Every year, Vulture hitches a ride through Venetian canals and ventures up into the Great White North to scout out the movies we’ll all be talking about for months to come. The red carpets at this year’s Venice and Toronto International Film Festivals may have been quieter than in previous years, due to the ongoing WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes, but the films themselves did not disappoint. Both festivals brought bounties of soon-to-be awards contenders, star-making performances, and must-see masterpieces from filmmakers around the world. Here are the ones that left us gushing.

Poor Things

Emma Stone makes a case for herself as her generation’s best actress in Poor Things, her latest collaboration with Yorgos Lanthimos. In this funny, sexy, and surprisingly moving film, which unfolds like a sort of feminist Frankenstein, Stone is Bella Baxter, a reanimated Victorian woman whose uncanny brain development allows her to sidestep all manner of sociological bullshit. She lives her life on her own terms because she doesn’t know any other way, and what a life it is — boning a caddish lawyer (Mark Ruffalo) across Europe, ditching him in Paris to become a socialist prostitute (“We are our own means of production,” she says coolly), studying human anatomy and literature, making friends with eccentrics the world over, all while coming to terms with her unorthodox development and complicated creator (a wonderful Willem Dafoe). Lanthimos’s Gothic fairy-tale, Candyland-meets-Oz-meets–Tim Burton sets and visuals are the cherry on top of this beautifully told, wonderfully bizarre coming-of-age tale. This was my favorite movie at Venice, and I can’t wait to watch it again when it hits theaters in December. —Rachel Handler

Origin

Ava DuVernay’s Origin is both essay film and melodrama, though neither description quite does it justice. The director takes Isabel Wilkerson’s influential nonfiction best seller Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents — a sweeping analysis of discrimination that finds the connections among American racism, the Nazi persecution of Jews, and India’s caste system — and attempts to translate it into the vernacular of narrative cinema. She presents Wilkerson herself (played by Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) as the protagonist of this drama and portrays the author’s very personal journey as she’s pulled into this subject, even as her life is falling apart. But she also rifles through history to present case studies from Wilkerson’s research, sometimes through extended sequences, sometimes through mere flashes. So we see tales of forbidden love in Nazi Germany, the devastation of the Jim Crow South, the treatment of the Dalits in India, and a lot more, as Wilkerson (and DuVernay) explores the mystery of social hierarchies and how they teach us to hate one another. The results are incredibly ambitious and, frankly, devastating. —Bilge Ebiri

Priscilla

Sofia Coppola’s eighth feature sticks to her favorite subject: young girls caught in a lush patriarchal web. This time, it’s Priscilla Presley, née Beaulieu, a 14-year-old girl who’s drawn into Elvis’s world in 1960s Germany, where he and her father are both temporarily stationed in the army, and where he quickly seduces her. Based on Presley’s 1985 memoir Elvis and Me, the movie is told entirely from her vantage point, which means we get an entirely new — and consistently disturbing — look at Elvis and their marriage, which begins lovingly enough but ends in emotional abuse, manipulation, isolation, and betrayal. Cailee Spaeny is naturalistic and convincingly lost as Priscilla, a dreamy loner with a killer cat-eye who’s desperate for connection and who, later, slowly awakens to the reality of her life. And Elordi is just as good as the equally astray Elvis, showing a more intimate, shadier side of him than Austin Butler did last year. —R.H.

Ferrari

Michael Mann’s rip-roaring Ferrari takes place over a few pivotal months in 1957, a key year in the life and career of Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver). The business is drowning in debt and his bankers are recommending he sell to an automotive giant like Ford or Fiat. Ferrari cars have stumbled on the race track. His local rival, Maserati, is setting new records. Perhaps more importantly, Enzo and his wife, Laura (Penelope Cruz), have just lost a son and he’s keeping the child he had with another woman a secret. The film has a circular structure, evoking the sense that time has stood still in the Ferrari headquarters in Modena. Enzo and Laura are trapped in an almost medieval world of grief and stasis, and both Driver and Cruz are spectacular and heartbreaking. Mann’s film is elegant and restless, with a sense throughout that something horrific might be lurking around each corner. But when the director straps his cameras on those cars and sends them on their way, the picture transforms into something more visceral and chaotic, a fever dream (or maybe a nightmare) of speed and smoke. —B.E.

