Spoilers follow for the first season of Andor.

In a year of relentless IP churn, Andor feels like a miracle. As networks and streamers put forth projects that mimic, nearly beat for beat, other recognizable properties, Andor’s greatest strength is how different it feels from the rest of the Star Wars universe. There are no Jedi here, no Skywalkers, no discussion of the Force. Emperor Palpatine is mentioned but not seen. This prequel series, set five years before the events of 2016’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, echoes its predecessor in its on-the-ground depiction of war and dissent, a pro-proletariat perspective that dares to interrupt the franchise’s space-opera sameness. For Tony Gilroy, who co-wrote the film and is Andor’s creator, showrunner, executive producer, and writer, the projects align with his belief that human behavior “is more powerful than anything people design, and more powerful than any political system” — even the Galactic Empire.

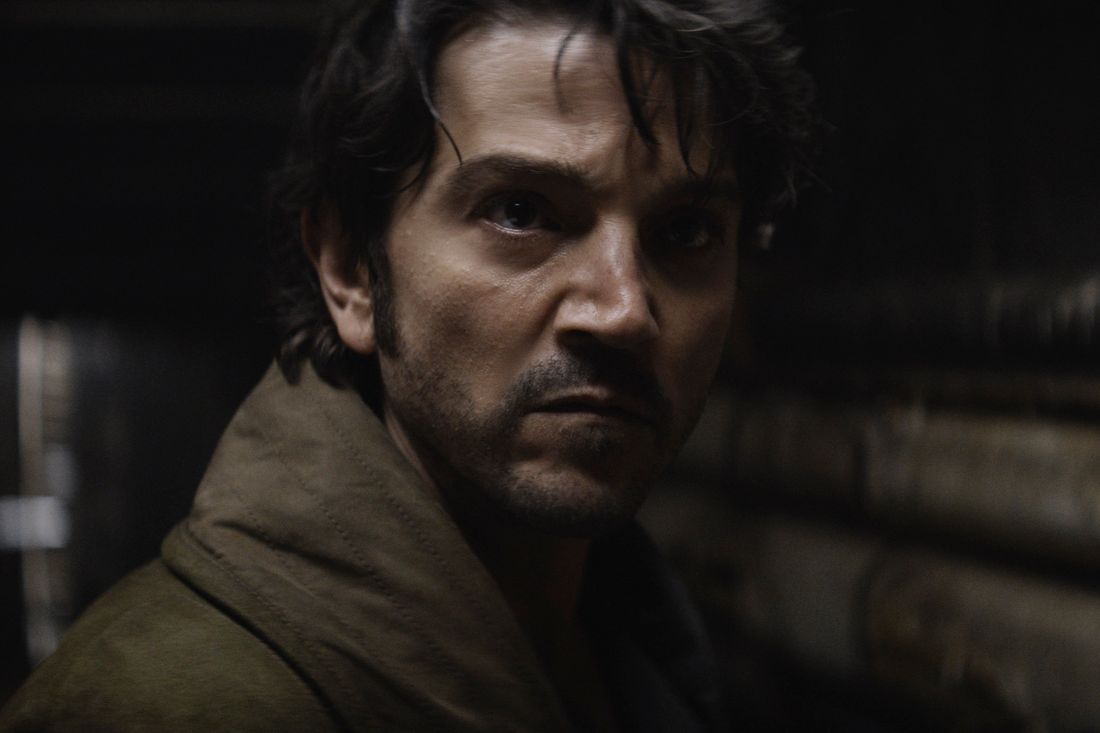

Andor follows Cassian Andor (Diego Luna), who in Rogue One sacrificed himself to slow the spread of the Empire and sabotage its world-destroying Death Star weapon. The series opens before Cassian’s transformation into cunning spy; a bit of a ne’er-do-well, he owes money to many increasingly irritated friends and acquaintances on Ferrix, where he lives with his adoptive mother, Maarva (Fiona Shaw). He has a history of anti-Imperial activity and was forced into war at a young age; he’s searching for a sister he can’t find and a purpose he can’t pin down when his killing of two Empire-aligned security guards sets off an Imperial Security Bureau manhunt.

Over a series of mini narrative arcs built into the first season’s 12 episodes, Gilroy and his team of writers and directors use murder, a heist, a prison break, and a funeral to track Cassian’s evolution, in the span of a year, from passive dissenter to rebel willing to risk his life to combat dictatorship. Andor is more grimy, compelling, and immersive than Star Wars has been in a while, and for Gilroy, it’s another opportunity to explore how human emotion, in all its forms — empathy and aggression, angst and love — is more potent than any system that attempts to control it.

