Say “Andre Braugher,” and you hear Andre Braugher. The 61-year-old actor, who died yesterday after a brief and unspecified illness, was a star of Homicide: Life on the Street, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, and Men of a Certain Age, as well as every scene he ever appeared in.

He was visually striking, with his shaved head, searching eyes, and wry smile — and he had a gift for making characters seem earthbound and lived-in, even when playing such extraordinary men as Detective Frank Pembleton on NBC’s Homicide: Life on the Street; the trailblazing Captain Ray Holt on Brooklyn Nine-Nine; the experimental oncologist Ben Gideon on the medical drama Gideon’s Crossing; the supercompetent title character of the miniseries Thief; and the warriors, neurotics, and schemers of Shakespeare’s tragedies (including Richard II, Henry V, Claudius, and Iago). It was the kind of face you could study.

But when Braugher spoke, a spotlight irised him, and you knew you were in the presence of greatness. He had theater degrees from Stanford and Juilliard, but they might as well have been for music. When he acted, the words were notes; the sentences, lyrics; every monologue, an aria. Actor-comedian Joe Lo Truglio, who acted with Braugher on Brooklyn Nine-Nine, wrote on Instagram about hearing his co-star “belting bass-y vocals” from his dressing room: “The man was so full of song, and that’s why the world took notice.”

Braugher’s voice could be empathetic, incisive and bitter, all at once, even when pronouncing one word: Really? Interesting. Hah! Goodnight. Even his nonverbal sounds were inspired: the hmmms, the chuckles, the sniffs. The voice could reassure, cajole, bully, inspire. It could burn away lies. It could draw viewers in for what they thought would be a warm embrace, then slug them in the gut. It could drop a breadcrumb that helped you wind your way back from the end of the story and note the instant when everything changed.

The voice was showcased most brilliantly on NBC’s Homicide, the still somehow underappreciated series adapted by filmmaker Barry Levinson and screenwriter Paul Attansio from David Simon’s book about a year in the life of a Baltimore squad room. It was a show where people used words the way other crime-show characters used fists. Braugher’s Lieutenant Frank Pembleton was the heavyweight champ: an intellectual, philosophical, hyperverbal Catholic who wrestled with the implications and implacability of evil each time he stepped past the crime-scene tape, and who could work a suspect over like a heavy bag without raising a pinky. The character was a drug problem away from being a cliché’d cable-prestige-drama antihero — self-centered, brusque, withering, dismissive of intellectual inferiors. “What you will be privileged to witness will not be an interrogation, but an act of salesmanship, as silver-tongued and thieving as ever moved used cars, Florida swampland, or Bibles,” Pembleton declares, “What I am selling is a long prison term, to a client who has no genuine use for the product.”

You adored Pembleton because the character was so complex and Braugher so thrilling to see and hear. Like Al Pacino, Christopher Walken, Denzel Washington, and other verbally acrobatic leading men, Braugher gave his line readings syntactical detonations of misdirection, revelation, wit, and fury. They were likely to include counterintuitive hesitations and repetitions as well as bonus hyphens, em-dashes and ellipses. He didn’t just put across the text and subtext: He marked it up and added footnotes. And if the spirit moved him, he’d haul out a metaphorical paint can and tag a wall, as in the opening of the Law & Order/Homicide crossover episode, where Chris Noth’s Detective Mike Logan delivers a murder suspect (John Waters!) to Pembleton at Penn Station in Baltimore and they try to out-alpha each other by proclaiming the greatness of their hometowns. Pembleton one-ups Logan by telling him that Dorothy Parker got famous in New York and died there, then spent years after her death in an urn on a Wall Street lawyer’s desk. “And where does she end up?” Pembleton sweeps his hand over two windowed sides of the station and croak-sings, “BAAAAAAAAHHHHL-tih-moar.”

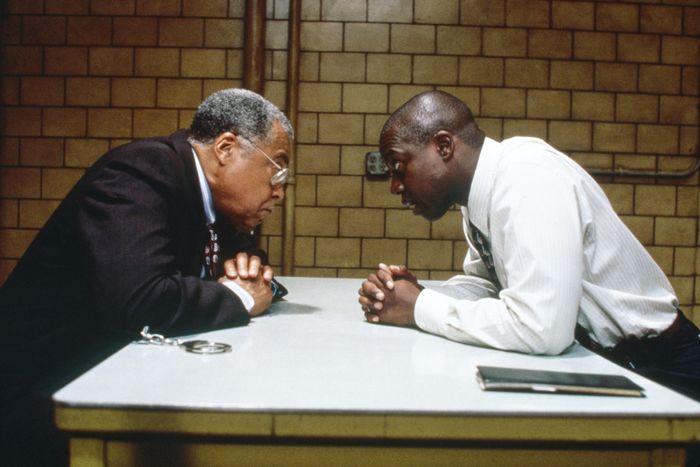

In Homicide’s celebrated interrogation-room scenes — both the audience and the characters called that room “the Box,” as in hot box or black-box theater — Braugher brought the totality of human experience into a tiny space. When he was done leaning into a defiant suspect’s face and rose to his full height, you wouldn’t have been surprised to hear thunder roll. Braugher often made you wonder if Pembleton had a trick up his sleeve or was just making the listener believe he did, even when neither thing was true. Why? Maybe to keep you off-balance, like Pembelton’s targets, or maybe because it was fun to be Jimi Hendrix with a Stratocaster. The opening episode of Homicide’s fifth season is structured as a documentary about the characters, an in-show equivalent of Simon’s book. It starts with Pembleton ranting into the camera and pronouncing the word “violence” with only two syllables (emphasis on “Vyyyyy”). In a metafictional acknowledgement of the lure of Homicide, Pembleton describes a detective in the Box starting “an uninterrupted monologue which wanders baaaaack and forrrrrth for a half-hour or so, eventually coming to rest [he leans in for a very tight close-up] … in a familiar place: You have the right to remain silent.”

