We use all kinds of adjectives to adapt our expectations of genre, to give wiggle room to creators who want to push established narrative structures into unusual places. Elevated horror, cerebral sci-fi, the inclusive rom-com (because deviation from decades of whiteness and heterosexuality qualifies as a twist) — these descriptors both reinforce the tropes inherent to the genre in question and clue us in to how the project varies from those conventions. But sometimes a modifier loses its effectiveness, which is where we land with the “dark comedy” description of Barry. In its concluding act, Bill Hader’s series about the titular assassin turned actor reaches subterranean levels of bleakness, and a couple of unexpected line deliveries and zany set pieces can’t right that imbalance. That’s not a wholesale criticism of what Barry ends up doing, but it is a plea for comedies to be, you know, comedic.

Barry has been tracking this way for a while. This is a series about a former Marine and the people in his life — aspiring-actress girlfriend Sally (Sarah Goldberg), father-figure acting teacher Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler), other father figure and handler Fuches (Stephen Root) — lying to themselves about who they are and to one another about what they want, with their neediness and lack of self-awareness poisoning the people around them. Barry has killed dozens of people, Sally uses her own ambition as an excuse for cruelty, Gene was a bully when he was famous, and Fuches is a bully now. How do we process awful things like abuse, war, and negligence? And if we don’t, how do those experiences fester into damage we pass to other people? The series centered that question in a third season that ended with Barry captured for the murder of Detective Janice Moss (Paula Newsome) by Gene — who dated Janice — and her father, Jim (Robert Wisdom), and Sally disgraced after a video of her berating her former assistant went viral. Those feelings of insecurity once drew Barry and Sally together, but recognition isn’t the same thing as healing.

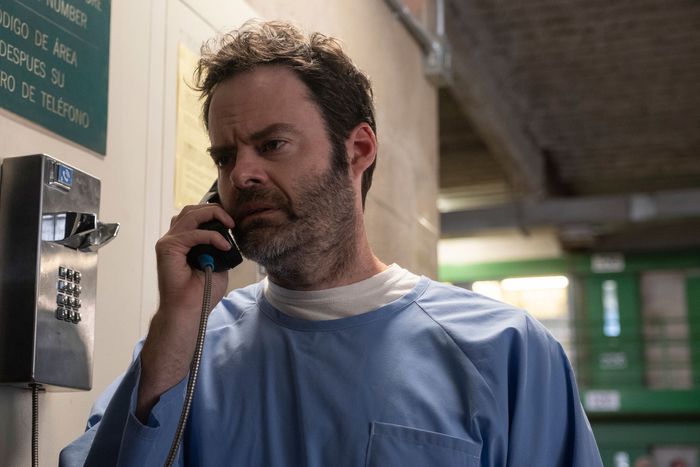

Sunday’s season-four premiere, “yikes,” picks up a couple hours after “starting now” left off, with Barry in custody and Sally flying home to Joplin, Missouri, for which she named her short-lived web series. The first few minutes of the episode confirm Barry is as vividly directed and deftly acted as ever: A graceful pan follows Barry as he walks to his jail cell with guards in the foreground listening in awe to a press conference about the “cop killer” now in their midst. Moments later, an extreme close-up of a man’s dirty fingers curling over the airplane-seat headrest in front of Sally offers a nightmarish reminder of her explosive rage against the biker-gang home intruder at the end of season three. Elsewhere throughout season four (seven of eight episodes were provided for review), Hader’s confidence behind the camera makes for creative combinations of visuals, voice-over dialogue, and beautifully rendered scenes of grisly violence. Goldberg is riveting as she careens between new identities for Sally, from estranged daughter to resentful acting coach; Winkler expertly guides his character to new heights of conceit; and Wisdom is a cool presence whose menace is utterly convincing, in particular when paired with the dry bemusement of new cast member Patrick Fischler. The rare humor Barry still offers comes from Chechen mobster NoHo Hank (Anthony Carrigan). Hank’s outlandish outfits and zealous cheeriness provide a couple of wry grins. Laughs, though? Elongated moments of levity to puncture our immersion in this stew of narcissism and despair? Not so much, aside from one wonderfully unexpected cameo that leads to a lovely bit of banter regarding Hank’s podcast preferences.

The uniform consistency of these performances doesn’t quite match the season’s writing; there is a convolutedness to how Barry arranges these characters for a shared season-long arc, and a certain twist is somehow both bold and anticlimactic at the same time. But the penultimate episode, “a nice meal,” is so clever in how it strips Barry, Gene, Sally, and Fuches to their core pernicious impulses that it makes the early meandering worthwhile. By wondering whether religion, fame, parenthood, or wealth can turn us into the version of ourselves that we want to be, Barry returns to its foundational question about reinvention and performance: Is there more value in being authentically artificial or artificially authentic? Over and over this season, Hader fills the frame with a specific image of Barry: his back to the camera, his shoulders slumped, his barely glimpsed profile set in a morose mask — a man weighed down, emotionally and physically, by his own choices. Describing any of this as a “comedy,” dark or not, might be Barry’s funniest final joke.

Barry’s eight-episode fourth season premieres on HBO on April 16.