Ed. note: It’s the third and final week of my January adventure. I’ve been keeping a diary of the month’s festival offerings, and you can catch up on my previous entries here and here. Also, I heard a rumor that UTR founder and director Mark Russell is offering a bottle of whiskey to anyone who sees all the shows, so here we go. (Mark, I like heavily peated Scotch.)

.

Monday, January 15

Hello, La MaMa, my old friend. Tonight I’m at the La MaMa space known as the Club for a short and intense piece by the theater company Motus. This Italian/itinerant outfit was founded in 1991 by Enrico Casagrande and Daniela Nicolò, who are also the creators of this show, Of the Nightingale I Envy the Fate (or, in Italian, Dell’usignolo io invidio la sorte). The words belong to Cassandra, the Trojan prophetess doomed to be disbelieved. In the Oresteia, she mourns bitterly that, while the nightingale at least has wings and a “sweet song that covers every lament,” the gods have fated her “to be ripped apart / by a terrible double-edged axe.”

The show’s program note describes it as a “performance-cry,” and that feels pretty apt. Of the Nightingale is a 45-minute thrashing, crawling, pulsing solo dance, designed both to exhaust and exult its performer, Stefania Tansini. In slick, cream-colored knee-high boots (with chunky enough heels to make me wince for her knees), neon-pink feathers for eyelashes, and several pieces of creepy-crawly custom latex implying an exposed spine and lower rib cage, Tansini looks ready for the kind of club that opens at 4 a.m. in Ibiza. But that’s part of the point — she, Nicolò, and Casagrande are playing with the myth of Cassandra’s enforced silence not only as a symbol of oppression but as a form of perverse sex appeal. The woman who’s seen and not heard: You can watch her dance, and you don’t have to listen to her. (The character’s fate is exactly that dark: After the fall of Troy, she’s taken back to Greece as a sex slave — sorry, “concubine.”)

As dense techno beats throb and LED lights flash, Tansini’s Cassandra performs a defiant funeral dance for herself. The words “We were never meant to survive,” from Audre Lorde’s “A Litany for Survival,” echo throughout the piece, and for this Cassandra — along with her convulsive assertions of bodily autonomy despite everything — they form a subversive battle cry. At one point, Tansini crawls underneath the long piece of Mylar that has been her dance floor, stretched like a runway between two audience banks. We watch its surface ripple and bulge as she burrows down the length of it and emerges into the hot glare of a footlight: Bury me, the prophetess is saying. The truth never stays dead.

Of the Nightingale isn’t a subtle show, but why should it be? It’s got the energy of a night blowing your eardrums out on a subterranean dance floor, or an antiwar protest at a heavy EDM concert, and Tansini’s twisting, exacting limbs and feather-fringed, severe gaze are captivating. In fact, her eyes do some of the most compelling choreography in the show. As Of the Nightingale begins, she stands frozen, only her face lit in the darkness, her mouth plugged with what looks like a kinky bronze lock that she wears on a chain around her neck. Birdsong flicks and flutters in the air and her eyes follow it, darting side to side, blinking and rolling with every tiny quiver in the melody. Only gradually do you realize that she’s scoring herself — the thing in her mouth is a whistle, and she’s playing an ever more shrill and manic tune, dancing along to it with only her glance. Whatever the legends say, this Cassandra has our attention.

.

Tuesday, January 16

On further contemplation, I think subtlety may be dead. Or in cryo-sleep, waiting for a different era. Not that meeting such a relentlessly appalling moment with raised voices and raised fists is — artistically speaking — necessarily a bad thing. Both the whisper and the howl can be done well, or not so well.

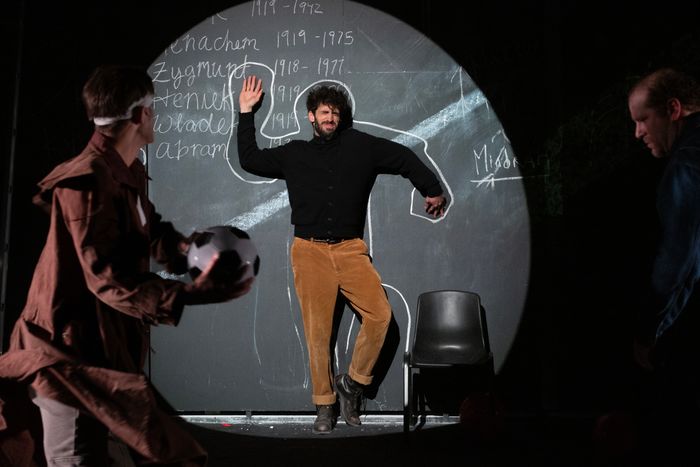

Our Class, written in 2008 by the Polish playwright Tadeusz Słobodzianek (now making its long-incoming New York premiere at BAM in a production from Arlekin Players Theater), is aiming for the howl, but the show’s got a frog in its throat. I don’t know if Norman Allen’s English adaptation lets down the original text, but at least here, Słobodzianek’s play comes across as ungainly and tensionless, even as it attempts to turn a more intimate and perhaps less familiar lens on the 20th century’s most frequently retread horror.