Each pair of detectives on the show was surprising and pleasurable in its own way. But the teamwork of Pembleton and his partner Bayliss, played by Kyle Secor, was a level up. The two actors had such chemistry that just watching them drive in silence after a fight was hilarious, because you knew one of them was going to eventually chime in with a theory or rebuttal or counter-narrative and get the relationship going again. You waited for that moment where one or the other would say something provocative and the other would react.

Levinson was so knocked out by Braugher and Secor’s rapport while filming the pilot that he suggested building a whole episode around the team interrogating a murder suspect in The Box. The result, “Three Men and Adena”—written by future Oz creator Tom Fontana—plunges deep into Bayliss’s first case as the “primary,” the murder of an 11-year-old named Adena Watson. It follows Pembleton and Bayliss as they count down an eleven-hour deadline to secure a confession from the main suspect, a peddler (“a-rabber”), named Risley Tucker, played by the acclaimed Negro Ensemble Company member Moses Gunn, in his final performance. The extratextual power that flows between a giant of the previous generation of Black actors and a rising star of the next makes this episode feel like a passing of the torch, on top of its merits as a procedural and performer’s showcase. (Savor how Braugher unspools Pembleton’s recitation of Tucker’s sexual history in a room-temperature voice, then downshifts to an insinuating whisper as Pembleton leans in and says, “…because you’re an alco-HOL-ic.”)

Braugher’s voice was so clearly the engine driving the series that the writers eventually got the bright idea to challenge the character (and win Braugher an Emmy) by giving Pembleton a stroke that took away his ability to speak. He got his voice back faster than they’d envisioned because having Andre Braugher not talk was bumming everyone out.

He broke through as a screen actor with a supporting role in Ed Zwick’s 1989 Civil War drama Glory, playing Thomas Searles Jr. a free and educated man who joins the infantry and fights alongside former slaves. What’s most remarkable about the performance isn’t the characteristic excellence of Braugher’s brushwork (notice how Searles’ posture and gait contrast with the more easygoing body language of his platoon-mates) but the fact that he’s playing a character who is coded as pampered and weak (the drill sergeant derides him as “Bonnie Prince Charlie”). Yet he goes face-to-face with Morgan Freeman and Denzel in movie-star flamethrower mode and walks away only mildly crisped. The matter-of-fact way Braugher portrays Searles’ belief in the armor of education and breeding makes the character seem honorable but naïve rather than mockable. The performance conveys the idea that the man has no idea how strong he is but is gradually figuring it out. The breadcrumb moment occurs in a scene where Searles is humiliated during bayonet practice. It ends with Searles bursting into tears, then breathing his way through the episode until he’s functional enough to make eye contact with an officer. Life goes on, and it’s better to be embarrassed than dead.

Braugher was so assured that it was probably inevitable that he’d keep getting cast as public officials, military and police brass, and legends of one kind or another. He was the Secretary of Defense in the Angelina Jolie action thriller Salt, a judge in The Juror, the governor of California on Bojack Horseman, master thief Nick Atwater on Thief, and a submarine commander on the military-thriller series Last Resort who’s essentially an American counterpart to Marko Raimus in The Hunt for Red October. (Braugher’s dead-eyed certitude in a scene where the commander fires a nuclear missile to bluff two American bombers into turning around is so chilling, it briefly makes you wonder if a commercial TV series has the nerve to show the start of World War III.)

But Braugher often seemed to have more fun in parts where the stakes were smaller and the laughs bigger. A stealth candidate for Deepest Braugher Performance is Men of a Certain Age, a TNT comedy-drama about three middle-aged men created by Mike Royce and Ray Romano and co-starring Braugher, Romano, and Scott Bakula. Braugher’s character, Owen Thoreau Jr., is a happily married man who runs a used-car dealership owned by his glowering, micromanaging father (Richard Gant). Their scenes together border on sitcom Arthur Miller, with Owen feeling the sting of his father’s mistreatment in a public workspace and (mostly) keeping his cool. Some of Braugher’s best work on the show happens in subplots about the everyday setbacks and miseries of life, like the episode where Owen’s home renovations are shut down by the city and he can’t get another permit, no matter how creatively he butters up the worker handling his case. Braugher’s increasingly big, sad smiles during Owen’s second visit to the permit office capture what it feels like to realize that no matter what you do, you’re gonna lose.

As Ray Holt, Braugher was to Brooklyn Nine-Nine as Alec Baldwin was to 30 Rock: a supporting player of such versatility and ferocity that he never had to steal scenes because everyone else handed them over. The writers spoke of how they’d devise wild material for Braugher just to see how he’d pronounce a word (such as “birthed” or “velvet” or “vindication”). A whole documentary could be fashioned just from scenes where Holt is called upon to play drunk. Sometimes the character is drunk and seems drunk. Other times he’s drunk but trying to seem like he’s not. (In one such scene, a tipsy Holt pronounces the word “Nothing” as “Nuh-THING???” in a Bugs Bunny–in–drag falsetto.) A tour-de-force sequence finds Holt needing to strategically “play drunk” at a party. He spitballs potential character motivations like a professional actor, then acts so subtly that no one notices what he’s doing and the point is lost.

His career was such a matter-of-fact and consistent demonstration of excellence that when it suddenly ended, much too early, it was like learning that a beautiful building you used to pass each day had been demolished overnight. Frank Pembleton would have delivered a bitter, blistering monologue about that. Ray Holt would have tied one on and muttered while constructing a balloon replica, impeccably pronouncing French terms. And Braugher would have dazzled as both, making every word sing.