Andor is a portrait of the central character’s radicalization, but also of the planet Ferrix, where he was raised. Can you talk about the choreography of the final episodes, and about Maarva’s funeral turning into an uprising? How did you determine the pacing of that transition point from an expression of mourning to one of rebellion?

It was a frame I had early. I knew where I was going to end. There were some gaps in the middle, some big things I took to the writers’ room, like the prison. But in plotting it out, the trick is if you’re going to have this many characters and you’re going to send them this far afield, there has to be a convergence at the end. The idea of the funeral was amped up by the idea that Maarva could do her own eulogy. We did this in Rogue One with the Mads Mikkelsen hologram and it was so potent. Once that was on the sketch menu, the structure of the funeral became an extension of the work we had been doing on making a culture in Ferrix. Notice in the first episode, all the gloves outside the Grapplers’ Hall — we went really, really deep in a place we understand. If Maarva is going to give her eulogy, and she had been part of the Daughters of Ferrix, what would that be? Somewhere between an IRA funeral and a second-line New Orleans funeral.

Music is a huge part of it. Nick Britell, the series’ composer, and I had just met; we hadn’t worked together. The very first thing we did was make up all the diegetic music and sounds for Ferrix: the warning sounds, all the rhythmic stuff. Then I said, “I need seven and a half minutes of music that I want played live by a civic, amateur community orchestra.” How we got to know each other was making that piece. We built the music, we had it all chaptered out, and it has its own choreography. There’s a horn section, there’s a flute section.

We thought about how great it would be, tactically, for the community to split up their resources. They’re not supposed to have more than 30 people in the square, so they sneak in all these people. It’s very dramatic, all those people converging with the different pieces of music. We’ve done a lot of these different crescendos in our lives, and it was all hands on deck to figure out how to do it. There’s a certain way to prep action scenes, and my brother John Gilroy is on full time as an editor on the show; Ben Caron and his team came in. From a production standpoint, it’s a long conversation about how you time everything out, make video cuts so the timing of the music works out. We have an eight-acre set that’s almost 360 degrees, so we can run people through it and not worry about the camera. Thematically, the idea was to have this place we’ve grown to understand and love mirror Cassian’s awareness and consciousness.

Ferrix is one of a few new planets on this show, as well as Kenari and Aldhani. How did you write new cultures, new rituals, new belief systems for these places?

They all have to be different, right? Everything I do starts really, really small. I mentioned those gloves — that’s a tactile entry point for me. My primary collaborator on the whole show creatively — almost a co-writer in the most important way — is Luke Hull, the production designer. Luke and I started working a year before anybody else got involved, because everything we do, we have to design, and that’s the overwhelming part. I worked with Luke before we had a writers’ room, and then he was in the room with us while we were doing everything else. I drew on a cocktail napkin a map of what I thought Ferrix looked like with the salvage yards, and where Maarva would be, and Rix Road.

We built the ritual of the Time Grappler. They don’t wear watches on Ferrix, so I told Nick, “We need these tones for eight or nine times a day.” And you ask questions: Where do they eat? How do they live? What’s the community like? What’s the caste system? Screenwriters, dramatists — if you’re working well, you’re making worlds all the time. So it’s just making a world where you have to do everything. [Laughs.] There’s a ferry, and there’s a park and ride. What do they charge you? Wouldn’t somebody be outraged by that? We went really, really deep. And we’re going to do it again — we’re doing it again right now.

You said the final line of this season is important to understand where the story is going, and that line is Cassian’s “Kill me or take me in” to Luthen. What should we glean from that?

It’s a blood oath. I’m in. This question is resolved if we go forward. Those Stations of the Cross Cassian marched through during the first 12 episodes, there’s no turning back from that. The issue we will not examine in season two is his commitment to the Rebellion. It will be about many other things.

You’re a great writer of negotiation scenes. How do you approach a conversation where there’s a push and a pull?

It’s hard to write scenes about people getting along. I don’t do that very much. In a glib, quote-y kind of way, all relationships are negotiations. I’m drawn to people at cross-purposes. There’s not much difference writing Luthen and Cassian in the factory and Eedy and Syril at the breakfast table. You have to be inside everybody’s skin on both sides of the net.

What’s the easiest part of planning an action scene, like the shootouts and the space fights? And what’s the hardest part of planning a conversation scene, something more intimate and small-scale?

There is one truth for both: It has to be real. It has to be on a floor of reality; you have to believe in it. If it’s an action sequence, it has to be a physical environment you understand, that you’ve really built. In your mind, it’s exhausting sometimes — you have writer’s block, and you’re just sitting there and days go by. That’s because you have to take all the effort to make this place in your head that really lives, so that you can create a reality for the things that are going to happen there. It has to be the same thing in a conversation scene.

