When Abby Hanlon was publishing her first childrenÔÇÖs book, Ralph Tells a Story, she got a note from the art director: The teeth on her drawings were too pointy. The characters looked like vampires and elves rather than kids. So Hanlon went about rounding the teeth and ears. After she handed in the book, she found herself doodling vampires and elves. If her drawings already looked too elfin, she might as well go with it. Meanwhile, at home, her own children, 5-year-old twins, were growing obsessed with GrimmÔÇÖs Fairy Tales. ÔÇ£They wanted to read the gruesome ones. They liked being scared,ÔÇØ she says, slouched on a beanbag chair in the backyard shed, barely wider than a desk, that serves as her writing studio in Park Slope. Her daughter became infatuated with Mrs. Hannigan, the cruel orphanage headmistress in Annie. ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs how I started thinking about Mrs. Gobble Gracker,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£Just them gravitating toward the dark and scary and needing that.ÔÇØ

Mrs. Gobble Gracker is the imaginary villain in what would become Dory Fantasmagory, HanlonÔÇÖs chapter-book series. She is a 507-year-old woman who drinks coffee and wants to steal Dory, age 6, and make her her baby. She has a tight headmistress bun, a witchy black dress and cape, and, yes, sharp teeth. Mrs. Gobble Gracker herself is an invention of DoryÔÇÖs older brother and sister, Luke and Violet, who hope to scare Dory into acting more mature. The plan backfires. Instead, Dory decides Mrs. Gobble Gracker is the best game ever, much to the annoyance of her siblings and everyone else. That a criticism ÔÇö Your drawings donÔÇÖt look right! YouÔÇÖre acting like a baby! ÔÇö can become creative fuel, lit by the real, wacky, often dark imaginations of children, is a lesson at the heart of the series and a pretty decent description of HanlonÔÇÖs own creative process.

Since she started writing the Dory Fantasmagory series in 2012 (the sixth book, Dory Fantasmagory: CanÔÇÖt Live Without You, will be published on September 26), it has been translated into 25 languages, selling 1.5 million copies. The popularity of the series grew slowly, and not until the fourth book did she earn her first review in the New York Times. It has since become the kind librarians and elementary-school teachers eagerly foist on early readers and their parents. ThatÔÇÖs in part because the series is a unicorn of childrenÔÇÖs literature: chapter books geared toward new readers that are a pleasure even on the hundredth read, largely because theyÔÇÖre funny ÔÇö the kind of funny that comes from being wholly recognizable. For children, DoryÔÇÖs antics and worries ÔÇö If I tell the truth, IÔÇÖll get in more trouble. If she knows how weird I am, she wonÔÇÖt be my friend ÔÇö are deeply familiar, and for parents, reading the books can illuminate their own kidsÔÇÖ misbehavior and even bring on some needed empathy. Dory has hints of Ramona Quimby and Calvin of ÔÇ£Calvin and Hobbes.ÔÇØ Hanlon also cites as an influence Kevin Henkes, whose mouse books (Chrysthanthmum, Sheila Rae) are deeply attuned to childrenÔÇÖs emotional lives. None of these quite scratch the same itch as Dory, though.

From the beginning, the books have embraced the uglier parts of childhood and of raising children. Hanlon knows kids have weird little minds: They say uncomfortable, unpleasant things. Their humor skews scatological. They throw tantrums and annoy their siblings. Hanlon was a New York City schoolteacher before she was a childrenÔÇÖs-book writer, and she learned this lesson from teaching and from raising her own two children. Her greater insight was to see that children do many of these annoying things not because theyÔÇÖre bad but because they are often following the logic of a game. Dory pretends to be a dog and drags a toaster into her room because thatÔÇÖs what the game calls for. ÔÇ£My guiding force,ÔÇØ Hanlon says, ÔÇ£has been, How do I make a book thatÔÇÖs reflecting kidsÔÇÖ imaginations and not mine?ÔÇØ