Green Border

Agnieszka Holland’s Green Border is an urgent masterpiece, one of the more riveting and profoundly upsetting movies I’ve ever seen. Shot in black-and-white and unfolding like both a docudrama and a taut, harrowing thriller, the film follows several different characters caught in the abject horror of the current-day refugee crisis at the border of Poland and Belarus. One thread follows a Syrian couple (Dalia Naous and Jalal Altawil) fleeing ISIS with their children and father-in-law and an Afghan refugee (Behi Djanati Atai) they meet along the way. All of them are tricked into believing they’ll be able to enter the E.U. easily by plane but are met with horrible violence at the hands of the border guards, quite literally tossed back and forth over the barbed wire between the countries. Another thread follows Jan (Tomasz Włosok), a Polish border guard who’s “just following orders” until his pregnant wife (Malwina Buss) sees a video of him beating back the “tourists” (as the guards call the refugees) at the fence. Yet another tells the story of Julia (Maja Ostaszewska), a therapist who finds herself compelled to join a local activist group run by two sisters (Monika Frajczyk and Jasmina Polak), putting their own lives at risk to help the refugees with legal advice and first aid. That Holland manages to tell all of these stories in a way that’s believable, devastatingly unflinching, and narratively compelling all at once is nothing short of miraculous. —R.H.

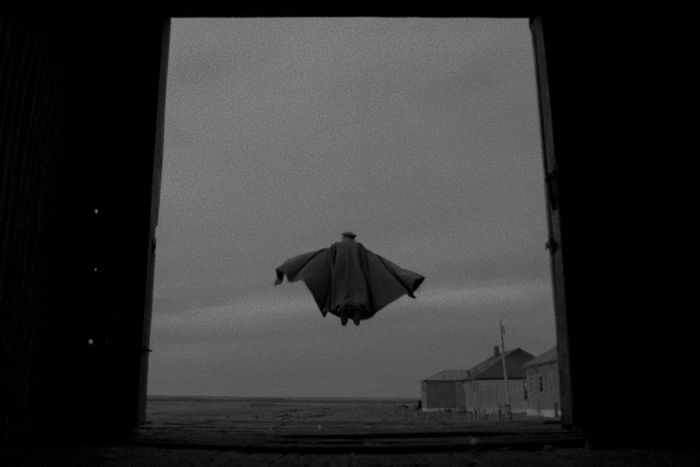

El Conde

In Pablo Larraín’s mesmerizing, stomach-turning tragicomic melodrama-horror movie, the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet never actually died. He was an immortal vampire and faked his death so that he could avoid prosecution and live out his life in peace on a remote ranch, subsisting on nutritious smoothies made of human hearts and sitting on the vast fortune he amassed during his reign of terror. That’s not even the craziest element in Larraín’s movie, which might be the most perverse project Netflix has ever signed off on. Once a bloodthirsty French ruffian who fled after the revolution with Marie Antoinette’s head in tow, Pinochet is now ancient and doddering, but he still longs for the fresh, rich necks of the young. Larraín thus suggests a kind of law of the conservation of evil: Like matter, it’s never really destroyed. It transforms and transmogrifies. As El Conde proceeds, we understand just how much the director has committed to this idea — the film has a couple of late twists that send both its narrative and its politics in delightfully bonkers directions. It’s wild to think this is now on Netflix all over the world. —B.E.

