It’s a frigid evening outside Newark Symphony Hall, a 99-year-old building Brick City residents once referred to as “the Mosque.” Though the doors to tonight’s benefit concert for Gaza and Sudan won’t open for another hour, a line of frozen teens and 20-somethings stretches down Broad Street. Hijabs and keffiyehs dot the crowd. Once we enter the theater, attendees shed their jackets to reveal Palestinian flags, sweaters, and soccer jerseys. Organized by the Toronto-born Sudanese singer and poet Mustafa, the event features a wide-ranging lineup of mostly young, ascendant artists: comedian Ramy Youssef; singer-songwriters Clairo, Charlotte Day Wilson, and Faye Webster; R&B artists Omar Apollo, Nick Hakim, 070 Shake, Daniel Caesar, and 6lack; and British rapper Stormzy.

All this talent under one roof championing the cause of Gaza and Sudan feels somewhat miraculous while open support of Palestinian rights continues to face harsh backlash: Journalists and professors have lost their jobs, Muslim politicians have faced death threats, and actors have been fired from lucrative, franchise-helming roles, all for speaking out against Israel’s decadeslong occupation of Gaza. Since Hamas’s October 7 attack, which killed at least 1,200 Israelis, the Israeli Defense Forces have led a punishing invasion of the territory, where the death toll currently tops 22,000 and 1.9 million have been displaced from their homes. Meanwhile, an underreported humanitarian crisis continues to unfold in Sudan, where infighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces has led to massive displacement and death. The bold gambit of this evening is to put these two humanitarian crises in conversation. It’s indicative of a fearless emergent consciousness powered by young activists and artists both on the ground and online.

One would expect such an event to be tinged with sadness and anger. Yet Mustafa sets a more hopeful tone, noting in his opening remarks that the crowd’s prepurchased tickets and additional donations have already made a difference in helping distribute nonperishable food and medical supplies to Gaza and Sudan. He says this show is not just about providing aid: “It’s also about endurance, and we do know hopelessness is a tactic of all colonial projects. It’s important that none of us become hopeless … We are connected to every war. We are connected to every person that dies. And we are connected to every genocide.”

Each artist performs for roughly ten minutes, and the minimalist sets are powerful and largely percussionless. While Clairo plays guitar, the Palestinian American artist Hala Alyan recites lines from a poem: “I miss our country, the car radios, city of smoke and paint / I want you back and the war gone, and here instead, is the cruel opposite / Our gone homeland, the sorrys, long dead by the time anyone looks up.” Sudanese American author and poet Safia Elhillo follows suit: “To the machine: Is this what you meant by a country? This mouth crowded with teeth? This house wearing another house like a coat? This white sheet, this white flag, a shroud instead of the sun? I’m tired of the numbers. Like a bruise, they won’t stop growing.” When Caesar comes onstage, he leads fans in a full-venue sing-along of “The Best Part,” a sweetly sung earworm that in no way should be relevant to the evening’s proceedings, but it somehow feels cathartic, transformed by the gravity of the event and the emotion in the building. Later, Wilson takes a moment to reflect on being “grateful to be in a space where there’s collective understanding of good and bad,” while Mustafa reads a poem by the East Jerusalem–born writer and poet Mohammed el-Kurd. “What do you say to children for whom the Red Sea does not part?” he asks.

Before the show, I run into Sana, 25, and Maha, 29, two Sudanese women who made the trek from Manhattan. I ask Sana if she feels the country’s ongoing state of emergency has been overshadowed in the United States. Though she agrees that Gaza has received the lion’s share of attention, she sees it as a tide that raises all boats. “Many of us are Muslim and are so accustomed to negative representation in the media. It’s refreshing to see us cast in a positive light, even if it’s as victims,” she says. “All people under attack, whether in Sudan or Gaza or Ukraine, if there is an audience paying attention and fighting against oppression and suffering, it’s good for us all.” I also meet Ahmed, 14, and Mohammad, 18, two second-generation West Bank Palestinian teenagers wrapped in white-and-maroon keffiyehs. Mohammad tells me about the protests he recently attended and how diverse and unanimous in position and spirit they were: “You don’t have to be Palestinian to support Gaza; you just have to be human.”

