At the 96th Academy Awards, Oppenheimer won seven Oscars, including Best Picture.

Few films have ever been more based on a book than Oppenheimer. Christopher Nolan’s adaptation of Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography, American Prometheus, manages the astonishing feat of distilling almost every single one of the book’s 591 pages onto celluloid. Seemingly no bit of dialogue, nor stray anecdote, about the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer goes unused.

In fact, Nolan’s chief creative license comes not in the film’s content but its form. While American Prometheus is told in rough chronological order, Oppenheimer skips around the timeline thanks to a pair of nesting framing devices built around a pair of 1950s hearings. Nolan also frequently cuts to fantastical imagery that attempts to dramatize what it was like inside Oppenheimer’s head. As Matt Zoller Seitz notes in his review, this method recalls the experience of getting through a book like American Prometheus: It “paradoxically captures the mental process of reading a text and responding to it emotionally and viscerally as well as intellectually.”

Nevertheless, Oppenheimer is still a movie, which means that even this most rigorous of biopics must at times employ shortcuts and shorthand. With American Prometheus as our guide, here’s a rundown of what’s fact and what’s fiction.

Did Oppenheimer poison his Cambridge tutor’s apple?

The early scene of Oppenheimer poisoning an apple belonging to Patrick Blackett, his Cambridge tutor, is so bizarre that it seems unlikely to have been a screenwriter’s invention. Indeed, it did happen: In the fall of 1925, Oppenheimer really did inject chemicals from the school lab into Blackett’s apple. No one, not even Oppenheimer himself, seemed to know why he did this. As American Prometheus notes, “Robert liked Blackett and eagerly sought his approval.” The attempted poisoning appears to have been a case of misdirected “feelings of inadequacy and intense jealousy.” Luckily, Blackett never consumed the offending fruit, though in real life the university found out about the incident. Oppenheimer’s parents intervened to prevent him from being expelled, and the young scientist was put on probation and sentenced to mandatory psychiatric counseling.

There are disparate opinions on whether the apple was truly poisoned with cyanide, however. Noting that instead of being tried for attempted murder, Oppenheimer got off with a relatively lax punishment, Bird and Sherwin conclude it was more likely he “had laced the apple with something that merely would have made Blackett sick.”

Was Oppenheimer one of the first people to theorize about the existence of black holes?

In the film, one of Oppenheimer’s first scientific breakthroughs is his theorizing about the potential of dead stars collapsing inward with such gravity that even light could not escape — what we now know of as black holes. Oppenheimer and his student Hartland Snyder really did publish such a paper, and that paper really did come out the same day Hitler invaded Poland. But Oppenheimer the film makes a slightly bigger deal of this than Oppenheimer the man did. While brilliant, Oppenheimer’s intellectual temperament often prevented him from embracing all the possibilities of his discoveries. “Oppenheimer never took the time to develop anything so elegant as a theory of the phenomenon, leaving this achievement to others later,” American Prometheus states. “Having made the initial creative leap … [he] quickly moved on to another new topic.” A footnote adds that, when approached about the subject decades later, Robert “expressed no interest in what was rapidly becoming the hottest topic in physics.”

How tumultuous was Oppenheimer’s romance with Jean Tatlock?

As in the film, Oppenheimer met a med student named Jean Tatlock at a Communist party (with a lowercase P) hosted by his landlady. Within months, they began a romance. American Prometheus describes Tatlock as “a free-spirited woman with a hungry, poetic mind … always the one person in the room, whatever the circumstances, who remained unforgettable.” She was also an official member of the Party, though she admitted to Oppenheimer that she “found it impossible to be an ardent Communist.” It was this relationship, as much as the Depression and the Spanish Civil War, that pushed him to embrace left-wing social causes.

Although Oppenheimer’s friends later described Tatlock as his true love, their romance was as stormy as depicted in the film; the running bit about her hatred of flowers comes directly from the book. (We’ll never know whether she ever interrupted coitus to make him read from the Bhagavad Gita.) Robert Serber claimed she “disappeared for weeks, months sometimes, and then would taunt [him] mercilessly … She seemed determined to hurt him, perhaps because she knew Robert loved her so much.” However, while the film shows Oppenheimer as the one who ended their on-again, off-again relationship, American Prometheus states that “in the end, it was Tatlock who made the final break.” What this says about Nolan’s filmmaking vis-à-vis female agency, I’ll leave you to debate. However, it was not a completely clean break, and Oppenheimer really did leave Los Alamos in 1943 to spend the night with her. They never saw each other again.

How did Jean Tatlock die?

