This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Darren Aronofsky was just a few years out of film school, and a year off his 1998 indie phenom of a debut Pi, when he started making Requiem for a Dream. But in some ways, it was a project he’d been preparing for all his life — an adaptation of a book by his literary idol, Hubert Selby Jr., that he set in the areas of South Brooklyn where he grew up. “I guess the preproduction on this was years and years,” he said. “It was a lot of my childhood and youth.” Ellen Burstyn, who’d get an Oscar nomination for her role as Brighton Beach widow Sara Goldfarb, was the lauded veteran working with a trio of fresh-faced performers in different periods of transition. Jared Leto, who played her smack-addicted son Harry, was on the cusp of a transformation from teen television-show dreamboat to movie star. Jennifer Connelly, as Harry’s girlfriend Marion, was a former child actor navigating what’s historically been an often-fraught path toward a grown-up career. Marlon Wayans, as Harry’s best friend and partner in crime Tyrone C. Love, was a well-known comedic talent proving his capacity for drama. The 2000 feature, made just as the independent film scene was moving past a ’90s heyday toward something new, is an intersection point for many now-prominent careers — a movie made by the young.

And it feels young. The thrill of Requiem for a Dream comes from it being the work of artists who hadn’t yet been told what they could and couldn’t do, for better and, maybe in one instance, for worse. It took on uncompromisingly dark material with such an exuberant sense of style and boundless energy. Twenty years after Requiem made its debut at Cannes and tangled with the MPAA over an NC-17 rating, it remains an influential cultural milestone that continues to reverberate through different media, and an ending that still has viewers curling up in the fetal position like the characters do right before the credits roll. Aronfosky’s second feature was a formative one for a whole swathe of budding cinephiles who’d sneak a director’s-cut version of the DVD home to watch a transgressive story of addiction destroying four lives, all told in gloriously maximalist fashion, from the mini-montages of drug use to the time-lapse interludes to the famous Kronos Quartet–performed score. This is the story of Requiem for a Dream, two decades on, from the people who made it — including Aronofsky, the film’s stars, and many pivotal members of its crew.

Meeting a Literary Hero in His Underwear

Requiem for a Dream, a movie about four people whose lives are gradually destroyed by their various addictions (and the emotional voids they’re trying to fill), was based on a brutal, poetic 1978 novel by author Hubert Selby Jr., who died in 2004. Selby’s 1964 book Last Exit to Brooklyn had already been adapted into a 1989 film, one that starred Stephen Lang, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and Burt Young.

Darren Aronofsky, director: When I was a freshman in college, I was walking through the library and out of the corner of my eye, saw the word “Brooklyn.” I grew up in Brooklyn, so I pulled it out, and it was Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby, Jr. It completely blew my mind, that book, and just made me start thinking about being a storyteller.

When I got to film school in Los Angeles, they told me, “You’re going to do a bunch of short films.” Selby wrote a collection of stories called Songs of the Silent Snow, and there was one called “Fortune Cookie,” about a door-to-door salesman who can only make a sale if he has a good fortune. I was like, “Oh, I’ll adapt that.” I called the Writer’s Guild to see if I had to get permission, and the Guild gave me [Selby’s] home phone number. I called him up and he said, “Oh, come on over.”

Eric Watson, producer: My only awareness of Selby at that point was Last Exit to Brooklyn. A guy I went to high school with, Sam Rockwell, that was the first movie he had a big role in, so we all went with him to see the premiere at a small theater in San Francisco.

Aronofsky: When you read Hubert Selby, Jr. you’re expecting someone more like Henry Rollins. But he was very slight, and he was dressed in a pair of underwear. He lived in a studio, maybe a one bedroom — a small, humble thing. And he said, “Here, I’ve just been working on this translation,” and handed me a Lao Tzu poem that he had been working on arranging. He was this incredibly peaceful, gentle soul, and he gave me his blessing.

Watson: After we made Pi, we were the indie darlings of that year. Everybody was asking us, “What do you want to make next?” We met all these executives who wanted to work with us and said “anything you want to do.”

Aronofsky: There was a great book shop in Venice Beach, where I lived, that I hope is still open. Requiem for a Dream was on the shelves, and I picked it up and I started to read it, and it felt so familiar that I never finished it.

Watson: Darren and I were roommates in Hell’s Kitchen, and he had this book on the shelf called Requiem for a Dream. I asked him, “What is that?” He said, “It’s a Selby book, but I couldn’t finish it. It was just too much for me to handle.” I’m like, “Well, can I borrow it?” I took it with me on a skiing trip with my parents and grandparents and it ruined my vacation. But I read it cover to cover, and then I got back and I said, “We got to make this into a movie.”

Aronofsky: So I read it. It’s just very cinematic, the book. Images were popping off the page in my head, of how to interpret this. We went out, we found Selby, and I think we optioned it for a thousand bucks. The novel is actually set in the Bronx, and the first thing I asked him, I was like, “Look, I don’t know the Bronx at all, but I know this south part of Brooklyn where I grew up. Do you mind if I set it there?” He was like, “No.” I rented an apartment out in Sheepshead Bay, and I just started working on it.