The other day, I had to make a presentation package for somebody, and I had to rush some scenes that were not finished. I got into one and I realized the foundation of it was built on a swamp. I can’t do it this way. I have to reorient the reality of what happens. I have to reset the ground rules. If you know all the characters and you know what they want, it begins to take care of itself. What I’ve found over time is there’s no shortcut other than making it real: Why are you here? Why are you in the car? Why are you on the phone? Why are you doing this? What happened before this? What do you want? What led us here? If you own all that, you can go forward.

So your approach to breaking down stories is asking a lot of questions about them and disrupting the narrative we’ve come to expect. Did you see story elements, like Kino not being able to swim, and Maarva dying offscreen, as being disruptive? They deny viewers catharsis and subvert our expectations of where the story might go.

In the case of Maarva, I know she’s coming back to give the eulogy. When you saw episode 11 and she was dead, did you say, “Oh, I know she’s coming back in a flashback,” or were you surprised when her hologram popped up?

Absolutely surprised.

Okay, well, that’s what I want. I want you to turn the page. For Kino, what’s better than that line? And what’s better than realizing that he’s known that all day long? If you already had a brand-new halo, what better way to light it up? But Maarva, I know I’ve got an ace in the hole there. I wouldn’t do that if I didn’t know I had a card to play.

In the finale post-credits scene, it’s revealed that the Death Star is under construction using the pieces Cassian and the prisoners built in the Narkina 5 prison. When did you decide to include that glimpse?

That’s something I brought to the writers’ room: “Is there any prison that would be worth it? Can we do anything new and fresh? If we can’t, we’ll do something else, but let’s try.” Then someone said, “What if the floors are electric?” And we spent the better part of several days building the prison. And what are they building? Well, they’re building a part for the Death Star. Of course they are! What’s interesting about the first half is Cassian’s proximity to so many large events, and that may presage something in the second half, which might be more of a take on the wind of destiny. What better thing to have him building than the thing that will ultimately be the place he ends?

The moment we had that idea, we had to keep it secret. Don’t tell anybody. We have this remarkable visual-effects department with Mohen Leo and TJ Falls. They were with us on Rogue One. It’s hard to express how important they are. We make small asks and treasures come back. They were like, “Can we play with that idea?” They went away and tinkered with that; they had a lot of fun.

Were the shots of Syril eating spherical cereal a Death Star clue?

You know what? I never knew. As closely as I monitor everything — every sideburn — I was very pleased to see the cereal. It’s a happy accident. Maybe Toby Haynes thought of it. If it was, it was a communal decision outside the realm of my purview.

Andor features a few actors returning from Rogue One, including Diego Luna and Genevieve O’Reilly. Did you write for what you perceived as their strengths or to challenge them in different directions?

From Rogue One, I had good exposure to Diego all the way through, so I didn’t have to be convinced about anything. I knew he could do everything. Genevieve was a drive-by for me in Rogue One. I talked to her and really liked her, and I’d seen other things she did, but I didn’t know how good she is. I had audition with some other people pre-COVID, when I was in London and I was still going to be directing Andor. I was much more tactile with the show at that point, and I very rapidly figured out that she was a raw diamond. She could do all these things people hadn’t asked her to do. You start to realize what actors can do and you lean into it. How far could she go? We kept making it deeper as we went and as we realized how cool she is.

Mon, Cassian, and Luthen (Stellan Skarsgård) are all performing a version of themselves — there’s a private self and a public self because they’re living in this time of excessive watchfulness. As a writer, how do you find the line between a character’s sincere self and their mask?

For Genevieve, it’s survival. She has to protect herself. In a way, her revolution is the hardest one of all, because she has to do it under glass. Everybody is watching all the time, and she has nobody she can count on. Her ability to switch back and forth between public and private is entirely personal and with the camera. I love actors that can do private that way.

With Stellan, it was kind of clammy. The gallery is a great idea for a spy recruiter; it gives us access to all kinds of things. What a great cover story. But: Oh my God, secret identity. Is he going to be this guy here and this guy there? How is that not going to be cheesy? Over time, we’re like, Okay, let’s make it two: there’s natural Luthen, and there’s Luthen of Coruscant. When he’s making the transition, when he’s going back to Coruscant and you’ve only known him as natural Luthen, he’s alone on the Fondor Haulcraft, and he puts on his face, he puts on his hair, he puts on his jewelry. He does this whole transition, this butterfly moment. What Stellan had said to me earlier in rehearsal was, “Well, natural Luthen is this,” and he has his hands down, “and Luthen of Coruscant is this,” and he opens his hands to the side. And you go, “My God, that’s just it.” Some actors say, “The shoes make me feel the part,” or some actors say, “I need a monocle.” For him, it was that gesture.