On January 4, 1944, Tatlock was found dead in her bathtub by her father. She had taken sleeping pills and left an unsigned note. Her death was ruled “suicide, motive unknown.” Bird and Sherwin agree that much of the evidence aligns with the accepted story. The night before her death, she told a friend she was feeling “very depressed,” and those close to her reported she was struggling with her sexuality. Still, the authors leave room for a seed of doubt. Noting the existence of chloral hydrate in her system, they open the possibility that Tatlock might have been “‘slipped a Mickey’ and then forcibly drowned,” quoting a doctor who says, “If you were clever and wanted to kill someone, this is the way to do it.” As a nod to the uncertainty around Tatlock’s death, Oppenheimer depicts both the official version and the conspiracy theory.

Was Kitty Oppenheimer an alcoholic?

Most of the supporting characters in Oppenheimer are sketched with only a single trait: Jean Tatlock is naked; Richard Feynman plays the bongos; Edward Teller stopped worrying and loves the bomb. Emily Blunt’s frustrated wife Kitty gets more screen time than most, but even she is defined largely by her ubiquitous martinis. American Prometheus features plenty of unflattering character witnesses for Kitty — her sister-in-law calls her “evil” — many of whom discuss her heavy drinking. However, her drinking only seems to have become a problem once Robert was ensconced in Princeton after the war. “A free-spirited, whimsical woman, Kitty found it impossible to fit into Princeton’s stiff, small-town, high-society scene,” the authors write. And what the film doesn’t spotlight is that Robert was hardly a teetotaler himself. “His martinis were strong and he drank them with pleasure,” Bird and Sherwin say, and a friend remembers parties at which “Oppie made everyone drunk quite consciously.”

Did Oppenheimer try to give away his child to a friend?

No one would award the Oppenheimers the Nobel Prize of parenting. The scene in Oppenheimer when Robert suggests giving away his son to his best friend, Haakon Chevalier, is based on a real conversation, but the circumstances were different. After the birth of daughter Katherine in 1944, Kitty went home to see her parents, taking 2-year-old Peter with her. (She likely suffered from what we today would call postpartum depression.) Baby Katherine was left with Kitty’s friend Pat Sherr; Robert visited twice a week. A few months in, Robert asked Sherr if she wanted to adopt Katherine, saying, “I can’t love her.” She declined, later telling the authors of American Prometheus that she felt Oppenheimer wanted his daughter to have “the fair deal that he felt he couldn’t give her.”

Did Chevalier really ask Oppenheimer about passing nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union?

The “Chevalier Incident” looms large in Oppenheimer’s security hearing, and the actual events played out the way they do in the film. Shortly before Oppenheimer left for Los Alamos, Chevalier casually informed him that their mutual acquaintance George Eltenton was available to pass confidential technical information to the Soviets. Oppenheimer called the proposal treason, and that was that. Whether the conversation was cut short by Kitty bursting in and saying, “The brat’s down — where’s my martini?” is unknown, as is whether Eltenton was an official Soviet spy or merely an enthusiastic amateur. (Bird and Sherwin lead toward the latter.)

Oppenheimer’s first mistake was in waiting months to disclose the conversation to security officers. His second mistake was not telling them the whole truth. He refused to name Chevalier and made up what he later called “a cock-and-bull story” about Eltenton approaching multiple people. For his postwar enemies, this was irrefutable proof that Oppenheimer could not be trusted.

Was Los Alamos uninhabited before the scientists moved in?

In addition to the Los Alamos mesa finally being a way to combine his two great loves, New Mexico and physics, the film’s Oppenheimer pitches it as the perfect tabula rasa for a secret nuclear lab: The only traces of humanity are a nearby boys’ school and the Natives who use the location as a grave site. However, there were rural communities living in the vicinity of Los Alamos as well as the Trinity test site. Early screenings of Oppenheimer have been met with protests meant to call attention to the harm the U.S. government inflicted on these “downwinders,” many of whom later developed cancer as a result of radiation exposure.

Was there 11th-hour drama before the Trinity test?

It would not be a movie if the scientists at Los Alamos did not face a last-minute obstacle before the Trinity explosion. Oppenheimer gives us two: a late-night storm and a failed implosion test. Both really happened. The night before the test was marked by “thirty-mile-an-hour winds and severe thunderstorms,” raising the agonizing possibility that Trinity would have to be delayed. Unlike in the film, Oppenheimer was not the only voice assuring everyone the storm would pass; the Army’s meteorologist agreed. During the event, the test was delayed but only by 90 minutes, from 4 to 5:30 a.m.

The drama over the failed implosion test was less intense. The previous day, the team had pinpointed the culprit: blown circuits in the test’s wiring. The actual “gadget” would be fine.

