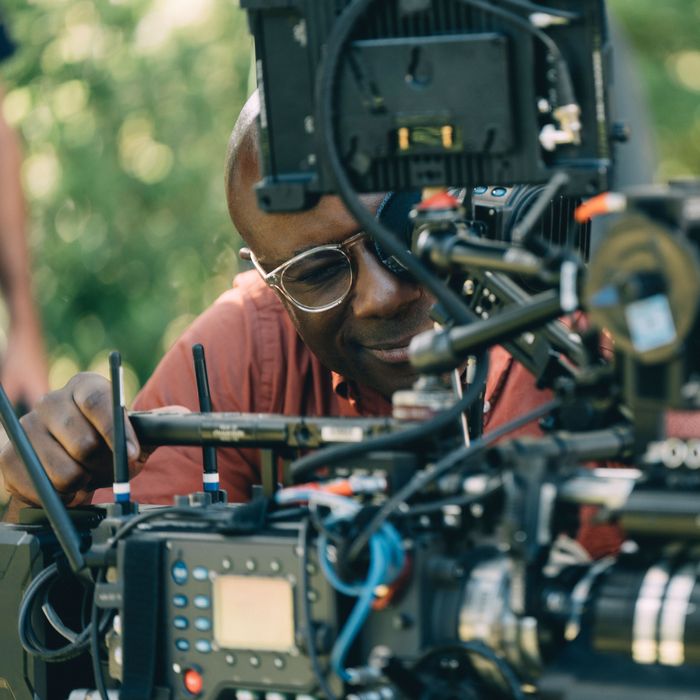

Writer-director Barry Jenkins is known for telling stories with aesthetic daring and more than a touch of poetry. In Medicine for Melancholy, the multiple-Oscar winner Moonlight, and the James Baldwin adaptation If Beale Street Could Talk, Jenkins took viewers deep inside the experiences and emotions of Black American characters, using a range of subjective and objective filmmaking techniques drawn from more than a century’s worth of American and international cinema. Jenkins’s Amazon miniseries, The Underground Railroad, is his most ambitious work to date, telling a ten-part story drawn from Colson Whitehead’s 2016 Pulitzer-winning magical-realist drama.

Rather than a straightforward, literal-minded transcription of the book, Jenkins and his collaborators worked intuitively all through the production, creating a historical dream and nightmare. They made bold decisions on the fly, drawing on scripture, myths, legends, paintings, and their own instincts about how to visualize the emotional interiors of the main characters. Recently, Jenkins and I parsed those decisions over the course of two separate wide-ranging discussions, considering the advantages and limitations of longform storytelling, the use of subjective filmmaking techniques to get into characters’ heads, the interplay of image, sound, and music, and the pleasures and dangers of letting your unconscious guide you.

This series is the largest production you’ve done in terms of both budget and duration. Can you talk about how the challenges differed from those of a self-contained film?

The biggest challenge was just prepping everything. You know, I spoke to [True Detective season one] director Cary Fukunaga, I spoke to [The Knick director] Steven Soderbergh, before going down to Georgia to start production. And they both said that it’s humanly impossible to keep that much information in your brain at once. And it’s humanly impossible to prep five, six episodes in advance. Cary said you can maybe get away with five, and he felt like even that was mentally fatiguing. He said, “Imagine your brain is a hard drive. You run out of capacity.”

So you kinda have to wing it?

Yeah, after a certain point. It wasn’t until I was in the middle of it all that I realized exactly what Cary and Steven were talking about.

Did you seek out Colson Whitehead’s book, or was it a project that was brought to you?

Oh, I sought it out. I was a big fan of Colson’s from way back. And when I was a kid, I was fascinated with the Underground Railroad. When I heard the phrase, I just saw Black people on trains underground.

I think everybody did.

Exactly! And so when I heard the concept of the book, I thought, Oh shit, he’s a great writer, and I’m pretty certain there’s gonna be something in this that I’m gonna want to apply my voice to. And I was right. It actually happened before Moonlight premiered at Telluride. I read the book and was like, “Yo, we gotta get the rights to this.”

I would imagine that nailing the tone was tricky because you don’t want to minimize the horrifying reality of what happened in this country, and yet you also have this fantasy element. This is not reality per se, but a fantasy or dream about it.