The story — told almost entirely in past-tense narration by its ensemble — is rooted in the real events of 1941 in the Polish town of Jedwabne. That summer, the town’s own Polish inhabitants (not the occupying Nazis) massacred its 1,600 Jewish citizens, locking most of them inside a barn and burning them alive. This horrific pogrom creates the fulcrum for Słobodzianek’s play, which follows ten classmates in Jedwabne, five Catholic and five Jewish, from early childhood to the end of each of their lives. We can guess — and not just from the literal writing on the set’s large, blackboardlike back wall, where the actors are scratching out a list of characters’ names and life spans before the show begins — that only some of the children we meet will live to see old age.

That “we can guess” is the persistent problem with Our Class, one that’s extant in Słobodzianek’s script and only exacerbated by director Igor Golyak’s gesture-happy production. Though it clearly makes no sense to complain that a story about Holocaust atrocities is too predictable, or too heavy, a work of theater requires more than thudding inevitability to power it through. Golyak on some level seems aware of this and tries to add energy through directorial flourishes: Both acts of the show begin with the house lights on and the ensemble seated, reading from their scripts, even sometimes calling for lines when they look up from the books. Little by little, in each act, the theatricality gets layered in, and the “staged reading” concept falls away, replaced by a haphazard collection of directorial choices that, while admirably nonliteral, are neither revelatory nor consistent. At one point, balloons represent Jewish souls — and as soon as we see them, we know that their strings will be snipped and we’ll watch them float up toward the ceiling. Characters are pelted with chalk dust or soccer balls or sprayed with water to represent beatings or torture. Actors speak into handheld live-feed cameras, their faces projected on a screen, when writing letters to each other. There’s a lot of moving of ladders, lots of writing in chalk, lots of images that — in isolation, in and of themselves — might have some interest or resonance to them but fail to cohere into a potent, graceful theatrical vocabulary.

There’s the crackle of potential in Golyak’s box of toys, but his production’s big-C Choices end up in one of two traps: Either they come across as aesthetic spitballing, or they’re too leaden to thread their way into our hearts. The major exception is Eric Dunlap’s lovely projection design, which enhances the real chalk on the blackboard wall so seamlessly that you sometimes wonder how an actor managed to sketch something up in that corner 15 feet off the ground.

It also doesn’t help that Our Class features not one but two brutal onstage rapes, and that these are the places where Golyak chooses to go with mostly representative rather than imagistic staging. I’m not objecting to the content per se — these things happened (and happen), and they’re part of what we’re being asked to sit with. But why, in a stage world where a snipped balloon shows us death, make the decision to pile three thrusting men on top of a woman? The theatrical language gap is jarring, and it does nothing to ameliorate the already wince-inducing nature of some of Słobodzianek’s writing. “I couldn’t forget … Rysiek’s eyes,” says Dora (played by the willowy, intriguing Gus Birney), naming one of her former classmates who have just raped her. “They were wild, but wild and beautiful.” In the words of Randy Jackson, yeah, that’s gonna be a no from me, dawg.

.

Thursday, January 18

This weather and schedule caught up with me a bit yesterday, and I had to take a moment to reset. But now I’m back at La MaMa for almost two and a half intermissionless hours of new experimental opera. I have done my lower-back stretches.

This is Chornobyldorf, my first dip into the Prototype Festival. The show — composed and co-directed by the Ukrainian musical multi-hyphenates Roman Grygoriv and Illia Razumeiko — describes itself as an “archeological opera in seven novels” and also, borrowing the term coined by Umberto Eco, as an “opera aperta.” Eco’s phrase, meaning literally “open work,” points at a kind of expansiveness, a porousness and flexibility in an artist’s vision where meaning is manifold and shifting; where the presence of an audience activates and changes the results; where the project will always be, in essence, unfinished.

That should be true of theater as a whole — or at least a damn sight more of it — but, for the moment, at least Grygoriv and Razumeiko haven’t misspoken. Chornobyldorf is a musically rangy, physically risky, wide, deep, and wild piece of work. As an intentional act of ecstatic endurance, for both performers and audience, it leaves you feeling somewhat drugged — as if we’ve all been acolytes in some ancient ritual, and we’ve spent the last two hours stripped naked, inhaling the smoke of various psychotropic herbs.

