This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It’s hard to argue that there’s much fresh energy among news podcasts of late. The genre’s modern generation largely came of age across the Trump era, and it is striking how little it has evolved — both in form and in options — in the years since. To be sure, this doesn’t necessarily constitute a problem. For most earbud-slinging Americans, The Daily remains the most listened-to news podcast, followed not far behind by the familiar public-radio stylings of NPR’s Up First, and I don’t really get the sense that either program is wavering anytime soon. I myself remain a regular listener. But the settled nature of the category has resulted in a lack of novelty. A healthy media ecosystem is defined by its dynamism, and in my mind, the news-podcast genre has been overdue for something new.

That newness may already be here. Lately, my desire for exciting, new news podcasts has led me to an unexpected source of adrenaline. Quietly but surely, more of my listening has been drifting toward a source I never expected to develop a relationship with: The Economist, the stodgy, 180-year-old British weekly specializing in global affairs.

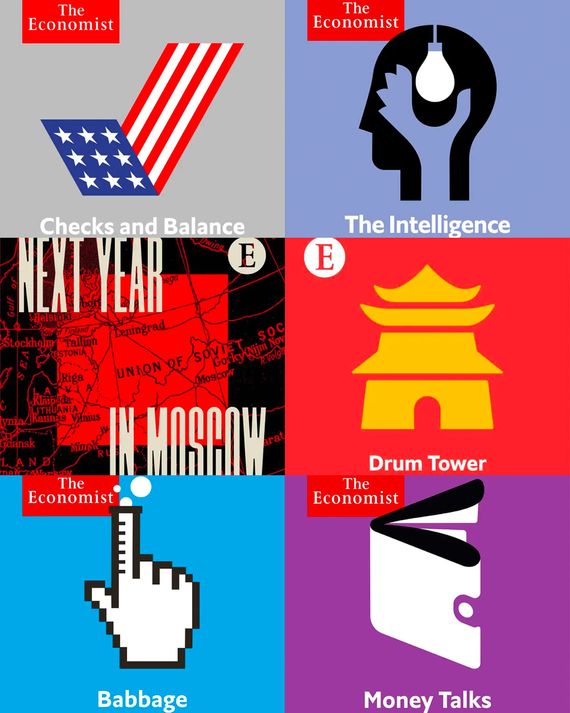

Now, let me be clear: The Economist’s podcasts are explicitly not for everybody. Aside from their intended audience of present and future power elites, the shows feel most suited for the kind of nerds who would happily submit themselves to the cult of Adam Tooze (if they aren’t already sated by his own wonky economics podcast, Ones & Tooze, of course). The Economist’s growing audio portfolio primarily consists of several regularly publishing news shows that span the publication’s range of staid interests: The Intelligence (its take on the daily news podcast), Checks and Balances (U.S. politics from a U.K. perspective), Money Talks (self-explanatory), Babbage (science and technology), and Editor’s Picks (selected articles read aloud). None are particularly groundbreaking on paper. In fact, they are almost throwbacks, somewhat devoid of the affable presentation and emotionality of modern American news podcasts. They are incredibly British — which is to say genteel, studious, a little awkward, and dry as sand.

They also seem to be catching on. A spokesperson for The Economist tells me that its podcasts averaged around 25 million downloads in March. That’s still a fraction of what you’d expect from a heavyweight like, say, the New York Times (125 million, according to the industry-measurement firm Podtrac), but the larger story here is one of growth. The network has more than doubled its unique listenership, another salient audience metric, over the past three years, from around 2 million in 2019 to about 5 million today. The momentum is inspiring further investment. “This is our fastest-growing platform,” said Bob Cohn, The Economist’s president, over email. “We’re thinking hard about how to keep adding to the portfolio, likely in the back half of this year.” This makes for a striking contrast with other parts of the industry, which has been facing cuts and show cancellations in the midst of navigating a difficult economic environment.

The Economist’s history with podcasts extends far beyond this contemporary iteration. The august British magazine was actually part of the original wave of hype surrounding the medium’s inception in the 2000s, back when many observers thought that all this podcast stuff was going to be the next major frontier in media. (That prognostication wouldn’t really be validated until another few hype cycles, of course. Podcasts are always the next big thing, just as podcasting has always been dying.) The publication’s earliest efforts were as rudimentary as you would expect, featuring audio files of professional newsreaders reading stories from the print magazine aloud.

The magazine’s modern podcasting era earnestly began in 2019 with the launch of The Intelligence. Like the publication as a whole, its entry into the daily-news genre is heavy on analysis and proudly esoteric. A recent episode bundled a comparative analysis between India’s and Indonesia’s economies with stories about abandoned Russian luxury yachts and a logjam of dead fish in Australia. The Economist’s institutional weight is routinely made apparent. During the opening stages of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, The Intelligence attained the distinction of being among the first platforms — and certainly the first podcast — to secure a sit-down with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, with Economist editor-in-chief Zanny Minton Beddoes personally making the trip to Zelenskyy’s war room to conduct the interview.

