Batman cartoons rarely feel locked into a specific era of Batman’s comic-book life — or the character’s history in general. The Batman took place in an anime-inspired millennial techno dream where even the Penguin was a fierce martial artist, and The Brave and the Bold took glee at bouncing across Batman’s wide mythology. Even the famed Batman: The Animated Series picked favorable spots from Batman’s legend to meld into quality TV.

But the upcoming Prime show Batman: Caped Crusader, at the behest of Bruce Timm (who co-created BTAS) and his collaborators, opted to stick Batman firmly in the setting of his origin — a post-Depression period where the noirish mood ran thick and the villains lacked many of the whimsical flourishes that they’d be saddled with in the decades to come. It’s a time when Batman is just starting out, and he’s so bitterly consumed by his obsession that the line where he ends and where Bruce Wayne begins is nearly nonexistent.

But while prior cartoons have mixed and matched Batman scenarios, the comics, ranging from the actual early years to modern dives into the Dark Knight’s past, have been eager to make their claim on how Batman began. So, if you’re trying to get into the mood of what is sure to be one of 2024’s biggest animation events, or if you’re curious about how Batman’s early tales have evolved in the past eight-plus decades, read these 12 comic-book stories.

Note: To make the specific issues easier to find in the massive backlog of DC Comics, the cover dates have been listed rather than the actual publication dates.

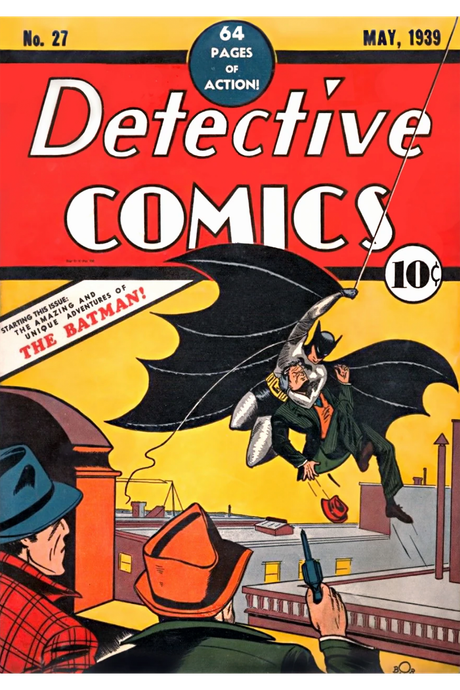

Detective Comics #27 — May 1939

The first appearance of Batman (or, as he’s referred to here, “The Bat-Man”) is one of the most fabled comic books in history. Its influence on Caped Crusader is evident from the onset, especially when it comes to the look of Batman, with his shroudlike cape and elongated ears. But this Batman is also famous for his ferocity, which, in retrospect, is mostly a case of creators Bill Finger and Bob Kane still working through exactly what they want the character to be. Later incarnations of Batman would seek to prevent the demise of his foes, lest the act of murder turn Batman into the very villain he’s fighting against. This Batman dumps a corrupt businessman into a vat of acid and coldly remarks, “A fitting end for his kind.”

Reading the full issue of Detective Comics #27 might be surprising for new comic readers — Batman’s “The Case of the Chemical Syndicate” is just part of an anthology of stories. The heroes from the other stories, like “Speed” Saunders and Bart Regan, have mostly been lost to time. This wasn’t an outlier; even Spider-Man had to share his 1962 Amazing Fantasy debut with a gaggle of forgettable weirdos. But it shows that, despite his bare-bones inauguration, something about The Bat-Man stood out. And eventually, the Detective Comics line would become entirely devoted to his adventures.

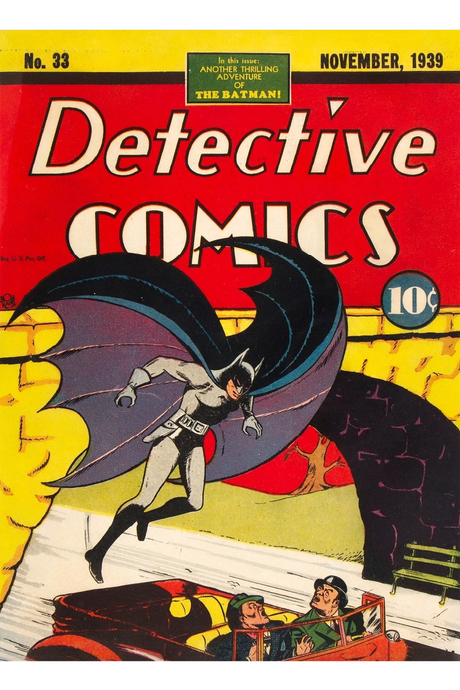

Detective Comics #33 — November 1939

“Bare bones” might sound like an exaggeration for Batman. He didn’t have to go through a transformation like Superman, who would spend his first few years in a superhero metamorphosis of gaining powers. But so many of the attributes that we consider key features of Batman didn’t show up until later. His stalwart butler Alfred wasn’t around until Batman #16, and he didn’t have a real “Batcave” until the 1943 movie serial. It would also take months after his debut for readers to find out Batman’s origin story.

