In honor of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, we’re republishing our 2020 review of Wild Style. For more on rap’s best “process” documentaries, head here.

Held in an abandoned massage parlor on 41st Street, the Times Square Show of 1980 represented a pivotal moment in the rise of several New York subcultures. An informal, grassroots exhibit bringing together more than 100 artists — some of whom, like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, would go on to become major cultural figures — it was a raucous, inclusive affair, featuring everything from painting to video art to fashion to music to performance, much of it created by relative unknowns. The young No Wave filmmaker Charlie Ahearn was there, too, screening his homemade super-8mm kung-fu feature The Deadly Art of Survival, which he had made with a group of young Black and Puerto Rican martial artists on the Lower East Side. It was at the Times Square Show that Ahearn met budding artist Fred Brathwaite, a.k.a. Fab 5 Freddy (later to become the first host of Yo! MTV Raps), and they started to dream up 1982’s Wild Style, a love song to the city’s graffiti artists and one of the earliest, most momentous portraits of hip-hop culture committed to film.

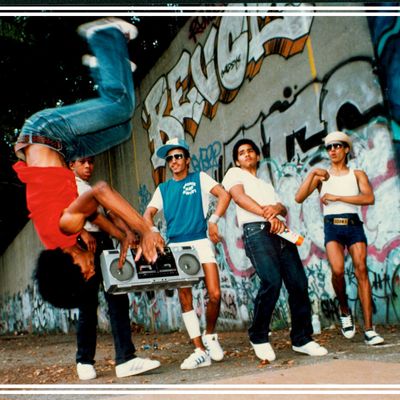

Wild Style was shot on location in and around the Bronx, starring real-life graffiti writers, breakdancers, and rappers, many of them playing either variations of themselves or, simply, themselves. Made for very little money, it embodies the DIY aesthetic of its milieu, an anything-goes world where vibrant murals coexist with seemingly bombed out buildings. Brathwaite (who helped conceive the story, co-produced, co-starred, and oversaw the music) saw hip-hop as belonging alongside those other 1970s New York subcultures, punk and new wave, which represented a lot more than music and seemed to have emerged from the very geography of the city. “I wanted to show that for a culture to be complete, it should combine music, dance, and a visual art,” he said in Complex’s 2013 oral history of the film. And so, Wild Style drifts from a rap-battle-cum-pickup-basketball-game to an impromptu performance by the legendary dancers of the Rock Steady Crew to a performance by old school rap legend Busy Bee to a record-scratching clinic by Grandmaster Flash, often with the slenderest of narrative motivations.

All that is probably why Wild Style often feels more like a documentary than a fictional drama. (As many have noted, you could cut about 15 or 20 minutes out of it and you’d be left with a literal documentary.) The story feels at times like a series of familiar setups without much follow-through. Our protagonist Ray (played by Lee Quiñones, himself one of the city’s most legendary subway artists and, along with Ahearn and Brathwaite, one of the key conspirators behind conceptualizing the film), a talented graffiti writer who covers entire train cars under the mysterious name of “Zoro,” pines for his ex-girlfriend Rose (Sandra “Lady Pink” Fabara), a beautiful fellow artist who has started working with a slightly more legit group calling themselves the Union. With the encouragement of local impresario Phade (played with buckets of charm by Brathwaite himself), Ray is approached by a journalist for the Village Voice (actress and gallerist Patti Astor, looking like a dead ringer for Debbie Harry, whom the filmmakers originally tried to cast) working on a big feature about graffiti. Taking Phade and Ray to an upscale Upper East Side cocktail party, she introduces them to some snooty art-world types in the film’s sole detour into social satire. Meanwhile, Phade hires Ray to do a big mural for a rap convention he’s organizing in an abandoned Lower East Side amphitheater.

None of these various subplots results in any escalating drama: Ray and Rose get back together pretty quickly, and the Union is never heard from again; Ray’s sojourn into the cocktail party world winds up with his host (art collector Niva Kislac, basically playing herself) seducing him, and not much more; the rap convention goes off pretty much without a hitch; Phade seems at times like an oily opportunist, but he ultimately does right by everybody. Ray’s brother, briefly back home from the army, criticizes his fondness for graffiti, but there’s precious little mention of the city’s ongoing war against subway writers; that this is a valid art form is mostly accepted as fact by the film. Any other movie would stretch these various subplots out, mining them for narrative tension and moral messaging. Dreams would be dashed, plans would be thwarted, friendships would be betrayed, romances shattered. Someone would get arrested, or killed, or at least shot. And of course, the blasted, decaying backdrop of the Bronx would somehow scuttle everyone’s dreams and desires. But no such thing happens in Wild Style. Ordinary people carry on and live their lives, and do their best to make their spaces beautiful with art, music, movement. The world drifts along as in a Zen dream. And that’s where the film’s own artistry lies.

