By the early ’90s, Miramax, the Tribeca-based company founded by Harvey and Bob Weinstein, had elbowed its way to the center of the indie-film world, as Michael Schulman notes in his book Oscar Wars: A History of Hollywood in Gold, Sweat, and Tears. But Harvey wanted to break out of the “art-house ghetto.” One way he did that was by vigorously campaigning for Oscars for films like My Left Foot and The Crying Game, the latter of which saved the company from financial catastrophe. Then came Pulp Fiction.

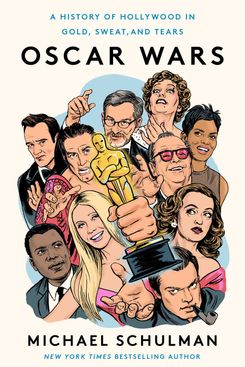

An excerpt from 'Oscar Wars: A History of Hollywood in Gold, Sweat, and Tears'

Through aggressive acquisitions, Miramax had established its identity and knew exactly what kind of movies it wanted to put out. There was “literary” foreign fare such as Like Water for Chocolate, which became the highest-grossing foreign film in a decade. (To celebrate, the company threw a banquet in TriBeCa for a thousand guests, who were invited before dinner to watch actress Claudette Maillé re-create her nude horseback scene on the West Side Highway.) And there were grungy, provocative American movies like Kevin Smith’s Clerks and Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs.

A motormouthed, kung fu-obsessed cinephile, Tarantino had quit high school and in 1984 started working at the Video Archives in L.A.’s Manhattan Beach. There he found his cadre of movie geeks and began writing Reservoir Dogs, a bloody, postmodern heist film made for $1.3 million. With its B-movie violence, blaring seventies soundtrack, and revenge-of-the-nerd nihilism — all ending in a hailstorm of bullets — it was an unapologetic assault on the refined art house aesthetic. After one Sundance screening, a spectator asked, “So, how do you justify all the violence in this movie?” Tarantino shot back, “I don’t know about you, but I love violent movies. What I find offensive is that Merchant Ivory shit.”

Reservoir Dogs left Sundance without a distributor, but Miramax’s acquisitions team implored Weinstein to take a look. He thought that the gore would alienate women, a thesis that held up when his wife and sister-in-law left the room after the ear-slicing scene. Tarantino objected, “I didn’t make it for your wife!” After a standoff, Weinstein blinked. He opened the movie in October 1992, ear-slicing included. It grossed some $2.5 million — hardly Crying Game money. Meanwhile, Tarantino, with an option from TriStar on his next project, holed up in a one-room apartment in Amsterdam, hopped up on twelve cups of coffee per day and filling composition notebooks with indecipherable scrawl. After three months, he emerged with Pulp Fiction.

The script — nonlinear, ultraviolent, with a leather-clad character called the Gimp — was too weird for TriStar, but Miramax production head Richard Gladstein gave it to Weinstein, who was catching a plane to Martha’s Vineyard. Within three hours, he called Gladstein and said, “The first scene is fucking brilliant. Does it stay this good?” An hour later, he called again: “Are you guys crazy? You just killed off the main character in the middle of the movie.” Keep reading, Gladstein urged him. “Start negotiating,” Weinstein said. He called back a third time. “Are you closed yet?” he asked. “Hurry up! We’re making this movie.”

The film shot in the fall of 1993, with John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson as hitmen and Uma Thurman as a crime boss’s wife. At Cannes, the Weinstein brothers — newly flush after selling Miramax to Disney — showed up with the Pulp gang. The movie hit Cannes like dynamite. Crowds chanted Tarantino’s name. “Quentin brought back that thing that only had existed theretofore in the seventies, the idea of the rock-star director,” says his then publicist, Bumble Ward. On Tarantino’s way up to accept the Palme d’Or, a woman shouted, “Pulp Fiction is shit!” He flipped her off and said, “I don’t make movies that bring people together. I make movies that split people apart.”

That fall, Pulp Fiction went to the New York Film Festival, where spectators included Jeffrey Katzenberg, Demi Moore, and Tom Cruise. During the scene in which Travolta stabs Thurman in the heart with a syringe of adrenaline, a woman screamed, “Is there a doctor in the house?” A diabetic man had fainted. Miramax sent the guy home in a limo, and the film resumed. The incident made headlines, but not everyone was convinced. “It could not have been a bigger — in my opinion — stunt,” says Fine Line’s Liz Manne, who was sitting a few rows behind the fainter. “Either that or Harvey made the most of an opportunity that arose organically. Many people in the industry thought that it was a fake.”

Pulp Fiction opened in October 1994 on 1,100 screens and made back more than its $8.5 million budget on the first weekend. “The hero ain’t the hero. The villain ain’t the villain. And the outcome of the story might happen an hour before the end. It’s defying everything,” Weinstein told the press. A true cultural phenomenon, Pulp Fiction became the first independent film to blast through the $100 million mark, and Tarantino the rare director famous enough to host Saturday Night Live. He was the face not only of the exploding indie movement but also of Miramax. “I’m their Mickey Mouse,” he’d say.