It’s not a fact-based depiction of history, but I think it is in some ways a truth-based depiction of history, if that makes sense.

Do we ever learn what year it is?

No, we don’t. When we were in the writers’ room, I thought, I could call up Colson and go, “I need a map. Like, I need a time map, and can you explain to me what you’re doing in this book?” But then I thought, You know, you don’t have that kind of map when you’re reading the book. So much of this process for me was about, I want the experience of viewing this to be not literally my experience of reading the book.

You didn’t want to make a slideshow from the plot of a novel.

That’s right. I don’t want the viewer to have to put up with something like that! And that’s why I ended up not asking Colson for an actual, bibliographic, temporal road map for our journey.

The novel is not a literal-minded story.

No, it’s not — it’s extremely figurative, that’s for sure. And what I do love is, because he’s taken that approach, you’re not confined between the years of 1850 and 1860, which is a very particular experience for Black people in America. Instead, you know, at one point you have these skyscrapers, and it seems like you’re in Jim Crow, and it’s a very genteel Jim Crow.

I was gonna ask about that. There’s a skyscraper in episode two, the South Carolina episode. The first skyscraper was built 20 years after the end of the Civil War, and it was built in Chicago, not South Carolina.

Exactly.

So Colson is playing with all these different things at the same time, mixing them all together, and that allows me as a filmmaker to go, Every time this woman moves to a new state, it’s a completely different tone, a completely different genre. You know? Now I can apply a different aesthetic, both a different sound aesthetic and a different visual aesthetic, to how we’re relaying this information to the viewer.

In the way that the ten chapters of the series are broken down, it seemed to me as if each one was almost less like the chapter of a story than a separate philosophical or artistic prompt having to do with the idea of American slavery.

How do you mean?

Take the second episode, set in South Carolina. South Carolina never decided, straight up, “No Black people are going to live here — ”

But Oregon did.

But Oregon did …

But Oregon did — but Oregon did. And so the [white] people are dressed the way Oregon frontiersmen and women would have dressed in the 1830s. Also, in the South Carolina episode, the Black men are dressed in the way that Black men in Congress dressed during Reconstruction, and the women are dressed the way they would have dressed in that time period as well.

When you’re creating a historical gumbo like this, how do you keep a handle on the details? They’ve got to be rooted in something.

We did have very concrete references for everything in every episode of the show, but it’s not all front and center, and we’re not blasting it to the audience. We had to have concrete references for the crew because the biggest difficulty of making something at this scale — 500 pages of script and 116 [shooting] days — is that the people working on it need to have some sort of anchor. You know? Okay, Barry, cool, this is where this state is operating from. Okay, great, now I know which fabrics to pull. Now I know the way the hair should be styled, how I should carry my shoulders — all these different things. So we did have to map out some stuff. But a lot of it’s just driven by instinct.

Speaking of the aesthetic: Is there an internal logic, any sort of process, that you apply to decide what violence to show, how to show it, for how long, and at what distance?

Yeah. For starters, it depends on how crucial the violence is for the character, especially the main character.

But before we get too deep into it, I should start by telling you here that I had to have my own moral and ethical reckoning with each of those scenes in the first chapter of the book and the show. As we were talking about earlier, most of this is fiction, but that chapter’s rooted in fact. By which I mean: These things happened. I’ve seen photos of the aftermath of events like that from the Jim Crow era, from the Jim Crow South. When there wasn’t photographic evidence or other pictorial witnessing, those things that happened might have been even worse.

Our main character in the show, Cora, is a woman who has just given up on everything. She’s been abandoned, she’s born into slavery, she’s very bitter and angry, and she feels a bit worthless. And so when this guy comes and says, “We need to leave,” she tells him no. It takes an extreme act to push her to the point where she decides, “You know what? Actually, yes, you’re right — we must go.” That act was a public, brutal, horrific immolation of one man, Big Anthony. That’s why I thought it was so important to dwell on that particular incident.

I think also, having grown up and seen so many of the aftermaths of that image, we’ve in a certain way allowed ourselves as a country to shirk the responsibility of the full weight of some of these happenings, of these lynchings. And I thought that right now, as far as plot motivation, and in terms of all the other factors we’re talking about, it makes sense this moment needs to happen, in the first episode, and that in order for the audience to truly understand like how grave the scenario is, how entrenched this character is, and what it takes to dislodge her to the point that she will risk everything, it must be shown. I mean shown.