A good portion of the cast — including the composer-directors, who also play in the small and sternum-rattlingly mighty orchestra — do spend much of the show naked. And watching Grygoriv and Razumeiko leave behind their microtonal bandura and guitar, strip and join the cast onstage, then climb back into the pit to keep playing, still undressed and stone-faced the whole time, is one of the most weirdly delightful and also absolutely metal things I’ve seen in a while.

The show is a ritual — a series of rituals, in fact, though the context is not ancient but postapocalyptic. If that word makes you picture something lazily reminiscent of Mad Max or Blade Runner, don’t fret. Chornobyldorf isn’t skimming its imagery from dystopian Pinterest — it’s digging into the wracked and radioactive soil of its own backyard. In seven movements (or “novels”), and backed by a series of striking films taken of disastrous postindustrial landscapes, the company of Chornobyldorf enacts a collection of strange, investigative rites. Their characters inhabit a blasted and cultureless future — here, they appear as pagan priests and priestesses, or perhaps simply visionary scavengers, who, scratching through the rubble, have unearthed broken artifacts and bits of detritus and turned this societal refuse into objects of fascination and worship. Two singers wear what appears to be traditional Ukrainian dress, but the garlands in their hair are tangled electrical wires and the patches on their sleeves are scraps of circuit board. A ballerina dances jerkily along to a sinister player piano that sprouts cables like weeds. A musician plays an incredible contraption that looks like three trombones soldered together. Even the instruments have mutated.

This defamiliarized experimentation with fragments of a lost world feels both feral and transcendent. It’s gritty and fleshy in its detail even as it’s all — the whole groping, knowledgeless effort — a search for the divine. In this way, Chornobyldorf reminded me of only one other piece of dystopian literature, Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker. It’s a book where you learn the language gradually, almost by osmosis — as is also true of this opera aperta, which contains everything from shreds of Bach and Mahler to microtonal scales, Ukrainian polyphonic folk song, and heavy metal. Once you sink into the patchworked, crusty patois of Riddley’s narrator, you realize that you’re in a new Stone Age, but everything changes when the hero digs up the remains of an ancient Punch and Judy puppet show. In Riddley, and in Chornobyldorf, we are made human by the pull of art. Our primal impulses are imaginative, creative, and — be it for birth or wake, spring or winter — celebratory.

.

Friday, January 19

It’s Dynasty Handbag day! I’m seeing Titanic Depression, a solo show by the writer and performer Jibz Cameron in her pants-averse alter-ego, the aforementioned Ms. Handbag (Mx.? Miss? Captain? Esquire? I should have asked.) Before the play begins, we’re treated to a screensaver-esque undersea-scape projected on the back wall. Normal flotsam and jetsam drift by: a Doritos bag, a Coke can, an Amazon Prime bubble envelope, a couple of mermaids, a skeleton pirate rowing a boat named Booty Thief, a guillotine, a Viking dressed in armor made of Natty Ice boxes. Cameron hosts a monthly variety show called Weirdo Night, and … 🎵I think I’m gonna like it heeeere. 🎵

Dynasty Handbag wears a black bouffant that looks like it’s been through a lawn mower and the kind of makeup job a 9-year-old would enthusiastically perform on a younger sibling. There’s a whiff of Helena Bonham Carter in her Tim Burton phase, if she were also the sort of person to, I don’t know, walk a pet tortoise and own every John Waters film on VHS, and also Con Air. Dynasty shuffles and hunches her shoulders and peppers her deliciously meandering conversation with words like “impreganodado” and profound reflections such as “Aren’t all dancers doulas?” and “Isn’t it great we can all enjoy our priv of getting to be here and do thea-tray?”

The thea-tray she’s here to do is an homage to/send-up of the 1997 megahit by James Cameron (no relation to Jibz). Dynasty stars as the Rose character, and also as her stuck-up mother via some wonderfully janky video edited by Mariah Garnett, in which stock backgrounds (watermarks still attached) are mashed up with Cameron’s own animations of character bodies, to which film of Dynasty’s talking costumed head is attached. Her drawing style has extreme Squidbillies vibes — and Dynasty-Rose’s artsy, belowdecks Leo love interest here is an octopus that she names “Hat.” You just know that the car sex scene is going to be great — and sticky — and it is.