Watson: Selby had written [a screenplay adaptation] years before. He finally found it in somebody’s attic and sent it to us and we looked at the two drafts and they were really similar.

Aronofsky: I was able to blend them a bit, but unfortunately [Selby and I] never really got to work in the same room, which would have been an amazing experience.

Watson: We sent the finished screenplay to all those people who’d said “anything you want to do.” Nobody called us back. So we learned a lesson about Hollywood — they don’t always mean what they say. But we went to Artisan, the company that had bought Pi at Sundance and kind of built their brand around our movie. They said, “Well, we believe in you guys. If you put a cast together, we’ll give you this much money.”

Aronofsky: It was still challenging. I think three weeks before we were shooting, our budget got cut by $1 million. It was very scary. I can remember getting that phone call that we lost a quarter of our money. I think I might have shed a few tears.

“This Is the Most Depressing Script I’ve Ever Read”

With a budget of around $5 million, Requiem for a Dream was a small independent production, but a considerably more expansive one than Pi, with the capacity to bring on a more established cast. The dark material — which involves heroin and amphetamine use and escalates into electroconvulsive treatment, incarceration, sexual humiliation, and amputation — posed some interesting challenges in terms of finding actors.

Watson: We engaged a casting director named Mary Vernieu, who helped get us in front of a lot of actors. And a lot of people said no to us.

Aronofsky: Pretty much everyone in the cast was not what I was aiming for at the beginning of it. I went to a lot of actors before I settled on this cast. I may have told Ellen, but I think she was fourth or fifth down the list. There were a lot of great actors that said, “No fucking way.” I had offered it to Anne Bancroft and I had a beautiful conversation with her, and she told me that it’s the first role she passed on that she had to talk to her shrink about. And I was like, “I guess that’s a compliment.”

Ellen Burstyn, Sara Goldfarb: My agent sent me the script and I read it and I called her and I said, “This is the most depressing script I’ve ever read. Who on earth is going to want to see this movie? I can’t imagine.” And she said, “Before you turn it down, there’s a little movie called Pi, you should look at.” I had never heard of it. Within the first three minutes I went, “Oh, I get it. The guy’s an artist. Okay.” So I said, all right, I’ll do it.

Darren came up to Hartford, where I was doing Long Day’s Journey Into Night, and we met after the play. He was a very young man, but I was impressed with his film. So I felt secure.

Aronofsky: I didn’t really know Jared’s work at all. So I had to really educate myself on him. And I think there were a bunch of actors I went to — the who’s who of who was hot back then — and they all passed on it.

Watson: Tobey Maguire, that was someone who said no to us.

Jared Leto, Harry Goldfarb: I remember how badly I wanted to be a part of the film and how badly I wanted to work with Darren. He made me earn it, for sure. There were multiple auditions. I knew he liked me, but he wasn’t a hundred percent, so there was a period of courtship. I remember him calling me one time. It had to have been two in the morning, and I picked up the phone and was laying in bed, and I sat there pitching myself. I wasn’t shy about it either, it wasn’t that sort of process. It was like, listen, I see the opportunity here to challenge myself in a way that I’ve never been challenged before and I know that doesn’t come around too often.

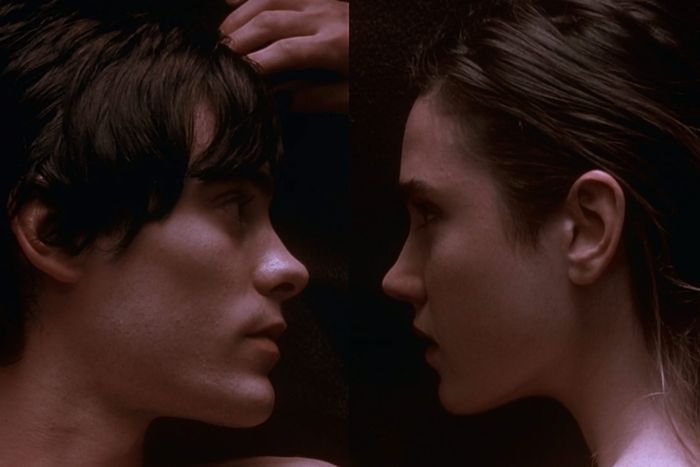

Once I got the role, I remember reading with a lot of people for other roles. Darren read with every actor in town for the part that eventually went to Jennifer.

Watson: We had a lot of actors show up for that role. We were surprised at the response that we got. We had a session where Jared was already onboard, and we had Jennifer come in, because she wanted to do the film. They hadn’t met each other. They did the scene, and she basically threw him around the room in the audition. And we were just like, wow.

Leto: I think she threw a chair across the room.

Jennifer Connelly, Marion Silver: I remember loving the script and feeling strongly about it. I found it moving. Devastating, but also really moving. I remember wanting so much to be part of it: I really want to fight for this one. And it was a bit of a fight. I think Darren wasn’t entirely convinced about the idea of me for a while.

Aronofsky: I definitely loved Jennifer’s work from Once Upon a Time in America, one of my favorite films. At the time, I don’t think her career was thriving for some reason, but she gave one of the best auditions I’ve ever seen to this day. She came in, and I was not expecting anything, and she left with the role.

