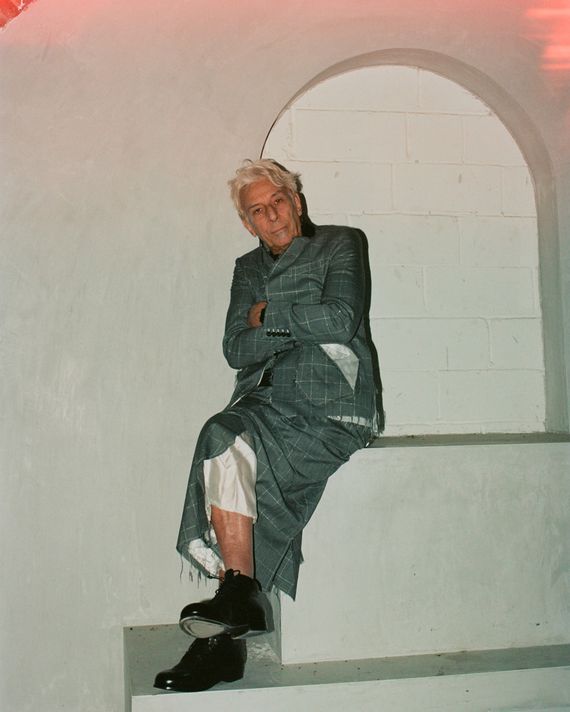

John Cale has impeccable timing. The Welsh multihyphenate — a veteran singer-songwriter, composer, producer, session player, style impresario, drone lord, and poetry enthusiast — moved to New York City at the dawn of the ‘60s hellbent on making contact with the city’s frothing downtown music scene and spent much of the decade seeding ideas that would grow into vital musical traditions across the rest of the century. The “dream music” Cale created with violinist and filmmaker Tony Conrad, multi-instrumentalist and tape whiz Terry Riley, visual artist and vocalist Marian Zazeela, and composer and performance artist La Monte Young in the Theater of Eternal Music is arguably the big bang that birthed the next six decades of advances in ambient, drone, and minimalist music. A short stint on bass, viola, and piano in the Velvet Underground — a rock band but also a carnival but also an Andy Warhol-approved art project — produced thorny delicacies like “I’m Waiting for the Man” and “White Light/White Heat” as well as tense, noisy fever dreams like “Heroin,” “Sister Ray,” and “Venus in Furs,” striking a balance between arty inaccessibility and clarion catchiness that inspired generations of punk-rock idols.

After being edged out of the Velvets in 1968, Cale embarked on a delightfully unpredictable solo career. The long jams on 1969’s Terry Riley team-up Church of Anthrax worked out some of the ideas German bands like Faust and Neu! would get to in the ’70s. The 1972 instrumental opus The Academy in Peril saluted composers Cale studied on the way to earning the Leonard Bernstein scholarship that brought him to America; 1973’s Paris 1919 applied arranging skills to gorgeous baroque-pop tunes. 1974’s Fear invited members of Fairport Convention and Roxy Music to dip into the glam-rock sound David Bowie perfected (while Bowie expressed his appreciation for the Velvets). The constants in a catalogue that’s impossibly vast and always changing are a resistance to cheap thrills, a desire to unite musicians across disparate areas of expertise, and a ceaseless commitment to doing whatever it takes to get the song across the finish line.

Mercy, Cale’s 17th solo album, keeps the traditions in place. On the surface, you could call the new album his foray into atmospheric electronic-dance music and syncopated drum programming. On another level, it’s the textbook collaboration between a minted music legend and a stream of younger admirers: Mercy includes guest spots from Actress, Laurel Halo, Weyes Blood, Tei Shi, and Dev Hynes, a testament to the breadth of the marquee artist’s tastes and sphere of influence. The lyrics suggest a unique relationship to chronology. Old ghosts mingle with new terrors. The dubby Animal Collective collaboration “Everlasting Days” rejects the comforts of nostalgia, and then “Night Crawling” delivers a recollection of partying so hard with Bowie that it ruined plans for music. “Time Stands Still” ponders ecological disaster over hip-hop beats with Sylvan Esso, and then “Moonstruck (Nico’s Song)” thinks back on the Velvet Underground’s “Femme Fatale” and the triumph and tragedy Cale witnessed as Nico’s friend, collaborator, and sometime producer between the late ’60s and her untimely death in 1988.