Luthen’s theme, I think it’s almost my favorite thing in the show. When Nick played me that cue, I said, “I want, like, a breath. [Makes an exhale noise.] It’s like giving it away.” It’s so sad.

When I reviewed Andor, I called it “Michael Clayton in space,” because I thought there were certain similarities between various lines and characters. Cassian’s “Do I look thankful to you?” made me think of Michael’s “Do I look like I’m negotiating?” Dedra and Karen are both middle-manager-style villains. Did you think about that while working on the series?

No, it wasn’t on my menu. I try to stay away from anything I feel like I’ve done before. If there’s an overall thesis, it’s that I believe human behavior is more powerful than anything, and it sort of leaks like water through a spout, through anything you put it on. It rusts out everybody’s intentions. Whether it’s hitmen and organizations or law firms or huge corporations, or a marriage — what we need, what we’re afraid of, all the things that fuck us up, is more powerful than anything people design, and more powerful than any political system. I guess I keep working on that all the time.

I was very moved by Nemik’s manifesto and the idea that “freedom is a pure idea.” Can you talk about writing that?

Nemik went through a lot of passes. We always wanted a Trotsky: the young, naïve radical. If you’re going to have Cassian ingesting all of the possible forms of conversion to the Rebellion, we needed a dialectic character. Then we cast Alex Lawther. A lot of the rewrites and upgrading along the way is based on the cast, and the cast we have is so good. Even watching him audition, it was like, We can go anywhere. The campfire speech he gives in Aldhani was the can opener. When we finally cracked that, it was like, Oh, here he is. The second speech is the mercenary speech he gives Cassian in the morning, and that went so easily. The power of the manifesto — episode 11, that scene, we had kind of late. You get on a roll with those things, and you just try to break your own heart. You’re trying to write speeches for the things you believe in. Sometimes it takes a long time to find the voice, but once you’re there, they tend to go quick.

Then we married it to those shots, and when we did the music, it was really Nick. It was a big burden. Music asks for stuff. What do you ask the audience for? Are we being greedy? Are we being proper? Are we being respectful? I’m very proud of that speech.

Certain elements felt inspired by recent history to me. The Public Order Resentencing Directive seemed like the Patriot Act, and Bix’s and Salman’s torture sequences made me think of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay. Am I being too specific?

You could point at that, but there’s 3,000 years of recorded history too. You can go to the Montagnards, you can go to the Urgun, you can go to the African National Congress, you can go back to the Roman revolution. Changing people’s sentences, fascism, oppression — you can pull everything. Some things are more germane for what we’re doing now, for the second half, but watching revolutions come together and watching political factions within them, there’s a universal truth: There’s almost never just one forward motion. There are all kinds of people moving in different directions. These are universal concepts.

After Rogue One and the main trilogy of films, we learn that the Revolution failed, the Empire persisted, Palpatine is back. While you’re writing, are you considering the ways revolutions don’t turn out as the people who were involved intended them to go?

No. I don’t think past my frame at all. What we’re working on now, the second part of this project, is not about Cassian becoming radicalized. It is very much about, How difficult is it for the Rebel Alliance to come together with all the outliers and original gangsters? Different agendas and betrayals? The tension of the next four years as things pull together? The effect of time on people? But I don’t look past that because my characters don’t know what’s going to happen after that.

So it’s not useful to consider that.

It’s useful to consider, obviously, that I know he’s going to die, and he’s the guy who gave his life consciously and willingly in Rogue One. When he and Melshi are on the beach and he finds out his mother is dead, Melshi says, “Let’s split apart,” and Cassian gives him the gun. Melshi leaves and Cassian’s on the beach alone. I’m very pleased Ben was on the ball and made that feel like the end of Rogue One. But I wouldn’t do more than that. That’s more in destiny than plotting. I’m not thinking about the destruction of Alderaan.

Will we hear about Cassian’s sister again?

I’m not going to answer that.

In some other interviews you’ve given about this season, you’ve described yourself many times as an “old white guy.”

[Laughs.] Oh my God.

But I will say that for an old white guy, you’ve put together a version of Star Wars that is very racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse, with actors from an array of backgrounds. I’m wondering how important that was to you during casting — if it was important.

It’s not even important, it’s essential. It’s what we do now. That is the state of the art. That will not change, and thank God it’s here. In fantasy, and in a story that has a lot of political connotations, it presents some interesting avenues. We’ve got interesting conversations about things going forward that I’ll be happy to talk about next year. It’s like having a queer couple. It’s just a relationship.You want to be unconsidered about it. You want to make it all as natural as you possibly can.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.