How was it staged and filmed? What were the technical aspects, and how did they intersect with these ethical considerations?

It’s interesting, the technology. Filming the sequence, there’s no blood, there’s no fire, of course, and the actor’s on a stunt harness. The visual effects are very good. They could have been better, but there was a point where I realized, That’s enough, we’ll stop.

And to be clear, by “better” I mean that the level of realism could have gone even farther. The thing I wanted to be extremely real is this man is being hung up by his wrists, and he’s being attacked by this whip. And we often see these photos of the formerly enslaved, and we see the healed wounds on their back. But we’ve never been allowed to see what happens if you suspend a 300 or 250 pound man by his wrists and serrate his flesh. That’s going to do certain things to that flesh, and I have never seen those things. To understand the absolute brutality of what the system of American slavery was, I wanted to show very organically what that process would look like.

And so I made the choice: This is going to be the place, this is going to be the time, this is going to be the one image that I’m not going to look away from. If the audience wants to look away, they can. But I cannot allow them to deny the fact of this image.

Earlier in the episode, when the two characters are whipped — there are only three instances of whipping in this entire show, and there’s no moment when you see a whip contact flesh and then blood comes off. You know, we always kinda hide the whip. We filmed that scene in a great big wide shot at night, intentionally, and on set, the first shot we did was the wide. I thought, Let’s start wide. Let’s see how it feels, then figure out what else we might need for the scene.

After the very first take, I realized, We’re done. That’s all we need. You know? We’re not getting any closer than this. Not at this moment.

And then I thought, What remains to be excavated from this image? Because if we’re creating this image, it’s gotta be adding something to the conversation around images like this. And then I thought, Okay, let’s come off the acute trauma, and now let’s find the way this trauma metastasizes among this group.

Time and again, you begin a violent scene by showing us an act from a distance, or partly obscured. And then you very deliberately move the camera so that we see spectators reacting to the violence. And that is where you settle and stay: on the witnesses.

Exactly! Because to me that’s the entire point. That’s the point. You know, I think we have to bear witness, and we were forced to bear witness. This is how the aggrievement of one becomes a trauma shared by all.

The question that intrigued me here was “Can you own trauma?” I thought that was an interesting concept to investigate. To explore this idea of witnesses, of witnessing, of what it means to witness. To bear witness. There are witnesses everywhere in this story, all throughout the show. And there are certain points where we take this act of witnessing, and we give it a … [Pause] I don’t know, Matt. This idea of “witnessing,” you know, you’d assume that goes one way, in the sense that the trauma of one becomes the trauma of many. But that is a way of almost giving the trauma an elevated degree of power, or an outsized degree of power. And that brings me to this other, related idea, which is: I think this other act of witnessing too, of seeing other folks’s endurance, and their resistance, can take away some of the power of that trauma as well. As the show goes on, moving past that first episode, we really do try our best to accomplish something like that.

But right off the bat, in the first episode, the Georgia episode, there’s no doubt about it. I mean, that shit is real. It had to feel real.

In the Tennessee episode, you have a runaway slave, Jasper, who says to the slavemaster Ridgeway, speaking of God, “He’s gonna look at you and see what you’ve done.” That jumps out at me, in light of what we’re talking about here: the act of witnessing and what it means to bear witness.

Go on.

One of the shots you’re identified with is the close-up where a character is not quite looking into the lens, but almost.

Wes Anderson, who also loves that kind of shot, calls it “a Demme,” as in Jonathan Demme, who popularized it, but of course Demme wasn’t the first to do it. Jean-Luc Godard did it before him, and you could argue that the shot goes back to Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, and maybe even further, to The Great Train Robbery, where a cowboy fires his gun into the camera. I feel like there’s an implicit challenge to that kind of close-up, even though it’s benevolent when you do it. The character seems to know they’re being looked at, by another character or by the audience. You feel as if they can see us or maybe just feel our presence as we’re looking at them. And here’s where I’m going with this: we get to chapter four, “The Great Spirit,” the episode about Ridgeway’s relationship to his father. Ridgeway the elder tells his son —

“Look into every man, into every man, and search for yourself there.”

Yes. That’s it! That’s where I was going! I feel as if it’s about looking and being looked at, and it’s all connected. Or am I assuming too much?