Hanlon became a teacher not long after graduating from Barnard in 1998, through the city teaching-fellows program ÔÇö sort of a local version of Teach for America ÔÇö and she eventually earned a masterÔÇÖs. Her first teaching job was in Harlem, where she stayed for two years. After being ÔÇ£excessedÔÇØ (ÔÇ£The school was failing, and I was last in and first outÔÇØ), she taught first grade at P.S. 107 in Park Slope. The curriculum there encouraged students to take the small events of their lives ÔÇö a trip to the beach, a fight with a sibling ÔÇö and turn them into a story. ÔÇ£It showed them their little experiences had value,ÔÇØ Hanlon says. She would write her own stories, complete with stick-figure art, as examples for the class.

One day, a parent came up to her after school and told her he was a childrenÔÇÖs-book agent. ÔÇ£He just kind of paused, like waiting for my reaction or my ÔÇÿWow,ÔÇÖÔÇØ she says. She was sure he had recognized her talent and was about to tell her she was meant to be a childrenÔÇÖs-book author. That wasnÔÇÖt what he was trying to tell her at all. ÔÇ£He was trying to tell me he could get me free books for the classroom.ÔÇØ

Still, she went home from school that day and decided to write a childrenÔÇÖs book. ÔÇ£I never draw, I had no background at all,ÔÇØ she says, ÔÇ£but I couldnÔÇÖt think of a story without also thinking of the pictures.ÔÇØ So she started to teach herself how to draw. She bought a copy of Make a World, by Ed Emberley, which breaks drawing down into its geometric elements ÔÇö in other words, a half-step up from stick figures. When she finished her manuscript, about an imaginative kid sort of like Dory, she sent it to five book agents, including, once the school year ended, the agent dad from her class, who took months to get back to her. (ÔÇ£He was not impressed.ÔÇØ) Only one of the five responded with encouragement, a veteran named Ann Tobias, who told her she could see Hanlon had a keen understanding of children but didnÔÇÖt yet have the drawing skills. She told Hanlon to take a drawing class and to send her an example of her work once sheÔÇÖd gotten better at it. ÔÇ£She didnÔÇÖt want to give me her email, so we just communicated by postcard,ÔÇØ Hanlon adds.

After three years of sending postcards of illustrations, Tobias agreed to work with her on a new story about a boy who canÔÇÖt think of anything to write during writing time in school. The plot mirrors the lesson of the class Hanlon had been teaching ÔÇö that the small moment is its own exciting story. That became Ralph Tells a Story, and its brilliance is that it never feels like vegetables to kids. RalphÔÇÖs struggle is real life for them, where the biggest challenge of the day may very well be that writing is boring and hard and it feels like nothing happens worth writing about. All the little moments in the story are hilariously specific. ThereÔÇÖs the one kid in class whose stories go on forever on long scrolls of paper; there are the kids who have 5 million questions for Ralph on the inchworm he writes about, questions no adult would ever think of asking. The book has kid brain.