For older attendees who recall decades of Palestinian concerns falling on deaf ears, the event is more than a concert. It’s a referendum, a moment to reflect on just how far the discourse surrounding the conflict has come in a relatively brief time. I strike up a conversation with Abe, 35, from West Orange, New Jersey, who says, “Being a Jew against the occupation since the 2000s, it can be really lonely. Friends, family. Smart people. People you love and respect. This shit comes up every few years, and it throws everything else into question. But this time … in my life … ” He looks around, glassy-eyed. “In my life, I never thought I’d see this,” referring to a new generation’s embrace of the Palestinian cause.

Toward the end of the evening, two Palestinian performers, Elyanna, a singer born in Nazareth, and Abdel Rahman al-Shantti, a 15-year-old Gazan who goes by the name MC Abdul, provide the evening’s most compelling moments. During her set, Elyanna ululates, wailing traditional Arabic sounds and rhythms conjugated into world hip-hop. MC Abdul — whose music videos showing him rapping in front of rubble went viral in 2020 — stalks the stage in a chunky letterman jacket with a Palestinian flag; beneath it, in black-outlined silver block letters, reads, “WE ARE HUMAN TOO.”

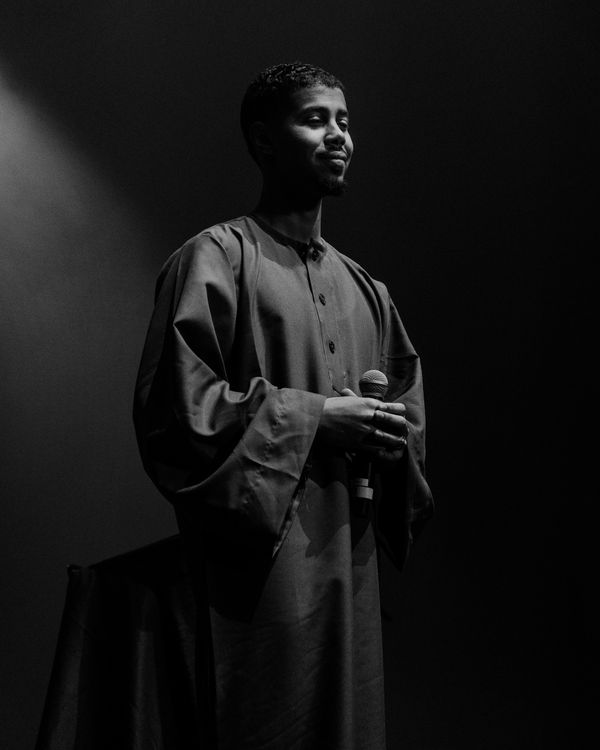

Youssef closes the show echoing the jacket and the sentiments of the young, unapologetic Arabic crowd Abdul represents. Youssef is of a generation of Muslims traumatized by 9/11 and the conversation it created around his religion and identity in this country. The way the attacks normalized Islamophobia in America is a topic he has pursued throughout his comedy, perhaps most significantly reenacted in an episode of his eponymous TV series. In his brief, powerful set here, he encapsulates the evening’s spirit of embrace. He sounds ready to leave the baggage and self-recrimination of that work behind him: “That’s the thing about Muslims. We persevere. I wish people could see the beauty in this room.” Youssef gestures around the hall at the people who have gathered here to grieve but also to heal from their respective traumas; to attempt to contribute something, anything to an impossibly large and distant ongoing tragedy; and no longer resign themselves to suffering silently. Youssef concludes, “And that’s why, seeing all these artists come in, everyone has a different background, but we all know the truth. We share that. And I think we’re all in this spotlight now. As a Muslim? I’m done apologizing … I’m tired of them dehumanizing us. And yeah, I’m done. I’m done doing it.”