No, no, no, you’re not, you’re not. It is all connected. What I loved about the process of making the show, what I loved about making not just necessarily television, but making this ten-episode thing, was how organically those things began to happen. You know, the line that you’re so interested in here, from “The Great Spirit,” that one’s written very intentionally. But the other line you mention, about how he’s gonna look at you and see what you’ve done, that one kind of just happened, you know? It kind of just happened, it kind of came to me. And it wasn’t about referencing the lines of Ridgeway’s dad and the mini-episode. It was about that character, Jasper, having possession of himself, and not being afraid of Ridgeway, and in some way being on this spiritual wavelength, you know, that for Ridgeway is a thing his own father didn’t see in him, but that he did see in all these Black folks. And it was a way of giving Jasper this dagger that he could stick in this dude and just … [Mimes twisting a knife.]

Right, right.

And it’s a double entendre because it could be that God is going to look at you and see what you’ve done. He’s kneeling before a Bible. He’s praying. And we don’t cut to the Bible. We have a shot at the very end of that scene revealing that what Joel [Edgerton]’s looking at is a Bible sitting there on the altar, but I didn’t want to be too too with it, you know?

Too reductive, too obvious.

Right. We didn’t want that. And of course, as Jasper says that, he has no way of knowing that Ridgeway’s father said that to him. [Laughs] But maybe he does know, man. Maybe he does. So much of this shit was so … [Gestures at the air above his head, laughs again.]

Guided by the Great Spirit?

Maybe, man. Maybe. Did you know that the two-parter about Tennessee was meant to be one episode?

No. Why did it end up being two parts?

I had this joke on the set where I said to James [Laxton, Jenkins’s longtime cinematographer] and our camera operator, this guy Jarrett Morgan — who I nicknamed the Possum, because he was able to just worm his way into all these amazing spots — I told them, “I want to put these editors out of work. I want them to have nothing to do.” By which I meant, whenever possible, rather than cutting to a new shot all the time, I wanted to try to create a new shot by moving the camera. Not that editing is artifice, but I do think that when you can stage an event as one continuous moment in time, there’s a veracity to the result that just can’t be denied. You see it and go, Holy shit, that thing happened right then — right there in that space between those people.

And so I was always looking for ways to not have to cut to a new setup, not to have to reset the camera. Instead, let’s move to a place where now we have some new information, we’ve created a new moment, one that has been evolved out of the moment that began the scene or began the shot.

All of which leads me to this, Matt: The actor who plays Jasper, this guy Calvin Leon Smith, he just showed up, and he was just so … he was just so fully himself. And so we were filming the episode, right, and we’re shooting the scene where they’re in the back of the wagon, and the camera floats over Homer sleeping, and then it comes in over the back of the wagon, and it rotates, and it lands on Cora, and she starts talking to all these people that have passed. Now, I wish I was stronger in the edit, because that is one unbroken take. We don’t have to cut to the people she’s seeing in order to make the shot work, even though we did, because it’s one shot, and it’s beautiful. Anyway, we shot it on location, 35 degrees outside, at night, the camera comes over Homer, pirouettes, sits on Cora. Every time she speaks to one person, the camera gets a little bit closer to her, a little bit closer, a little bit closer. And then it lands, and you almost forget Jasper was there ’cause she forgets he’s there. And then he takes the power, he pulls the lens to himself when he finally speaks, ’cause he hasn’t spoken to her the whole episode.

What did it feel like, shooting that moment?

It was just like, Ahhhhhhh. We winged it, man, and it fucking worked. And I was like, Ahhhhhhh.

And then we just kept finding moments like that during the shooting of that episode, and finally, we sat down to edit, and I was like, “You know what, Jasper has created his own episode here. Let’s give him one. This is a full hour built around Jasper, and then they’ll arrive at the compound, and that’ll be the second hour.” Because I can’t have Ridgeway overwhelm what this man is doing for Cora — you know, the example that he’s setting. And the performance that Calvin is giving.

I felt all this so much when we were shooting that later, as we were editing it, we had Jasper take his last breath and then [breathes] we cut to Cora as she comes up out of the water.

It’s not that Ridgeway saves Cora. We don’t have that implication. Instead, because of the cut from Jasper’s last breath to Cora and Ridgeway coming up out of the water, now I think there’s a sense that there was some kind of spiritual transference. That’s what comes across now, I think. And that’s all because of Jasper — specifically because of what Calvin was bringing us with his performance as Jasper.