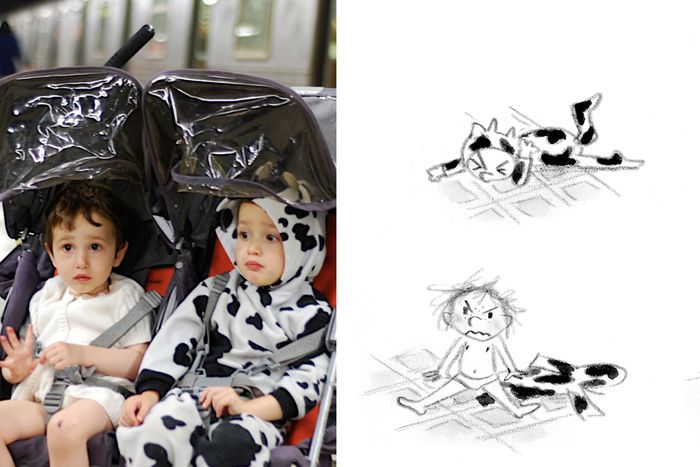

By the time she started working on her next project, the Dory series, Hanlon was no longer in the classroom, but she had something better: two 5-year-old in-home consultants. She would park herself within earshot and take dictation while they played. ÔÇ£Kids are easy to study because theyÔÇÖre not holding back what theyÔÇÖre thinking,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£TheyÔÇÖre constantly telling you how they feel. They shared a room, and after they went to bed, I would listen to them talking to each other.ÔÇØ The Dory books became a secret document of their childhood filled with private jokes. Like the cow costume Dory refuses to take off in book one. ÔÇ£My son was wearing a cow costume from Halloween until May or June,ÔÇØ Hanlon recalls. ÔÇ£HeÔÇÖd be on the subway platform sweating and wouldnÔÇÖt take it off.ÔÇØ Her son also inspired DoryÔÇÖs turn as a dog, a game she wonÔÇÖt give up even at the pediatricianÔÇÖs office, to her motherÔÇÖs deep, boiling frustration. Her children eventually became not just her inspiration but her co-writers. It was the twins who suggested Mrs. Gobble Gracker drink coffee ÔÇö Hanlon had originally had her drinking blood.

The action of the Dory books is almost entirely driven by the games she plays and the unintentional ways those games intersect with her real life. Through those games, Dory learns how to navigate her world: how to get along with her siblings, make friends, deal with disappointment. She struggles to learn to read, while she imagines that a little black sheep named Goblin has escaped from her book. SheÔÇÖs anxious about losing her first tooth and growing up, but sheÔÇÖs also trying to rescue the Tooth Fairy, who has been kidnapped by Mrs. Gobble Gracker. ÔÇ£Kids learn through playing, and they process their emotions and experiences by acting it out and pretending to be someone else,ÔÇØ says Hanlon.

Hanlon knew from the beginning that she wanted Dory Fantasmagory to be a chapter book, but publishers thought there was a disconnect between DoryÔÇÖs age and the format. Ten years ago, you didnÔÇÖt typically have chapter books about 6-year-olds because publishers didnÔÇÖt believe 6-year-olds wanted to read chapter books. Hanlon knew this wasnÔÇÖt true. Six-year-olds might still need pictures on every page to stay engaged, but there were plenty who wanted to read (or have read to them) substantial stories. ÔÇ£Kids always want to read like older kids,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs what gives them currency.ÔÇØ

The publishers who didnÔÇÖt reject it for being a chapter book rejected it because there was no plot. ÔÇ£It was little vignettes,ÔÇØ she says. So Hanlon went about teaching herself narrative arc, some of which she picked up from the creators of South Park. ÔÇ£They had this little video where they write a South Park episode. They just write ÔÇÿbut therefore, but thereforeÔÇÖ and then fill in the plot points between it.ÔÇØ The unintended consequence of each action leads to the next action. From her editor, she learned that if you can take out one part of the story and put it somewhere else, then you havenÔÇÖt built the arc correctly. Those two realizations unlocked the book, and eventually Penguin bought it. Dory Fantasmagory came out when HanlonÔÇÖs twins were in first grade. It was the first chapter book they read on their own.

ThereÔÇÖs something deeply familiar in Dory. Talk about her with other parents and youÔÇÖll often hear someone confess that their youngest (itÔÇÖs usually their youngest) is ÔÇ£such a DoryÔÇØ ÔÇö committed to their imaginary world to the point of unruliness. More than one parent I know has mentioned their child spent a prolonged period pretending to be a dog. I caught myself laughing in recognition in book six when Dory covets her sisterÔÇÖs ChapStick. (What is it about ChapStick? Why do they want it so badly?) And unlike the popular TV series Bluey, in which the kids also have roving imaginations, the parents in Dory Fantasmagory react much the way real parents do, able to handle the game for only so long before they really need Dory to put on her shoes or sit at the table. When I read them to my children, we laugh at both Dory and her mom, who is usually saying (yelling?) things that have also come out of my mouth.