The Beast

Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast is a techno-thriller, speculative sci-fi, and romantic period drama all in one, as well as a showcase for the major talent of Léa Seydoux. Based on the Henry James novella The Beast in the Jungle, the movie follows Seydoux as Gabrielle, a woman who’s lived multiple lives and, in the near future, is engaged in a “DNA-purification ritual” that sees her revisiting many of them so that she might delete her trauma and join the AI-dominated workforce. Across 1913 Paris, 2014 Los Angeles, and 2044 Paris, Gabrielle is haunted by recurring imagery — pigeons, fortune tellers, dolls, Madame Butterfly — as well as a deep sense of impending doom, the vague idea that something awful is going to happen to her. She’s also accompanied in each era by Louis (George MacKay), her soulmate, whom she can never quite seem to work it out with. The movie isn’t so much linear as it is circular, returning again and again to Gabrielle’s fear and lust and its central motifs and themes. It’s a tense, riveting ride. —R.H.

The Promised Land

Mads Mikkelsen is uniquely well-suited for the role of Captain Ludvig Kahlen, an impoverished Danish war veteran who sets out in the mid-18th century to try and tame the Jutland Heath, a huge and forbidding area where no crop can grow and where lawlessness reigns. He has nothing in this world, but he aspires to nobility and status and can be a heartless taskmaster. But when he runs afoul of a preening and sadistic local aristocrat named Frederik de Schinkel (Simon Bennebjerg), Kahlen finally sees a repulsive, real-life version of the privilege he seeks for himself. This is where The Promised Land transforms from a stately and lyrical tale of rural survival to something more primal and intense; think Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven crossed with Michael Caton-Jones’s Rob Roy, only with more scenes of people being boiled alive. —B.E.

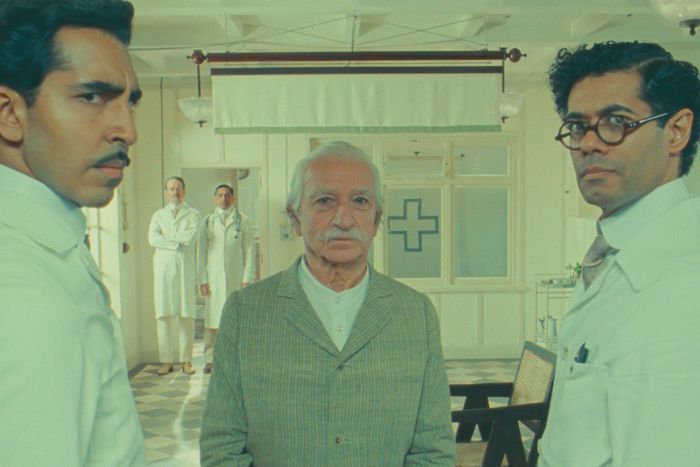

The Wonderful World of Henry Sugar

Wes Anderson’s 39-minute short at times it feels like a feature in miniature. Indeed, that might be part of the joke; the accelerated tempo of the film is the source of some of its charm, but it also presents a spiritual context for a story about the transcendent power of focus. It has Roald Dahl (Ralph Fiennes) introducing the tale of wealthy, 41-year-old gambler and hedonist Henry Sugar (Benedict Cumberbatch), who in turn finds the story of Dr. Chatterjee (Dev Patel), who then recounts the tale of Imdad Khan (Ben Kingsley), a circus performer who could see without using his eyes. The nesting-doll structure eventually makes its way back to Henry Sugar, who immediately sees the gambling possibilities of such a power and sets out to master the ways of the Indian yogi who taught Imdad Khan, learning to focus his mind on one thing at a time and eventually gaining the power to see through objects. But this knowledge ultimately transforms him, so that the prospect of making money gambling loses its appeal. It’s a typically Andersonian tale of how precociousness can be a dead end. Many of his best films are about the limits of knowledge. But here, hitting those limits allows the protagonist to forge a new path, lending this movie a quaint, almost naïve optimism. —B.E.

La Chimera

For those downtrodden journalists who didn’t make it to the Croisette, TIFF helpfully schedules press screenings of all the Cannes titles in attendance on the morning of the first day. I saw a bunch of them back to back: first the Palme d’Or winner Anatomy of a Fall, then the ultra-grim Zone of Interest. (The short turnaround time between them created a hilarious bit of gamesmanship in the Anatomy screening, as viewers took to guessing which shot would be the movie’s last.)

