This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

When it’s 90 degrees at 6 p.m., flannel shirts wrapped around jean-shorted waists are so foolishly optimistic, so delusional, they circle back around to almost tragic. But everyone’s wearing them, including myself (how do you do, fellow teens?) in rugged, muted blues and greens; flannel is back, but my friend Sophie points out the punky red-and-black check of our ill-advised hipster youth is decidedly out. The sad, sweat-soaked flannel is the first thing I clock when I walk through the sunny open field turned parking lot to the BankNH Pavilion in Gilford, New Hampshire, where Gen Z’s New England royalty, Noah Kahan, is playing his first of two sold-out headline shows for a crowd of 9,000 a pop amid an early-September heat wave. That number may be a drop in the bucket compared to his 1.5 million followers on TikTok, but Kahan is a long way from where he was last year, playing for audiences of a couple hundred at small festivals. And his pop-inflected folk hits different in front of Northeasterners.

Kahan grew up nearby, between Hanover, New Hampshire, and Strafford, Vermont. This summer, Kahan exploded, thanks to a reissue of his breakout third album, 2022’s Stick Season, featuring seven new songs, that landed him at No. 3 on “The Billboard 200.” After topping the rock and alternative charts, he finally hit “The Hot 100,” peaking at No. 25 in August for “Dial Drunk,” his rollicking, banjo-fueled single featuring Post Malone, which he teased on TikTok with the chef’s-kiss word-play “I dial drunk, I’ll die a drunk, I’d die for you!” This month, he was featured on new country star Zach Bryan’s latest EP, and next summer, Kahan will cap-off a huge North American stadium tour with two nights playing New England’s most consecrated ground, Fenway Park. His album’s namesake single, Stick Season, refers to “the time of year in Vermont, ‘stick season,’ when all the leaves are off the trees,” he told the lyrics site Genius in January. “It’s a term that was used by some of the older folks in the town I grew up in to describe this really miserable time of year when it’s just kind of gray and cold, and there’s no snow yet, and the beauty of the foliage is done.”

It’s an apt description for all of his music: Kahan sings from a perspective situated inside a childhood bedroom or from a passenger seat, staring out the windows onto familiar landscapes at the bleakest and most desolate times of the year, metaphors for sensitive-suburban-boy ennui. His fans say they like him for one of two reasons: his openness about mental health (he sings and posts extensively about depression and positive experiences with therapy) and the way his music captures what it’s like to grow up in this region, an underexamined point of view versus the mythologized teendoms of, say, California or Texas.

“Like, he talks about the certain feelings that you get from our seasons, like in ‘Homesick,’ about how it’s always cloudy and it feels isolating,” Delaney, a teen in clear-rimmed glasses tells me while playing cornhole with her mom on the lawn outside the venue. The two drove up from Boston. “That’s why I like that song a lot. Because I know what that is. I’ve been through that.” Clouds can be so deep when you’re 16.

There are tons of mothers and daughters here, younger teens in need of rides and supervision, and women in their early 20s whose own personal-favorite coming-of-age New England media is almost certainly Gilmore Girls. There are straight couples, too; blonde women and softboys who get it; a boyfriend with a Nalgene carabinered to his cargo shorts and a T-shirt that reads corgzilla with a corgi on it who walks by another boyfriend in a shirt that reads poodle dad. And: mohawk-mullet boyfriend. American-flag-print Vineyard Vines–whale boyfriend. Matching-tour-shirts glasses boyfriend. There are also lots of lesbian couples and BFF duos holding hands.

Beyond flannel girls and doggo-tee boys, the Kahan phenomenon feels like a revival of a moment that went away (or so we thought) only around a decade or so ago: “Stomp and Holler,” the semi-posthumous name given by Spotify to a genre that peaked between 2010 and 2013, defined by acts like Mumford & Sons, the Lumineers, the Avett Brothers, Of Monsters and Men, and Hozier. A time when the alt charts were taken over by the Country Bear Jamboree. This is “Ho Hey” music, folkish adult contemporary and rock featuring very strummy guitars, banjos, mandolins, or ukes; big rousing kick-drum and stomp-clap arena-ready refrains; and coal-miner-cosplay aesthetics. Like a bare Edison bulb at a nouveau taco joint, all of these stylistic decisions were meant to project “authenticity,” but by trying so intentionally, and by ignoring the aesthetic realities of the time (namely the explosion of social media), they came off as forced and fake. None of this is a judgment of the actual quality of the music. As in any genre, there were good and bad actors, and people can be deeply moved by either. It’s just to say that, in the Gen-Z (and Gen-Alpha?) retro nostalgia cycle, a phenomenon that might still seem recent enough to be uncool to the olds is already coming back around like Y2K and indie sleaze before it.

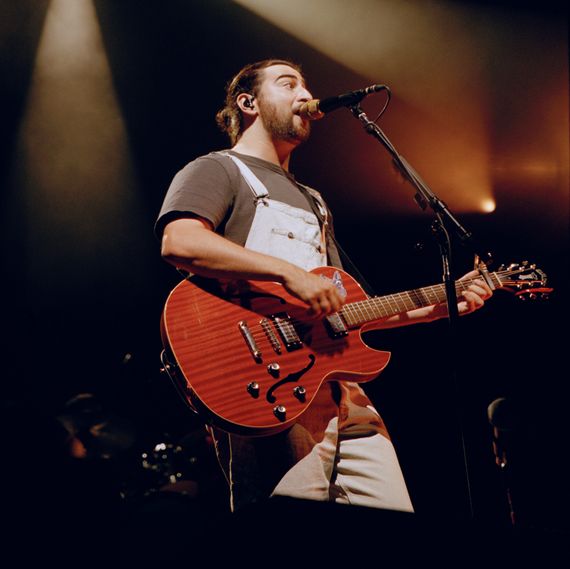

Kahan’s got the stompable, soaring choruses and acoustic-folk riffs — not to mention the beard and the man bun — but he evades Old Stomp and Holler’s authenticity issue by eschewing stylized Americana imagery for real, relatable, personal lyrics about house parties and people moving away to college. When he sings, “The intersection got a Target / And they’re calling it ‘downtown’” on “New Perspective,” that’s social realism, baby.