I spoke to John Cale in a Zoom call earlier this month about defying expectations and distorting time, about the journey from being shouted at by offended early audiences to being lauded as a musical pioneer, and was thrilled by his almost scientific outlook. He frames rock and roll as a string of lab experiments, a succession of speed demons attempting to break the sound barrier. He grasps the value of popular music as a vehicle for ideas and intriguing feats of sound design, and he sees over the partitions separating genres. At 80, he’s worked with your legends’ legends’ legends. He also keeps up with new rap.

Mercy is your first album of all new material in a decade, since Shifty Adventures in Nookie Wood. What pulled you back in?

I have a whole bunch of reasons. I got caught up in writing a bunch of songs. I finished them, I got them all lined up, and then I found that there was a little added flavor needed. I had everything done, and then I went back and listened and decided which ones could use some other vocals, and they really benefited from the effort. My vocal palate changed a bit. What happened had something to do with having to expand my vocal tastes, and that’s where we started. It expanded and it got better. I was glad I did. It was really a good use of my time with the pandemic. I got a lot done. I was glad I buttoned down.

It feels like you’re wrestling with the state of the world over the last ten years on here — you know, our descent into darkness.

A bit of it, yeah.

You’re also revisiting the past. When did you write “Moonstruck (Nico’s Song)”?

About eight months ago.

Did revisiting Velvet Underground tapes for Todd Haynes’s film put her on your mind?

It did have something to do with it, absolutely. I didn’t have the wherewithal to say, “Okay, now I’m going to write a song about Nico.” That’s not the way it happened. After I’d done it, suddenly I realized: “Wait a minute. I know who that song is about. It’s someone I know very well.” One of the funny things about having worked with Nico for a long time and what came out of it all was I noticed that people thought that the songs were better. Her songs had gotten better. I was really glad to hear that.

I used to have this bartender in Manhattan who’d put on The Marble Index to clear people out around closing time.

[Laughs] Bartenders always have the answer.

The pivot from the folk songs of Chelsea Girl to the dirges of Marble Index, Desertshore, and The End… is such an unusual trip. As someone who was around for the making of those albums, as a producer and a player and a friend, how do you recall that journey?

Well, there was some pain involved. They came after a lot of thinking about what she wanted to do. Jim Morrison made her work. Nico thought, “Hey, write the poetry. Get the poetry done first, then we can add the melodies and all that.” She used to run around carrying a notebook all the time, and it paid off.

I was watching an old David Bowie interview the other day, and he spoke about trying to catalogue the unknown and forbidden in the ’70s. “I just wanted to experience everything,” he said. Your new song “Night Crawling” memorializes him. He must’ve been important to you as someone who grew up equally anxious to expand your intellectual horizons.

There were all these shifting boundaries. In the time that we had to address what he wanted to do about music and what I wanted to do about music, unfortunately … I didn’t know what I was trying to really get going, because there was, first of all, too much partying going on. I wanted to do some work, I wanted both of us to work, and I think he did too and we just never got to it. We got some work done, but not enough at all.

When you got to New York in the ‘60s and met John Cage and La Monte Young, Cage was having some success in advancing a different understanding of how much or how little noise can qualify as impactful art, enough for me to encounter 4’33” as a student in the ‘90s. Young seemed like the tougher sell. I’m curious about the early drone experiments.

