Editor’s note: In 1985, coming off the success of Yentl and more than a decade of mostly rock and pop recording, Barbra Streisand began work on what was to become The Broadway Album. At the time, the revival of interest in the Great American Songbook was just beginning, and conventional wisdom held that Broadway-style music was old-fashioned and unlikely to sell records. In this exclusive excerpt from her memoir My Name Is Barbra, published today by Viking, Streisand recounts the uphill battle with her record company to get it made and her collaboration with the songwriter and composer Stephen Sondheim on the album’s defining song.

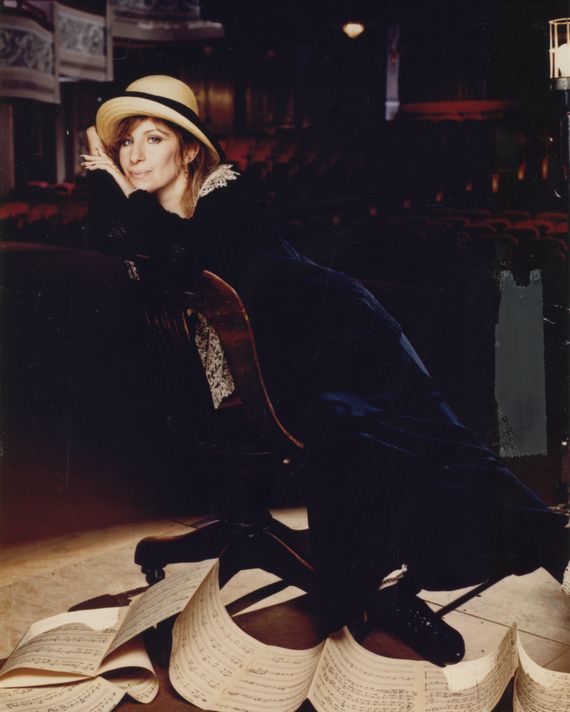

For my next album, I wanted to go back to my roots. And that meant Broadway, where I got my start as an actress. Some of the best songs ever written were conceived for Broadway musicals, which are now recognized as a uniquely American contribution to culture. This is the music I first heard as a teenager, watching the movie versions at the Loew’s Kings in Brooklyn and then taking the subway to Manhattan to see them live onstage. This is the music I love.

When I approached Columbia with my idea, Walter Yetnikoff and the other executives were apoplectic. “Are you kidding?” they said. “Nobody’s interested in Broadway songs. It’s old‑fashioned. It’s not commercial. We want you to do pop songs. Make another contemporary album.”

“Great songs will always be contemporary!” I said.

I had been with Columbia for 23 years. I had made 23 albums (and ten soundtrack or compilation albums) for them. And now, after five No. 1 albums and seven Grammy awards and millions of dollars in record sales, I basically had to sell myself again. It was actually kind of humiliating.

I was hearing the same sort of thing I’d heard all my life, ever since I was 18 years old … “Why are you singing these cockamamie songs?” “It’s not what’s selling nowadays.” “The whole idea is too risky.”

In other words, “no.”

And this is why I’m so grateful to my manager, Marty Erlichman, because when I asked for creative control before I signed my first recording contract, he got it for me. That meant I could make any album I wanted. But the record company informed me that they wouldn’t give me my advance and wouldn’t count the album toward fulfilling my contract unless it sold 2 and a half million copies, which they clearly thought it wouldn’t.

Well, that was all the challenge I needed.

And I thought, Why not use the truth? Why not be honest about the opposition I was facing? And it just so happened there was a song that dealt with this age‑old conflict between art and business. It was called “Putting It Together,” and it was from a musical called Sunday in the Park With George, written by the extraordinary composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim.

He’s the rare composer who is equally gifted at both words and music. It’s a rich talent … rich in substance and wit. You can’t help but be dazzled by the intricacy of the rhymes, the delicious double entendres, and the clever plays on words.

He deals with big emotions and also the most subtle feelings, often with a dash of irony that can suddenly change the mood from sunny to something darker and more poignant. He understands passion and can capture it in a lyric. His insight into human nature is profound. As an actress, I’m given so much to work with because there are so many layers to each song.

They’re also interesting to sing because the rhythm is built into the phrasing. And as with the best melodies, it all seems inevitable. Everything just fits and feels right. And by the way, I’d like to thank him for putting the high notes on the vowels! Like the greatest songwriters, he knows how to write for singers.

