The first time I read the word Aack! was in the global syndication of the daily comic strip “Cathy,” nestled between “Garfield” and “The Far Side” in the English-language newspapers in Malaysia, where I grew up. I lived half a world away from the creator of “Cathy,” Cathy Guisewite, but the main character’s catchphrase imprinted itself onto my brain anyway — a testament to the strip’s power in the ’80s and ’90s. “Cathy” is now typically evoked with mixed feelings, denigrated for what it is half-remembered to represent: the angst of a distinctly boomerish upper-middle-class white woman exasperated by her attempts to “have it all” (a man, a white-collar job, a body that fits with conventional beauty standards) and wracked with guilt about the whole thing. The comic ran in newspapers for 34 industrious years, from 1976 to 2010, and its brand of fame adds to the complication: Surely, anything beloved by so many suburban, middle-aged moms must be antithetical to good taste.

Jamie Loftus does not believe this. And in Aack Cast, the audio series that debuted last month, she mounts a full-throated argument for “Cathy” and its complexity. To see it, she posits, you just have to take the strip’s whole context on its own terms — the character, the time frame, Guisewite herself. You also have to, you know, actually read the comics. (And Loftus has read all of them.) Through a mix of interviews, literary analysis, and opinion, Aack Cast pays close attention to how the title character navigated the fluid mores of an accelerating culture. When confronted with the changes of the comic strip’s many eras — by Loftus’s accounting, it spanned seven presidents and two feminist movements — Guisewite’s creation often seems circumspect, uncertain how she feels about the new things being asked of her. Cathy is a figure defined by figuring stuff out.

Oh, and there’s this: “While it’s never shown in the comics, obviously, Cathy fucks,” Loftus emphasizes in the first episode, checking off a list of men who appear as the character’s boyfriends. “She fucks, and to think that she only dreams of fucking but never does is to fundamentally misunderstand Cathy.”

Loftus is a singular voice in podcasting: messy yet precise, confident yet conflicted. Also, very funny. The comedian and TV writer turned to audio several years ago and, recently, has become a model for what a truly independent voice in the medium can sound like. (Her first solo audio project was 2020’s My Year in Mensa, in which she documents her strange journey of becoming a member and, soon after, persona non grata of the self-described high-IQ society.) Aack Cast — which she created with support from and distribution by iHeartMedia — is her third longform audio project in about a year and a half. It follows Lolita Podcast, which she released last fall and which revisited the controversial legacy of Nabokov’s 1955 novel, and the two podcasts could be considered companion projects: both unorthodox feats of cultural journalism, about artifacts intimately connected to mainstream ideas regarding women and womanhood. (Loftus also co-hosts the weekly The Bechdel Cast with Caitlin Durante, exploring the portrayal of women in film.)

All of Loftus’s skill sets are detectable in Aack Cast, which is currently slated to run for eight episodes: She stitches together archival and interview tape with sketchlike re-creations of the comics and her own narration, drifting among reporting, personal essay, and jokes. The strip’s tentativeness about leaning hard into feminist ideals and the character’s obsession with her weight can be read as conservative, almost regressive. But Loftus has enormous empathy for the character, and that makes up the backbone of the podcast’s philosophy. “I think Cathy is a symbol of how women’s anxieties and concerns can be considered embarrassing, or not worthy of discussion, if the character in question isn’t a perfect model,” she says.

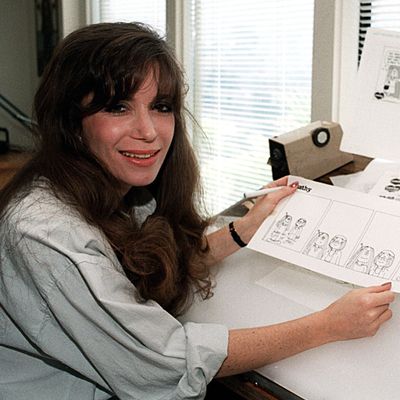

She extends that assessment to Cathy’s creator too. As Loftus makes clear, Cathy Guisewite the person is not Cathy the character. Guisewite didn’t even want to name the strip after herself. (It was her syndicate’s idea.) But as the second episode highlights, the challenges that Cathy faces are about the same ones that Guisewite confronted in her own life — the emotional morass of food and body image, the struggle between self–definition and an obsession with men. Guisewite started the strip when she was in her 20s and became a minor celebrity during the comic’s high-water-mark years — we’re talking a global-merchandising empire and appearances on Johnny Carson. Like Cathy, she is subject to her own evolutions. Talking to Loftus about an early interview in which Guisewite had said, “No matter what a woman does, having a man in her life is the most important thing,” the Guisewite of today admits, “I read that now … It’s truly like reading your diary. You just want to throw up. Or burn it.”

Even as Loftus argues for Cathy and Guisewite’s relevance, though, she remains alive to critiques — mostly, critiques about the fact that the comic only shows a specific slice of female experience. The strip broke through during an era when the medium was completely dominated by male cartoonists, with female perspectives virtually nonexistent. But perspectives like Guisewite’s take up a lot more space today. Loftus insists on complexity, placing a strong emphasis on how we’re always negotiating the politics of the moment, our own perspective, and the hand we’re dealt. A position of relative privilege doesn’t necessarily cancel out the pains you may feel. Both things can be true at the same time.

A huge part of what’s appealing about Loftus’s longform audio projects is how personal they seem to her. Between delivering her arguments and findings, Loftus periodically dips into her own life, refracting her insecurities and uncertainties into the analysis. She takes that approach whether the subject is “Cathy,” Lolita, or even Mensa. In the Mensa series, you could hear her excoriating the group’s toxic culture and its very concept. But you could also hear how she is affected by the Mensans’ treatment of her—how it flares up her insecurities about being a person in the world. In that sense, Cathy and Loftus are kindred spirits. At the end of the day, they’re both just trying to figure stuff out. Aren’t we all?