It’s easy to forget, now that all meaning has been wrung out of the term, that cancellation is a joke about television — a reference to dropping someone from your life the way a network might drop a failing sitcom from its schedule. And it’s TV, always more agile in reacting to real-world developments, that’s been the chief source of stories about characters getting canceled as the term became a refrain in culture-war fodder. Procedurals like The Good Fight and Law & Order have centered cases on fap-happy comedians and slur-spouting professors, while sci-fi shows like Black Mirror and The Orville have presented tortured allegories about people getting killed by hashtags or lobotomized at the behest of a downvoting public. And that’s just on an episode level. Series like Hacks and Alaska Daily built callouts into their very premises, citing them as the impetus forcing their disgraced heroines to start over in humbling new gigs. When Apple got into the streaming game in 2019, its flagship offering was the star-driven The Morning Show, a sleek drama taking place in the aftermath of the firing of a famous news anchor who was not unlike Matt Lauer.

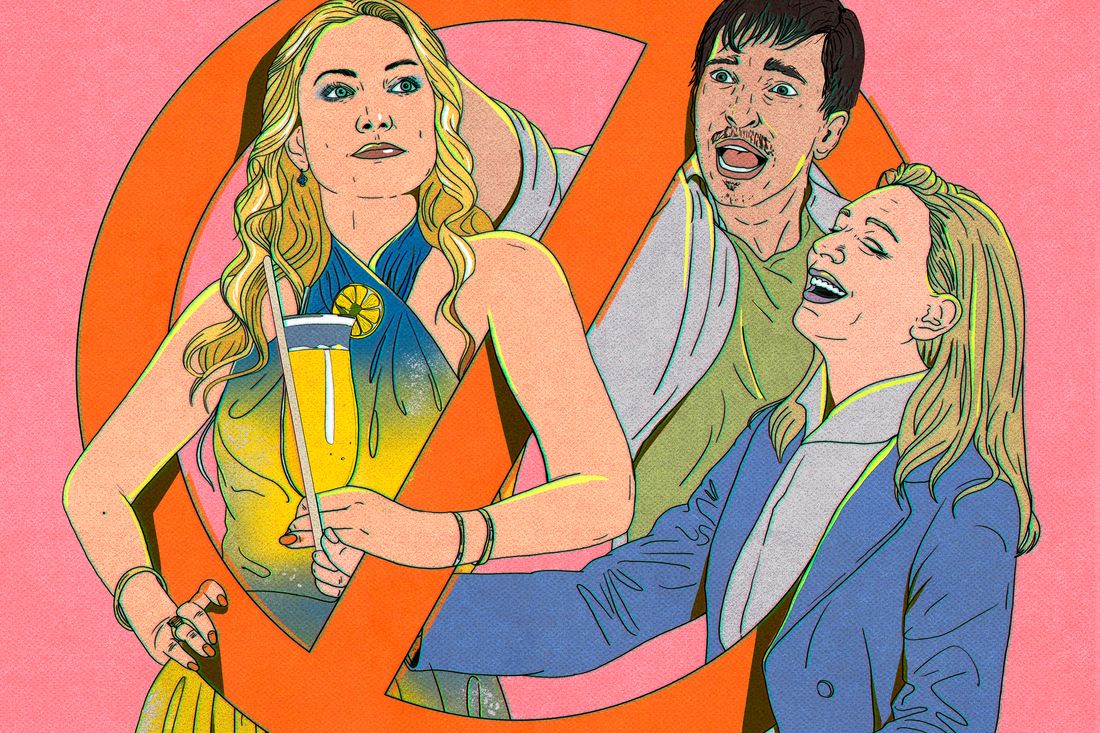

Movies move slower and take longer, and it’s really only in the past year that cancellation has filtered through in any significant way on the big screen. In the creepy hit Barbarian, Justin Long plays AJ Gilbride, a smirking sitcom actor whose career implodes after a co-star comes forward with allegations of sexual assault. He soon had highbrow company in the form of Lydia Tár, the brilliant, egomaniacal conductor portrayed by Cate Blanchett in Tár, who experiences a similar fall from grace after the suicide of a mentee brings to light her history of using her power to leverage sexual favors from young women. Joining them is Kate Hudson’s Glass Onion character, Birdie Jay, a preening media influencer who lost her job at a magazine after an incident involving blackface, reinvented herself as a leisurewear mogul, and now teeters on the brink of another disgrace owing to her company’s use of a notorious sweatshop. These aren’t ripped-from-the-headlines re-creations of actual people, and they’re not just excuses to deliver referendums on cancel culture — which may be why they’re so delicious. Freed from the burdens of topicality, characters in the process of being canceled make for great material.