For all the parents who saw their own children reflected in Dory and smiled, there were some who saw DoryÔÇÖs antics and bristled. She does a lot of annoying things you wouldnÔÇÖt want your child to start doing. ThereÔÇÖs some occasional potty talk, some flinging around of the word stupid. If you are the kind of parent who wants to pretend the world does not contain these concepts, or who has taught their kid (as we did) that the S-word is stupid (we got away with this until our daughter was at least 6), then the Dory books can present a problem and a gentle challenge: Are you parenting real or imaginary kids? How much should books reflect the world as you want it to be or the actual world they live in?

I admit I also bristled. The first book we picked up, at the recommendation of a librarian, was from the middle of the series; in it, DoryÔÇÖs friend Rosabelle loses it with her younger brother. She calls him a ÔÇ£nosy beastÔÇØ and a ÔÇ£butt babyÔÇØ and attacks him before Dory helps him escape by stuffing him into a laundry hamper. My oldest child was maybe 5 at the time, and her younger brother was still a baby. Did I really want her walking around the house saying ÔÇ£butt babyÔÇØ? Today, that baby brother is about DoryÔÇÖs age, and when we read that scene together, we all laugh hysterically, cathartically, before they go back to fighting about whoÔÇÖs taking up more room on the couch and who canÔÇÖt see because the other one is in the way.

Hanlon realizes now that the parents who react negatively to Dory, who donÔÇÖt see the humor in it, are not really her people: ÔÇ£If you met me, you would not like me, you would not like my kids, you would not like my parenting.ÔÇØ She has also become more attuned to whatÔÇÖs considered inbounds for childrenÔÇÖs literature. ÔÇ£In the beginning, I didnÔÇÖt realize stupid was a bad word,ÔÇØ she says. Her longtime editor retired after book five, and her editor for book six, Jessica Garrison, is a mother of young children and is more sensitive to the language in the books. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve wondered as we reprint those stories if itÔÇÖs a thing where we change stupid to silly,ÔÇØ Garrison says. ÔÇ£I think a lot of parents sub in silly for stupid as they read aloud. WeÔÇÖre all just a little bit more caring and mindful about how weÔÇÖre using words now.ÔÇØ For the new book, in which Krazy Glue figures prominently, she and Hanlon discussed how to use the word crazy to advance the story without being overly indulgent.

The new book centers on separation anxiety. Dory gets momentarily lost in the hardware store and after eavesdropping on some teenagers learns that Mozart isnÔÇÖt alive. (Another plot point taken from HanlonÔÇÖs own children: ÔÇ£My kids both cried about Mozart. They were like, ÔÇÿWe wanna see Mozart.ÔÇÖ IÔÇÖm like, ÔÇÿWhat? HeÔÇÖs dead.ÔÇÖ They were 3.ÔÇØ) Soon after, DoryÔÇÖs mother informs the family sheÔÇÖs going back to work. These events send Dory into a tornado of worry that her mother will abandon her forever. To quell her anxiety, DoryÔÇÖs mother gives her a locket with a picture of her as a teenager inside. Dory loves it. ÔÇ£If you die, IÔÇÖm going to trap your ghost inside my locket,ÔÇØ she tells her mother. Later, she iterates on the idea: ÔÇ£Maybe I can put one of MomÔÇÖs body parts in my locket. So she can always be with me,ÔÇØ she tells Luke and Violet. ÔÇ£I might have to put a special oil on it so it doesnÔÇÖt rot.ÔÇØ ÔÇ£My daughter actually said that,ÔÇØ says Hanlon. In real life, though, Lulu kept going: ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm going to ask my daughter to put it in my grave when I die so I can always keep your body with me. ThatÔÇÖs how I can always keep your heart inside my body.ÔÇØ

Hanlon was a little surprised the death theme made it past the editors. ÔÇ£I sold this to them as about separation anxiety, and I didnÔÇÖt mention death because I didnÔÇÖt know how that was gonna go over. But I also wanted to push for this death thing because kids talk about it,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£These kids just lived through a pandemic. What is the pandemic if not about that?ÔÇØ (She didnÔÇÖt need to worry. ÔÇ£Absolutely loved it,ÔÇØ Garrison said about the death theme. ÔÇ£I had fielded the same questions from my 9-year-old when he was about 6.ÔÇØ)