Detective Comics #33 does so in the span of two pages (a quarter of which is devoted to just a big picture of Batman looking glumly at his own tragic beginnings). “The Legend of the Batman — Who He Is and How He Came to Be!” is rather beautiful in its lack of complication. Batman, after physically training and becoming a “master scientist,” figures that the crooks he’ll be tackling are a “superstitious, cowardly lot,” and that to strike fear, he’ll need to be a “terrible … creature of the night.” It is after these pages that we find the Batman of Caped Crusader, obsessively driven and single-minded in his mission.

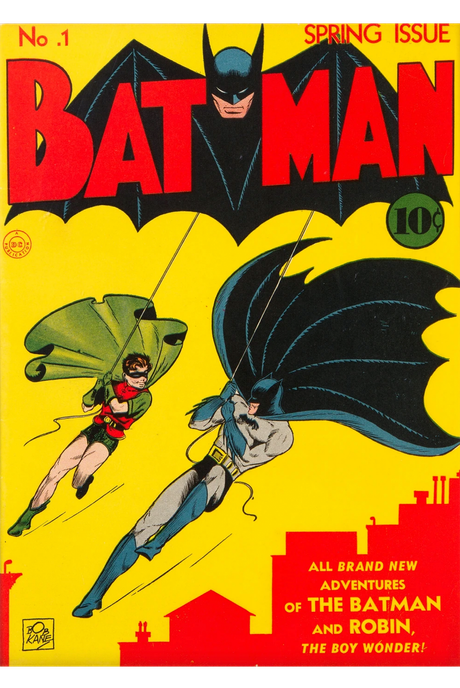

Batman #1 — Spring 1940

When Batman got a comic book solely devoted to him, he had already been joined by Robin (The Boy Wonder had shown up in Detective Comics #38), a character that would come to represent the humanity and escapism in Batman’s crusade. But it wasn’t devoid of the criminal macabre and science-fiction-infused madness that Batman had accrued, either. Batman #1 not only features the arrival (and momentary death) of the Joker but the first appearance of Catwoman and the return of Hugo Strange, the mad doctor who’s now resorted to experimenting on asylum patients and turning them into hulking monsters.

A frequent misconception of Batman is that his early stories are bereft of the fantastical. This is mainly because we tend to associate the fantasy elements with the more lighthearted stories to come. But as this comic and Caped Crusader show us, Batman has always dabbled in nightmares and flights of pure imagination. Instead of working against his noirish trappings, he instead filters them through it. Impossible horrors, like the ghoulish Joker surviving a brutal, self-inflicted stabbing or Strange’s medical abominations, coincide with the relatively grounded underbelly of Gotham City. And so the best Batman stories often come not from rearranging and deleting pieces until he “works,” but rather in distilling various, seemingly disparate elements.

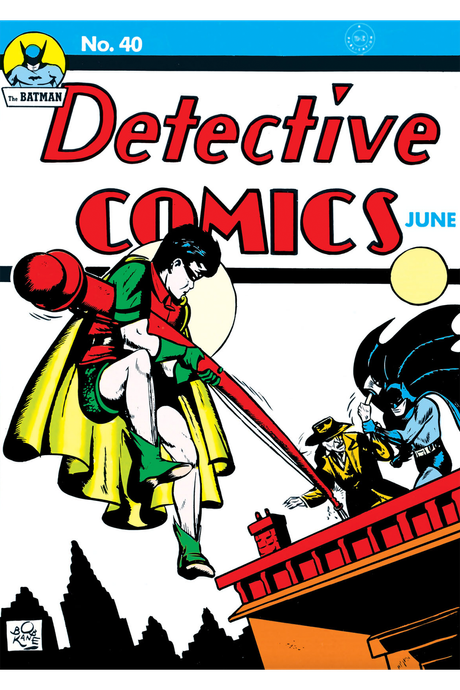

Detective Comics #40 — June 1940

Taking place very early in Batman’s career, Caped Crusader presents takes on supervillains that are distinctly golden age. Notably, it will feature Clayface, a character who in modern times is known for his shape-shifting feats. Batman: The Animated Series, by far the most famous and well-regarded of Batman’s cartoon efforts, showcased him in all of his gooey glory. But Clayface (or Clayfaces, as there have been a few) wasn’t always a pile of mud. His original version was Basil Karlo (named after Frankenstein actor Boris Karloff), a horror-movie performer who operated under the scary guise of his former character.

