Even if you don’t know Vanessa Chester by name, her face — and voice — will be immediately familiar. Chester has been a working actor for decades, landing roles in national commercials, huge blockbusters like The Lost World: Jurassic Park and heartwarming classics like A Little Princess and Harriet the Spy. She has been on the front lines of a shifting industry — one that depends on actors willing to perform countless auditions for free while, over time, relinquishing certain reliable forms of long-term compensation like traditional residuals. Chester agreed to talk with Vulture about how much things have changed for her and many of her peers who make up the Screen Actors Guild just as the union decides whether to walk away from their jobs to secure a better deal with Hollywood.

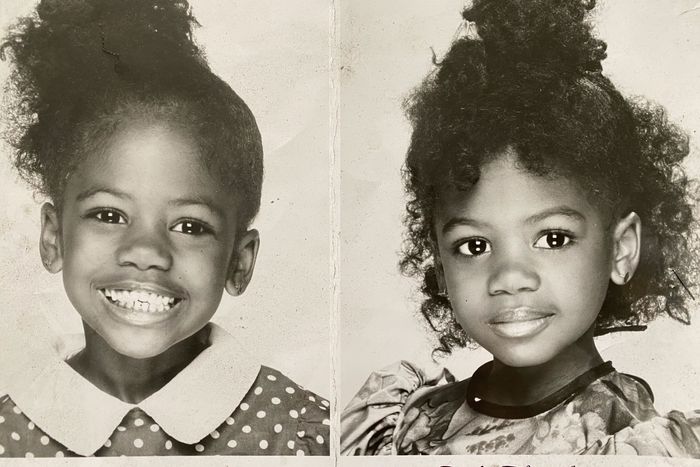

When I was 3 years old, my mom found an ad for a talent agency in the back of the New York Times and, according to her, we went to the office and came out with contracts. I am the daughter of Guyanese immigrants, the first person in my family to be born in the U.S., but the next thing I knew, I was doing commercials in New York and Sesame Street. I remember being in kindergarten like, “I know that Snuffleupagus is two people, and you don’t.”

After a while, my agent suggested we move out to California to see what it’s like. It was the recession of the early ’90s and my mom had just gotten laid off, so she figured we had nothing to lose. We came out to California for what was supposed to be six months, and the first commercial I booked wasn’t even my audition. We’d given a friend a ride to a commercial audition for Softsoap. All of the girls were in pageant dresses, and I showed up in overalls. The casting director liked that I looked like an actual kid and invited me to audition — I ended up booking it, and that friend never spoke to me again. Later, booking a Barbie commercial was the game changer. We didn’t have a ton of money, so when they took us into this room with every Barbie and told us to pick one, I was like, “Mom, what’s happening?”

Looking back, I realize my mom was making a huge sacrifice for us to be there, because she was a single mom and my main caretaker. My mom never felt entitled to the money that I earned—she worked when she could, but she never wanted to hire nannies to stay with me on set, she wanted to be there with me. And I knew that there were things we had to pay for: headshots, cars, rent, all that. But because she fostered a trust with me as a child, and provided me with a lot of financial transparency, I had an understanding that, while I wasn’t the breadwinner, the extra money I was contributing helped my mom, and that felt good. At one point I even made a little “house fund” box where I planned to collect enough money to buy her and my brother a new house.

Only when I was around 8 did I start to understand money and how to make some. I convinced a little girl in the neighborhood to pick flowers — literally vandalized the landscaping of the Oakwood apartments where we lived — and we created little bouquets. Then we went and knocked on people’s doors and sold the flowers back to them for a dollar or two. I came home and told my mom I’d made $27. She was upset that I’d vandalized the property but impressed that I understood flipping something for a profit. So she went to the resident adviser and arranged for me to have a lemonade stand at the pool every weekend.

This is all to say that numbers have always been a part of my life. I ended up studying economics in college — right when it was time for me to start taking over my own finances. At 18, you get your Coogan account, which is basically a trust fund that’s set aside for child actors to make sure your earnings aren’t all spent. When I got it, I remember being terrified. I had a friend who got his and bought a car. I bought a new cell phone for $300 and decided not to spend any more. It was weird to me. For so long, my main focus was honing my craft. But I started to realize that this is a business too.

Technology has changed that business. When I was younger, I remember hopping in a taxi with my mom after school. I’d be in my uniform, and we’d go to some office building. There weren’t fax machines and email, so there was no way of acquiring a script prior to an audition. I would learn my lines there. Everything was basically a cold read. That’s definitely no longer the case. Self-tapes have always been around, but they were never the primary source of sampling actors’ talent. Then in 2020, we couldn’t meet up, so self-tapes were the only way to audition. At first, it was a safety precaution, but then once protocols started to lift, things didn’t shift.

Of course, there are positives to self-tapes. It’s great to not have to get on the freeway and be stuck in traffic for two hours. But I’m one of the lucky ones. I can just go into my office and tape, then watch The People’s Court. (There are people who still need to find child care for their 2-year-old, because that 2-year-old wants to look at the Zoom when they’re recording.)