Marlon Wayans, Tyrone C. Love: I started out with the script and I was like, Oh, hell no. I’m going to kill myself. And I’m a happy person. But when I look at a movie, I don’t just look at the script. If there’s a book, I read the book. If there’s a director attached, I watch the director’s work. And that’s exactly what I did. I read the script, I read the book, and as soon as I saw Pi, I knew what the movie would be.

Watson: [Wayans] had gone to the performing arts high school in New York. We knew that he had that background with him, and that capacity. And in the auditions, he was able to show a lot of range and capacity to handle dramatic scenes. We had no fear about it. We knew we’d be okay. We certainly were questioned by others [about the decision to cast him] until they saw the movie, because he wasn’t taken seriously. And he never really chose to do [drama] again, but he could have.

Wayans: It’s not that I don’t do drama. I haven’t been on the top of the list, because people don’t know if I can do drama or not. I studied drama for four years every day.

Aronofsky: I wanted to cast Dave Chappelle. I had a bunch of friends that were in the comedy scene, and I’d seen him onstage and thought he was amazing. I begged him, but he wasn’t really interested in acting at the time. So he passed. But I always felt like a comedian for that role would be great. There were so many great actors for that role that could have done it, but Marlon just came in and there was a level of commitment — I think he didn’t shower for three days.

Wayans: I slept in the same clothes, literally, for ten days. I barely washed. I would talk like the character. My boys would come over to the house — Omar Epps was concerned, like, Are you okay?

Aronofsky: We were with the casting director, and at a certain point [Wayans] leaves, and there’s this explosion, a big pop outside. Marlon was in such a daze — it was one of those lots that has those nails if you go the wrong direction, and he tore out his tires on his car. He came in and we ended up having more time together, because they were waiting for his car to get towed. The fact that he was from New York, from a neighborhood I knew well growing up — I felt that he could really connect to the character.

Christopher McDonald, Tappy Tibbons: I auditioned with Mary Vernieu in a room, and she sent that off to Darren, and Darren said, “He’s our guy.” I went to his little apartment in Midtown, and we went up on the roof and he said, “I’m gonna ask a few questions.” I ad-libbed all this stuff about Tappy Tibbons, just crazy stuff. I was channeling Tony Robbins, walking down the street, talking to people. Some people knew me but didn’t know my name. And I said, “Yeah, I’m Tappy Tibbons, you’ve seen me on TV” — just stopping random people in the streets and making up, like, “30 days, it’ll change your life.” I just riffed on it, and then [Aronofsky] did use a lot of it in the movie.

Going Super Method

There was an unusual amount of rehearsal time built into the Requiem for a Dream schedule — enough for the actors, who’d come from different backgrounds in television, film, and comedy, to spend a few weeks together and separately preparing. This meant fleshing out some of the relationships between the characters — the young, naïve romance between Harry and Marion, an aspiring fashion designer, and the friendship between Harry and Tyrone, who start dealing drugs in addition to using them.

Aronofksy: All of the younger actors got there a month before or something. We even went to a nightclub — to Twilo or the Tunnel one night. I remember it only because in the middle of the night they turned on the lights. I guess they got raided by the police.

Wayans: I sat with Darren and he explained the vision. Because I was like, why is a black guy talking like he’s in the 1970s? This is stereotypical! But I got what he was saying — it’s a new cool.

Leto: I think rehearsal was eight weeks, which is very rare, that a director can wrangle actors for that amount of time. There were lots of read throughs and rehearsals but I think the big, most impactful part was the kind of, just the dive into character.

Aronofsky: Jared definitely has a very method technique, and he really wanted to dive into the world of addicts and stuff.

Leto: I did whatever I thought I could do in order to bring more authenticity to the role, more honesty. More truth. It’s a film that demanded that. So I spent time with a group of people in the East Village, many of whom are no longer alive — they lost their battles to addiction. They were very supportive and helpful and generous with their time and their experiences and there were nights that I spent basically homeless.

Connelly: I took to making a bunch of my own clothing and accessories. I can’t remember if I wore ones that I made in the film or if the wardrobe department humored me and used ideas I had. But I got into trying to inhabit some aspects of that character’s world — painting things that I thought that she would, drawing and sewing and listening to music that I thought she might’ve been listening to. And I spent time meeting people my age who were on the streets and using, talking to them about their experiences.

Wayans: We sat with addicts. We went to a clinic and talked about the effects of heroin. We did a lot of research. Darren took my shirt off and made me walk around the streets of New York in February because he wanted me to understand what it was like — what winter in New York was going to feel like even though he was filming in the summer. I was like, Hey bro, I grew up in New York. I know how cold it is. I don’t have to do this.

Leto: No one forced me to lose weight for any film I’ve ever done. It was my idea, and I thought that given the circumstances, given my own personal experiences around addiction and addicts, it was appropriate, physically, that he’d be in that place. I also thought that if I lost a lot of weight and was restricting my food intake, that would put me in a place of constant craving. I thought that was a good place to be.

Connelly: It manifests differently, that hunger. The lack of safety manifests differently for all of the characters and is expressed in different ways through different vices and specific addictions. I just tried to focus mostly on that sense of something missing. A lot of people can relate to that feeling.

