Either because of the unruliness of midwestern spring, this being my last semester teaching in my current department, or that my wife is due in exactly two months, nothing really feels  predictable right now. Hence six books that, in very different ways, teach you how to read them. A triumphant return by a legendary poet is joined by an artists hybrid love letter to New Orleans. A debut novel that examines the possibilities we allow in our lives complements a selection of essays that find infinite possibilities in lifes most microscopic moments. Meanwhile, two of our brightest critics set their sights on art monsters and the nature of artistic affection. Life is full of uncertainties. Hopefully they arent boring.

In this interactive art book, Cammock, a Turner PrizeÔÇôwinning multidisciplinary artist, casts the city of New Orleans as both a case study and a chorus of voices. Newspaper clippings, letters, song lyrics, and other documents are paired with both contemporary and archival photographs. ItÔÇÖs the latter that does the most work visually. Vantage points cycle through ground-level close-ups and expansive views of sky; subjects are framed in intimate profile when they arenÔÇÖt being documented through dispassionate mid-shots. The project is tied together by the story of the late Elizabeth Catlett, a sculpture and civil rights activist who taught at Dillard University and was commissioned to create a monument to Louis Armstrong in the cityÔÇÖs Congo Square. CammockÔÇÖs portrayal of CatlettÔÇÖs fierce intelligence adds color to the portrait of New Orleans and its place in Black history.

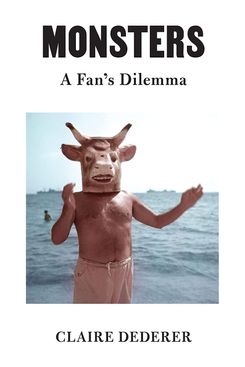

DedererÔÇÖs latest ÔÇö a collection of essays that expands on her instant classic Paris Review essay from 2017 ÔÇö is unique in that it acknowledges oneÔÇÖs personal response to art by ÔÇ£bad peopleÔÇØ instead of the false choice of focusing on the art or cancellation. Because she has written memoirs, Dederer is probably used to the personal being confused with a lack of seriousness, and Monsters is equally impatient with the pretension of art fans who claim their admiration for works is purely on the merits as it is with those who claim to punish artists for bad deeds regardless of personal preference. But Dederer is also a critic, which means she is implicated and that she is comfortable with showing her work. The result is some of the best writing on classic enfants terribles such as Nabokov, Sylvia Plath, Roman Polanski, Pablo Picasso, and Woody Allen in ages. Outside of giving the cultural class permission to feel something about great works by terrible people, her individual calculations on whether itÔÇÖs possible to divorce works of art from the deeds of their creators prove bracing.

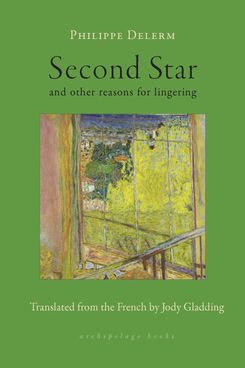

The ÔÇ£literary snapshotsÔÇØ of Delerm, an acclaimed French essayist, are a refreshing stateside arrival of a novel form, and puncture any conceived notions about length and brevity. Rather than a slice-of-life tale composed of small moments, or a fragment intended to create a sense of a broader theme, Delerm works like a poet, each entry effectively an ode to its singular place within consciousness. Readers might push back on the universality of ÔÇ£Munching a Turnip,ÔÇØ or ÔÇ£The Leathers of Hazel Wood,ÔÇØ but the book leans more toward collective experience due to DelermÔÇÖs panoramic sense of observation and his startling points of connection. Like being in the thrall of a masterful novel plot, or the structure of an abstract film, the journey is the point: ÔÇ£And itÔÇÖs not so bad, all things considered, to be sure of nothing, to be alive and to agree without really knowing to what.ÔÇØ