It’s stupid-smart-bizarre-silly fun to watch Cameron dig through a costume trunk (“too gay,” she says as she discards a yellow latex leotard), or interact with the stock-photo rich dudes who populate the ship’s smoking room (John Jacob Astor and J.P. Morgan are there, and so are Bezos and Musk and James Cameron, and they all get dicks drawn on them), or cavort with Hat, or rock out to original songs such as “When a Man Has an Idea.” Yet the show also has a there there, one that goes beyond adding fart sound effects and cephalopod sex to Titanic. Massive piles of garbage loom (it’s not an iceberg that brings down the ship here), and Dynasty-Rose’s alternative to Hat is a gajillionaire named Dick Assenholen who’s ready to escape the climate meltdown on his dildo-shaped spaceship. He himself is also shaped like a dildo.

The show proposes no solutions, and it’s honest about the impossibility of trying to navigate our moral hellscape. At one point, a stock photo of Benjamin Guggenheim (voiced by Jibz Cameron, like everything and everyone in the show) takes Dynasty to task for crapping on the wealthy heteropatriarchy: “You have a Guggenheim grant! You wouldn’t be making this ridiculous farce of performance art without me!” Cameron’s got plenty of ambivalence, anxiety, grief, and rage to work from, but those things haven’t turned her narrow and righteous. Instead, they’ve inspired a welcoming outpouring of the pointedly absurd. It’s weirdo night. It’s the trickster spirit, which will, like roaches and pizza rats, survive the apocalypse.

.

Saturday, January 20

It’s a three-show Saturday, and I’m up bright (and cold) and early for church. By which I mean I’m on my way to exult in the 9 a.m. performance of Heather Christian’s Terce: A Practical Breviary at Irondale in Fort Greene. I’ve never seen a piece by Heather Christian that hasn’t left me cracked open, holding onto my own breath as if a pair of hands inside my chest is cupped around a small bird. Christian was reared in Mississippi with a mystical, feminist twist on southern Catholicism, and though her work now is by no means conventionally religious, it’s what I wish religion were (and what I believe, down in its deepest taproots, it’s meant to be). It’s always a happening, always a concert, always a holy act of communing — with the folks around you, with the earth underneath you, with the uncertainty and the miracle.

As a composer, musician, and performer, Christian’s got technical virtuosity, imaginative brilliance, and an unbroken umbilical cord connecting her to theater’s origins in the sacred. I file into the converted 19th-century church that houses Irondale, and the scene is already joyous: A crowd strips off coats and scarves and blinks in the blinding winter sunlight streaming from the high stained-glass windows. There are folding tables with coffee, tea, and biscuits. I run into a friend and meet his friend. Christian and her ensemble — dressed in beautifully personalized all-denim outfits, the traditional worker’s jumpsuit freed from homogeneity — move through the space, setting up chairs, checking instruments, saying hello, preparing for the service.

The show is Christian’s second experiment with the form of the Catholic mass. A breviary is a guide for prayer, and “Terce,” from the Latin for “three,” refers to the mass traditionally held by cloistered monks or nuns at 9 a.m. — three hours after the day’s first call to prayer at 6 a.m., called “Prime.” Produced by HERE as part of the Prototype Festival, Terce runs through February 4 with shows at various times of day, but there’s something undeniably special about being here at its canonical, sunlit hour.

Christian and her director, Keenan Tyler Oliphant, have been working on Terce for over a year with an ensemble of more than 30 performers — six musicians and a community choir of singers, both professional and non-, who are all either mothers or, in some form, caregivers. They’re here — we’re all here — to contemplate “the Divine Feminine.” The Terce mass, Christian tells us in a program note, “is traditionally the hour slated to address the Holy Spirit,” which, in certain texts (controversially, of course), has been referred to with a female pronoun. So, today, for all of us, whatever our gender, the Holy Spirit we address will be our “mother piece, a caretaker, a generator who can make something out of nothing.” And so we begin.

There’s nothing like music — and especially music like Christian’s — to humble and terrify someone whose job is to use words. Words render something into pieces that has shimmered in exquisite wholeness. Usually this isn’t a problem because that wholeness, that true fusion of creative strands not into a braid but into a single golden cord, doesn’t happen. But how do you describe alchemy? I can only take a deep breath and attempt to articulate some of the pieces: Christian’s inimitable voice — soaring, malleable, a thrilling tension and twang around the edges — emerging from the choir and receding back into it; the crisscrossing ropes and rigging above our heads, like a web of laundry lines, unfurling long blue sails and lowering new, homemade instruments down to the ensemble using pulleys; the live projection of Christian’s hands turning each page of the beautifully illustrated libretto; the serenity and joy in the performers’ faces. “[This] is an active ritual … we’d do it today with or without an audience,” writes Christian in her program note, and I believe her.