We didn’t do many concerts, first of all, because not too many people wanted to sit and listen. But there was one concert we did at Rutgers. I was playing viola. Tony [Conrad] was bowing an acoustic guitar. La Monte, I think, was playing saxophone, and Marian [Zazeela] was singing. La Monte decided that the sax was not the answer, and we had all these problems with intonation. He was trying to make the sax work, and Tony and I had the guitar and the viola, and we were much closer to the intonation problem and much more attuned to it than La Monte. La Monte had decided that we were going to do some concerts using just intonation.

How did the audience receive this?

Oh, it was terrible. They were yelling and shouting. I think some of the faculty were there. They were all yelling at La Monte, saying, “La Monte, you should be ashamed of yourself!” La Monte said, “So should you.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about how technical innovations trickle down into popular music. Were you hip to what Lee Perry and Augustus Pablo were doing in the ’70s with the delay and phaser effects in dub?

Yes, Lee Perry was definitely in the picture. I think there were a lot of people in downtown New York that were tripping the light fantastic when George Maciunas was there. A lot of the music that came out of the Lower East Side was very scraggy. It was really undisciplined. But I think with Tony there was a lot of science involved. His basis for doing what he did was science, so it was always fun to be around him just messing around with sound and theory. He goes right into the theory side.

There’s something everybody discovers at some point about the power of music to shift our sense of time, whether it’s the inertia you might feel listening to a drone, or the way dropping a bit of delay on a drum can feel like recoil. But the academic appreciation for this is spread unevenly. I think hip-hop samples have this power, but the teachers I came up with thought sample loops were a debasement of music. Yet there were titans of 20th-century music working wonders with repetition.

You’re right. There was a lot of academia behind especially what Tony was doing, and he guided La Monte through a lot of experimentation. La Monte was trying for the same thing, but he didn’t quite get how to do it. Tony did know how to do it, but didn’t quite know how to address it. That’s not a good explanation. Tony was a mathematician, basically, and his mathematical explorations fit in really well with the dream music that we were messing with.

I think your expertise is making the highbrow feel accessible.

We were trying to do a lot of things all at once, and it all came from strange surroundings. We decided that Columbia really had something going for it. Columbia University had a practice of experimenting with distorted time … is one way of putting it. I was interested in how time became distorted. It was a wild, wonderful ride, and we got quite a lot done. I don’t think anyone went further than La Monte and Tony. I think they’re still trying to get up there.

I’ve been listening to Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music lately and wondering whether the sound takes a bit of inspiration from the Theatre of Eternal Music. Did you feel like Lou was keeping up with your work in the years when you weren’t speaking?

No, I didn’t. I didn’t get the sense that he was really bent on getting to the same place that La Monte was at. La Monte was really pressing down on what we didn’t get done when we had the Theatre of Eternal Music. A lot came out of it. I think it’s true of the whole scene with Tony and La Monte and Terry Jennings. They all came out in places where they didn’t expect. They tried and they did some amazing things, but I don’t think that they got to where they wanted, even though I admire everything that they did. It’s an incomplete journey.

A pioneer’s job is just to push further into the unknown. You’ve done that. You produced debut albums for Patti Smith and the Stooges and most of the first one from the Modern Lovers. Were these artists coming to you for a certain stamp of authenticity, or was it that you’d figured out how to balance chaos and catchiness?

I think both of these are true.

Did the early punk records sort of validate what you were doing in the ’60s? Did you feel like, Okay, people did hear us?

No. Those guys were trying it on. They were trying really hard to get somewhere based on emotion, the Stooges, especially. When I first saw the Stooges, they really moved audiences. At that point, there were a lot of bands around that really went after muscular music that, again, didn’t quite get there. But in the best of the Stooges, it was there. Finding out what really moved them around was a task. It was well worth doing.

While you worked with punk artists, you also made appearances on folk albums by Nick Drake, Julie Covington, and Kate and Anna McGarrigle.

It seemed to be a mixture of those things that really worked for a lot of musicians. You had to work at it. When you get to hip-hop, you’re on your own. There’s great ideas going on there and you’ve got to know what you’re looking for.

What are the hip-hop records that impacted you?

