David Crosby’s career in music should have ended in 1967. That was the day the other members of the Byrds came over to kick him out of the band.

“They drove up,” Crosby said in a 1971 interview unearthed by Barney Hoskyns for his book Hotel California, “and said that I was terrible and crazy and unsociable and a bad writer and a terrible singer and I made horrible records and that they would do much better without me.”

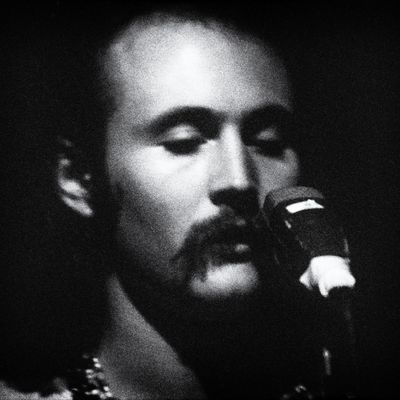

Crosby was already an icon at that point — clad in royal leather fringe at Monterey and one of the three or four flamboyant figures that epitomized the impossibly hip L.A. rock scene at the time. With Roger McGuinn, the Byrds’ mainstay; bassist Chris Hillman; soulful songwriter Gene Clark; and drummer Michael Clarke, Crosby and the Byrds created that watershed moment where jangly rock-pop met the seriousness of folk, forever embodied in the timeless passages of “Mr. Tambourine Man” (with lyrics by Bob Dylan) and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” (with lyrics by God).

But fans didn’t know that, far from his public image, Crosby was an entitled Hollywood rich kid with a moral screw or two loose. He contributed a just-this-side-of-toxic element to everything he joined and worked with, and only managed to be a success because of an undeniable voice that could meld effortlessly and alluringly with just about everyone he sang with. Crosby undermined his fellow members, fostered dissatisfaction for his own advantage, and was a compulsive manipulator. Beyond that, he wasn’t really a guitarist and didn’t write songs. The message from his fellow Byrd-mates, who knew him well, was — with the exception of the crack about his singing — right on the money.

But Crosby didn’t go away. A few years later, he found himself in a band with Stephen Stills (another guy with ego problems) and a by-all-accounts-nice British guy, Graham Nash, who’d been a major star in the Hollies. Their second public performance was at an intimate venue known as Woodstock. Crosby’s voice intertwined achingly and indelibly with those of Stills and Nash and occasionally took center stage, as on the brooding, seething “Long Time Gone.” Crosby, Stills & Nash — sometimes turbocharged with the addition of Neil Young into a juggernaut dubbed CSNY — became Crosby’s ticket to everlasting fame.

Crosby, whose death was announced this week, spent the next 50-plus years as a household name. He warred, split, and reuned with his bandmates. Their increasingly moneyed generation paid well to see their beloved CSN play “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” one more time, even as Crosby somehow ended his life whining about money. He became tabloid fodder, whether over repeated arrests on drug and weapons charges (and once doing time), getting a rich guy’s liver transplant paid for by Phil Collins, or contributing sperm to Melissa Etheridge and her partner for their child. Over the years his increasing size, shaggy mustache, and ring of frizzled hair became an iconic image in its own way — the caricature of the ’60s relic.

Crosby, like the Doors’ Jim Morrison, whose father was an admiral in the Vietnam War, had a background out of keeping with his hippie image. His father was Floyd Crosby, the Hollywood cinematographer who shot High Noon and took home one of the first Academy Awards for cinematography for his work on F.W. Murnau’s silent film Tabu: A Story of the South Seas. Floyd Crosby was also a descendant of the Van Rensselaer family, which remained prominent in New York for many generations. Young David grew up in luxury in Santa Barbara, but his social development was pretty checkered; all of the chroniclers of the scene say he spent time as a burglar during his limited matriculation at Santa Monica City College and abandoned a girlfriend after she’d gotten pregnant.

Crosby started out as a folkie — “a lecherous teddy bear with a playful brain,” as Hoskyns describes him. He fell in with McGuinn, who had come to L.A. from Chicago via some time in the coffeehouse scene in New York, and was at this point a veteran after several years with the Chad Mitchell trio. It was a key moment in rock history. The substance of folk music, as embodied by Bob Dylan, was about to make an irrevocable alliance with rock and pop. Crosby’s distinctive voice fit in well with McGuinn’s, and despite his other limitations, he quickly became a reigning figure among the pop-star sybarites who inhabited Laurel and Topanga canyons in L.A. at the time.

The Byrds are another of the famous early rock groups whose career was not charmed; they lacked the cohesive personalities and songwriting talent of bands like the Beatles or the Stones. There were fractious internal relationships and disputes about the band’s musical direction. Aside from McGuinn, all were rudimentary players. (McGuinn’s plangent, jangly Rickenbacker guitar is backed by the Wrecking Crew — the fabled band of L.A. session players — on the Byrds’ first album, right down to the reverberating bass line that marks the beginning of “Tambourine Man.”) The band fought a lot and was pushed around by outside producer Jim Dickson, who guided them, sometimes kicking and screaming, to popular success. With some canny song choices and the sounds of McGuinn’s ringing guitar, the Byrds were suddenly stars after “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” both went to No. 1 on the Billboard charts. But the group kept fighting; at one point, Clarke slugged Crosby. The podcaster Andrew Hickey unearthed this timeless explanatory quote from Clarke: “I slapped him because he was being an asshole. He wasn’t productive. It was necessary.” After many more fights and imbroglios too boring to go into here, the initial success stalled and Crosby was forced out. (McGuinn kept it going with evolving backing members for another half-decade.)