And while they say there’s more accessibility in self-tapes, the thing with being in the room is not only did you get a chance to interact, you got feedback, you got redirects, you got notes. For newer actors, it’s a chance to build a relationship with a casting director. But now, it’s just throwing things at the wall, hoping something will stick. If you have the funds, you can pay for someone to coach you so you’re perfect. You can pay for a self-tape studio so you’re going to turn in an incredible tape.

Other costs have shifted onto the actor. Before 2020, I think I bought one cartridge of printer ink per year, because casting would provide the scripts for you. Now, I’m buying one at least every month or every other month. For a group of laborers who hustle to make the necessary $26,470 to be eligible for health coverage — and many don’t reach the threshold, meaning they need to have a survival job on top of acting — the options are to get out of the industry or go into debt while hoping the next audition is the one that catapults you.

Technology might be one of the biggest threats to the integrity of my business. One casting director said that technology has now afforded her the ability to see up to 500 self-tapes. How does anyone watch 500 three-minute tapes?

AI is new. It could change the way I relate to my “likeness” — a word that is uncomfortably, maybe even intentionally, vague. One thing that I’ve been told is I have a really unique voice. I was at Comic-Con two years ago, and this guy was like, “This is really weird, but were you in Jurassic Park? I heard your voice, and I recognized it.” And with AI, it seems like they’re saying, “We understand your value, we understand what you have to provide, but we want to capture it and not pay you for it. Are you cool with that?” No. If you can take my voice and someone else’s lips and someone else’s hair, you can get the best part of all the things we’ve developed to make ourselves unique. How do you then quantify how much of my likeness is in that? And how does that translate to me getting acknowledged and compensated? Until the language is clearer, AI is going to be very detrimental to actors, not just to the most popular actors. Regardless of where you are in your career as an actor, it’s a threat.

There was a time when you could be an actor who does a few guest-stars or co-stars per year, and you could survive off that. That’s not the case anymore. A lot of actors aren’t making enough for health care. We’re not making enough to pay rent. And I think a lot of that has to do with the residuals model — what we gave away in the last negotiation cycle. When I started in my career, the amounts I would get on basic residuals checks are not comparable to what I get now. We gave away syndication in exchange for “new media,” but new media isn’t even new anymore. Netflix can drink — it’s more than 21 years old as a company. It makes no sense that we’re acting as if we don’t understand the technology. Everyone streams. They know that they’re supplying something we want, yet they’re stingy about paying the people making them relevant.

In early spring of last year, I found out that there’s a provision in the SAG contract from 1947 saying that all actors are supposed to be paid half a day’s rate for any TV or theatrical auditions that they haven’t booked. And when I found that out, I went through a phase where I was mad, mad, mad. Because my mom had kept an audition book since I was 4 or 5. It has every audition I’ve ever been on, how well I did, and what I wore. I started thinking about it relative to this provision, and it’s safe to say that over my 30-year career, I’ve been on 1,000 auditions, which is half a million dollars (at a half-day rate of $541) that I wasn’t paid. Half a million dollars that could have been reinvested in my career, helped my mom out, paid for college or even a down payment on a house.

From a diversity standpoint, I’ve definitely been aware of when I’ve been brought to an audition as a performative option in the event that they don’t want to go to the default and have a white actress. And sometimes it’s like, “Why are you wasting my time?” Because if you’re bringing me in, it can’t just be to show that you’re doing the equitable thing. You’re going to have to pay me. At the very least, I’m getting $541 for the performance, and I can reinvest that. Time is money.

For a lot of actors, the amount of money we put into this is not sustainable. But we do it, because we love it and we’re so hopeful that any audition could be that break for us. It’s that simple. But I think the tide is turning. The last time we had negotiations was in 2020, when my friends and I were at home. Since then, we’ve had time to look at the contracts, assess what’s not going right, and stay involved.

A couple of actors and I formed an organization called auditionsarework.org in order to empower actors and teach them about the SAG pay provision. We were all on Zoom together when we got a message in the chat that the strike authorization passed with, like, 98 percent, and we all lost it. You just never know. Finally, the actor community showed up. I joke that actors think SAG is like Raya. They’re like, “I’ve got to get in. I’m on the wait list. Have you heard anything? Can you recommend me? What do I have to do?” Then once they’re in, they’re like, “Yeah, I’m in, but I don’t know why I’m here.” But it’s not just for clout. Getting involved with the union has been one of the best things I’ve done for myself in the last three years. And I think actors are starting to realize that we’ve got to pay attention to the numbers. For so long, the Writers Guild has been branded as the hard-asses who go on strike while everyone’s like, “Actors, well, I don’t know. Give them a mirror. They’ll be fine.” And we were like, “Excuse me, no.”

All I want is for actors to stop devaluing their time, to know what they’re worth. And I want producers, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, and the studios to act like we’re in this ecosystem together.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.