Wayans: I’m not the kind of guy that stays in character. When they say “cut,” I’m back to Marlon, back to having fun. Jared is the opposite of me. Jared is super-method. He stays in it the entire time. So when they say “cut,” he’s eating like, raisins and a nut, and I’m eating lunch. I’m not starving myself, because I noticed black guys were still buff even though they were heroin addicts. Not everybody gets skinny, not everybody gets emaciated. So I would tease Jared often because he was crabby because he wasn’t eating.

Aronofsky: I was just Jewish mothering [Leto], and trying to constantly feed him, just because I wanted him to have the energy to get through it. But he was healthy and young, and it must help create a space for him to feel free to do what he has to do.

Matthew Libatique, director of photography: Marlon would literally be in the heaviest scene, and then cut and tell a joke. Whereas Jared and Jennifer really, it was harder for them. They had to interact with each other and deal with themselves.

Connelly: Our working relationship was good. It was at times slightly volatile — which I think was part of our characters and what they were going through at the time. It was sort of conveniently volatile during the volatile scenes, which was probably more of a reflection of our youth.

Watson: They approached acting from a different place. Jennifer was a classically trained film actress, and she really hit her stride around take five, six and seven. Jared, he had had a lot more background in television, he hit his stride around take one, two, and three. And so trying to find that magical take four was all the thing we were doing.

Libatique: There’s a scene we shot, where Harry and Marion fight in Marion’s apartment, with a handheld camera. We shot it twice. Emotionally, Jared was really there between takes one and five, and Jennifer was better later. [Darren] comes to me one day. He’s like, “I want to shoot that again. I’m going to shoot that scene again.” I’m like, “Are you kidding me? We don’t have the time to shoot that again.” And then I realized, he’s right. Because the actors needed a certain amount of time to be prepared for where they had to go.

Connelly: My son, Kai, was a baby at that time, and so I had him with me on set. He was with me every day. I was still nursing him. It was a very strange, split world, because the reality of my life was so different from the reality of Marion’s life at that time. I have an amazing photograph somewhere, where I’m getting ready to go out and I have this intense, elaborate makeup on. And I’m looking in the mirror and doing my makeup and you can see the camera in the photograph. And you can see I’m holding Kai as a baby at the bottom of the frame, getting ready to do this scene that’s a really difficult time in this character’s life.

It was the beginning of having to learn to surrender to the moment and not hold on to something. I had to learn to do all of my work ahead of time, and then surrender to the scene in the moments that I was there and we were filming, because I wasn’t really able to walk around inhabiting someone else’s world.

Ellen Burstyn’s Power

Burstyn was, by this point in her career, a five-time Academy Award nominee who’d gone on to win for 1974’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore — a legend who’d collaborated with the likes of Peter Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese, and William Friedkin, and who was now working with a young director on the cusp of 30. In Requiem she plays Sara Goldfarb, an isolated widow whose cheery front masks depression, and who starts having amphetamine-induced hallucinations in her apartment. Burstyn performed solo or played against the television and a growling fridge as often as she did another cast member.

Aronofsky: I was terribly intimidated by Ellen. The first day bringing her out to Coney Island and the boardwalk and Brighton Beach — I remember I had a camera with me and I was scared to take pictures of her, even though I was about to shoot a movie on her.

Burstyn: Darren’s mother and father were on the set every day. They’re both professors, brilliant people. When Darren shot Pi, his mother was the caterer. Seeing them and talking to them, I always wonder what the world would be like if everybody got to grow up with parents like that. She did have that Brooklyn accent, which was very helpful to me. I came in and talked to her every day so I could take up her intonation. She was my coach.

Watson: [Burstyn] was incredibly generous with teaching us. Probably the most generous with Darren, and trusting of him. And I think that was a two-way street for them. He was bringing a lot of energy and enthusiasm and ideas that she hadn’t encountered as an actress. [Burstyn] would get [to set] before Darren and I, because of what she had to go through with the prosthetics every morning. Here’s somebody with Oscars who’s considered one of the greatest actresses in our history, and she’s working harder than us.

Burstyn: The first thing was adding a neck piece that was glued on me and that turned out to be a nightmare because during the day, my body swallowed the glue. It was very hard to get off. I wore two fat suits — 40 pounds, maybe, the first one, and 20 pounds, the second one. Then we came to a ten-day break for me where Darren was shooting other things, so I was able to lose 10 more pounds. I went on this cabbage-soup diet, which is very effective for losing weight, but you eat nothing but cabbage soup three times a day. It’s not fun at all. I don’t recommend that to anybody.

Aronofsky: For me, probably the reason I made the movie, was for that scene [where Harry goes to visit Sara]. It broke my heart every time I read it. I knew that that was the center of the film — if it was a seesaw, this was the fulcrum. And it’s two people sitting at a table — how are you going to make that interesting?

Libatique: That scene was difficult to shoot because — whose scene is it? Ultimately, it’s Sara’s, because Sara is actually, whether she intends to or not, showing Harry what’s become of her in her loneliness. Harry’s coming to the realization of what’s happened to her, ironically after enjoying some success selling drugs. There’s a moment where we had her looking left to right, where you start to realize she’s grinding her teeth, and the camera wraps around Harry and ends up on his other shoulder. And now, we’re on the other side of things.