There’s a warmth and inclusiveness to Wild Style that makes you want to step into this universe. It would have been easy — and probably far more commercial — for Ahearn and Brathwaite to turn this into one of those beaten-down-protagonist-makes-good pictures and show Ray rising above his milieu, using his talents to leave this urban hellscape behind. But their communitarian ethos flies against that idea. Yes, Ray is unique, and yes, he’s a bit of a loner, but he’s not looking for a ticket out; he’s looking to express himself. And so, too, is everyone else. When Astor’s journalist, arriving in the neighborhood for the first time, tells a large group of curious kids that have gathered around her that she’s looking for a graffiti artist, they respond, cheerfully, “We’re all graffiti artists!” The rapping, the dancing, the writing, the scratching — it all seems to exist in an egalitarian continuum. The guys with the mics rhyme not from a proscenium, but amidst the crowd. (Though the film’s climactic performance, happening as it does on a massive stage, strikes a poetic and prophetic note about the fact that all these art forms are about to explode.) This is a world where anything seems possible, which seems quite bracing given the way that the inner city, particularly in New York, was depicted in the early 1980s.

Ahearn is not the kind of polished, film-savvy director who does camera tricks or tries to make a $5 budget look like a $5 million one. His close-ups are a little too close, and his screen direction is sometimes a mess, but that also lends the picture an irresistible immediacy and authenticity; it feels like something that has emerged from this world, shot on the fly and full of stolen moments. But it is this very aesthetic approach that makes the film so compelling and unique. In one of Wild Style’s most remarkable scenes, the Cold Crush Brothers and the Fantastic Freaks, two rival crews, engage in a rap battle, which then extends to a pickup basketball game, with members confronting each other with rhymes while dribbling, shooting, passing. If the scene were more polished, it would look ridiculous — like a tacky attempt to update West Side Story. But Ahearn’s rough-edged, handheld, off-the-cuff style sells us the paradox: The beef is simultaneously huge and no big deal, an impromptu ritual.

Wild Style is credited as the first hip-hop movie, but it didn’t introduce rap or hip-hop culture or even the notion that graffiti could be art. There had already been major gallery shows featuring graffiti artists by 1981, and by the time Wild Style was released in late 1983, bigger productions capitalizing on rap and the break-dancing craze were already underway. (Beat Street and Breakin’ came out in 1984.) Wild Style arrived early, but it wasn’t so much ahead of the curve as simply well-placed to ride it. Plus, Ahearn was smart enough to use guerilla tactics to promote his feature, paying high school kids to distribute flyers at their schools. When it opened on 47th street — just steps away from the grindhouses that showed the Bruce Lee flicks Ahearn loved so much — Wild Style was, for a while, the second highest grossing release in New York City, behind Terms of Endearment.

It arguably had a greater impact abroad: The film actually premiered in Japan before it opened in New York, and the cast and crew were treated like rock stars on a tour of the country. After German TV broadcast it in the 1980s, Wild Style became a phenomenon among German youth on both sides of the Berlin Wall, in particular the children of Turkish immigrants. (Years later, when the cast and crew reunited for a tour of Germany, they proudly pointed out that sections of the Wall had been artfully enhanced with Wild Style graffiti.) Something similar happened in the United Kingdom and across Scandinavia. One savvy Caribbean entrepreneur reportedly bought a 35mm print of the film and traveled around the islands by boat, screening it to adoring crowds. Whether broadcast or bootlegged, Wild Style served as an introduction for kids around the world to a thriving, dynamic newfound American counterculture.

And it continued to be a kind of cult movie for decades, its legacy kept alive through references and samples by the likes of Nas, the Beastie Boys, Cypress Hill, and others. After a restoration and re-release in 2007, the film would become better known and more widely available. Today, of course, it can be enjoyed partly as a nostalgia trip, a time capsule of a pivotal period in New York and hip-hop history, right before everything went stratospheric. But that would be, perhaps, to undersell what makes it so special. Ahearn and Brathwaite’s decision to downplay the drama and to focus on an honest, ground-level portrait of this world and how it saw itself means that Wild Style hasn’t really dated. It feels just as fresh today as it did back then, a vital look at what spurs us to create and to dream.

Wild Style is available to watch for free on Tubi or Crackle, or with a subscription to Kanopy, and is available to rent on Prime Video, iTunes and Google Play.

More From This Series

- Helen Hunt Answers Every Question We Have About Twister

- Mr. and Mrs. Smith Is a Straight Shot of Movie Star Charisma

- Scott Speedman Answers All Our Questions About Underworld