One of the first times that legendary character actor James Hong ever appeared onscreen was in 1955’s Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing, a tearjerker about the relationship between a half-Chinese, half-European doctor who lives in Hong Kong and a white war correspondent sent to cover the Chinese Civil War. It was based on the semi-autobiographical novel by the writer Han Suyin, and Hong was one of several Asian American actors in the cast, along with Philip Ahn, Richard Loo, and Soo Yong. But the mixed-race doctor character on whom the film was centered was played by Jennifer Jones, who was white.

It wasn’t the last time that Hong, the Minneapolis-born son of Hong Kong immigrants, would play a supporting role alongside a white lead in yellowface. Two years later, he was cast as “Number One Son” Barry in The New Adventures of Charlie Chan, a half-hour crime-drama series based on Earl Derr Biggers’s detective novels; Charlie Chan, Barry’s father, was played by the Irish American J. Carrol Naish. In the ’70s, while David Carradine starred in Kung Fu as the biracial Shaolin monk Kwai Chang Caine, Hong played no fewer than eight different one-off roles over the show’s three seasons. It wasn’t unheard of for a guest actor to appear as more than one character over the course of a series; Hong had done the same thing on series like I Spy and Hawaii Five-O. In Kung Fu, though, he once appeared as two different characters in episodes that were just a week apart.

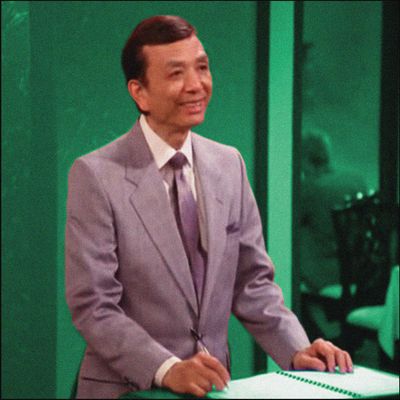

This was a testament to Hong’s versatility as an actor — and to producers’ assumption that their audience wouldn’t notice, or just wouldn’t care, that a solid chunk of a show’s Asian characters were all played by the same guy. But Hong wasn’t interchangeable, even if viewers didn’t know him by name. If in-demand character actors can be prolific, Hong is on a level of own; at the age of 92, he has over 600 credits to his name. Turn on any American TV show made between the 1950s and the ’80s — if there was a supporting part to be played by an East Asian male, chances are good it was filled by James Hong. He was Faye Dunaway’s stoic but devoted butler in Chinatown. The genetic designer who gets ambushed by replicants in his subzero lab in Blade Runner. The maître d’ who stonewalled the Seinfeld characters in “The Chinese Restaurant.” The ancient sorcerer in Big Trouble in Little China, leaning into the Orientalist tropes and making them gleefully absurd.

Some of the roles he took on were stereotypical, though as Hong — who co-founded a theater troupe called the East West Players in an effort to showcase Asian American work outside of the narrow Hollywood lens — pointed out to the Star Tribune last year, the alternative was to go unseen. “What could you do? Stop working? You had to take the roles that were given to you and do the best you can,” he said. “So even if I was playing a part that simply said ‘Chinaman’ or ‘Villain,’ I would put my heart and soul into that being.”

To be a character actor means accepting a degree of typecasting. The parts tend to be more simply drawn, if also potentially more colorful, relying on existing assumptions to fill in the gaps. But if you’re a character actor of color, that can leave you constantly grappling with the ways that typecasting can overlap with racial caricature — calculating how harmful or humiliating the part you’re being offered might be. And for decades, being an Asian American character actor seemed to simultaneously represent a ceiling and a devil’s bargain.

Until fairly recently, it was treated as accepted wisdom that stardom was off the table — that there wasn’t an audience for an Asian American lead, that viewers needed reasons for characters to be Asian American, that because of that, there would never be an Asian American A-lister. There were a few breakthroughs — Anna May Wong and Bruce Lee, Flower Drum Song and The Joy Luck Club — but they never seemed to lead to sizable change. (These breakthroughs were almost always centered on Chinese or Chinese American stories, too.) What was particularly perverse is that Asian Americans were also freely sidelined in material about Asianness. They were brought in to fill out scenes and lend an aura of legitimacy, but weren’t cast as the protagonists, even in their own stories. When MGM adapted Pearl S. Buck’s novel The Good Earth in 1937, Wong, a straight-up movie star at that point, campaigned to play the female lead. But she was never really a serious candidate: The lead was set to be played by Paul Muni in yellowface, and for Wong to act alongside the white actor would violate the Hays Code, which forbade depictions of miscegenation. The part went to Luise Rainer, and Wong was offered the role of the duplicitous concubine instead, which she refused.

In 2000, Joann Faung Jean Lee published Asian American Actors: Oral Histories from Stage, Screen, and Television, a book of interviews with East Asian American actors who were working, or trying to work, in California and New York. It’s very of its moment — the book limits itself to mostly Chinese and Japanese American subjects; it doesn’t touch on issues that come with, for instance, being both Asian and darker-skinned; it features repeated mentions of the Russell Wong series Vanishing Son. But it’s a valuable look at the kind of encounters and stories that are shared, and how much they still have in common with those Anna May Wong days.