Both were as great as I’d expected, but it was the third Cannes film I saw that day that really took me by surprise. It was La Chimera by Alice Rohrwacher, the Italian filmmaker behind Happy As Lazzaro and last year’s Oscar-nominated short Le pupille. The movie follows a band of grave robbers in 1980s Italy who dig into tombs of the ancient Etruscans. They’re after profit, but their leader, a lovelorn English expat (Josh O’Connor), has weightier matters on his mind. Rohrwacher’s direction synthesizes the divide between worldly pleasures and immortal souls. She’s a remarkably playful filmmaker, unafraid to throw in a musical number or direct address to the camera, and she makes the question of what we owe history feel tactile and immediate. Also: O’Connor’s wardrobe will delight and enthrall the menswear enthusiast in your life. —Nate Jones

Hit Man

Richard Linklater’s new film is as effervescent as a freshly cracked Topo Chico, and a generous helping of all the things that people have been claiming they miss at the movies. It’s a comedy and a thriller, it’s got some real moral ambiguity, and it feels grown-up in the least lugubrious sense of the word, even when its main character is delivering lectures on human nature in the context of his day job as an adjunct professor. Most importantly, it’s sexy, with Glen Powell and Adria Arjona displaying the kind of chemistry that turns a casual conversation into something that makes you blush. Powell, who co-wrote the film, sets out to prove he’s a genuine movie star as Gary Johnson, who works part time for the police department pretending to be a hit man in stings to catch would-be killers. And, by God, does he do it — he’s larger than life and spectacularly, absurdly appealing. —Alison Willmore

Dicks: The Musical

The pitch for Dicks is that it’s The Parent Trap but with more gay incest: Co-creators Aaron Jackson and Josh Sharp play two extremely successful, extremely straight vacuum-parts salesmen who begin as rivals, then become best friends after they learn that they are actually long-lost identical twins. They, too, embark on a twin-swapping scheme meant to reunite their divorced parents, except here Mom (Megan Mullally) is around 100 years old, and Dad (Nathan Lane) keeps two murderous foot-tall mutants he calls his “sewer boys” in a cage in his apartment. It all went down like gangbusters in the specific context of a midnight festival premiere — which climaxed with inflatable penises raining from the balcony and a local choir singing a heartfelt ballad about God being gay — and I have absolutely no idea how it will play outside it. —N.J.

American Fiction

Cord Jefferson’s directorial debut, adapted from Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure, is a darkly funny satire of the publishing industry about an embittered academic who, after having his work rejected for being inadequately Black, coughs up a manuscript filled with clichés about urban suffering that becomes an unplanned hit. But it’s the family drama that makes the movie so memorable, with a particularly fine turn from Jeffrey Wright as Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, whose frustration toward the literary world is revealed to be part of his general aloofness from everyone who’d like to get close to him. Monk’s relationships with his grown siblings (played by Sterling K. Brown and Tracee Ellis Ross), as well as with a potential girlfriend (Erika Alexander) and his mother (Leslie Uggams), make the film as much about aging and professional disappointment as it is about the racial condescension of an industry. —A.W.