Leto: It was my first day and my first scene, I believe, with any dialogue. I was maybe overprepared at that point, just raring and ready to go. We filmed Ellen’s side first and I was so nervous and excited that I lost my voice. We had to shoot my side on another day. But I remember Ellen being so believable — her creative force swept me up into this really interesting place where I felt I was there with my mother and we were really having this conversation.

Burstyn: It was very early in his career and I don’t think he yet had the confidence that he developed after that. He was a tender young actor, which made him easy to love.

Aronofsky: I can’t say I remember how Ellen got there, but something triggered for her in that sequence that was just remarkable. We all sat there in awe watching her do a take, and we were all teary-eyed at the end. And Matty, it turns out, had fogged up the viewfinder because he was crying, and when it came back, the shot was just the tiniest bit soft.

Jay Rabinowitz, editing: There were other takes where she was brilliant but this, there was something so special. We really never could imagine going with another take. This is something that you come across in editing — you have to make these decisions between technical perfection and magic.

Aronofsky: I was devastated. Then I was watching Seven Samurai, because sometimes I’ll watch my favorite films while working on a movie. There’s this amazing breakdown by Toshiro Mifune in the movie, and it’s actually soft. I was like, “Okay. Good enough for Kurosawa, it’s definitely good enough for me.”

Burstyn: I’m thinking about the wonderful poem of Mary Oliver’s when she talks about how she wants to greet death. The last line of it is, “I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.” And I think that’s what Sara was feeling like — she wasn’t looking forward to something new and wonderful happening. She realizes that she’s getting old. And how many chances does she have to do something? Make her mark.

Not Your Typical ‘Heroin Movie’

The distinctive visual and rhythmic style of Requiem for a Dream was created with the help of a slew of collaborators who brought different ways to realize the film’s intense subjectivity onscreen. Among these ideas was the creation of the “hip-hop montage” — a fast-cut micro-montage of close-ups that was often used to summarize drug use, and that Aronofsky first used in Pi.

Aronofsky: With Pi, the whole film is in Max’s head. One of the things I loved about Requiem is that I have to deal with four points of views as opposed to one. When I read the opening scene where Sara locks herself in the closet while Harry’s stealing the TV, I got the idea, “Oh, let’s try a split screen,” where on one side you see Harry’s story, shot subjectively, and then on the other side you see Sara’s story. That started a visual grammar and different techniques that we decided to move throughout the film. Me and Matty talk about it as expressionist filmmaking — we’re not going for purely photorealism.

Connelly: I was so impressed by Matty and the way he worked. It was a totally different style of filmmaking than I had experienced. For example, there’s a scene where I have a camera rig on that I was wearing. I had never done anything like that before.

Libatique: It was basically just a weight belt and a monopod stuck out. It’s one of those techniques you have to use sparingly, or else it becomes a little distracting. It’s not unlike Spike Lee’s dolly shot. The effect was great and it spoke to another layer of subjectivity to get to.

James Chinlund, production design: I gave Darren a pitch based on the idea that we would remove the color red from the entire film, with the exception of the moment when Sara’s red dress appears. That was the crux of the design angle on that movie and he was really excited about it. But I had not pitched on a movie before, so I had no visuals or anything. He was like, “I love that idea, but why don’t you go back and bring me a pitch that I can actually look at.”

Watson: The scene with Ellen cleaning the apartment, it’s a motion-controlled camera. She basically had to do it in one take — we had to choreograph everything she did.

Burstyn: And there was no rest. It was just, do it and do it at top speed. That was very challenging. There were a lot of different technical things going on that I had never experienced before. I was panting by the time we finished.

Clint Mansell, music: Darren had wanted a hip-hop score to reflect the music he’d listened to growing up in Brooklyn. I remember him sending me a clip of the scene where Ellen Burstyn first takes the speed pills. He put “She Watch Channel Zero?!” by Public Enemy under it. It was fantastic, just brilliant, but it didn’t do anything but say, “Oh, that’s cool.” There was no subtext to it. We realized at that point we were in trouble. I had written a lot of stuff in advance, but in this hip-hopish vein. When I started seeing the rough edit, we put the music to it, and nothing really latched on. I nearly quit at one point because I didn’t think I could do it.

Libatique: [Darren] came up with this idea of what would be called hip-hop montages, because of the beats that we cut them to. We came right on the heels of the height of MTV. As much as the quick cutting has been disparaged as time has gone on, in those small bits, it worked to convey imagery quickly. When you watch the film, Harry and Tyrone are sitting in Tyrone’s apartment and nobody’s smoking or shooting up necessarily. It happens in a montage, then, you see the aftermath.

Aronofsky: We even used it sometimes when [Sara] would check the mailbox. In the same way that we all check our mailboxes on our iPhones now for a little hit of dopamine.

Rabinowitz: So much of what everybody loves about the editing of Requiem for a Dream was baked into the script. The first time there was one of those micro and macro image montages, he explains what each shot is. “SNAP, she opens the cap. BOOM, she pops one into the palm of her hand.” And he had these sound effects in all caps. And the second time he did it, he explained a lot less in the script. And the third time, it just said, “SNAP, POP, BOOM, BANG,” and you knew she took another pill.