Crosby was bereft, but he still had his voice, and he took his status on the scene seriously. Among other things, he helped bring Joni Mitchell to Warner Bros., a label grasping to be hip at the time but still unsure about this sui generis singer-songwriter who defied categorization. Crosby lent his name as the ostensible producer of her first album, Song to a Seagull. (Mitchell would later say she didn’t like the way Crosby paraded her around as if she were his discovery.) They dated for a while, too.

That scene was remarkable — everyone from Frank Zappa to the Mamas and the Papas to Mitchell to Alice Cooper to Three Dog Night to the Monkees to Linda Ronstadt and the future members of the Eagles were running around, and in many cases boffing each other. Stephen Stills was on the outs from Buffalo Springfield, the band he’d been in with Neil Young. He and Crosby became friends and worked on songs together. By this time, Mitchell and Crosby split up and she began a serious relationship with Graham Nash, whom she’d met on tour. Memories differ whether the confluence came at Mitchell’s or Mama Cass’s Laurel Canyon house, but at some point Crosby and Stills began some impromptu harmonizing with him. Their voices melded impressively, and thus began the story of one of the most beloved bands of their generation.

It shouldn’t have worked. Stills was an army brat and far from a hippie radical; he was driven and a perfectionist. Nash had a fluty voice; already a star, he didn’t have to prove anything to anyone. With the manipulations of a very young David Geffen — just beginning his own remarkable career — and Geffen’s partner, manager Elliot Roberts, the band cut a remunerative deal with Ahmet Ertegun’s Atlantic records. Then things began to happen very quickly.

In the documentary Woodstock, the trio runs through Stills’s “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” “This is our second gig!” Crosby chortles to the crowd. And his moody reading of his own “Long Time Gone” is featured early in the film as well, making his voice a signal part in a key moment in the American counterculture. (Young joined the band for a second, electric set that night at Woodstock. The quartet would also play at Altamont, just before the Rolling Stones went on.)

The first, self-titled Crosby, Stills & Nash album, and the second, Déjà Vu, with the formal inclusion of Neil Young, let Crosby demonstrate that he, too, could deliver important songs as well as harmonies. “Long Time Gone,” “Almost Cut My Hair,” and Déjà Vu’s title song remain classics of the era, and virtually every song on the two albums — including “Helpless,” “Our House,” “Marrakesh Express,” “Teach Your Children,” and on and on — remains part of the collective cultural memory of the time.

Shortly after, Geffen constructed the first rock megatour, with CSN as the headliners. But again, internal divisions never let the band cohere. A third studio album, sans Young, would take seven years to come out. In between, Crosby and his former bandmates would release solo, duo, and reunion albums of widely varying quality. Crosby’s first solo album, If I Could Only Remember My Name, is dreary and ponderous, and it’s not helped by the myriad guest stars he drew in during its recording. The several albums he recorded with Nash are more listenable. Once in a while, CSN would bury their differences and tour again.

Crosby’s personality and shiftiness mark the memories of the time. He had a natural charisma, an infectious enthusiasm, and a sense of humor. Still, sentences like “So and so was wary of Crosby … ” appear again and again in histories of the era. Even by the standards of that colorful moment, Crosby’s sex life, his drug use, and ever-present entourage drew attention.

An early sideman to Crosby was guitarist Don Felder, who would go on to join the Eagles and write the music to the Eagles’ classic song “Hotel California.” “David Crosby … was the first person I’d ever met who used excessive amounts of cocaine,” Felder would write later, “and the energy that came off him in consequence was paranoid, tense, and fearful.” He didn’t treat women well, either. “David was charming around chicks,” a scenester is quoted in Hoskyns’s book. “But there was a revolving door with him — one girl in, one girl out. And if a girl got pregnant, he was mean to her and dumped her.”

His drug use quickly began to hurt both his career and the band’s. When the Byrds played The Ed Sullivan Show — at the time about the biggest opportunity a band could get — Crosby managed to get into a screaming match with the producer of the show, who turned out to be Sullivan’s son-in-law. As bassist Hillman told the story, the producer told the band to get the hell off of his stage, to a general round of applause from the crew. (Producer Dickson managed to salvage the appearance, Hillman writes.)

Crosby developed addictions he couldn’t shake, and compounded the matter with a fondness for guns; his run-ins with the law often included weapons charges, and were often massive self-owns. (One arrest came after he left a bunch of drugs and a gun in a hotel room.) He spent five months in a Texas prison, though he managed to avoid severe punishments in future arrests. There are few household-name stars whose image is so at odds with his real-life behavior.

Crosby ended his career in an odd place, privileged as ever but ravaged with the consequences of his difficult-to-detangle personal life, particularly the addictions. In 2000, a CSN reunion tour carried then-breathtaking ticket prices of $200. But the proceeds, like all of Crosby’s money, went for drugs. Even more cruelly, after so many years of bad behavior to his friends, bandmates, and family, he found himself isolated 60 years and a world away from the Laurel Canyon scene with a star or future star on every block. Near the end of his life, he acknowledged publicly, virtually all of the other artists he’d made his name with wouldn’t talk to him anymore.

But Crosby was loved by CSN fans, of course, and his voice on the CSN and CSNY albums remains in the consciousness of two-plus generations now. And for all the foibles he and many of his coevals displayed, they were finding their way in a new world and in a new medium, with few blueprints. In the best of his work, you can hear the idealism of the time. In interviews late in life, Crosby was still willing to spar and settle old scores, but he also displays bits of hard-earned wisdom as well. “He admits he has been an ‘asshole’ for for much of his life,” an interviewer in The Guardian wrote in 2021, but also elicited this quote from one of music’s ultimate lifers: “The important stuff in my life isn’t the troubles I’ve had, it’s the magic that’s happened to me to enable me to make all this music.”