The choir speaks of daily work, of dirt and gardening and patience, gravity, accountability, mercy, endurance, and the myriad little objects and gestures that fill a home and make a life. “These people are not drunk, because it’s nine in the morning,” sings Christian’s cantor, and though the audience laughs, it’s practically a direct quotation from Acts 2:15. Part of the marvel of a piece like Terce is the rigor beneath its ecstatic surface. Every note, every word, is anchored, deeply rooted in a rich earth of meaning and intention even as it reaches ever upwards, toward something cosmic and ineffable. And in that rigor, there’s also humility, an infinite tenderness. “I will remind you,” sings the chorus:

You will continue to choose wrong

You will continue to be hurt

and to hurt others

I will remind you

You will continue putting yourself first

in situations, despite your mother.

And if you harden,

you’re apt to break

Turn over slowly on the ground and say tomorrow

that you are gifted with your foolishness and sorrow

You’re shedding skin

let’s go again.

Walking back out into the bright cold morning, breath once again dense and white in the air, my partner and I turn our steps toward Fort Greene Park. He was also raised in Mississippi, with various forms of southern Christianity all around him. “You know,” he said, “the verb for a mass is to celebrate. You celebrate a mass. Though it doesn’t usually feel that way.” In Terce, that spirit is still alive. “In these rough days of the spirit,” as Heather Christian’s cantor calls them, a great part of our work is to hold on to our softness — the part that cares, that allows itself to be cared for, and that longs, despite and for everything, to rejoice.

Next up, I’m back with Under the Radar for Volcano at St. Ann’s Warehouse. The show is the brainchild of director/choreographer/actor/dancer Luke Murphy, who was born in Ireland, grew up in both Ireland and Texas, and, among other things, worked with Punchdrunk for several years, originating roles in Sleep No More and The Burnt City. Murphy and fellow Punchdrunk alum Will Thompson are the only performers onstage for the duration of Volcano, and it is quite a duration, albeit ingeniously conceived. The piece bills itself as “a four-part miniseries.” Each “episode” is 45 minutes long; you get little stretch breaks between the first three and a longer intermission before the final part. In our TV-is-everything era, it’s a smart way of framing things: Four 45-minute episodes? Hell, I binged Mare of Easttown in one afternoon.

Murphy, in a director’s note, calls Volcano a “puzzle” that the audience is invited to solve, “to connect the dots … to find the meaning.” It falls neatly into what has quickly become a whole genre of contemporary drama, which I think of as Black Mirror theater. Like the anthology series, these plays are responses to the anxieties, pressures, and terrors of the technological age. They’re often nightmarish, sinister, or enigmatic; they dabble in sci-fi (or dive right in); they flirt with surveillance and voyeurism; their reference library is often more literary and cinematic than theatrical — packed with dystopian novels, TV shows, even video games.

What’s wonderful about Volcano is that Murphy’s background — and immense skill — as a dancer suffuses the piece with a distinctive, high-voltage theatricality that is, at least for me, more richly ambiguous and more compelling than the riddle of the plot. Without spoiling too too much, Murphy and Thompson are participants in a futuristic government initiative called the “Amber Project,” which aims to send capsules of data into the far reaches of space in order to “best introduce [and] represent” humanity to who or whatever might be out there. When we meet their nameless figures, they feel like pieces in a museum diorama or animals in a zoo. The dilapidated room they inhabit is a suspended box with two glass walls and no door. Here, though they sometimes pause and blink with Beckettian bewilderment, they mostly dance.

An old-fashioned radio keeps lighting up, blaring snatches of music that send Thompson and Murphy, with Pavlovian blankness and urgency, into a series of frenetic ballets, repeated reenactments, and surreal tableaux. They boogie to disco, mosh at the club, bop to mod ’60s hits, pose grandly to Handel, and twist themselves into a pouring sweat to Benny Goodman’s “Sing, Sing, Sing.” They act out game shows and wedding toasts. Familiar images leap out of their gyrations — E.T. in the bicycle basket, the tank approaching the unknown protester in Tiananmen Square, God and Adam on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Marilyn Monroe coyly holding down her skirt.

It’s possible, as the clues stack up, to assemble the pieces of the narrative puzzle, and it’s fun enough, but it’s not the production’s real strength. There’s a formula to Volcano’s content but a real explosiveness to its form, which asks us to witness two bodies enduring for almost four hours — gliding and straining, sharing weight and rhythm, flickering like TV channels from Gene Kelly charm to posturing Jerome Robbins masculinity to animal desperation and exhaustion. Inside a different container, Murphy is exploring many of the same things as the creators of Chornobyldorf. Both shows are interested in questions of cultural memory, legacy, and nostalgia — or, to put it less sentimentally, the rag-and-bone pile of humanity. Implicit in both is the question of what of us, if anything, will outlive us? And should anything?