More than Vermont or New Hampshire, his music really lives, spiritually, on TikTok. In October 2020, he uploaded a video to the platform in which he sings a throwaway verse, a catchy acoustic ditty hashtagged “#depressedjasonmraz #prozackeanureeves.” It ends: “I’m terrified of weather ‘cus I see you when it rains / Doc told me to travel but there’s COVID on the planes / I’m fucked/I’m fucked/and I suck. You suck. And this sucks. Fuck…” Both the video and song went viral, so he took out the F-bombs and replaced them with a chorus, which went on to become “Stick Season.” He’s constantly interfacing with fans, making self-deprecating jokes, trying out new stuff for them, or duetting with their covers. Outside the venue, I see two girls with flat-ironed hair, snacking in the shade of a giant inflatable Jäger bottle, in custom T-shirts featuring tweets of Kahan’s: one says “Daddy likey,” another says “Daddy is a corporate sellout.” They each tell the other that they should tweet their shirt at him.

I start chatting with 20-year-old UNH English major Emma and her 18-year-old friend Hailey. They belong to a segment of Kahan’s fan base that self-identifies as “long-distance daughters” who post TikToks of themselves, sometimes crying or freshly post-cry, with captions about all of their big feelings — guilt, heartbreak, loss, wistfulness, nervousness — concerning moving away from their hometowns and families. They plan on getting matching tattoos of the Kahan lyric “I do not exist to die.” It’s the introspective, emo alternative to RushTok with millions of girls narrating their first summers away from home as if they’re each starring in their own coming-of-age Sundance feature. (One thing that hasn’t changed since the first Stomp and Holler wave is that it attracts the whitest crowd imaginable.) They resonate with the way Kahan sings about that transitional period in one’s life. They post these sobbing selfie videos to the chorus of his song, “You’re Gonna Go Far,” which is sung from the perspective of the people who stay behind (“We ain’t angry at you, love / You’re the greatest thing we lost … And we’ll all be here forever”). Connor, a 22-year-old in town from Maine for Noah Night Two, puts it this way: “He talks about small big problems.” It’s music to be a main character to.

Inside the venue, I buy a can of Noah Kahan’s Northern Attitude IPA (yes, he has his own IPA collab) to bring to my seat for a full 4-D experience. It’s the right choice: Kahan opens with his song “Northern Attitude,” one of his liveliest Mumfordian tracks: “If I get too close / And I’m not how you hoped / Forgive my northern attitude / Oh, I was raised out in the cold.” My friend, who is from the U.K. and grew up going to punk shows as a teen, tells me this is the single loudest crowd she’s ever heard. A couple of girls hold signs up toward the front of the pit. One is sort of a giant, bedazzled version of his driver’s license that says “Daddy” where his name should be. Another says “THIS SEXY JEW GOES TO THERAPY.” A disgruntled, pink-faced dad, here with his wife, queer-presenting adult kid, and kid’s queer-presenting adult girlfriend, screams over the guitars: “Put your sign down!” All of the boyfriends standing with their arms crossed are singing along to every word.

Kahan introduces himself to the crowd as “Jewy Tomlinson” and “Jewish Capaldi,” before launching into the simple folk-groove of “She Calls Me Back” (Kahan is a nice Jewish boy; the song begins, “There was heaven in your eyes / I was not baptized”). When Kahan performs, his eyes get wide and he darts them side to side in close-up on the big screens. His tenor is polished and mercifully much less cursive in person, especially shining on all the mmms and ohhhs peppering his songs. He prefaces a song that more directly addresses mental health, “Growing Sideways,” by saying, “When I was a kid, I was depressed. I’m still depressed, but I was depressed-er. I don’t know what was wrong with me. I spent hours playing Club Penguin and watching NBA dunk compilations.” He doesn’t entirely mean it as a joke, and the audience doesn’t entirely take it as one, cheering their support, cheering for feeling seen. He adds, “I know I look like I’ve been through a grizzly divorce and custody battle, but I’m only 26.” You quickly understand that Kahan is never self-serious — an emotional and sensitive songwriter, yes, but with the goofy energy of a friend’s nonthreatening elder brother who has more depth than he lets on.

At one point in his show, Kahan takes a moment to shout-out everyone who came alone. “I literally go to fucking hibachi by myself,” he says. “Everyone feels sad for me. I tell them it’s my birthday; they throw a whole zucchini in my mouth.” It’s a testament to the way he manages the tone of the show that he can say all that and then, one song later, I have goose bumps and catch myself crying.

The Stomp and Holler revival feels real — even if no one’s calling it that anymore — especially hearing people go wild for a mandolin solo. There are two teen girls to my right in two separate rows, one in front of the other, both here with their parents. As they sing along, they sob and hold their hands to their hearts, feeling everything and looking so devastated. They both film themselves while they do it, turning their cameras around to selfie mode to capture the single most overwhelming experience of their young lives.