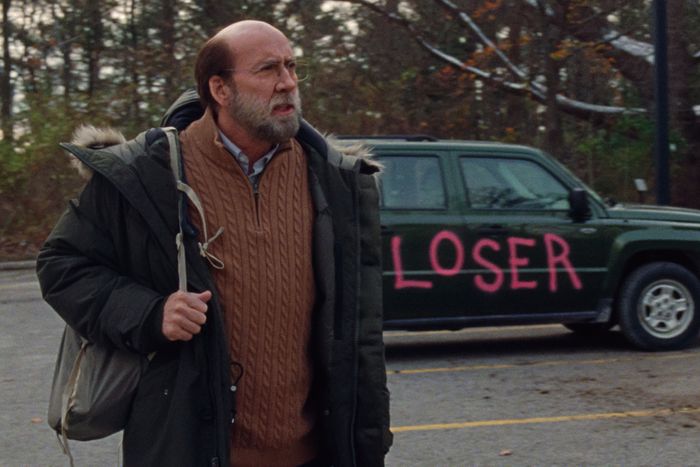

Dream Scenario

One day, a “perfectly average Mr. Nobody” named Paul Matthews starts inexplicably popping up in strangers’ dreams. Not as the star, more like a featured extra. This naturally makes him incredibly famous overnight, even though, as Paul notes, he hasn’t actually done anything. Norwegian director Kristoffer Borgli has a killer concept and perfect casting. Because Paul is played by Nicolas Cage, an actor who’s intimately familiar with the phenomenon of strangers carrying around an idea of him in their heads. As the buzzwords like trauma and lived experience pile up, it becomes clear that what had initially appeared a dark satire of the fame economy also wants to be a parable for cancel culture. That’s where many critics jumped off, but not me. The film also pokes fun at right-wing grifters, and besides, a lot of the jokes — in particular, one in which a gym full of undergrads undergo exposure therapy to Paul — are quite funny. —N.J.

Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World

The second part of Radu Jude’s newest comedy consists entirely of a locked-off shot of a family standing in front of the factory where one of their members was injured while on the job. It’s a depiction of the worker safety video shoot that PA Angela (Ilinca Manolache) has been spending all her time setting up, constantly on the road looking for subjects on a schedule that has, ironically, put her in danger of falling asleep while in front of the wheel. Jude’s movie is profane, clever, and far-ranging in its themes, which touch on everything from labor and globalism to whether German schlockmeister Uwe Boll (who plays himself) was enacting the history of cinema when he beat up his critics in a boxing ring. But the final sequence, while caustic in its implications, is also just so hilarious in the precision of its execution, a reminder that, in addition to being daring, Jude is one of the funniest filmmakers working today. —A.W.

Evil Does Not Exist

Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s mesmerizing follow up to Drive My Car is about a rural community a few hours outside Tokyo that’s been chosen to be the home of a future glamping site that threatens to disrupt the environment as well as the peaceful life of the existing residents. The film is as unhurried as the rhythms of that countryside existence, which includes hauling water from the spring and harvesting wild wasabi to be used in seasonal dishes at the local udon restaurant. Eventually, respected local handyman Takumi (Hitoshi Omika) finds himself spending the day with two of the employees from the company proposing the site, a pair of city-dwellers who’ve begun questioning the ethics of what they’re doing. But what makes Hamaguchi’s film so haunting is not its beguiling atmosphere but the unexpected and enigmatic ending, which gives everything that’s come before a different, and less comforting, context. —A.W.

His Three Daughters

15 years ago, a movie like Azazel Jacobs’s latest would have been snatched up by a Sony Pictures Classics or a Fox Searchlight and become an indie hit for its beautifully performed depiction of a trio of sisters who’ve gathered for their dying father’s last hours. Unfortunately, it’s 2023, and no one seems to know how to release a movie this delicate and wise, which is a shame. Carrie Coon, Natasha Lyonne, and Elizabeth Olsen are all very good as very different women who’ve drifted apart in adulthood and who end up hashing out old grievances and current tensions. Like American Fiction, His Three Daughters is a film about trying to figure out the kind of connections you’re going to have with your siblings once the remaining parent who tied you all together is gone. It’s wonderful, wistful, and sad without being maudlin. —A.W.

The Boy and the Heron

The Boy and the Heron is being described as the last film from Hayao Miyazaki, who’s now 82 years old. But that was how 2013’s The Wind Rises, which was meant to mark the start of the animation master’s retirement, was framed as well. As long as Miyazaki feels he has more to say, we’re lucky enough to be here to receive it, and this latest work comes off as acutely, if indirectly, personal. If The Boy and the Heron ultimately feels less universal in its emotional appeal than past Miyazaki work, it’s only because Miyazaki is grappling with something very specific — that we can’t leave the world behind when we’re a part of it. —A.W.