Memory, legacy, and nostalgia haunt many, many plays these days. We joke cynically (and fret earnestly) about living in the end-times. Imagining a future — at least, a kinder one — can feel almost impossible, and so we spend a lot of time looking back. It’s the human impulse, or at least the human tradition, when things big or small pass away, and it’s also what’s happening in Hubris Always Gets You in the End.

This is my last show on this long, ruminative Saturday, and it may be — though I hope not — the last hurrah for the theater company Banana Bag & Bodice. In 2011, a younger me stumbled into a show called Beowulf: A Thousand Years of Baggage at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. I had never heard of its composer, Dave Malloy, or the delightfully named company behind its creation — it just sounded, well, badass.

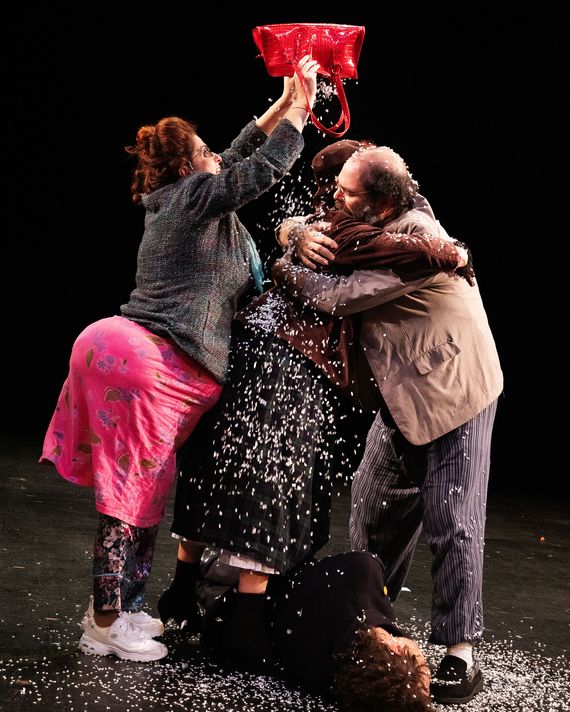

It was. (That same Edinburgh Fringe also introduced me to Rachel Chavkin and the TEAM, whose incredible Mission Drift was composed by another name that was then new to me: Heather Christian. It was a big year.) Beowulf was BB&B’s big breakout, though the project’s founders, Jessica Jelliffe and Jason Craig, had been making work together for years at that point. Now married, Jelliffe and Craig live in the Hudson Valley with their 11-year-old kid, raising chickens and attending high-school productions of Les Misérables. Hubris finds them in silly, lumpy clown costumes, surrounded by piles of their old props and memorabilia in the gutsy cinder-block box that is the Doxsee. With the help of their real-life neighbor, Feff Zezza — a musician who also “had a kid and moved” — they’re looking back on the stuff they’ve made together and asking the scariest question an artist can ask: Is this … it?

Hubris isn’t a long or super-complex show, but there’s an abundance of sly poignancy within its simple frame. The heartache sneaks up on you, because sometimes Craig is waving a massive papier-mâché severed arm and howling Beowulf bops into a microphone, or Zezza is making a BLT and waxing philosophical about the metaphor of the sandwich (he cooks the bacon on a hot plate, and we smell it for the rest of the show), or Jelliffe and Craig are slapping each other with banana peels and giggling. But also: Here are two grown-ups running around in clown suits doing all of the above, and their 11-year-old is sitting in the front row, and he’s brought friends, and they’re clearly all into it, and I can’t help feeling like that’s maybe the best thing? “It’s selfish of you to say you’ve had writer’s block for seven years,” says Jelliffe to Craig at the climax of the show’s conflict (he’s had enough, she wants to forge ahead): “You’re forgetting all the things we did in those seven years. We built a theater in our backyard. We did plays with our neighbors …” They raised chickens. They raised a human.

Whether or not this is Banana Bag & Bodice’s last show, what they’re articulating here is the heart-cry of so many artists — working day jobs and raising kids or worrying that they can’t afford to raise kids and scrabbling to put up something beautiful in a cinder-block box and hustling to get people to come and wondering if it matters and wondering if there will be a next one and fighting off bitterness and checking their bank-account balances and applying for grants and getting older and not getting famous and knowing fame isn’t the point and struggling to remember the point and just trying to find the time and the space and the means to do the thing they were meant and made to do.

But Jelliffe is right: Living matters. The daily choices matter. And the work matters — all of it, especially in the high school and the backyard and the cinder-block box.