That’s the kind of shit that happened during the making of this thing, Matt. That kind of thing that happened to us all the time. All. The. Time.

So you find these connections, or you make these connections, on the day. Like they’re hiding out in the woods.

Exactly. You know, to say that the process is like jazz is a bit of a cliché, but it was this, this — [holds out both palms as if to indicate a feast laid out on a table] — it was a very responsive approach to the idea of “What is our aesthetic?” We had to always respond to questions like “How is the light today? What are the actors doing today? What is the best way for us to capture them that fits with the story we wanna tell?”

Can we talk about sunlight?

Sure, what do you wanna know about it?

You have always used sunlight in a deliberate, kind of metaphorical or poetic way in your films. But here, you really, really crank it up. Sometimes it reminded me of Steven Spielberg and Terrence Malick, two of the Sun Kings of cinema, what you do with the sun in this one.

What’s going on here? Can you say?

So much of this is about this idea of the Great Spirit. We even had a light on set that we refer to as “the Great Spirit light.” We only brought it out for particular moments. But that was an idea that, in the making of the show, we wanted to embrace. It almost felt like people were being baptized in light in a certain way.

There was this argument that I anticipated having about whether a sunlit image is too beautiful for the darkness or the horror or the brutality of the story. But we filmed the show entirely in the state of Georgia, a place where the condition of American slavery was allowed to run rampant, and Georgia was fucking beautiful, you know? I felt it would be almost untruthful or in poor taste to try to remove that beauty in the search for some sort of verisimilitude or gravitas. It would be a lie.

And so we decided to embrace it. And, to be honest, use it. Not as a specific symbol and not not as a specific metaphor, necessarily, but as a way of showing that there were all these rampant examples of natural beauty, of the ravishing beauty of the Earth, of the land being so beautiful and my people also being beautiful — and yet, despite all that beauty, all these horrors were still allowed to manifest. All these horrors were still actively visited upon us.

But there can’t help but be a metaphysical aspect to the use of sunlight in a story like this one. There were times when I felt as if the Great Spirit Light, if we can call it that, was backlighting people, or putting a halo around them, in a way that said to me, This is a person with a soul, or There is more to this person than flesh.

Definitely. In the sequence with Big Anthony, there’s a moment when the camera dollies behind him, and he is ringed in this almost spiritual piece of sunlight. When Cora and Royal have their apology scene in the field early in the second Indiana episode, they’re ringed by the same light.

And when you’re underground, in the railroad tunnels, and the light of the approaching train falls on characters, it’s not accurate to what that kind of light looks like in life. It’s an orange-brown color. It looks like the light cast by a rising or setting sun.

Exactly.

I find this fascinating.

I do, too! But at the same time, I also wanna say that I feel that to associate sunlight, or that sunlight color we’re talking about, or that feeling of sun, with one kind of image and not another kind of image would have been false for us when we were making this. It would have been us creating a certain thematic or symbolic association, or a subjective position, as far as what this light means, or what it should mean.

For the viewer?

Yes. And we didn’t want to do that.

So you want people to bring their own associations to it.

That’s it, exactly.

Can we talk a little bit about the use of sound? It’s simple and direct but densely layered, and it seems to comment on the action as often as the visuals do.

The use of sound came out of a sense of limitations. We’re making this show for a smaller screen, and that has certain deficiencies. I just know there are certain things that James and I are trying to do with the image that just won’t have the same kind of thrust, the same power, on a small screen, especially in the Tennessee episode, which we knew we were committed to filming wider than the others, even though it’s gonna play on a small screen. Most people don’t have projectors of the quality you’d find somewhere like the Angelika [Film Center]. But most people do have a speaker system or headphones or earbuds that are good, so we thought sound was a place where we can really be immersive.

We started doing field recordings of sounds even before we got to location to film the show. [Recording and supervising sound mixer] Onnalee Blank and [rerecording mixer] Mathew Waters already had people out recording bugs and birds and all of these different things. We wanted to put the viewers in the heads of these characters in terms of not just what they were hearing but what it meant to them.

What about the way that the sound of the bellows in the blacksmithing scene resembles the noises the locomotives make in the underground railroad? And the way that Nicholas Britell’s score sometimes seems to echo those types of noises?