Caped Crusader pays homage to this creepy appearance, fitting him into a collection of foes that straddle the line between colorful costumes and psychopathy. Similarly, the Catwoman design also takes its cues from the splashy 1940s, which was a go-to comic-book look for Catwoman until skintight leather became the norm for the burglar/romantic interest. Again, Batman’s early years aren’t one unified entity. Rather, they’re a growing amalgamation of things that provide a rich resource for an adaptation.

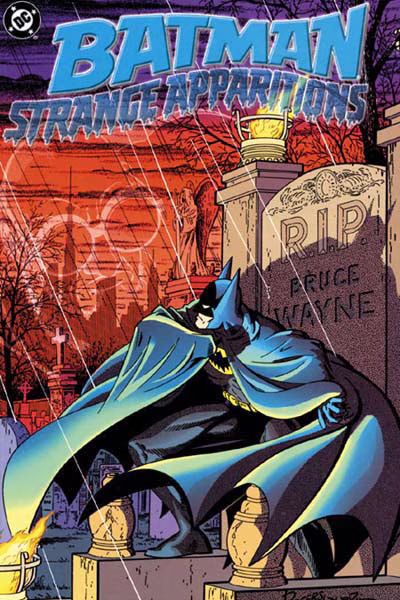

Batman: Strange Apparitions — May 1977 to October 1978

When the 1960s Batman series starring Adam West ended, the character went through a much-needed comic-book overhaul. Many of the campier aspects that had defined the previous two decades were dropped, but Batman returning to his “roots” was a gigantic process. His mythology was far bigger than it was in 1939, so it can be hard to know where to start if you want to dive into Batman’s “new beginning.” For a sort of greatest-hits collection of the era, look no further than the Strange Apparitions collection.

By assembling Detective Comics #469-479, Strange Apparitions blends a return to Batman’s gritty urban genesis with a revitalization of some of his most famous (and previously exhausted) foes. It also tries to dive into Batman’s psychology in a way that was utterly missing in decades past, and it never lets us forget the tortured man behind the mass merchandised mask. The 1970s was big on this. How is Batman both a haunted avenger and a centerpiece of superhero derring-do? It’s a question that also plagues Caped Crusader, where Batman is an exciting crime fighter and a grim, damaged orphan. Every adaptation of Batman has an answer for this balance, and Strange Apparitions provides one of the most memorable ones.

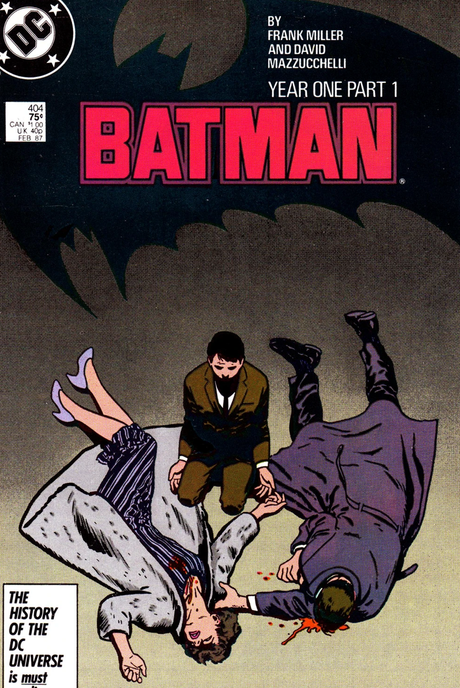

Batman: Year One — February to May 1987

Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns was widely praised for aging the Dark Knight and showing readers a Batman that had tried to escape his own obsession, only to be inevitably pulled back into his sacred war. So it was fitting that Miller would then pen Batman’s beginnings, and he did so with the almost-as-famous-but-not-quite Batman: Year One. In it, we find a Gotham City that’s pretty much given itself up to be swallowed alive by corruption. The dual arrival of Batman and Captain James Gordon (who also stars in Caped Crusader as a beleaguered champion of hope in a failing system) proves there is some good to be found amid the moral detritus, however complicated it may be.