Apart from Snoop and the successful ideals of early hip-hop, when you’ve got Earl Sweatshirt and Vince [Staples], you’ve got a lot of things to draw from. There are a lot of very clear-eyed concepts of what a song and a melody and a chorus and all of that means. They mess with everything. They mess with time. They mess with pitch. They really open the doors for chaos. They make chaos romantic.

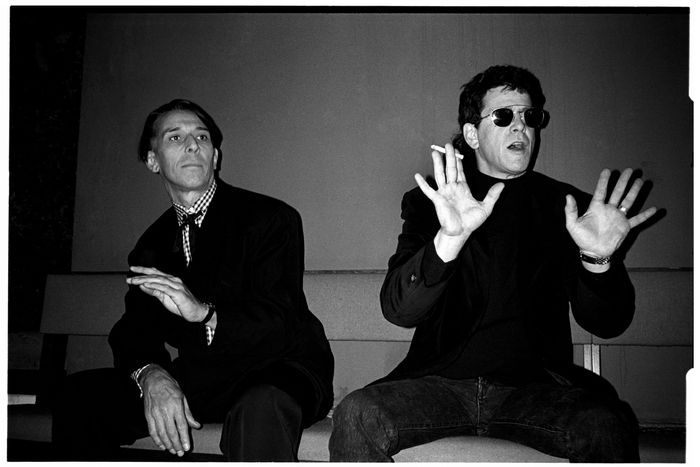

In the late ‘80s, you reunited with Lou Reed for Songs for Drella, to pay tribute to the late Andy Warhol. What was it like stepping into the studio to make another album with him?

Well, there’s a certain amount of gritted teeth, but then at the same time you have work to do. Every time I say that, there’s a groan I can feel coming along. But you always learn something. And you knew that when you worked with Lou, you were there for the work. You weren’t there to mess around. He was always generous with his inspiration. The thing that I always looked to him for was the way the words worked for him. It didn’t work the same way for anybody else.

Did you feel like there was more music left for the two of you to make together after that?

I suppose so. I suppose so. But … it was sleepwalking, really.

The Velvet Underground took a syncretic approach to rock shows, setting the stage for the multimedia concert experiences we have now. You ran into the Grateful Dead a bit, who, I think, shared your taste for upending tradition but had a perpendicular ideology to yours. How did you feel about the Dead? Lou famously swore off all of San Francisco.

We didn’t really get to explore or exploit any of the attention that the Dead were getting. I found out about the Dead later on, how they were sort of really bending the idea of jazz. There was really something going on there, and it’s also the same thing that was going on with La Monte. La Monte was part of a really studied jazz school.

Were you surprised by the quieter sound of the ‘69 Velvet Underground album or could you feel the band pulling that way before your split with them? The audience gets a loud, reckless album in White Light/White Heat, then the next one flips everything on its head.

It’s chronologically understandable. When it was done, the time that it was done and the period in which it was done, it made perfect sense. One of the things that Lou was really expert at was lyric writing, fitting into the job that he had. He had a job at Pickwick Records, and it was about writing folk songs, basically. They’d tell him what they wanted him to write and he did it.

So, you think the third Velvets album was meant to put the spotlight on his songwriting?

Yeah. He was definitely interested in that.

Do you think he needed to have the experimental guy out of the picture to accomplish it?

Lou and I were very two different musicians, which was exactly the point. We found common ground with what we wanted to do together, and it worked out until he wanted to get fame faster — and I wanted to tread on norms. Whatever came once I left was what he was after, I guess?

Do you ever regret being challengingly particular sometimes about your artistic vision, or do you sleep easier knowing you were consistently true to yourself?

No, I don’t regret it. I’m sure I could’ve made things easier for myself, made more money or whatever, but that’s not very interesting to me. It’s about finding something new at every turn, if you can. I don’t see the point of doing something for the sake of ease. That’s not for me. I don’t necessarily start out with the intention of being contrary, or “challenging,” as you put it. I do have to admit I seem to end up there more often than not.