I’ve always been drawn to mysteries, beginning at a young age when I was still in Korea. The other day at my parents’ house, I found something I’d forgotten about: a six-volume set of Korean translations of classic mysteries by the old masters like Edgar Allan Poe, Dashiell Hammett, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Agatha Christie, which we’d brought with us from Seoul to Baltimore when I was 11. We had been poor in Korea, living in one small room that barely fit basic necessities, and I was only allowed toys that wouldn’t take up space — small pebbles for Korean jacks, a rope, chalk. Since book space was limited, I had to borrow one book at a time and got to keep only those I got as birthday presents. The mystery set I’d gotten for my 10th birthday. When we moved to America a year later, I begged my parents to let me bring it, arguing that I’d need something to keep me company until I learned English. After our move, I read the set again and again in a continuous loop, my only refuge in this foreign land where I didn’t speak the language and knew no one, where books were comprised of squiggly shapes I couldn’t decipher. I never got bored by the repetition; I elaborated on the stories, acting them out, imagining what happened between the scenes, after the ending.

Did I get this set because I loved mysteries or did I come to love mysteries because I got this set? I can’t remember, exactly — in those days in Korea, price considerations drove my parents’ purchasing decisions more than anything else. Regardless of when it originated, my love of mysteries intensified in those formative years of transitioning from Korean to English. In part, it was the familiarity bred by the repetitive reading, the soothing comfort it brings me to hold one of those old volumes even now, decades later. But even more, it was the intellectual exercise of using deductive logic to solve the puzzle, my understanding of how the author constructed the pieces deepening with each successive read. It was like playing with the Rubik’s Cube, another favorite pastime during my first days in America; at a time when so much was disorienting and senseless, I took refuge in things with an internal logic, that brought me a semblance of order.

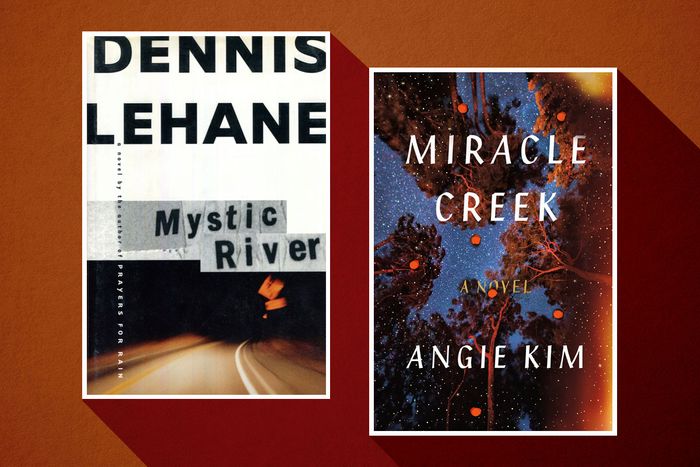

I first read Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River at another time of great transition in my life: during my initial days as a stay-at-home mom, right after the birth of my first child. I’d picked it up expecting a quick, fun murder mystery I could fit in during the baby’s naps. What I found was something more: a contemporary twist on the classic whodunit, with an inventive structure with half a dozen narrative voices weaving around each other, flashbacks and flash-forwards intertwined with the present-day murder investigation to give us not only the clues to the mystery, but a searingly intimate examination of the interior lives of the people affected by the murder. With my old favorites, following the investigation and tracking the clues to solve the crime was the point of reading; with Mystic River, I kept turning the pages late into the night to spend more time with the characters who were baring their souls to me, telling me their life stories, their most shameful moments, their experiences with everything from gentrification to the death of a child. I was hooked, and I sought out other novels that fit this more-than-a-mystery box: pretty much the entire collection of Laura Lippman, Kate Atkinson, and Tana French; Chris Bohjalian’s Midwives; David Guterson’s Snow Falling on Cedars. I loved how they used the mystery frame to immediately pull their readers into the narrative and propel them forward, but how they forced us to slow way down as we went deep into the psyche of the narrators.

When I started writing my first novel Miracle Creek a dozen years later, it wasn’t even a question that it would be a mystery. A few other things I knew off the bat: First, the mystery would be a who-/how-/why-dunit into a tragedy, a fire in a pressurized chamber for hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). (I tried HBOT in real life, and although I credit it for healing my son’s ulcerative colitis, being sealed inside a dark, small chamber filled with pure oxygen gave me nightmares about fires and explosions.) Second, the HBOT operators would be a Korean immigrant family similar to mine. And third, I’d structure the mystery element of the novel around a four-day murder trial, drawing on my experience as a litigator. While I generally despised the practice of law, I loved being in the courtroom — telling the story through the openings and closings, cross-examining witnesses, objecting and raising arguments, all of it — and I loved writing the courtroom scenes even more, at times feeling like I was back in the courtroom (except better, because I could control exactly what the witnesses said!).