This focus on Gordon, an integral supporting character in the DC universe, does a lot for him. Mainly, it establishes that Gordon is a fascinating character in his own right, even without his growing connection to Batman. He’s anxious, strong-willed, and capable of personal failures — a fleshed-out role that could have easily been realized as Batman’s little mustached cop buddy. Overall, Batman: Year One ends up doing more for Gotham’s less-costumed citizens than it does for the guy in the title, establishing and filling out his world for future adventures.

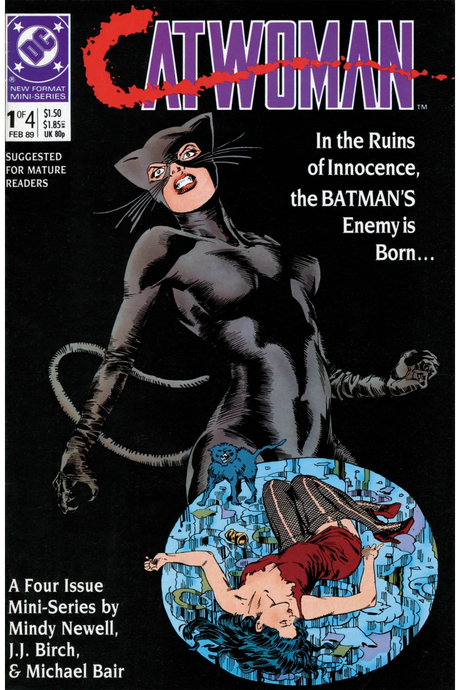

Catwoman: Her Sister’s Keeper — February to May 1989

Batman: Year One also reintroduced Catwoman’s alter ego, Selina Kyle, into Batman’s world, taking on a young Bruce Wayne in a pre-costumed (and what now seems like a predestined) fight. The biggest problem is that Sin City creator Frank Miller also made her a dominatrix/prostitute, which wouldn’t necessarily be an issue until you remember that Miller’s ability to empathetically write female characters in general is … uneven. Catwoman: Her Sister’s Keeper tries to do for Catwoman what Year One did for Batman, but luckily Mindy Newell is the writer on this one. She manages to keep Catwoman’s origin as hard-boiled as Batman’s while also making her a more dynamic character.

Catwoman has always been one of Batman’s A-list rogues, but the late ’80s and early ’90s put her into overdrive. Comics like this, her movie role in Batman Returns, and her heavy inclusion in Batman: The Animated Series gave her a standing that was only second to the Joker. Caped Crusader places her at the forefront as well, as she presents not just an interesting villain but a chance for the deeply reserved Batman to experience the very human feeling of longing. Catwoman does the same at the end of Her Sister’s Keeper, planting a kiss on his lips and leaving him wondering about her (and his own emotions) for years to come.

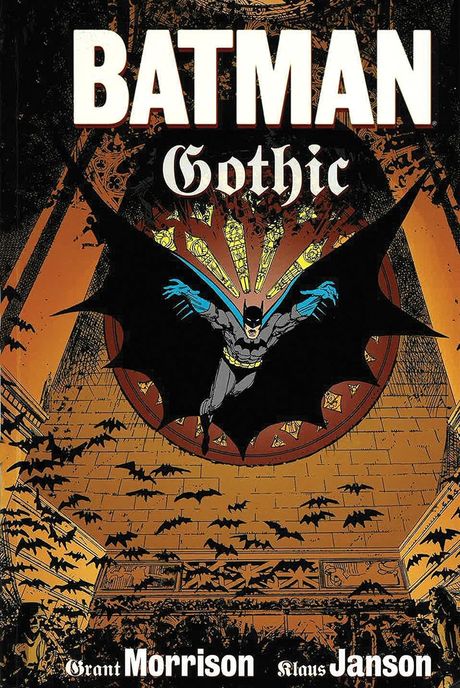

Batman: Gothic — April to August 1990

In the wake of the megasuccess of the 1989 Batman film, another comic title was launched into stores: Legends of the Dark Knight. It was free of the pressing continuity issues that would envelop the other series. Thus, Legends allowed writers to tackle stories from Batman’s past, with a major one being Batman: Gothic. Written by comic-book wunderkind Grant Morrison, it’s a wonderful look into the domino effect Batman had on Gotham City after Year One. Now a playground for all manner of man and monster, the Gotham mob seeks out Batman’s help to stop a serial killer.

Set pretty firmly in a post–Year One world, Gothic is filled with the noir creepiness and bizarre turns of fantasy that permeated early Batman comics. And while Morrison would eventually pen a fantastic run with Batman that delighted in the many intricacies, otherworldly or otherwise, of his mythology, Gothic is stripped down to an emotional rawness. Like Caped Crusader, it captures a Batman that is new and lonely, facing a foe that counters him personally and scrapes at a wound that’s still bleeding.