Were the scientists worried they might accidentally ignite the Earth’s atmosphere?

The film features a dark running joke in which the scientists reassure themselves that the possibility of the bomb igniting the atmosphere and thereby destroying all life on Earth is “near zero.” This comes from a real fear, first raised by Teller, of an unstoppable chain reaction sparking nitrogen in the atmosphere. In real life, Oppenheimer sought reassurance not from Albert Einstein but MIT’s Karl T. Compton, who later wrote, “Better to accept the slavery of the Nazis than to run a chance of drawing the final curtain on mankind.”

As in the film, Hans Bethe was the one who made the calculations to produce the “near zero” figure. But there was still enough suspense on the eve of the Trinity test that Enrico Fermi really did take side bets beforehand on the possibility of a nuclear apocalypse.

How complicit was Oppenheimer in the decision to target Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

Oppenheimer features a chilling scene of the United States’ top military and scientific minds discussing how and where to drop the atomic bomb. While he was sympathetic to Niels Bohr’s argument that the threat of the bomb should usher in an age of openness and cooperation, in practice Oppenheimer took the side of military brass, rationalizing that it was not scientists’ responsibility to decide how the weapon should be used. He refused to support Leo Szilard’s attempts to block the bomb from being dropped on Japan, and in the pivotal meeting, he silently gave his blessing to the decision to target Japanese civilians. Oppenheimer “played an ambiguous role in this critical discussion,” Bird and Sherwin write. “He had won nothing and acquiesced to everything.”

Much of this scene is taken directly from the official record of the meeting. However, the moment when Kyoto is removed from the list of targets because the secretary of State honeymooned there was a last-minute addition to the script, inspired by actor James Remar’s own research into his character. “It has this bureaucratic quality of a group of men discussing massive destruction and how they’re going to do these awful things. And you’re suddenly seeing a human face to these negotiations,” Nolan told Vulture.

Did Oppenheimer tell Harry Truman he felt he had blood on his hands?

Oppenheimer’s infamous meeting with Truman took place in October 1945. It did not go well: Oppenheimer failed to convince the president of the need for international control of atomic energy, while Truman confidently stated the Soviets would never get the bomb. Getting nowhere, Oppenheimer really did confess his guilt over the Manhattan Project, which turned Truman’s stomach. His quip in the film “Don’t bring that crybaby into my office again” is inspired by real remarks Truman made afterward, as is Oppenheimer’s line about giving Los Alamos back to the Indians.

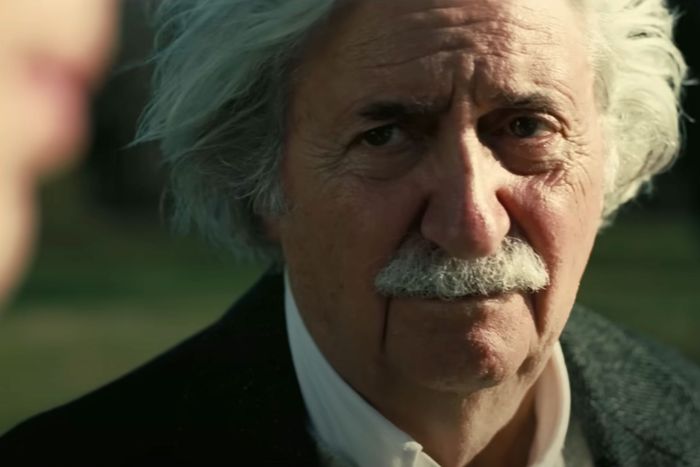

What was Oppenheimer’s relationship with Albert Einstein like?

Tom Conti’s Einstein functions as the moral center of Oppenheimer, popping up every so often to provide words of wisdom. The film’s portrait of Einstein and Oppenheimer’s relationship is largely accurate. Scientifically, they were at odds: Einstein never got onboard with the quantum revolution, leading Oppenheimer to consider him a relic of an earlier age. Thus American Prometheus calls their relationship “always tentative,” though Einstein “eventually acquired a grudging respect for” the younger scientist. The specific interactions seen in Oppenheimer never happened, though the pivotal 1947 meeting that recurs throughout the film seems to refer to a real birthday celebration — which included a commemorative book full of backhanded compliments — that the Institute for Advanced Study threw for Einstein in 1949.

Was Klaus Fuchs the reason the Soviets got the bomb?

