HBO’s Bad Education tells the wild tale of former Roslyn schools superintendent Frank Tassone (Hugh Jackman), a beloved educator who hoodwinked a tony Long Island town to the tune of $11.2 million over a dozen years. Based on a true story reported in New York Magazine and adapted by screenwriter Mike Makowsky, who was a Roslyn middle-schooler when the scandal broke, the film rollickingly details Tassone’s duplicitous double life.

While elevating the affluent North Shore enclave’s public school system into one of America’s best, Tassone and his larcenous accomplice, school business administrator Pamela Gluckin (Allison Janney), were embezzling millions — taking more than $1 million in cash withdrawals and buying homes, luxury vacations, high-end cars, boats, jewelry, and artwork. After Gluckin was caught, Tassone finessed her quiet firing to save his own face-lifted skin. It was only after a local student reporter began digging into the real reason for Gluckin’s dismissal that the town learned what had been going on.

But to what degree is the film’s story true? Using the original New York account plus subsequent reporting, including the New York State comptroller’s audit — which could only account for about $7 million of the missing money — here’s a character-by-character guide to instruct you.

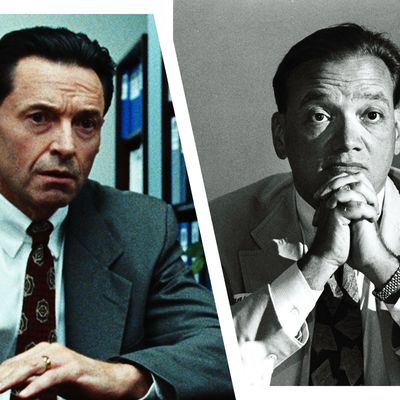

Hugh Jackman as Frank Tassone

Like Hugh Jackman’s would-be widower, the real Tassone — a double master’s- and doctorate-degreed Bronx native — worked diligently for a community whose sense of entitlement is as inflated as the prices at the Kitchen Kabaret store we see as Bad Education opens. Deciding his worth was as high as those he served, Tassone helped himself to $2.2 million for rent on an Upper East Side apartment he shared with his longtime partner, Stephen Signorelli, a country home, trips, parking garages, and dry cleaning, among other expenses. He also owned a Las Vegas home that he shared with a second boyfriend, Jason Daugherty (who inspired the film’s Kyle Contreras character, played by Rafael Casal). As Bad Education notes, Tassone still draws a pension of $174,035, even after pleading guilty to grand larceny and serving about three years of his four- to 12-year prison sentence. Tassone returned $1.9 million in 2006 and promised to repay the rest. He was released from jail in 2010.

Allison Janney as Pamela Gluckin

Like her real-life counterpart, Allison Janney’s affable school administrator earned about $160,000 annually and was brazen enough to drive a car with personalized “DUNENUTN” plates — a nod to the West Hampton beach house the district unknowingly paid for. As in the film, $223,000 of Gluckin’s bills, including for her son’s building supplies, led to her dismissal and relinquishing of her administrator’s license in 2002. Arrested in 2005, Gluckin admitted in 2006 to absconding with $4.3 million for a lavish lifestyle that included two more district-funded homes in Bellmore, New York, and Hobe Sound, Florida. She ultimately struck a plea deal, got a three- to nine-year sentence, and spent nearly five years behind bars while still drawing her annual $54,998 pension (half of it went to Roslyn’s restitution). According to HBO, Gluckin died in 2017.

Ray Romano as Bob Spicer

Spicer, a local real-estate agent and big Tassone booster, is a fictitious stand-in for the community at large. In a place where appearance is everything, Spicer is blinded by Roslyn students’ increased acceptance to top-tier colleges — and the soaring real-estate prices that benefitted the town’s bottom line, a.k.a. higher taxes! William Costigan, whom the New York Times described as “a close ally of Tassone’s,” was school board president in 2005, when a new assistant superintendent began discovering the true depths of Gluckin’s scamming.

Annaleigh Ashford as Jenny Aquila

Though Bad Education gives her a different name, Gluckin really did install her niece Debra Rigano as a district clerk — even bestowing a salary beyond what was budgeted. One of the younger Rigano’s responsibilities was arranging school board members’ trips to conferences, including Tassone’s boondoggles. Her freelance work as a travel agent garnered her commissions on the district trips she booked. Jenny’s petty video-game and Macy’s and Lord and Taylor purchases pale in comparison with the approximately $780,000 that Rigano ultimately admitted to stealing. After cooperating with prosecutors, she was sentenced to two to six years in jail.

Geraldine Viswanathan as Rachel Bhargava

Bhargava is a stand-in for real student-reporter Rebekah Rombom, one of two editors-in-chief of the high school paper The Hilltop Beacon. Rather than a puff piece evolving into the scoop we see in the film, a tip led to Rombom breaking the story about the real reason for Gluckin’s 2002 exit, though she wasn’t allowed to print her name. She likely obtained the information from a 2004 anonymous letter that began circulating and for which Tassone tried to do damage control. Once the Beacon story broke, Newsday and other newspapers began digging into the scandal that became the biggest school fraud case in the country.

Jeremy Shamos as Phil Metzger

Like Metzger in the film, a real Roslyn accountant named Andrew Miller conducted an audit and found about $250,000 went to Gluckin’s profligate spending. As with Metzger, the auditor let the crime go unreported and was brought back at Tassone’s urging years later after the D.A. got involved. Miller was ultimately charged with cooking the books to conceal millions of missing taxpayer money. He pleaded guilty to a felony and received a four-month sentence and 18 months probation.

Stephen Spinella as Thomas Tuggiero

The loyal Tuggiero hews closely to Tassone’s real domestic partner, Stephen Signorelli. The computer consultant was listed as the CEO of a company that submitted fake printing invoices for over $500,000, more than $200,000 of which he passed on to Tassone. Signorelli pleaded guilty to grand larceny in 2006 and was set to serve at least a year of his one- to three-year prison sentence.

Jimmy Tatro as Jimmy McCarden

The parallels between Jimmy Tatro’s construction contractor and Gluckin’s real son John McCormick are pretty accurate. McCormick’s home-center spending spree was indeed what led to the unraveling of his mother’s scamming in 2002. But rather than a tip from the cousin of the school board president’s wife as the film depicts, it was an eagle-eyed Home Depot salesperson who noticed McCormick was using a Roslyn district credit card. In 2006, McCormick was sentenced to five years of probation and 100 hours of community service for stealing $83,000. Were it not for that imprudent act, who knows how long Tassone’s and Gluckin’s greed could have continued undetected?