The bellows happened organically, man. We had a blacksmith adviser on the show who always brought me this bison jerky. It was so damn delicious. And one time, he was teaching people how to work the anvil, and it just made this rhythm. Once that rhythm got into my head, I had to record it and send it to Nick [Brittell].

There was also a construction site next door, and when I heard the bass in their drill, I’d record that and send it to Nick. Or, you know, a certain bug was doing something: record that, send it to Nick. Or I’d hear bells and record them and send them to the sound department with a note like, “What about this? Do you think this could be a thing?”

Is there an aesthetic philosophy behind treating natural sound, created sound, and musical score as equal voices in the production and getting them to talk to one another and sometimes mimic each other?

Where that manifested itself was my going through the story and trying to contextualize what it must’ve been like to have been my ancestors. I realized that even though their bodies were constrained, their minds must have been incredibly robust ’cause you can’t control what a person is thinking or what a person is hearing. And then I thought, Oh, their hearing must have been extremely attuned.

You know, this is in some ways a way of communicating. See, the language, the English that we were taught and that we were allowed to use — most plantations didn’t allow us to speak in whatever our original language was — was English for instruction. English was giving and receiving instructions, not for communicating, you see what I’m saying? But my people, I’m sure, were listening. Did that person yelp? Is that person singing? I heard something — what is that? Is it a natural sound or is it a threat? You know?

And so it felt like the soundscape was another way to really identify with the main character — with what she’s feeling. Mat and Onna, they worked on Moonlight, and If Beale Street Could Talk, but they really know the medium of television because they worked on Game of Thrones, man. They did sound for Game of Thrones.

Well, that’s really all you need to know!

Exactly! So yeah, I was like, You know what, I’m gonna lean on y’all. And there were a lot of places where they were right on the money. And there were other places where we had to come together and go in a different direction.

Can you give me an example of the second thing?

In the last episode, the Mabel episode, I said, “We’re building toward a psychotic break here. So I need to be so in her head. This is not a documentary; this is Rosemary’s Baby.” So they did a pass on that and then we threw everything out the window, and we started over again from scratch. The main thing I was trying to get across was: We can take some chances here. We can be very aggressive here.

There were parts of the soundtrack where it seemed as if Nicholas Britell’s music was deliberately mimicking or echoing things that were happening with the sound effects. Your description of the sound design makes it seem like that’s a regular part of collaboration between you two.

It is. And it goes both ways. There are moments in this one where Nick is mimicking Onna and Mat, and there are moments where they’re mimicking Nick.

It sounds organic and intuitive, this process.

You have to give yourself over, and I mean give yourself over, to the material on a project as big as this. Because you gotta shoot six-to-seven pages every damn day. No matter what! Every damn day. What happens is what happened and what you made out of it happening.

My father was a jazz musician. Whenever anybody asked him what jazz is, he would say, “Jazz is a record of what happened in the room.”

Yes! That’s exactly what I’m trying to say to you. This show is a record of what happened in the room.

Can you give me an account of a time when something magical happened in a room, so to speak?

One of my favorite scenes in the whole show is in this same Tennessee episode. It was one of the most successful experiments in the making of the show. It kind of proved the aesthetic. This idea of trying to capture these extended moments in time that weren’t just still. There’s a scene after they go to the yellow-fever camp, after the “He’s gonna look at you and see what you’ve done” moment — there’s a scene where Ridgeway and Homer are standing by this piece of property that had tidal flooding. At the end of certain days, the water would come in, and the sun would set over that field, and we’d get this mist. And I said to James — on the day that we got there, ’cause most of these locations we shot for one day — I said, “Yo, if we get ahead of schedule, I’m pretty sure we’re going to want to take at least the last half hour, 20 minutes of the day, and we’re gonna do something over there. And James said “All right, cool.” I said, “And I think it’ll just be two cameras. Put the 50[mm] on the crane and get Possum on the Steadicam.” And he’s like, “All right, cool.”

“Possum.”

This kid is so good. He embraced the nickname Possum, He’s shooting Atlanta for Donald Glover right now ’cause that’s where we got him from, and even the crew there is calling him Possum.

So Possum got on Steadicam, James got up on the crane, and we got about two-thirds of the way through the day, and it was clear that we were gonna make it.

Is this the scene where Ridgeway dangles the key?