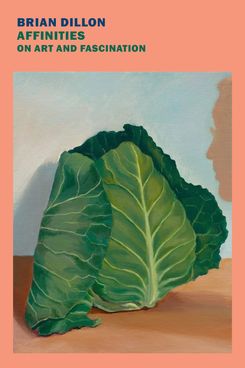

Dillon completes a hat trick of smart, idiosyncratic nonfiction books with what is perhaps his most ambitious: a criticism propelled by vibes. Taking affinityÔÇÖs random and spontaneous nature as his starting point, he goes about catching lightning in a bottleÔÇöarranging his appreciations of artists and images in a way that feels consistently surprising yet strangely, somehow related per that other definition of affinity, ÔÇ£a similarity of characteristics suggesting a relationship, especially a resemblance in structure.ÔÇØ The essays have enough rigor to stand on their own, but the thrill of reading lies in tracking the hazy connections that Dillon has stitched together. Even the introductory essay ÔÇö usually an establishment of terms ÔÇö appears throughout the book in numbered segments to up the ante, the author turning his disorienting critical experiment on himself. As original as any book to come out in recent memory and, to this writer, DillonÔÇÖs best.

The turn in this debut novel ÔÇö occurring in a conversation between the unnamed narrator and her therapist ÔÇö is gasp-worthy, and will likely cause plenty of backward-flipping through its pages. How did Harrison achieve this spectacular feat of emotional withholding while also making readers feel so much? For our narrator, a mixed-race photographer, sure. But also her husband, Asher, a Jewish menswear designer who serves as her more intuitive foil; her sister, Viola, estranged and born again in the South following the death of the womenÔÇÖs parents and younger sibling; and her Black student Noah, who has a random run-in with police that lands him in the hospital with a bullet lodged in his chest. Harrison dodges trauma-plot sinkholes through her insight that the thorniness of our national conversation can give otherwise rational people ammunition to misinterpret their lives. NoahÔÇÖs advice to the narrator upon seeing her randomly on the street post-hospital ÔÇö ÔÇ£DonÔÇÖt be afraidÔÇØ ÔÇö is meant for her as well as us.

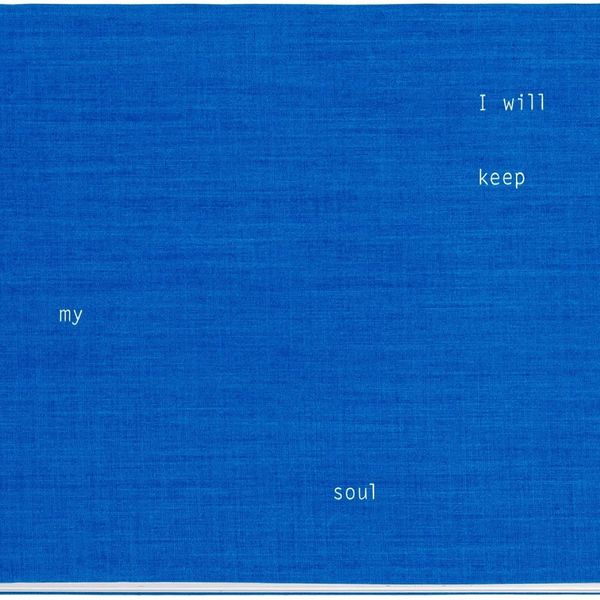

This new poetry collection from Myles is their first since 2018, which is just to say that the notably prolific writer, who has also written several volumes of fiction and essays, is on their time, not yours. A ÔÇ£Working LifeÔÇØ takes you where Myles feels like, for however long they feel like it, and in whichever direction. This is harder than it looks. The ease of MylesÔÇÖs lines ÔÇö the way words break in two to calibrate rhythm and speed, or how the number of words per line expand and single out to play around with tension ÔÇö belie great skill. But the difference between poets isnÔÇÖt just style; itÔÇÖs personality, or oneÔÇÖs outlook on life. MylesÔÇÖs is one of the most distinctive, and insightful: ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs my disease / that I think /┬áIÔÇÖm responsible, that itÔÇÖs / a class, itÔÇÖs not / a reading, IÔÇÖm not / in charge.ÔÇØ