Pulp Fiction was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, among twenty-two total nominations for Miramax. “I’m drinking sweet vintage champagne through the faucets of Miramax,” Weinstein told the L.A. Times. (The press knew he was good copy.) His competition was Forrest Gump, a feel-good studio drama that located America’s soul in a sweet simpleton played by Tom Hanks. At more than $600 million worldwide, it was the highest-grossing film in Paramount’s history. Gump vs. Pulp reflected the two antipodes of American movies: big-budget Hollywood versus the rude, ascendant indies. “They kept calling it the David-and-Goliath year,” says Bumble Ward, “but it really was a sort of litmus test: Are you a Forrest Gump person or are you a Pulp Fiction person? Are you groovy or not?”

Although Weinstein had about half of Gump’s campaigning budget, he used his resources shrewdly. Miramax staff would visit the motion picture retirement home in the Valley, where some elderly Academy voters lived, and, according to Tarantino’s agent Mike Simpson, “have lunch with little old ladies and make a personal connection with each one of them, saying, ‘Watch the movie and vote for our film.’” The tactic, like others for which Miramax became notorious, wasn’t new, but Weinstein was relentless. The studios were now showering voters with so much swag — including Disney’s fifty-dollar coffee table books for The Lion King — that the Academy had to warn against items that “tread dangerously close to the definition of a bribe.” “I’m always going up against the huge Hollywood establishment, and this time it’s no different,” Weinstein said mid-campaign. “You have Bob Zemeckis and Tom Hanks, who could both be mayor of Beverly Hills.”

The Gump campaign was overseen by Cheryl Boone Isaacs, Paramount’s head of worldwide publicity and one of the few Black executives in Hollywood. A few years earlier, Weinstein had tried to poach her, saying, “You’re the kind of person Miramax would love,” but she declined. Now she was in direct competition with him. “It was heated,” she recalls. “Pulp Fiction was the darling of the New York press, which didn’t make life easy by any means. I remember saying to the staff, ‘Okay, this is the deal: every nomination that is offered, I want it.’” Although Gump got thirteen nominations, Boone Isaacs wasn’t taking anything for granted. “We had already known he was good at this,” she says of Weinstein. “But I didn’t think he was any smarter than I was, to be honest.” (Two decades later, she became the Academy’s first Black president.)

In March 1995, the Miramax crew touched down at LAX like a band of renegades from a Tarantino movie. Two nights before the Oscars, Pulp Fiction swept the Independent Spirit Awards, but Weinstein predicted, “Monday night, we’ll be the fucking homeless people.” Like Citizen Kane, Pulp Fiction lost every Oscar but the original screenplay award, which Tarantino shared with his old video store chum Roger Avary. (In another Citizen Kane echo, the two had squabbled over Avary’s credit.) Onstage, they looked like crashers from a skateboarding contest. Avary, a long-haired art school dropout, announced, “I really have to take a pee right now.”

Miramax had taken over Chasen’s, the storied West Hollywood eatery that was about to shut its doors. The party was a kind of Irish wake, both for the restaurant and for Pulp’s Oscar chances. The guests reveled in being the cool-kid losers — even Madonna, who watched the telecast from the party. When Gump won Best Picture and one of the producers invoked its values of “respect, tolerance, and unconditional love,” she heckled the screen, “What about mediocrity?”

By 12:30 a.m., the party was packed, the atmosphere unhinged. When Courtney Love, in mourning for Kurt Cobain, recognized the woman sitting next to her as Lynn Hirschberg, the journalist who had written a damning Vanity Fair profile of her, she said, “You have blood on your hands,” grabbed Tarantino’s Oscar off the table, and tried to clobber Hirschberg with it, as the director scrambled to intervene. After Love gathered herself and left, Tarantino turned to Hirschberg and quipped, “If she had killed you with an Oscar, it would have been like a scene from one of my movies.”

Late into the night, Weinstein told the New York Observer that he hadn’t given up on those Oscars after all: “At 4 a.m., we’re going to Hanks’ and Zemeckis’ houses. We’re taking them back.” He smirked. “And if they don’t give them up, we’re going to get medieval on them.” He enjoyed playing troublemaker, but he knew what to keep hidden. Among the revelers was Uma Thurman, who later revealed that, amid the Pulp Fiction juggernaut, Weinstein had assaulted her at his suite at the Savoy: “He pushed me down. He tried to shove himself on me. He tried to expose himself. He did all kinds of unpleasant things. But he didn’t actually put his back into it and force me. You’re like an animal wriggling away, like a lizard.”

The next day, he had sent her yellow roses and a card that read, “You have great instincts.”

Excerpted from the book OSCAR WARS: A HISTORY OF HOLLYWOOD IN GOLD, SWEAT, AND TEARS, by Michael Schulman. Copyright © 2023 by Michael Schulman. Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.