One of the only people interviewed for the book who actually experienced fame was The World of Suzie Wong star Nancy Kwan, who spoke about the pushback she received from people who felt her breakout role fed into the impression that Asian women were passive and sexually pliant. It “sounds like an easy choice,” one of the interviewees, Ken Narasaki, said of steering clear of racist parts. “But there’s usually a big gray area, and everyone’s line of what he’ll step over and what he won’t is different.” (For him, that meant turning down a commercial where he’d have to dress up as a samurai and swing a sword at a price tag.)

For Fay Ann Lee, the tough call was also her big break — when she was cast as a chorus girl in Miss Saigon on Broadway. “I was like, I can’t believe this show. I mean, this is such a horrible stereotype of Asian women,” Lee observed. “You don’t reconcile the fact that it is a stereotype. You just live with it; you just accept it; you do it; you move on.” Some of the other actors had already realized their energies were best spent in theater, or quit the industry altogether after coming to believe they were never going to get offered roles that weren’t gangsters or grocers. Some of the subjects bring up martial-arts movies as a loaded way of achieving stardom, especially with Jackie Chan’s star rising in the U.S. But most of all, they talk about the idea of just playing a regular person, and how out of reach that kind of role seemed.

By the ’90s, the types on offer had started to change: the opium smuggler, sex worker, and bucktoothed nerd giving way to the businessman, the lab assistant, and the reporter. (You could map Hollywood’s slowly broadening ideas about Asians onscreen against James Hong’s filmography alone — from his characters whose every arrival was accompanied by a gong, to the doctors and sages he segued into as the years passed.) These benign parts had more dignity, or maybe just more respectability. But they also had a kind of texturelessness as what actor Billy Chang deemed “filler roles,” delivering exposition or prompts that allow more central characters to talk. As Chang put it: “They can’t show an area or a scene where there are no Asians in it but at the same time I don’t think they want to make them the center of attention.”

Conversations about the Asian American experience seem consumed with representation onscreen. Tracking progress in movies and on television shows — incremental triumphs of storytelling, stardom, and testaments to romantic viability — can feel like a preoccupation that comes at the expense of discussions about other, more tangible issues. But that screen history has also provided a reliable reflection of how Asians and Asian Americans have existed in the national consciousness, as inscrutable, as exotic, as monolithic, as untrustworthy, or as barely present at all.

Even as film and television have opened up, some old, ugly images remain. The shadow of so many fetishized and dehumanized sex-worker characters lingers over the Atlanta shooter’s description of the six Chinese and Korean women he murdered, as offered by Captain Jay Baker, spokesman for the Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office: They were “a temptation for him that he wanted to eliminate.” Resurging xenophobia recalls Hollywood’s repeated images of Chinatown as a dark warren of yellow peril. The difficulty the media has had covering the recent rise in anti-Asian violence feels related to that decades-old tendency to decenter Asian Americans in their own stories — a void in empathy, a failure of understanding.

For the Atlanta shooting to take place a day after actors were applauded for “breaking the bamboo ceiling” in the Oscar nominations just highlights the gap between milestones in visibility and the realities faced by members of a sprawling and far from monolithic demographic. Hollywood acknowledgment isn’t a proxy for the country as a whole, but a recognition that the industry sees bankability in certain kinds of Asian and Asian American actors and stories. Roles have been steadily, but selectively, diversifying over the past two decades: Lana Condor became a teen rom-com queen in the To All the Boys I Loved Before trilogy, Awkwafina a serio-comic lead in The Farewell. Greta Lee has carved out a place for herself as a sly scene-stealer, while Simu Liu is heading up Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings as the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s first Asian American lead. There are some new types emerging too: the sweet-natured doofuses like Josh Chan (Vincent Rodriguez III) on Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and Jason Mendoza (Manny Jacinto) on The Good Place, the rich people behaving badly in Crazy Rich Asians and its reality-TV children, Bling Empire and House of Ho.

In his recent novel Interior Chinatown, writer Charles Yu uses the idea of being a background player as an allegory for feeling near-invisible as an Asian American. His narrator Willis Wu works in the Chinese restaurant he lives above, just like his aging Taiwanese immigrant parents did. But he and everyone he knows also take on a revolving array of bit parts in an expansive police procedural that impossibly, always seems to be shooting. Willis is the Disgraced Son or Delivery Guy, the way his mother was Asiatic Seductress or Dead Beautiful Maiden Number One, and his father Egg Roll Cook and then enigmatic Sifu. While Willis longs for liberation from these reductive categories, he’s also so inured to the roles on offer to him as an Asian American man that he has trouble seizing the opportunity life offers him to escape them — to play, as so many of those interviewees in Lee’s book longed to do, a regular guy. He can only devote himself to becoming Kung Fu Guy, even though he ultimately has to acknowledge that is just another type.

Some of the most recognizable Asian American performers working now are character actors, or character actor–adjacent, and they mostly exist outside the boundaries of what James Hong refers to as “gimmick roles.” The possibility that they will one day be the center of the story is much closer — the potential for stardom, at last, within reach. It’s progress of a bittersweet sort, this acceptance within the values the industry has always prized; the greatest strides have tended to be made by performers who are beautiful, thin, and lighter-skinned. This long-incoming acknowledgment that an Asian American can be compelling, surprising, interesting, and funny is still recognition on Hollywood’s terms, still an invitation to participate in an industry that’s long been warped and broken. The next step should mean dismantling the industry’s idea of what it means to play the regular guy altogether — the idea that normalcy was ever aspirational.