.

Sunday, January 21

Oh, y’all, it’s the last day: the end of the Under the Radar and Prototype Festivals (though you can still catch some Exponential Fest shows through the 28th, along with a collection of new short plays in The Fire This Time Festival at the Wild Project through the end of the month).

Today, I’m headed to Theater for a New Audience to see the transfer of Shayok Misha Chowdhury’s Public Obscenities, which premiered last year at Soho Rep, where it won the Drama Desk Ensemble Award. But, though the show is participating in UTR, it’s running through mid-February, and I’m writing about it separately outside this diary. [Ed. note: Here it is — I take it back about subtlety being dead.] So, let’s do the time warp to 8 p.m.: Now I’m at BRIC for The Eagle and the Tortoise, written and directed by the film and performance artist sister sylvester.

Meditative and fascinating, sylvester’s show is a quiet communal exploration wrapped around a central core of sorrowful outrage. It takes on the Kurdish rebellion in Turkey, the Turkish government’s labeling of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (the PKK) as a terrorist group, and the U.S.’s shameful participation in the conflict. (The short version: We sold $7 million in bombs to Erdoğan’s right-wing government while also promising the PKK we’d help them in their fight for liberation if they attacked ISIL for us. Then we reneged.) It also zooms in and out — playing on the idea of both bird’s- and tortoise’s-eye views — to look at the ways in which Turkey has literally altered its own landscape in order to crush dissent: creating lakes by flooding towns; destroying and rebuilding cities to make them more uniform and receptive to surveillance technology; leveling needed agricultural areas to plant water-sucking, quick-growing pine trees to be used in government development projects; downgrading the status of the Euphrates River to a “stream” in certain places so that it can more easily be dammed, diverted, and built over. Sylvester sits behind the audience in the small, dark room we inhabit, her calm, almost soporific disembodied voice listing the appalling details. “City planning as an act of war,” she says.

The Eagle and the Tortoise is wonderfully tactile: The audience is gathered to read a book. We each get a headlamp and a beautifully constructed art book. Its pages unfold in strange, intricate ways, and as sylvester guides us through its chapters — which touch on Aeschylus, Brecht, and Murray Bookchin — we’re also listening to a musician, Ozan Aksoy, play a lulling, melancholy melody on the Turkish saz. And we’re watching a series of film clips and cinematic images on a screen in front of us, partly generated by a third performer who’s got a live-feed camera and an overhead projector focused on a table covered in artifacts and maps. The room is a cave, our headlamps like little stars — all our senses feel somehow both heightened and softened as we receive sylvester’s complex, contemplative story.

It’s a hard, sad tale — really, a dispassionate collection of facts — delivered gently, curiously, with a critical eye on both its subject and its teller. Sylvester is only a voice during the show, but we can feel her questioning her own moments of naïveté, complicity, and impotence. We are invited to do the same, and, in both its scope and its fine detail, there’s a great deal of thoughtful beauty in the invitation.

.

Tuesday, January 23

And now, for a not-over-sugary dessert, it’s Krymov Lab NYC’s Pushkin “Eugene Onegin” in Our Own Words. I was scheduled to see this last week, but my body momentarily gave out. Fortunately, though the show participated in Under the Radar, director Dmitry Krymov’s singular take on the most beloved Russian book by the most beloved Russian writer is still playing at BRIC through January 28.

I have in fact seen this Onegin before — in September, when, under the umbrella title Big Trip, Krymov’s NYC ensemble gave the piece its U.S. premiere in rep with a new show drawn from snatches of Hemingway and Eugene O’Neill. Dima is an artist I’ve been following for almost ten years, ever since meeting him in grad school. In what was quite literally a different world, I visited Moscow and St. Petersburg in the fall of 2015 — among other things, I wanted to spend as much time as I could at what was then his company’s theater.

That was back when he had so many shows running in Moscow that, according to my predecessor Helen Shaw — who wrote beautifully about Dima and his work last fall — “he would sometimes lose track.” Now, like so many who have spoken against Putin, he’s living in exile. Still, Dima’s work is always about two things: One of them is theater, and the other one is Russia. Using canonical literature — usually Russian but not always — as a trampoline, and adding the refractive mirror of his own biography, along with a lo-fi, endlessly inventive palette of design materials, he crafts shape-shifting, porous playgrounds for actors. These are plays as games, as three-dimensional sketches being dashed out, erased, and redrawn in real time, always reflecting on the soul of his home country and on the soul of the theatrical form.