Yet despite having identified those disparate elements from my life that I wanted to incorporate in the story, I still had no idea how to structure them into a coherent narrative. I’d written and published short stories, but never written a novel, much less a mystery. I read dozens of books on how to plot and structure novels, but I needed something more specific to the type of literary mystery I wanted to write — something that illustrated how to use the mystery frame to immediately pull the readers in and propel them forward, while also having a Trojan horse of sorts, a way into the lives of a large cast of characters.

What I really wanted was a Dennis Lehane master class, which he sometimes teaches, though nowhere near me and not at that moment. So I made one for myself: I sat in my tiny writing nook and reread Mystic River from cover to cover, multiple times, and dissected it down to its component scenes. I created a detailed outline, color coded by character, and used it to make timelines, chronologies, and charts to figure out the book’s structural skeleton — the major evidentiary discoveries, the twists and the red herrings, the whodunit reveal to the readers and the various characters. Eventually Miracle Creek took shape, and along the way, I learned a few key lessons:

Use as many POV characters as the story demands

In how-to books and articles about novel writing, I’d read that you should minimize the number of POV characters in order to maximize character depth, and that if you’re going to have more than one narrator, you should alternate the voices and have them take turns in some consistent pattern. But Mystic River defies those so-called rules. It has six POV characters (seven if you count a few scenes written in an omniscient voice), with no predictable pattern to which character speaks and when, no alternating back and forth or taking equal turns. Two characters narrate only a few scenes each, whereas one character takes over for almost one-half of the novel.

Before analyzing Mystic River, I’d agitated about who my three (or four, at most) POV characters should be. Which character in the immigrant family should get to talk about their collective experience? Which one of the mothers of kids with disabilities and chronic illnesses should be the group’s spokesperson? After my analysis, I felt free to go outside those boundaries and ended up writing from the perspectives of seven characters, giving me the room to explore the immigrant and the mother/caregiver experiences from multiple angles — the commonalities and the differences, the bonds and the jealousies. I had different characters step up whenever the story warranted without worrying about giving them equal space, which allowed one character to take over the narrative only for two scenes for which she had the most surprising insights (as well as the most critical information).

Narrators should be honest with the readers (but not necessarily with each other)

Another myth Mystic River debunked for me was that the first-person voice allows the most intimacy with the reader. The voices in Mystic River are mostly in close third-person, as close as any first-person narrative I’ve read, with each character speaking in a distinctive voice that reflects their personality and situation in life. The closeness also means that we get to eavesdrop on the characters’ raw, unfiltered thoughts and feelings. They do plenty of lying and keeping secrets from each other, but not from the readers. Any misdirection comes from the readers’ misinterpretations of whatever the characters are telling us, as well as Lehane’s careful decisions about which moments to highlight for the various characters — when he would cut away from one character, and to whom he’d turn.

I love the voices of Mystic River, so much so that I downloaded the audiobook on my phone so I could listen to it while driving, brushing my teeth, or doing the dishes, not necessarily even paying attention to the words, but just letting their rhythm and cadence seep into me. Before I started writing Miracle Creek, I spent six months just freewriting by hand the various characters’ stories, diary style, getting to know their voices and cultivating their distinctiveness. I ignored the temptation to follow the trend of using unreliable narrators who mislead readers. The mystery and misdirection come from the characters’ and readers’ mistaken assumptions and biases in interpreting what they’ve witnessed/read, as well as the choice of which characters get to tell which part of the story.

Explore the full ramifications of the reveal — not only to the reader but among the characters

In Mystic River, as with most mysteries, the detective discovers the identity of the murderer toward the end, at about the 90 percent mark. But Lehane does something more with the whodunit reveal: He takes advantage of the fact that not everyone solves the mystery at the same time. The major characters learn what really happened at different points than the detective/reader — some a little earlier, some as late as around the 95 percent mark — and the consequences of this timing discrepancy are as dramatic and tragic as the initial crime.

I don’t plot or outline before I write — I didn’t even know in advance who set the fire to the HBOT in Miracle Creek — but having Mystic River’s plot-point placements as structural markers helped to guide my writing and was essential during the lengthy revision process. In particular, I kept in mind this lesson about what could happen by virtue of the discrepancies between who learns what really happened and when, and to explore not just the direct consequences of our (and the authorities’) discovery, but the full reverberations on the whole community. As a result, many readers have told me that the most surprising part of the ending wasn’t the whodunit reveal, but what happened by virtue of the characters’ actions and inactions after they discovered the full truth.

Since Miracle Creek’s publication six months ago, I’ve connected with thousands of readers through reviews, social-media posts, and book-club Skypes. Some of my favorite comments are those that say they started Miracle Creek expecting a fun legal thriller but found it to be much more. Those readers stayed for the deep dive into the lives of immigrant families and parents of special-needs kids, both groups isolated and exhausted by the sacrifices they’ve had to make, desperate for connection. That was especially gratifying to hear, since for all the traits of Mystic River that I tried to emulate as a writer, it was that degree of immersiveness that I found most challenging — and rewarding.