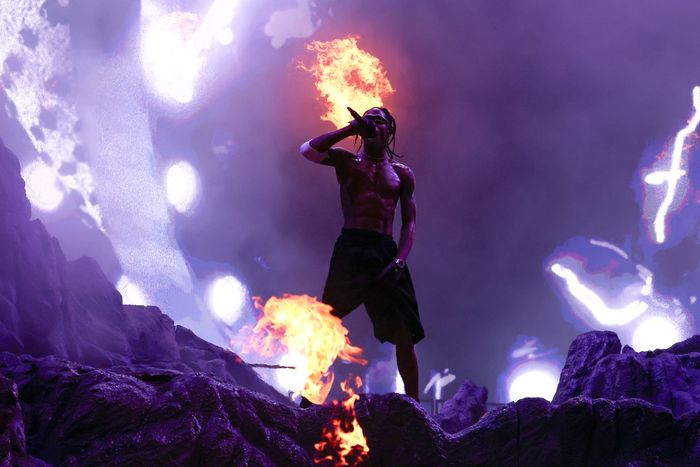

Travis Scott is a salesman, a purveyor of sought-after T-shirts, Jordans, Chicken McNugget body pillows, albums, and concert tickets. His career is a convergence of long-simmering trends in rap: the proliferation of pharmaceutical drugs, the mainstreaming of streetwear, the embrace of the mosh pit, the obsession with marketing. Scott has synthesized a decade of developments in pop, trap, R&B, art, and fashion into a sturdy catalogue of hits and smart corporate collaborations that account for shifts in taste the way architects plan around some degree of sway. He has always painted himself as a hedonist, someone who can meet the audience wherever it’s gathering. That impulse has primed him perfectly for an era of denial and decay. But the tragedy at his Astroworld Festival in 2021 — in which ten concertgoers, including three under the age of 18, died as a result of a crowd crush — punctured the illusion of freedom, upending the notion that it’s possible to both court and contain chaos.

Scott didn’t seem prepared for any of it — no one should have to be. His flustered response turned into defensive posturing as civil and criminal cases progressed. In June, a Texas grand jury declined to indict him, but he probably won’t have much to say about it anytime soon with everyone still under a gag order and civil suits against Live Nation in play. This is a precarious time for his fourth album, Utopia, to land. Returning to the task of making motivational music without addressing the devastation at the end of the last rollout seems gauche, and the sensitivity it would take to shake the air of unfinished business is not endemic to this catalogue. So Utopia and its accompanying film, Circus Maximus — which Scott wrote and directed with help from Nicolas Winding Refn, Gaspar Noé, Valdimar Jóhannsson, Harmony Korine, and Kahlil Joseph — come barreling back to the party shaken but louder than ever, like a friend who just booted and rallied.

Utopia is a 19-song expanse of wild nights interspersed with moments of nondescript gloom, and Circus Maximus is a literal and metaphysical trip through 12 of the album’s songs, first in a series of globe-trotting music videos and then in a live performance that takes hairpin turns through genres like its soundtrack. It makes the case for the album being overloaded but also repeats a handful of songs at the expense of getting deeper into Utopia. Scott’s vision for a perfect world isn’t expressed very clearly. You come away with a more refined picture of the artist’s tastes, but you don’t get that much closer to understanding what makes him tick, outside of a collector’s mind-set — he knows how to make works for mass consumption that retain an air of scarcity. (His Fortnite icon is difficult to come by in part because it was only available for a week. His merch is an easy flip; his kicks almost never sit. His film wasn’t easy to get into on opening night; there were commemorative shirts if you did. You can buy a replica of the Utopia briefcase that was handcuffed to Travis’s bodyguard.)

Utopia and Circus are both flashy endeavors packed with celebrity turns and steamy threesomes and flights on lavish jets and gigs at the Amphitheatre of Pompeii, where Scott’s performance was among a handful of such events in over 50 years. Pink Floyd played songs from its early albums in 1972’s Live at Pompeii film. Like Ye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, Scott’s latest uses progressive and classic rock to signify opulence and otherworldliness: “Hyaena” opens with a bit of British band Gentle Giant’s 1974 album, The Power and the Glory; “Sirens” flips the title track from Boston quartet New England’s Explorer Suite. (Like the 2021 stadium spectacles where Ye unveiled Donda, the Pompeii performance descends into a warlike scene distorted by copious smoke. It’s a curious choice to film at that location and obscure it with stacks of speakers and disorienting lights.) Scott had even tried to plan a show at the Giza pyramids, pining for the majesty of the Grateful Dead’s Rocking the Cradle: Egypt 1978. A sample from Todd Rundgren’s Utopia feels curiously absent here.