I’m no Tooze bro, but there’s something distinctly appealing about the somewhat unmodern nature of The Economist’s podcasts. This might simply have to do with how it breaks from much of the contemporary news-podcast environment, which tends to interpret the podcast medium’s oft-touted “intimacy” by collapsing the gap between the show and the listener. You’re conditioned to develop a feeling of closeness with a daily news podcast and its hosts. In style, there is often a lot of hand-holding, informationally and emotionally. This framework of news communication is understandable within the modern American context, reflecting a public-service-driven desire to meet as many listeners as possible on their level. But there are ways in which it can sometimes be off-putting, even condescending. In contrast, The Economist’s podcasts are pleasantly aloof, even indifferent. Rather than broadly calibrating for whatever common-denominating level of knowledge listeners might have with the subject matter, they often project a sense that it’s less about them meeting people where they are than it is about people meeting them at theirs.

This quality connects The Economist’s podcasts to something I’ve always felt was fundamental about the appeal of great talk podcasts. To put things crudely, the best of such shows evoke a sense of voyeurism, for lack of a better word, or the sensation you’re listening into a conversation that’s not entirely for you and that’s operating somewhat beyond your level of knowledge. It’s the same pleasure, I think, that drives the counterintuitively wide appeal of the BBC’s relentlessly heady In Our Time, which features the presenter Melvyn Bragg in continuous, rotating conversations with academics about all sorts of esoteric subjects, from the Irish rebellion of 1798 to the religious philosophy behind Deism. Less universally, it’s also the same pleasure that drives my personal affinity for eavesdropping on scores of roughly made independent podcasts featuring people talking in detail about something I know little about. (Not long ago, I was introduced to a podcast all about the lumber business, and for a small stretch, it was all I listened to when I wasn’t checking out shows for my job as a critic.)

All this seems to resonate with John Shields, who leads The Economist’s audio division. “I think the flow state of podcasts is being in that sweet spot where you’re learning about something but also doing a bit of work to fill in the blanks,” he said after hearing my spiel about voyeurism. Shield took his analysis a step further, drawing a natural link between the esoteric appeal of wonky podcast programming, The Economist’s included, and the titanic popularity of true crime within the medium. “People can be so snooty about true-crime podcasts,” he said. “But the genre is very much about how it’s your job as the listener to do work. That’s where the satisfaction comes from.” In other words, the appeal lies in having to close the gap between you and the show by yourself.

Beyond counter-intuition, there’s another reason to pay close attention to The Economist’s nascent adventures in audio. It has begun to display an expanding sense of ambition at a time when podcast studios have grown increasingly circumspect.

Nowhere is this more expressed than in The Economist’s push into audio documentaries. Where numerous other publishers are pulling back from the often expensive limited-run-series format, chiefly in response to the tough economic picture and the speculative podcasting bubble’s recent deflation, the magazine appears to be laddering up its operations.

Last summer, The Economist launched The Prince, an eight-part series tracing the rise of Chinese president Xi Jinping. Hosted by Sue-Lin Wong, then the magazine’s China correspondent, the project delivered an expansive look at one of the most powerful people in the world in the run-up to a defining Party Congress that saw him consolidate power even further. The Prince was a hit for the publication, driving 9 million downloads since its fall release and drawing admiration from a broad coalition of listeners. Shields tells me that the former CIA chief David Petraeus sent an email to Beddoes complimenting the show, and the audio documentarian Dan Taberski of Running From Cops and 9/12 fame was spotted talking up the podcast on Twitter. “I ate it up,” Taberski told me, adding that he would gush if he ever met Wong. The publication later capitalized on The Prince’s success, spinning out another regularly publishing news show, Drum Tower, focused on covering China. “That’s been our most successful launch so far,” said Shields. “In terms of the speed with which it’s caught up with our other shows, and the enthusiasm it’s generated among China watchers and general audiences alike.”

The magazine has since deepened its push into the audio-documentary format. Last month saw the release of Next Year in Moscow, which follows the Russian-born reporter Arkady Ostrovsky as he explores the effects of the Ukrainian conflict on everyday Russians who oppose their country’s invasion. What’s notable about Next Year in Moscow is how it feels, by itself, like an evolution of The Economist’s own audio aesthetic — more sonically immersive, attuned to a sense of emotion. “Nearly 12 hours had passed since the invasion began. I wanted to see how the city had changed, but it hadn’t,” he narrates in the first episode, conjuring a vivid sense of place. “Outside there were no signs of a coup, no obvious evidence that the world had transformed overnight. The same shops, the same traffic, the same cafés.” Ostrovsky’s delivery is quiet, matter-of-fact. In places, you could reasonably mistake the series for a grim journal or a dark travelogue.

“Tone is something we talk about a lot,” said Shields of the new project. “We have big arguments all the time about whether a bit is too overdone or too sentimental or too wonky, so much so that we lose the audience. But ultimately, we’re trying to be authentic to The Economist tradition, where we’re working to engage both hemispheres of the brain simultaneously, and it’s an iterative process.”

Aside from representing another step forward in the publication’s grasp of the medium, Next Year in Moscow also reemphasizes the innate appeal of The Economist’s podcasts. The series is dense, heady, and challenging in a way that prompts you to match its vibe. Each episode, and each new project, feels like an evolving variation of that sensibility, with genuinely exciting effect. For the first time in a long while, the news-podcast genre feels like it has a shot of fresh energy once again. “It’s still early days for us, but we’re pleased with how successful things have been,” said Shields. “We’re keen to find other spaces where we can own territory that others aren’t necessarily going to occupy.”