Batman: Prey — September 1990 to February 1991

One key villain that the Caped Crusader team has focused on is Harley Quinn, a character that began her existence as the Joker’s former psychiatrist/current wacky gun moll and evolved into a franchise superstar. She’s had her personality flip-flopped for Crusader. As Bruce Wayne’s psychiatrist, she’s affable and kind, but when the costume goes on, she becomes a monster to match anything that her former clown boyfriend has accomplished. It’s an exciting turn, one that recalls the renewal of longtime Batman foe Hugo Strange in Batman: Prey.

Another Legends of the Dark Knight story line (this comic was good), Prey homed in on Strange’s particular ability for menace. As a demented psychiatrist with a keen interest in the inner workings (and dismantling) of the human mind, Strange attacks Batman at his core. It also helped push an idea that would become commonplace now: Each of Batman’s foes has a kind of psychological relationship to Batman, and each represents a piece of Batman’s own traumatized mind. And as we’ll see in the next recommendation, this extends beyond the household names.

Batman: Blades — June to July 1992

Batman: Caped Crusader doesn’t just dabble in reinventing Batman’s A- and B-list foes (though the show does include Harley Quinn, Clayface, Catwoman, Two-Face, and even the Penguin). It also runs down the list into guys like Onomatopoeia, Gentleman Ghost, and Firebug, characters that are easy to forget in DC Comics’ sprawling pantheon. It’s reminiscent of Batman: Blades, another Legends of the Dark Knight installment that saw Batman taking on Cavalier, a swashbuckling foe with his own brand of moral gallantry.

While someone like Cavalier might seem impenetrably locked in his 1940s debut, Blades is a crash course in taking a seemingly dated character and proving that they’re more than relevant in a new (old) age. He’s gone from being a weirdo in a Musketeer outfit to a disillusioned wannabe hero who, like Batman, must confront his own internal battles and face the risk of spiraling out of control. Of course, because it’s an adventure comic, Batman gets to have a sword fight with him as well (Batman sword-fights a surprising foe in the Caped Crusader series, too. Of course, it’s common knowledge that if you have the chance to stick a sword in the hands of a bat-themed ninja, you take that chance.)

Batman: The Long Halloween/Dark Victory — December 1996 to December 1997 & December 1999 to December 2000

The world of Caped Crusader has many narrative threads, ranging from Batman’s life, to the trials faced by the Gotham City Police Department, to the evolution of his ridiculous foes and the mobster-laden streets that they pour into. It’s much more than a revolving-door system of crimes and crooks. Rather, it’s an ecosystem where courses meet and diverge. For example, Two-Face typically begins his story as the campaigning, Batman-befriending, gangster-wrangling district attorney Harvey Dent, and then crosses over into the realm of chaotic villainy when he becomes Two-Face (providing another visual metaphor to Batman’s own theme of duality).

The Long Halloween and Dark Victory tell Two-Face’s story in a way that makes him seem like a support beam for Gotham’s entire infrastructure. It’s probably the most devoted origin tale a Batman character has ever gotten, and it makes it clear that one thing can’t happen in a part of Batman’s world without it having a ripple effect across everything else. Featuring a menagerie of Batman’s antagonists and side characters (Dark Victory even finds room to give Robin an effective new debut in Batman’s chronicle), it’s not just a great starting point for fans new to his comics, but a powerful depiction of how tragic change doesn’t leave anyone unscathed.

Batman: The Man Who Laughs — April 2005

There have been many attempts to adapt early Batman comics; even Caped Crusader tries to funnel its 1940s trappings for a 2024 audience. But few have been as successful as Batman: The Man Who Laughs. Written by Ed Brubaker (who is also the head writer on Caped Crusader), it essentially retells the Joker story from Batman #1 and dumps many of the flourishes that have been added to the Joker since. He’s cruel, methodical, and ghastly, a noirish nightmare clad in a corpselike grin.

It’s a short comic, but it thrives on tapping into the whodunit potential of Batman’s detective work and the stunning force that is the Joker, a character no one is quite prepared for. It serves as a sequel to Year One (the Joker is teased at the end of that comic, a reference that moviegoers see replicated at the end of Batman Begins) and also as an omen for Batman’s future. As we’ve seen, Batman’s origin wasn’t just an endless line of thugs and ne’er-do-well industrialists. It didn’t take long for the freaks to come stomping through. Batman: Caped Crusader won’t have an easy task in trying to balance superheroism with early-’40s crime drama and pulpy, outsized horror, but if it pulls it off, it might be the first animated series to properly capture a time in Batman’s life that the comic books have aspired to illustrating for 85 years.