Yes, when he dangles the key. That’s the best shit, man, that shit that you just pull out. That’s André Holland smoking a cigarette in Moonlight outside the cafe. We’re wrapping up the day, and have the equipment on the truck, and I look at him and I go, “James, bring the camera. Let’s get one last shot.”

In this way, it was like making my first feature, Medicine for Melancholy. “Oh, my homeboy’s girlfriend is gonna let us use her apartment. This fish tank is incredible — why is that?” “Oh, because my boyfriend is the No. 2 aquarium guy in the whole Bay Area.” This was the same damn way!

Give me another example of that — another fish-tank moment, I guess? I love this.

Another fish-tank moment is when Cora goes into the hub at the end of the first Indiana episode. I knew I wanted Cora to go somewhere. Maybe it’s a childhood-wish fulfillment, but I wanted to see it. I wanted to see what this place was. I wanted to see the promise of all these Black folks together, but I didn’t want to break what’s already a very tenuous contract with reality. So I knew it had to be a dream.

So. We get to Macon, Georgia, to scout that episode. I’m really hungover the day we scout that location because we had just wrapped the Indiana episode and we’d all gone out for drinks. The next morning, I’m scouting, super-hungover, and I walk in this little back room, and there’s a window with very diffused light. I go, “Man, it would be trippy if she walked in here.” And Mark Friedberg, the production designer, goes, “Yeah, it would be. Let’s do it.”

And you did it.

[Laughs] We did it!

I’ll give you another story like that: Joel is so good in this show, and he was such a pleasure to work with. When we’re filming the big action sequence in episode nine — that was one of the few sequences that we storyboarded, like, from beginning to end — Joel walks into Royal’s cabin. Royal’s holster just happens to be there on the chair. And so he reaches into the holster, and without me telling Joel to do this, Joel picks it up, because he’s in character, right? And he puts it in his waistband, and he walks out. Unplanned — he just did it! And the moment I saw Joel do that, I realized, “That gun is going to travel.”

But because we were in that room, all of us, with Joel, of course we were wondering, “What should we do here? Should we be like, ‘No, no, Joel, don’t take that gun, that’s not the way it’s scripted’?” No. Hell no! I gotta say, “Take that gun, Joel. Take that gun and then I’m gonna go home tomorrow, and I’m gonna get on my laptop and figure it out, find some way to make sure we can thread this thing all the way through to the end, because it’s organic and fucking beautiful, man. Beautiful.”

And so the gun travels. It travels. It travels in his waistband, he’s going to take it all the way, he’s going to shoot Royal, pick Cora up off the ground, then he’s going to be getting ready to go down the ladder, but he can’t go down the ladder with two guns, and so he hands Royal’s gun to Homer. And then when Homer goes down, Homer sets the gun on the ground. And then Cora is coming down with Molly, she’s about to take that rifle, and what does she see? Her lover’s gun. And what does she kill them with? Her lover’s gun. She kills him with her lover’s gun!

I would never write something like what we did there. Never.

Your creative process on this show sounds like a chain of dominos falling.

It can feel like that, for sure. But like your dad says, this is what happens in the room.

It’s a challenge, too, right? When you commit to something like letting Ridgeway keep the gun, you’re daring yourself to figure out how to solve a puzzle that you just created. What happens if you can’t solve the puzzle?

Oh my God. Yes, that was the problem. That was the risk. We didn’t shoot in sequence, either. You hope it works out.

It’s interesting how often you seem to discover metaphors within images while you’re shooting on the fly. That’s a gift.

This show is an adaptation, and so a lot of the metaphors are baked in. But yeah, it’s true — some of that stuff you can’t account for. It’s mysterious.

Moonlight’s a perfect example. A storm is coming in, and we got to get the swimming scene in. So all the scripted dialogue we were gonna shoot that day goes out of the window. It’s like, “We only got about 45 minutes here before all hell breaks loose on the shore. What are we gonna do? All right — just teach him how to swim. Keep the lens above and below the water. Let’s go.” Boom. Go with God. You know?

It’s important to remember: We aren’t adding that sort of stuff. It’s already there. It’s there, man. It’s all around you. You gotta try to see it and seize on it. You gotta be able to use what’s in front of you. If you can bend — don’t break, but bend — you can find a way to do some interesting, interesting stuff.