loves most in the world: her daughter.

The feeling of betrayal and grief that washes over Carol when she opens the telegram informing her that the tapes have been sent to her estranged husband, who has filed for custody citing a “morality clause,” is one I experienced after I left my husband. I thought we were in the process of trying to amicably co-parent. Nearly a year after our divorce — and our joint-custody agreement — was finalized, a knock on my door changed all of that.

I felt as desperate as Carol did when she pulled out a gun and aimed it at a man. The custody case was like having the rug pulled out from under me in the most violent way. The message was loud and clear: You cannot leave this cis, straight marriage and go unpunished.

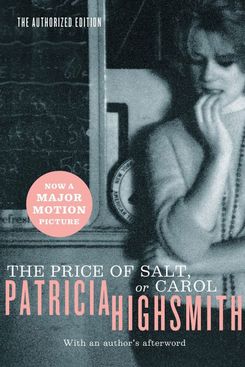

Carol the film is based on the 1952 novel The Price of Salt, by Patricia Highsmith. She originally wrote it under a pseudonym because she wanted to avoid being dubbed a “lesbian-book writer.” The novel became popular partly due to the fact that it was billed as one of the first lesbian romances that didn’t end in tragedy.

“The appeal of The Price of Salt was that it had a happy ending for its two main characters, or at least they were going to try to have a future together,” Highsmith wrote later in life. “Prior to this book, homosexuals male and female in American novels had had to pay for their deviation by cutting their wrists, drowning themselves in a swimming pool, or by switching to heterosexuality (so it was stated), or by collapsing — alone and miserable and shunned — into a depression equal to hell.”

Reading the book through a modern lens, that framing is hard to reconcile with the text on the page. The two women whose love story anchors the book don’t seem to like each other all that much, and their chemistry never really seems apparent to the reader. Carol is cold and quick to be angry at Therese over small and inconsequential things, like not wanting to play the piano when Carol asks her to. But a story about a lesbian love affair in which neither woman ends up going back to an unhappy marriage or settling into an unfulfilling life with a man she won’t ever truly desire was a victory during a time when homosexuality was still considered a mental illness and a criminal offense in some places.

But The Price of Salt is not a love story, nor is Carol. While the book and film contain a love story, at their heart they are about the impossible choices queer mothers have been forced to make in order to live authentic lives, and the ways they have been punished by society for daring to divest from desire for men.

That the film, in which it is implied that Carol and Therese end up together at the end, is still considered an epic lesbian romance by so many online queers is perplexing. Watching Carol, all I could see in that last scene — when Therese approaches Carol in a restaurant and the two lock eyes, Carol’s mouth beginning to turn upwards into a smile — was the sorrow. Yes, the women end up together, but at what cost?

“Carol looks out onto a time when same-sex relationships aren’t undermined by hardship, and one where the films about them don’t likewise undermine them by focusing too essentially on that hardship,” Moze Halperin wrote at Flavorwire upon the film’s release. “These characters fucking win.” Only someone who has never had to make the choice that Carol is faced with could declare that the hardship of that choice is a thing that can be minimized so as not to “undermine” a romantic relationship.

Carol had to give up the thing she loved most in the world — her child — in order to be true to herself. Many viewers have interpreted the narrative as Carol choosing to be with Therese over staying in her marriage to Harge, but that’s not actually the choice she makes. Carol leaves Therese in the middle of the night in a hotel room in the Midwest to go back to Harge so that she does not lose her daughter. She agrees to attend conversion therapy. She spends months trying to fit into the box she has been coerced into in order to not lose her child.

In the triumphant yet heartbreaking scene in the divorce lawyer’s office when Carol agrees to give up custody of Rindy to Harge, it’s not because she is choosing Therese. It’s because she’s choosing herself. “What use am I to her, to us, if I’m living against my own grain?” she says to the room, as her lawyer begs her to stop talking. It is only once Carol has chosen her own happiness and a desire to live an authentic life that there could be room to go back to Therese. Carol and Therese’s relationship is a ripple effect of Carol’s choice to walk away from the safety and security and restriction of a straight marriage, not the impetus for the exit.

The character of Carol Aird and much of the plot of The Price of Salt was inspired by Highsmith’s former lover, the Philadelphia socialite Virginia Kent Catherwood. Catherwood lost custody of her daughter in divorce proceedings that involved tape-recorded lesbian trysts in hotel rooms.

“When a woman lives with another woman by choice, or when a lesbian has or wants to have children without being a man’s wife, she is viewed as a threat to patriarchal law and order,” writes Phyllis Chesler in her 1986 book Mothers on Trial. “In creating a nonheterosexual family, the lesbian mother sets a dangerous example for all women. What if women refused to marry men who were not emotionally or sexually nurturing?”

Carol, as a film, asks these questions, too, albeit subtly. “Carol’s director, Todd Haynes … made the bold decision to allow Carol’s audience to laugh at men,” Heather Hogan wrote at Autostraddle, arguing that the film was overlooked for a Best Picture Oscar nomination because of its refusal to center the masculine experience. “Not with men. No, Haynes invited viewers to see the men in his movie — these husbands and boyfriends and duplicitous know-it-all notions sellers — through the eyes of queer women and to laugh openly at their silliness, unearned confidence, and expendability.”

It is, of course, okay that these men are ridiculed; they are the patriarchal figureheads who represent the oppressive expectations that Carol and Therese are living within. But by memeifying the romance between the two women and erasing the sacrifice that happens in order for their relationship to exist, it flattens them. They should be celebrated for finding love in a world that wants to deny them that opportunity, yes, but that love should be acknowledged for all the complexities that come with it.

Carol takes place in the 1950s, but my experience happened in 2021. It shocked me to see the ways these insidious, regressive ideas can still be weaponized against queer mothers when they decide to decenter cis men in their lives. That this film — which is beautiful, gutting, haunting, and incredibly moving — is still heralded as the ultimate queer love story may also say more about the dearth of representation than it does about the film itself or the intention of the filmmakers when making the movie. Because while straight people have multiple channels dedicated to telling uninspired stories of milquetoast relationships, queer people — and lesbians, in particular — still lack options.

There is Happiest Season, the Kristen Stewart vehicle that centers on a coming-out story in which Stewart’s character spends nearly the entirety of the film being treated like trash by her girlfriend on a trip home for the holidays. There is also A New York Christmas Wedding, which includes a baffling surprise pro-life “ghost of an aborted fetus” story line. And there is Carol.

It is no wonder that a community reads into the film what they cannot find elsewhere. But in doing so, they miss the point of the story.