Steve had distilled all the struggle, anxiety, antagonism, and excitement experienced by any artist into “Putting It Together.” The only problem was that it was about the art world and a visual artist (George Seurat’s grandson, who worked with lasers and light), rather than a recording artist.

But I had an idea, and I needed to talk to Steve.

I told him how much I loved the song and explained how it resonated with me. “I’m going through the same thing with my record company, and I want to use your song to set up the whole album.”

Then I took a deep breath and said, “So, is there any possible way … I know this is a lot to ask, but would you be willing to rework the lyric to make it about the recording industry?”

He thought for a moment (which seemed an eternity to me) and then said, “Sure. I’ll try.”

I was so excited I almost fell off my chair. You have to understand how remarkable that was. Most songwriters would simply refuse to change the lyrics to a finished song. But Steve believed, as I do, that art is a living process. It’s not set in stone. And because it lives and breathes, it can change.

That phone call led to many more.

Steve told me that at first he thought it would be simple … that he could just change the line “I remember lasers are expensive” to “I remember vinyl is expensive.” But then as he went through the song, he realized that all the references to the art world would have to shift to the music world. And that meant unraveling the rhymes and coming up with new ones. As he wrote in his own book, Look, I Made a Hat, “I felt beholden to someone who wanted to make the song so personal, and guilty about skimping on the obligation to make it as pertinent as possible.”

For instance, I told him, “I can’t believe that I’m still auditioning for this company after 23 years. Can you work that into the lyric?”

And he was so adept that he took my thought and turned it into these lines:

Even when you get some recognition, everything you do, you still audition

It was such fun working with Steve. In fact, it was one of the best collaborations I’ve ever had, because we’re both New Yorkers. We talk fast and we think fast, so we were speaking in shorthand half the time. We didn’t even have to finish a sentence because we already intuited what the other was going to say. It was exhilarating to be so in tune with someone. There were moments when I was screaming with joy over the phone.

We made a pact. If we disagreed about something, whoever felt more passionate about it would win. I think our only tiff (I can’t call it an argument … it was more of a debate) was about these next lines:

If no one gets to see it, it’s as good as dead

A vision’s just a vision if it’s only in your head

I thought he could change it to “if no one gets to hear it,” but Steve objected. He said, “How can you hear a vision? You can only see it.”

I said, “That’s if you’re thinking of a painting. But when I’m thinking about music, I can hear it in my head … meaning, I hear the record finished. It’s a musical vision.”

Now I can’t even remember who won. I had to pull out the album and listen to the song. And I say “hear.” So I must have convinced him, although in his book, the revised line is written as “If no one gets to share it.” He solved it so we both won!

I even managed to persuade him to come to Los Angeles and stay with me so we could work more closely. I basically held him captive for several days. I remember a moment when we were out on the patio of my Art Deco house, sitting by the outdoor fireplace.

“Steve, the new lines are fantastic.” (I began with the good news and then gingerly continued.) “I know you’ve already changed so much and I hate to ask, but about the ending —”

“What?”

“I need a longer one … eight more rhymes.”

I’ll never forget the look on his face. He said, “Yesterday I gave you eight new rhymes!”

“I know, I know … but I think we need eight more. The song is so exciting … it’s building to the climax. People will hear me practically gasping for breath. And just when you can’t even imagine that there could be another rhyme, there is! They just keep coming and coming, one right after another! It would be incredible!”

He walked away, shaking his head in disbelief. I think he wanted to strangle me. But the next day he handed me eight more rhymes, and they were brilliant. The work he did on this song was genius, and Steve was with us in the studio when I recorded it.

It was an exciting day. Not only were we recording the song … my company, Barwood Films, was also filming a behind‑the‑scenes look at the process (for what became an HBO special called “Putting It Together”: The Making of the Broadway Album). So the place was packed, with a camera crew and the soundmen and all the recording engineers, plus Peter Matz, conducting the orchestra.

And, to make things even more complicated, I had come up with another idea. At the beginning of the song, I thought it would be interesting to hear some male voices dismiss the whole idea of the album, just as the Columbia executives had done. (My theory is that in some cases, the Establishment wants to be the artist. They are secretly jealous of the artists and their power to create.)