So, if you’re looking for a straightforward telling of the classic verse tragedy of aristocratic ennui, spurned love, and best-friendicide, you’ll have to keep looking. The In Our Own Words part of this Onegin’s title is the most important. Krymov tucks the story of Pushkin’s protagonist inside the frame of four frumpy, eccentric Russian immigrants who have arrived in this theater, moth-eaten suitcases and stuffed Ikea bags in tow, determined to tell us one of their country’s most famous tales. Actually, they’re trying to introduce the story to children — and by “children,” I mean the marvelous assortment of dolls, assembled out of crafty scraps, that are entrusted to the audience as young charges for the viewing of the show. Mine was named Igor. He had button eyes and a giraffe onesie.

As the gaggle of dogged storytellers, Elizabeth Stahlmann, Jeremy Radin, Anya Zicer, and the young Tom Waits–channeling Jackson Scott are a fantastic bunch of serious clowns, all highly skilled at the kind of loose, responsive agility that Krymov’s work demands. In his rehearsals, it can often feel like he’s generating a script on the spot, with the actors observing him closely, osmosing his inflections and gestures while still retaining a great deal of freedom. Onegin requires acrobatic flair and sharp comic instincts, yet there is real heartbreak in the show, too: As the rejected Tatyana, Stahlmann fills the play’s longest stretch of Pushkin’s actual poetry with the heavy pathos of disillusionment and loss. There’s also an effort to address the question of art’s utility — even, in specific cases, its moral rightness in such a brutally violent world. Early in the play, an actor plant (played by Kwesiu Jones) jumps up in the audience, enraged: “You should be ashamed of yourselves!” he rails at the performers. “You can’t hide behind your beautiful Russian culture anymore. Your culture brings death and destruction!” He throws tomatoes at Radin and exits the theater on the verge of tears.

It’s a choice that clearly comes from a sincere place — a place of wrestling with one’s own identity and culpability in the torrent of the world’s horrors — but it’s the weakest in the production. Jones’s rant feels tacked on, and while it’s not disingenuous, its clunkiness pushes it in that direction. Krymov doesn’t need to apologize, especially so heavy-handedly. The work is already its own exegesis and its own self-interrogation. Like the feather that Radin produces from his pocket, which the actors struggle to keep aloft — all stumbling around and puffing at it from underneath — Krymov’s theater, in its truest form, is astonishingly light and yet full of gravity. It floats heavenwards while understanding, even celebrating, its own, and our own, ephemerality.

.

Epilogue

In 18 days, I’ve seen 26 shows, and it’s been intense but truly invigorating. So much of what I’ve seen has given me hope. So many artists are experimenting, either implicitly or explicitly, with ritual, with theater as a sacred gathering space, or as a silly, wild, subversive one — theater as a wake, as a riot, as a mass, as a coming-out party, a game, a gift, an act of archaeological investigation, an act of love.

All of these things require our presence. We’ve got to leave the house, brave the cold, ride the subway — we’ve got to show up. There is no virtual substitute. And bodies sharing space and time together mean something. In the fall of 2020, my partner and I rode bicycles across the country, from Virginia Beach to Florence, Oregon. There were certain places where, from inside the tinted windows of their huge, glossy black trucks, people were clearly angry at us — for taking up a tiny strip of road, for being weird city kids, for traveling through their territory exposed and vulnerable, which I suppose is a kind of defiance. We got honked at, we got forced to the side of the road, we got coal-rolled. But when we met people outside their vehicles — at gas stations, in diners, in their own backyards when we rolled up to stay with strangers we found through a long-distance-cycling couch-surfing site — they were softer. They were mostly kind, even curious. They fed us; they asked about our lives and we about theirs; they wished us well.

The point is not that any one gesture — a play, a conversation, a shared meal — suddenly changes someone’s vote, or, for that matter, the world. That’s MCU thinking: overblown, unhelpful, and — in its focus on heroism, on grand acts after which the work is done — ultimately insidiously defeatist. The point is that when they’re removed from the protection of their trucks or their screens, people are no longer their hardest, most closed selves.

Ursula Le Guin writes about how the Swampy Cree have a phrase to describe a porcupine backing into a rocky crevice: Usà puyew usu wapiw — “He goes backward, looks forward.” For the Cree, she explains, “I go backward, look forward, as the porcupine does,” is the way they begin their stories, their Once upon a time. “In order to find our roots,” writes Le Guin, “perhaps we should look for them where roots are usually found.” So much of the theater I’ve seen this month has gone digging in the dirt — has held onto, even built itself around its connection with the form’s deepest roots. It has been a practice, not a product; an event, not an object. It has gone backwards, looked forwards, inviting our full attention, our vulnerable participation in a moment of communal imagining: a rehearsal for a more humane future.