Scott wants to both showcase a wider sonic and emotional palette and appease the ragers. Though the flows are manicured and melodic, the bars stumble over the album’s cross-purposes. “Skitzo” sinks while trying to get deep: “Seen the top 10 pen list / I don’t even know how they could pen this / Knowin’ that I’m the human Pinterest / Need true love, but I know true love’s like a friendship / But even Titanic had an endin’ / I rock the boat with ice so expensive.” “Modern Jam” complains about being unable to tour — “Know it’s been a year since I seen the road / Had me inside like I’m on parole / I’m outside like I’m on patrol / I hear the zeitgeist, now I’m in the zone” — without tapping into the gravity of why, which is a shame, since some of the most intriguing moments in Travis’s audiovisual presentation happen when he stops flexing and offers a glimpse into the determination under the hood. “My Eyes,” with gorgeous vocals from Sampha and Justin Vernon, picks up the pace in the middle as the beat changes, and Scott pivots from toying with melody and tricky, stuttering flows like Frank Ocean — “Three time to get me T-T-T’d / Still same phone, AT&T-T” — to a ferocious verse where he lays out what’s at stake for him with unnerving honesty: “I replay them nights, and right by my side, all I see is a sea of people that ride wit’ me / If they just knew what Scotty would do to jump off the stage and save him a child / The things I created became the most weighted, I gotta find balance and keep me inspired.” But that kind of candor comes and goes. This guy would much rather be rapping about something expensive.

Utopia is most effective as a survey of 15 years of trends in stadium rap, a sound steeped in the bombast of Ye records. The Chicago rapper and producer, whom Scott began collaborating with on Cruel Summer and Yeezus, is the album’s North Star. One wonders if Ye’s unique position — less than a year removed from a courtship of white-supremacist and antisemitic figureheads — is the only reason we never hear his voice. The sanitized religious trap of Donda surfaces on Utopia’s “Thank God,” “God’s Country,” and “Telekinesis,” songs originally intended for Ye that credit him as a co-writer or producer; it’s no use letting the few faith-based bars in your catalogue go to waste as long as you’re fighting devil-worship allegations. “Modern Jam” sports a beat crafted with Daft Punk’s Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo that seems to have appeared on an early version of “I Am a God.” Scott even uses the older song’s flow. “Circus Maximus” with the Weeknd is a dead ringer for “Black Skinhead”: “A walkin’ distraction / I’m naturally Black and / Unnaturally breathin’/ Like a waist that is snatchin’.”

It would be reductive to call Utopia a Yeezus rehash, though. There’s just as much Drake, 21 Savage, Thug, Future, Lil Uzi Vert, and Playboi Carti peppered into the mix. Really, the story is that Travis Scott is a slippery and savvy enough aesthete to never be counted out, a student of the charts able to occupy whatever form the hit parade demands. Cooing through Auto-Tune over the reggaeton groove of the single “K-Pop,” Scott holds court with Bad Bunny while sneaking in a reference to ketamine. “Delresto (Echoes)” with Beyoncé offers Utopia a bit of dance-floor dynamite from the singer’s sequined Renaissance era. “Fe!n” taps into the 8-bit menace of Playboi Carti’s Whole Lotta Red; “Topia Twins” and “Til Further Notice” benefit from 21’s deadpanned threats. At one point, you hear Travis’s take on a Detroit flow. Elsewhere, he trades verses with Westside Gunn over an Alchemist beat. In the film, Sheck Wes pushes Scott’s lyricism in a performance of Fein, which also features Playboi Carti. (The number of men accused of abuse who make appearances on the album mirrors Donda’s attempts at rehabilitating Marilyn Manson.) There’s drama in the guest list, which doesn’t seem to faze Scott: In “Meltdown,” a whispering, vindictive Drake fires shots at Pusha T and boasts about destroying classic jewelry that belonged to Pharrell, who co-wrote Utopia’s “Looove” with Kid Cudi, who’s not on speaking terms with Ye, who had it out with Drake and Travis in the Astroworld era over the strays he caught in “Sicko Mode.”

This project serves two masters: Travis needs to deliver the demon raps and psychedelic narratives that his following has come to expect, but he also must have you know that he’s not really this person and that the past two years have presented him with challenges. While the rage comes naturally to Scott, the reflection can feel feigned and forced. His discography is a snow globe where the party never ends, and he’s not trying to break it. The sense that nothing can derail the quest for the idyllic night out sits at the core of Scott’s art — not beef, not death, not taxes. Too much money is tied up in this endeavor for it to do anything other than expand. Scott is the ideal vessel for all of this but not for the graceful continuation of life that this album could have been and that brief moments of reflection throughout Utopia and Circus Maximus reveal to be possible. Both Utopia and the film are much more interested in fast cars, hot sex, and quality drugs, and that’s par for the course for someone who inspired a generation to scream, “It’s lit!” Switch up the product, and your customers might cop from someone else.

Correction: An earlier version incorrectly listed when Ye’s Donda stadium shows were held, as well as the years Pink Floyd’s Live at Pompeii and Gentle Giant’s The Power and the Glory were released.