So I wrote up a version of their conversation and asked three friends to come in and play the executives. Sydney Pollack was game … it was a nice turnaround to direct him after he had directed me in The Way We Were. Then there was David Geffen, who had his own record company, so that was basically typecasting. And Ken Sylk, who was the only professional actor in the bunch. I planned to intercut our dialogue with the lines of the song, and of course I was rewriting at the last minute as we tried various things.

So there were a lot of moving parts, and naturally I wanted to do it live … in the moment and in a complete take. That would give each performance the kind of energy I love. It was very tricky because it had to be perfectly timed, with everyone saying their lines at just the right moment. And I had to switch back and forth between talking and singing. And the tempo of the song starts out slow but then gets very fast very quickly … boom boom boom. There are lots of words to say very rapidly, and there’s no leeway. You have to do it exactly as written, or it all falls apart.

The guys were nervous about doing it all in one take, so I told them that we’d break it up into two segments … first the short part, where they’re telling me not to make the record, and then the bulk of the song, where I’m singing and they just come in at intervals. I tried to reassure them. “Listen, it’s just a conversation between you and me. You’ve got the script, and if you make a mistake, don’t stop. Just go on.”

They still looked scared.

I said, “Relax. Just play with me. This will be fun!”

We went through the lines one more time, and I thought we were ready to do a take. The guys went into their booth, and I had one last talk with the cameramen to confirm that they knew what to do.

Then I went into my booth, put on my headphones, and said, “Can somebody say take one?” Peter cued the orchestra, and we were off … like runners at the starting line. Amazingly we got through the first segment and then everything paused for a moment. I went over to the guys to compliment them and make sure they were good to go on and then I pinned up my hair and went back into my booth. Now the pressure was on me. This was the bulk of the song … about four minutes, but it felt like 15, because the song was so complex.

I looked at Peter and said, “I’m ready.” The orchestra started up, and somehow I managed to do the whole thing in one take! I felt as if I had just run a marathon. And I was so happy that we got that performance on film and on tape. In the recording studio, just like on a film set, my first take is often the best.

But the guys forgot to come in on some lines.

I looked at them and said, “Vat happened, my darlinks?”

“We started listening to you singing!” David said.

We all laughed, and I walked out of the booth, so glad that I had managed to do the whole song in that first take. I could always fix the guys, but I couldn’t easily replicate that first performance.

I went over to rehearse with them and then Peter came over and said, “We’re ready for take two.”

I said, “Wait, before I do another take, I want to hear the one I just did.”

And then something happened that had never happened before, or since. I was told it no longer existed. What?! Somehow my vocal track on that first take … the most alive, with the most energy, on pitch both vocally and emotionally … had been erased.

I think I lost my breath. I had to sit down. In my entire career no one had ever erased a vocal track without asking. You don’t do that to any performer.

I was aghast. How could this have happened?

Back then we had only 24 tracks to work with (today, in the digital era, they’re virtually unlimited), and apparently someone needed another track. To this day I don’t know if it was Peter or Don Hahn, the engineer, who had decided to erase my first take, probably assuming that I’d be doing more.

Lesson No. 1: Never assume.

So the sound you hear on that song in the TV special was taken off a basic two‑track Nagra used by the video crew (to tape interviews, not music) … good enough for TV but not for the album. I had to do 16 more takes in the studio that day (because I was so upset) and put the best pieces together … so the title of the song came true, in real life.

One last thing about the special. I wanted to replay the vocal to “Putting It Together” over the closing credits, and as we were editing, I suddenly had an idea for the perfect ending. So I wrote it out and now the very last words you hear are Sydney saying a bit sheepishly, “Well, I guess we were wrong.”

And David responds, “Wh‑wh‑what do you mean we? I had to beg her to make this album!”

And then you hear the last three notes from the orchestra, for a rousing finish. I thought it was funny, and ironic as well, to have the head of the record company (the imaginary head, of course!) rewriting history and claiming credit for the idea he initially dismissed!

By the way, the album went to No. 1 on the charts and became a huge success. (I’ve been told it has sold 7 and a half million copies worldwide.) It was nominated for a Grammy as Album of the Year, and I was thrilled to win the Grammy for Best Pop Vocal Performance, Female.

Point is, it definitely qualified for my contract!

From My Name Is Barbra by Barbra Streisand, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Barbra Streisand.