Watson: The trap of a heroin movie is, you see people shooting up, right? That was one of the things we really talked about — how do we deal with that, because that’s not interesting just to show people shooting up anymore.

Chinlund: It was important that we show these people as people with lives and creative output. Marion and her loft and all her dreams of a career in fashion, and Tyrone was a DJ and we had installed DJ equipment in his loft. It was a story about people and how easy it is for them to get derailed. It was the responsibility of the sets to show the optimism, the potential of these characters against the darkness of the path it followed.

Aronofsky: I was never interested in heroin, per se, even though that’s what’s in the book. I tried to not mention what drug they were taking, because I felt Selby’’s larger message wasn’t about a particular drug — this really was about addiction, and that addiction could be any shape and form. There’s only that one shot of the needle going in the arm when it’s all sore and gross. I knew it had to be intense, and I knew by breaking the hip-hop montage for the first time on the actual insertion, and showing that to the audience, I was making a big statement. No one in their right mind would do that, except for a junkie who knows that’s the only way he can get a fix.

Libatique: He said to me, “You think it’s too much?” I’m like, “You’re going to ask me that? You’re going to ask me that now?”

“So What Are We Going To Do Now?”

The film sends all four of its main characters spiraling into despair as it builds toward its climax, but the most scarring sequence in the finale has to be the one in which Marion, desperate for a fix, shows up at what turns out to be a sex show for a crowd of hollering, bill-throwing men in suits.

Watson: We basically shot [the sex show scene] in the very last night. We had a closed set. We had a lot of rules and regulations going into that. It was very stressful for me, because if something went wrong that would’ve been really bad. The guys in the scene weren’t actors, except for Stanley B. Herman. The women in the scene, they were strippers by profession. They were very professional about it.

Heather Litteer, Big Tim Party Girl: I was in the underground alternative cabaret scene already, doing burlesque, go-go dancing, indie films, all kinds of theater, Jackie 60. Casting director Lori Eastside called me in and was telling me about this hot new director and who the cast was. Then she was explaining that the content was really illicit, so to make sure that we could do that. An old friend of mine was in Last Exit to Brooklyn, so I knew, Oh shit, it’s going to be dark. But when you’re in your 20s, you don’t really think about 20 years later.

Rabinowitz: I think Jennifer was only there relatively briefly, and they got those shots of her.

Libatique: One of our producers, Scott Franklin, found all these guys from Long Island, all these Wall Street guys, authentic dudes. But everybody was on their best behavior. Jennifer gets in position and we’re shooting her close-up. Nobody’s making a sound. We’re shooting, and Jennifer said in position, “Is anybody going to make any noise?” Everybody just looked at each other like, “Oh my God, yeah, of course. Yeah, of course.” We were so tense because, look what this woman’s having to do.

Connelly: It was a scene that was important to the film. But I don’t remember personally feeling comfortable doing it.

Chinlund: We had been dressing the set all day. When the shooting crew came and I left, and they were up on the 16th floor and I’m walking down Madison Avenue to go to the train, I can hear [the men] chanting from the room. It was echoing through the canyons of the Upper East Side.

Litteer: There was the one line I ended up getting, but [Darren] didn’t tell us who was going to get that until day of: “So what are we going to do now?” He showed us around the set and took me aside because he wanted me to be there in the scene with Jennifer. I was so excited. Everybody was professional. We had a little talk and it was the personal information, and he had told me a name. I don’t remember what it was, but I was like, “Great. I’m going to get a name on the credits.” But I never did. I’m still just a Big Tim Party Girl.

Rabinowitz: It was upsetting to me, how far he pushed the actors. That led us into an elaborate conversation because he was like, “Why is everybody so sensitive about sex but you can show people getting killed?” And I remember one of my arguments was, “Yeah, but the killing is fake and so is the sex.” The ramp up at the end was mathematical, but that was not so much the case with that wild sex party. We had to sift and sift — it wasn’t as beautifully designed as everything else he was doing. I’m proud of what we did, it came out pretty good.

Aronofsky: You try to create a situation where everyone’s safe and the illusion that’s on the screen covers all the tricks that you’re doing. Because of course, what’s portrayed in the film isn’t really what’s happening on set, but you’re mentally putting yourself there.

Rabinowitz: We were just about done with the cutting, and he invited Jennifer to come to the cutting room and watch it. And we had this tiny, tiny closet of a cutting room for me and Darren, and we were like, “Okay, so you’ll watch it with her.” “No, no, you watch it with her.” We wound up letting her watch it by herself, and we waited a few minutes, and we went back and her head was just down on the table — she was as wiped out as anyone else who watches the film, maybe a little more so even.

The Finishing Touches

As shooting came to an end, editor Jay Rabinowitz and composer Clint Mansell, who’d been brought on early in the filmmaking process, worked on assembling the film — and finding the famous strings score that would go on to have a life outside of the feature, especially the signature track, “Lux Aeterna.”

Aronofsky: We got Selby to New York a few times [during shoots], towards the end of the film. He hung out. He had his own chair. Every once in a while, before we were about to do a big emotional scene, I’d ask him to get the book out and to read the passage to the actors. For the cameo he was just there, and I was like, “Let’s stick Hubert Selby Jr. in the scene,” and he was all game. If you look at that scene, the shirt he’s wearing — the prison guard shirt — is way too big for him, because it was a last-minute decision to throw him in.