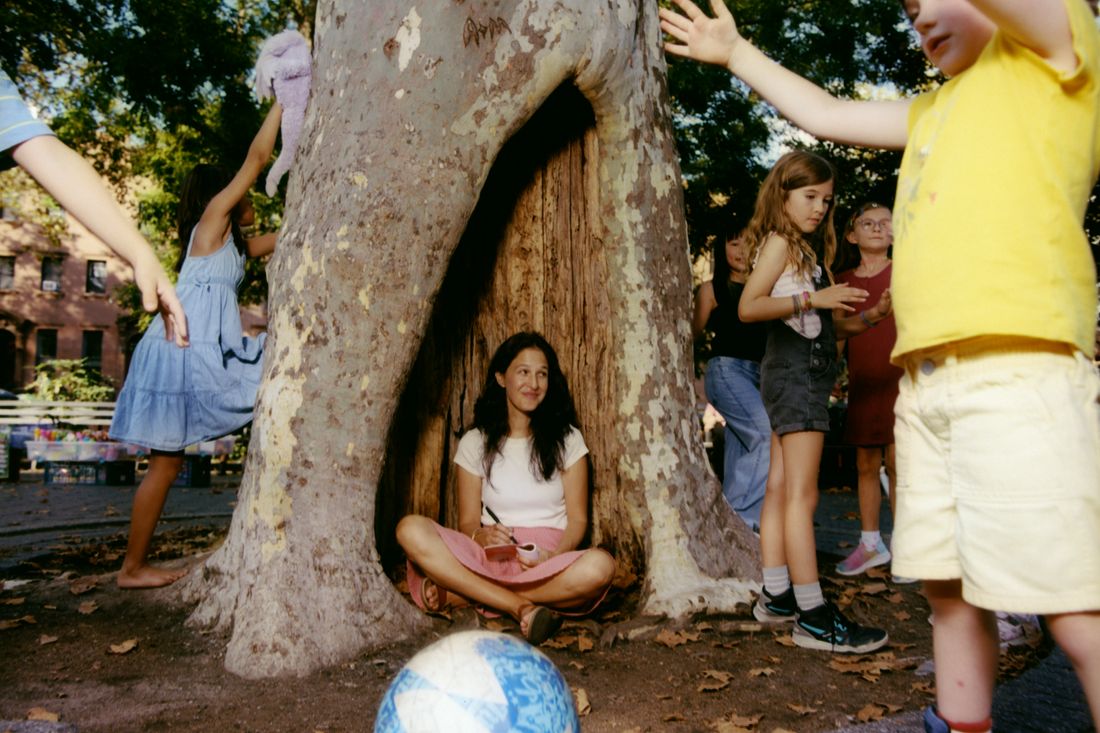

HanlonÔÇÖs twins are now 16 and no longer making pillow forts in the living room. She still has a 150-page document from those prime playing years she refers to for ideas, but lately she has been finding new ways to mine the minds of children. She listens to kids she meets at author visits and reads the letters they send her, and she has started volunteering in the kindergarten class at her kidsÔÇÖ old school. ÔÇ£I just need to hear how kids speak,ÔÇØ she says, and what theyÔÇÖre thinking about. They tend to be good at plot, too. In one recent letter, a kid told her, ÔÇ£I think Mrs. Gobble Gracker should have an older brother and older sister who are mean to her.ÔÇØ She says, ÔÇ£I was like, Oh my God. TheyÔÇÖre so smart. TheyÔÇÖre one step ahead of me.ÔÇØ

More on children's books

- ÔÇÿEvery Movie Is a Coming-of-Age MovieÔÇÖ: A Conversation About My FatherÔÇÖs Dragon

- Julio Torres Wrote a ChildrenÔÇÖs Book About a Plunger That Wants to Be a Vase

- The Very Hungry Caterpillar Author Eric Carle Has Died