Klaus Fuchs was a German Communist who fled the Nazis and settled in England, where he became an acclaimed theoretical physicist and, thenceforth, a Soviet spy. (Funnily enough, actor Christopher Denham also played a spy at Los Alamos in the show Manhattan.) As a member of the British contingent, he “passed detailed written information to the Soviets about the problems and advantages of the implosion-type bomb design.” When Fuchs’s espionage came to light in 1950, Oppenheimer’s enemies naturally blamed the lab’s director and “demanded renewed scrutiny of Oppenheimer’s left-wing past.”

While the most famous, Fuchs was not the only spy at Los Alamos. A technician named Ted Hall, who feared a U.S. nuclear monopoly, passed detailed reports on the lab’s workings to the Soviets. As American Prometheus states, “Hall was the perfect ‘walk-in’ spy; he knew what the Russians needed to know about the atomic bomb project; he needed nothing himself and expected nothing.” A technician named David Greenglass, the brother of Ethel Rosenberg, also passed secrets to the Soviets, which ended poorly for the whole family. Historians recently uncovered a fourth spy, engineer Oscar Seborer, who might have been the most important of them all. According to the New York Times, “His knowledge most likely surpassed that of the three previously known Soviet spies.”

Why did Lewis Strauss hate Oppenheimer?

After hiring Oppenheimer to run the Institute for Advanced Study, why did Lewis “It’s Pronounced Straws” Strauss devote years of his life to ruining the man? American Prometheus notes that, while the men were initially cordial to each other in Princeton, “the seeds of a terrible feud were born.” (Oppenheimer was not wholly innocent; at one point, he prevented Strauss from buying a house nearby by having the institute purchase it instead.) As the film depicts, Oppenheimer really did humiliate Strauss in front of Congress when the two men disagreed about exporting radioisotopes, a scene that is taken largely verbatim from the book. Afterward, the authors write, “Strauss was angry, and he would stay angry until he had settled the score … Oppenheimer had made for himself a dangerous enemy who was powerful and influential in every field of Robert’s professional life.”

Still, while Strauss’s feud with Oppenheimer was in many ways a petty power struggle, the men did have a very real disagreement about the hydrogen bomb. Strauss convinced himself that Oppenheimer was “sabotaging the project” and had paranoid visions of the doctor poisoning the scientific community against him. The film condenses the years of debate over the H-bomb, but the broad strokes are accurate, as are beats like Oppenheimer snubbing Strauss’s son and daughter-in-law at Strauss’s birthday party.

Who gave Oppenheimer’s security file to William Borden?

A WWII veteran obsessed with the Soviet nuclear threat, William Borden in the early ’50s became the favorite attack dog of Oppenheimer’s enemies. Oppenheimer treats the question of who provided him Oppenheimer’s security file as a big mystery, but if you’ve read American Prometheus, you’ll know the answer from the start: It was Strauss! (The film skips over the fact that H-bomb enthusiast Teller played an equal role in setting Borden against Oppenheimer, whispering in Borden’s ear about delays in the thermonuclear program and Kitty’s previous marriage to a Communist.) The book includes a pivotal meeting in April 1953, in which Borden and Strauss seemingly agreed “Borden would do the dirty work and Strauss would provide him access to the information he needed.” After examining the record of withdrawals of the file, the authors conclude the sequence “was surely coordinated; it could not have been a coincidence.”

Was David Hill’s testimony the thing that turned the Senate against Strauss?

The framing device around Strauss’s Commerce-secretary confirmation hearings is Nolan’s one major departure from American Prometheus, which devotes less than a page to Strauss’s comeuppance. While it’s true that a Manhattan Project scientist named David Hill, portrayed in the film by Rami Malek as a kind of Chekhov’s Eyeball, testified about Strauss’s obsession with destroying Oppenheimer, he was far from the only witness to provide negative testimony. As Slashfilm notes, Los Alamos scientist David Inglis had previously delivered his own scathing words about Strauss’s “personal vindictiveness.”

Furthermore, the scientists weren’t the only ones against him. Like Oppenheimer, Strauss also had made a powerful enemy: New Mexico senator Clinton Anderson. A contemporary report from Time called the confirmation battle the inevitable result of the “blood feud” between Strauss and Anderson, which “has gone far beyond the personal quarrel between two men; it has widened out to involve their friends and their associates, strained old ties and old loyalties, brought charge and countercharge, insult and counterinsult, rumor and counterrumor.” Rather than a stirring congressional speech, it was intense backroom lobbying from Anderson that truly doomed Strauss’s confirmation. But the bit about John F. Kennedy voting against him is real.

More on Oppenheimer

- Every Oscar Best Picture Winner, Ranked

- Ryan Gosling and Emily Blunt Break Up with Barbenheimer on SNL

- Fallout Is Barbenheimer: The TV Show