Leto: One day I was in the jail cell withdrawing from heroin, and screaming out in pain and it wasn’t really working. Something was off. Then all of a sudden I hear this voice reading an excerpt from the book of the scene that’s actually happening. It was Hubert Selby Jr., who had just showed up on set.

Aronofsky: There was always this idea that the film would start off wider and looser, and get tighter and tighter. At the beginning of the film, there are a lot of wide, landscape shots, and by the end we wanted it to be the size of a postage stamp. That last sequence, when all the stories intertwine and explode into misery, we really wanted to be somewhat mathematical, where even the shots were getting tighter in focal length — so less and less frames were happening with each shot.

Rabinowitz: We took a still frame from every image, from a certain point to the end, and we pasted them around the editing room. The first time you would get maybe 12 frames of each image. The second time you would get maybe one less. Each one was a few frames shorter.

The ending just had no relief. The ramp-up was taking it as far as we possibly could to land on the three of them curled up in the fetal position. That’s probably somewhat what I looked like by the end of that job.

Mansell: I’d sent Darren this CD of ideas with about 20 pieces of music on it. Little clips of things that I did. We got to the scene where Jennifer Connelly’s character sleeps with her psychiatrist. She’s leaving his apartment afterwards, and the camera’s attached to her, and she’s walking down the hallway. We put this piece of music under it — the piece that became “Lux Aeterna” — and we just looked at each other and went, Fucking hell.

I’ve never seen anything like it before. Suddenly this piece of music just attached to the screen and what was going on. Darren described Requiem for a Dream as a monster movie, and that was the monster’s theme.

Rabinowitz: Clint Mansell and Brian Emrich, the composer and the sound designer, were on from preproduction. So even as I was putting the film together for the first time, I was using the stuff that they had done. On a lot of films, more mainstream studio pictures or whatever, the composer and the sound designer wouldn’t be on until the picture edit was pretty much locked. So this was an extraordinary thing.

Mansell: When it started coming together, Darren said, “That sounds like it’d be a quartet or something.” I’m like, “Well, yeah. We could break it down that way.” And Darren said, “Well, in that case, let’s get the best quartet in the world to play it. That’s the Kronos Quartet.” He pitched them on the idea and once they saw the music, they were totally onboard. They did their own orchestrations from my demos. We went to Skywalker in San Francisco to record.

The music is, in the best possible way, heavy-handed. I can imagine more experienced filmmakers sort of going, “Oh, I think it’s a bit much,” but from our point of view, it was where we were at the time. And I think that’s the beauty of it. We didn’t have any experience at what we were doing, so we were just guided by what we liked and what worked for us.

Burstyn: A lot of the directors I’ve worked with, I’ve worked in their second film. It wasn’t until later in my career that I noticed the pattern of that: I think I liked them so much because they hadn’t been wounded yet. They hadn’t gone through the Hollywood meat grinder. They were still doing what their artistic souls prompted them to do. That initial burst of creativity when they’re young and new has a special quality of freshness that the business tempers a little.

Watson: We made that movie for $5 million. In New York at the time, it should have cost 7 or 8. One thing we have learned was that your financial restrictions can force you to come up with creative solutions. A personal theory of Darren and mine is that some filmmakers, as they’ve evolved over time, have not improved because there’s been no more financial limitation for them.

Chinlund: We were just giddy the whole time. That youthful exuberance and excitement and energy, I really do feel like that comes through in the movie, against such dark material.

The Eternal Life of an NC-17 Movie

Requiem for a Dream caused a stir on the festival circuit — it premiered at Cannes, and then played the Toronto International Film Festival, where someone reportedly had to be taken away in an ambulance. But when it came time for the film to go to theaters, it was given an NC-17 rating by the MPAA. Rather than cut the film, Artisan Entertainment agreed to release it unrated, though that would significantly limit the places in which it could play.

Watson: The first time I can remember showing it to people was at the midnight screening at Cannes. There’s all this lead-up and hullabaloo, and after the movie screens, they shine a spotlight on the filmmakers. So all the actors, and all the people that came involved in the movie, we all sat together and watched this movie in this massive 3,000-person screening room. You could feel this electric feeling as we were watching it.

Aronofsky: I remember during the screening, one of my producers was sitting behind me, and as the film was descending into the hell that it becomes, he started laughing. And he leaned forward and he’s like, “Look what you’re doing to this room.” And I remember looking around and just seeing the faces, and I just put my hands up like blinders on either side of my eyes, and sunk down in my chair.

Leto: I haven’t seen very many of my films, but Darren was adamant. He said, “Look, if there’s any time you would ever see your film, it would be tonight, at Cannes. Walk the red carpet, see the movie, and have the experience.” I really am glad that I did. I sat next to Hubert Selby Jr., and I just remember when the lights came up, there were just tears streaming down his face. There was a standing ovation, and he just couldn’t believe it.

