Here’s the conundrum with The Anna Delvey Show: It’s unlikely the person being interviewed on the podcast is ever going to be as inherently interesting as the interviewer herself. Even the guests seem to know this — in fact, that’s probably why they showed up in the first place.

“You’re the first person I’ve ever hung out with who’s on house arrest,” said the musician Julia Cumming, a guest on the second episode. The installment broadly takes the shape of an interview about Cumming’s career and the modern music biz, but the truly interesting stuff only arrives whenever the conversation swings into brief diversions about Delvey, who’s making the podcast out of the East Village apartment where she’s serving that house arrest. You know, exchanges like these: “Are you allowed to decorate it?” “The ankle bracelet or my home?”

As you might know, Anna Delvey (or Sorokin) is the fake heiress who notoriously swindled gobs of money from several rich individuals and institutions by posing as a wealthy heiress. Her exploits made her something of a New York legend. And if you don’t actually know the story, don’t worry: There’s a feature in this very magazine, a book written by a former mark, a Netflix series produced by Shonda Rhimes, a so-so BBC podcast, and several news-magazine segments to fill you in. She’s either a folk hero or a prodigious con artist who indiscriminately messed with lives for personal gain. It’s probably some mix of both, and then some.

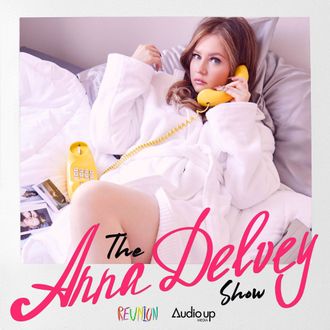

Anyway, whatever her deal is, Delvey’s tale has been abundantly documented in the media, but she hasn’t really communicated her side of the story on her own terms. Hence The Anna Delvey Show, because just about everybody has a podcast (especially if you’re famous), and Delvey’s contribution to the medium comes with a conceit that ties into her mythos: This is to be an interview show that moves “beyond tired notions of right and wrong” by exploring “preconceived notions of rule breakers, effects of adversity, validity of existing systems and status quo” with a series of guests who presumably have things to say about those ideas. You even get the full experience of Delvey’s famously hard-to-pinpoint accent, which, in hindsight, Julia Garner did an amazing job emulating in Inventing Anna.

At least, that’s the pitch of the thing. In reality, it’s more likely a gambit to circumvent the Son of Sam law, which was designed to prevent criminals from profiting off the publicity of their crimes, and financially capitalize on the mania around her story. In the age of constant reinvention via podcast, The Anna Delvey Show makes for a textbook public-relations play.

Listen, I’m not one to judge. I’m as fascinated with the Delvey mythology as the next person, and I happily dove headfirst into the podcast. But anybody going in with an interest in learning what Delvey really thinks about anything might need to modulate their expectations. “You should talk more,” said Whitney Cummings, who served as the show’s inaugural guest. The comedian’s advice comes around 46 minutes into the episode, which was about 40 minutes after the same thought crossed my mind. “You have an experience very few have,” added Cummings. “And the hardest part of doing this podcast, for me, is thinking, I really wanna know how she would answer this question.”

She never does get those answers. Throughout the episode, Delvey mostly keeps her own contributions to a minimum, moving the chat along in a manner that’s fairly common for novice interlocutors: lob a question, sit back, lob another question, sit back. As a showbiz professional, Cummings is game to fill the space, but c’mon, she already has her own podcast, and we all know why we’re here. Where Delvey does offer interjections, it’s usually in the form of asides about the media that one would expect from someone so publicly covered — “They’re just mad because they don’t have the power and influence they used to have” — or fleeting references to her time in prison, which, yes, is tantalizing in its generalities. This is probably a good display of how she was able to surreptitiously move through elite spaces: If the other person is always talking about themselves, how can they figure out your deal?

There is an obvious question to be asked of all this. To what extent is The Anna Delvey Show part of some bigger con? But it’s a boring inquiry. Of course it’s part of a bigger con. What is social-media celebrity if not an elaborate act of public performance and obfuscation for financial gain? At least, with the prospect of getting more insight into one of the weirder spectacles in recent memory, you might actually be able to get something back as the mark.