Part of the appeal of cancellation, not as a social-media phenomenon or some sign of a generational divide but as a spectacle in itself, is that it offers a different angle on celebrity. Over decades of cinema, we’ve gotten examinations of what it’s like when fame slowly fades away (Sunset Boulevard or, more recently, Babylon); of fame as a trap (Hollywoodland or The Rose); of fame being tested by scandal (Notting Hill, Beyond the Lights). But getting ejected from the ranks of the notable like Lucifer being cast out of Heaven, plummeting down so fast your ears pop? That abruptness is an effect of the digital age, and while we’ve had plenty of opportunities to witness this process from the outside in the past few years, to see it explored in fiction is unexpectedly fascinating. These characters aren’t changing or growing in ways we’ve been taught to expect — in fact, while these movies all tease the potential for a moment of redemption, they also all withhold it. It’s the world that has changed, leaving them in a panic over actions that once might have been brushed out of view of the public.

The rise of the recently ousted celebrity as a type shouldn’t come as a surprise at a moment when everyone’s enraptured with glossy satires about the rich like The White Lotus, Succession, The Menu, and Triangle of Sadness. While those comedies of affluence and awfulness provide opportunities to bask secondhand in luxury while sneering at its beneficiaries, there’s a defeatism running through them, an acknowledgment that, short of acts of God or apocalyptic violence, there’s no touching those people or toppling the structures they’re perched at the apex of. The characters in Barbarian, Glass Onion, and Tár may seem to enjoy a similar degree of privilege, but they’re not untouchable. Watching AJ belt out a tune in his convertible on the Pacific Coast Highway, or Birdie Jay swan along poolside in an Andrea Iyamah bikini, or Lydia Tár arrive home to her brutalist Berlin apartment provides some of the same have-your-caviar-and-eat-it-too pleasures with the knowledge that a comeuppance is on its way. And that while it may not mean much in terms of systemic change, they’ve earned it. For AJ, it comes almost immediately: His introductory sing-along gets interrupted by a call from his representation informing him that he’s being accused of rape. Two scenes later, he’s scurried off to Detroit in an attempt to stave off financial ruin by selling an investment property and unknowingly inserts himself into a horror scenario — no more bouncy music.

Chalk it up to the difference between the genuinely wealthy and merely famous: Money doesn’t care if you’re despised. These characters may be well off by normal standards, but they’re still only rich-adjacent, which turns out to be a precarious position once things start going bad. Birdie, having already gone through one downfall, is ready to trade in the remains of her reputation and take the bullet for her company’s labor violations in exchange for a payout from her biggest investor. AJ scuttles around the basement of his Brightmoor murder house with a measuring tape, seeing dollar signs instead of how hilariously unnerving it is, and Lydia makes a surreal escape to her childhood home in Staten Island. You could accuse these movies of demonstrating a certain amount of wish fulfillment by having their invented celebrities face more serious consequences than most real ones accused of similar misdeeds. (Lauer, for one, retreated to the Hamptons estate he’d eventually sell for more than $33 million.) Still, Lydia Tár remains employable in the end, even if it is as a conductor of video-game scores, and the explosive events in the finale of Glass Onion seem likely to deflect attention from Birdie’s latest wrongdoings. AJ does meet a grim fate, but it’s thanks to an inbred mutant rather than studio executives or public boycotts — even in fiction, there’s a limit to what we can, or want to, imagine about what comes next. What is captivating is the fall itself and, alongside it, the borderline sociopathic behavior of these characters who’ve all managed to convince themselves they aren’t responsible for the wrongs they seem pretty clearly to have committed.

In each case, their crimes mostly take place offscreen, which helps these movies get away with treating their characters as the stuff of dark comedy. But guilt seeps in at the edges. Lydia has hectic dreams about the young conductor she took under her wing and into her bed, then cut off and blacklisted, leading to her death by suicide, while AJ tells his version of what happened to a friend at a bar — “She just took some convincing, is all” — the camera holding on his increasingly uncertain expression as he tries to bro his way through a self-defense. There is something wistful about these bursts of self-awareness. It’s an impulse that has been mistaken by some, particularly with Tár, for empathy for its protagonist’s predicament, though what the movie really does is humanize her. She runs outside to throw up when confronted with a mirror of her own behavior, but there’s no reason to believe she wouldn’t still do everything possible to evade blame the next day.

It’s natural to want to understand the everyday monsters so many of us encounter in less glamorous form, to process them into fiction. But the stickiness of movies like Barbarian, Tár, and Glass Onion, which have lingered in the cultural conversation, is also a reminder of how much easier it can be to tell stories about violators than ones about their victims. She Said, a staid drama about the breaking of the Harvey Weinstein story, languished in theaters this past fall, somehow seeming both too soon and too late. A far better Me Too movie was Sarah Polley’s Women Talking, though it took place in an insular Mennonite colony whose residents were so far removed from Hollywood they might as well have been on the moon. Even so, the wrenching debates it depicts about what to do in the face of systematized abuse are likely to be seen by a fraction of the audiences for the previous titles — even the box-office-unfriendly Tár. These films also left the abuse offscreen, though in their case it was to allow the characters who endured it a place at the center. We are so early in figuring out how to tell these stories, how to process the covering up of misdeeds and the imperfect crowdsourcing of justice to address it. The promise of Schadenfreude is a more straightforward proposition.