Aronofsky: Then of course, we never got an R rating. The studio was like, “If you get an R rating, it’s going to mean you’re going to make this amount of money and you’re going to get this type of release. And if you don’t, we don’t know what to tell you.” But I felt like, look, if you retreat from the intensity of this by cutting back things that they’re uncomfortable with, you’re undermining the purpose of the film and this critique of addiction. That’s sacrilegious to me, after this huge effort, to suddenly try to make it less disturbing.

Watson: We had an appeal screening when they gave us an NC-17 rating, and we tried to peer into a very murky world — the closed-door group of people that makes that decision. They did say, “Hey, we know this movie would be more effective than what you’re setting out to do for a rated R, but we just can’t do it, sorry.” That limited how many screens it could go on. But on the positive side, controversy creates publicity. And so we definitely milked the publicity of having the NC-17 rating as much as we could.

As I’ve gotten older, I meet more and more young people, and when they find out that I made that movie, they flip out. They’re always surprised that I didn’t put that up front and center. I’m humble about it, but at the same time, I’m definitely proud to have made a movie that feels iconic. And I don’t think we intended to make a movie that would be on the shelf, so to say, but we did.

Rabinowitz: I’ve been going at this for about 30 years now and Requiem is by far the most quoted film that I’ve worked on. It really did become a reference point for so many people in films, in commercials, in television, across the board. I’ve had the good fortune to work on a lot of wonderful movies, but there’s no question that Requiem has a special place in that. It was a very trying experience. It was brutal at times. There were probably moments where I wasn’t sure I was going to make it — and yet I know how incredible it was. [Darren] was just focused like a laser beam, knew exactly what he wanted, and he just kept pushing until we got it.

Mansell: I don’t have any children, but I imagine [making scores for films] as sort of like having children. You do what you do and then they go off and have their own lives. I support this football team called Wolverhampton Wanderers. We played this big game in 2003 — a playoffs final — and when the teams came out onto the pitch, they played “Lux Aeterna” over the PA. Oh my God, I couldn’t believe it. I knew we were going to win that game — we did, we won three-nil.

McDonald: Everyone asks me, What’s the third thing? No red meat, no refined sugar — what’s the third thing? Just between us? No orgasms. That’s the one that puts people over the edge.

Litteer: It’s a great film. As someone who’s known a lot of people who’ve had problems with addiction, it’s a very sad thing to watch someone go down like that. But [playing my part] did affect me being able to break out of that, to being more of a serious actress. I think that I thought it was going to be the thing that would catapult me into more success. But it was hard for me to get people to see me in other ways. Once I was doing a concert at Joe’s Pub and I finished and somebody screamed “Ass to ass.” I’m not bitter at all — I’m happy to have been part of such a cool film and I’m ready to do more things. But in the end, I feel like I’m the Requiem for a Dream girl.

Chinlund: I think people recognize it as being sincere and real and entirely devoid of irony. We meant everything we said, we met everything we did.

Connelly: It was so innovative. Darren was so brimming with ideas — the story, the themes, the way it was shot, Matty’s work, the editing, the sound design, the music. In my life at that time, I was so beside myself to be part of that moment and be able to explore, creatively, myself, because it was beginning a new chapter for me in my work. Having started as a kid and having had a very different relationship to acting and making movies for many years, it was a foray into a different kind of way of working.

Burstyn: I feel if I graded my work, it would be up there close to the top, if not at the top.

Libatique: I grew up as a first-generation Filipino in America. And from my personal experience, when I’ve met people in the world, the same way Spike Lee touched me, Requiem for a Dream has touched other first generations or minorities to feel like they can become filmmakers.

Wayans: Everybody has a deficiency. Everybody has a deep-seated pain that allows them to seek drugs and artificial elation. At the end of the day, I think [the movie is] about really coping and dealing with what’s hurting you. Finding a sober way to deal with that and fill yourself with love. Because it’s all a deficiency of love that drives us to do the things that we do that ultimately destroy us.

It was a lesson for me, especially right now in my life after losing my mom. I understand that there’s never going to be anything to replace her. The only thing I can seek is a different kind of love, a healthy kind of love.

Leto: I remember people would have that DVD — when people got DVDs — people would buy that one because they wanted it in their collection. People wanted to have Requiem front and center on the shelf. I don’t know who would watch it more than one time, but it was just one of those films. Maybe still is … what the fuck do I know?

Making films is a tricky business. They don’t often turn out how you hope they would. This one met and exceeded all expectations. It feels good to be part of a great film, that’s for sure.

Aronofsky: It’s a whole different world now. If I were a young storyteller, I’m not sure I’d be making an independent film. I’d probably be trying to tell a story in another type of way. So much of film releases have become these really big movies, and mostly you’re looking for an audience in other ways.

I haven’t seen [Requiem] in a very long time. There was an HD release years ago, and Matty had done some work on it, and everyone was like, “Look, can you just watch it at the end, just to make sure everything’s right?” I could remember shooting every single thing. I was completely aware that I couldn’t make that film — or wouldn’t want to make that film right now — because it’s a different human being who made it. But I tried to hold onto that energy, because I think that’s why you do it. You’re trying to make something different.

In honor of the 20th anniversary of Requiem for a Dream, the movie has been given a 4K Ultra HD release as a Blu-ray and digital combo pack.