This story originally ran in 2018 and is being republished for Halloween.

For nearly as long as there have been movies, there have been horror movies. The genre was there from the start, luring in audiences who wanted to witness things they’d never thought they wanted to witness before. Vampiric monsters, ghastly apparitions, human abnormalities — they were all the stuff of nightmares a century ago, just as they are today.

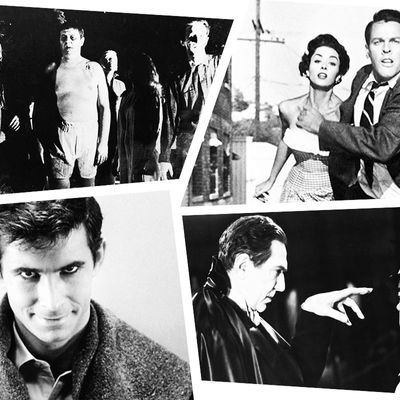

Many of the titles on this list of great black-and-white horror movie are well-known classics, others are smaller cult favorites, and a couple are recent works from directors who appreciate the potential power of black-and-white cinema. But they’re all worth revisiting this Halloween season.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Widely considered the earliest example of horror cinema and the quintessential piece of German expressionism, Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a stylized nightmare of sharp angles, abstract locations, diagonal staircases, and violent landscapes. The stark contrasts between the black-and-white colors are jarring to the eye, and add a layered intensity to the psychological delusions experienced by the audience. Perceptions of the world around are mangled by the visual stimuli, resulting in a horrific film that successfully captured the fear and mistrust of the isolated post–World War I culture that created it.

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922)

Released at the height of German expressionist cinema, Nosferatu was an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and was almost lost forever after Stoker’s heirs sued over the adaptation and a court ruling ordered that all copies of the film be destroyed. Fortunately, a few copies of the film survived. Director F.W. Murnau was an innovator, combining built sets with real locations and adding a new layer of realism to the vampire tale, as well as trick photography to present Count Orlok as truly otherworldly. It’s an infamous work of art, and its messages about political unrest and illness epidemics serve as the beginning of horror as social commentary.

The Man Who Laughs (1928)

By definition, Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs is not a horror movie, but a romantic drama not unlike The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Still, as a major influence on the later Universal Monster movies and the inspiration for the DC Comics’ illustrations of the Joker in the Batman comics, The Man Who Laughs’ legacy far surpasses its initial introduction as a German romance film. Largely due the startling features of the titular character (not to mention the looming gloom that surrounds him), the film’s imagery leaves the viewers with a deep level of dread.

Universal Classic Monsters (1931–1954)

Among the most iconic of all black-and-white horror films, the talkies of Universal Monster Movies (Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolf Man, The Mummy, The Invisible Man, Creature From the Black Lagoon, and Bride of Frankenstein) all established the building blocks for what would shape the modern horror film. Creatures were used as a vehicle to tell stories about xenophobia, sexuality, challenging God, questioning one’s identity, the inherent violence of mankind, and the fear of the unknown. Even in monochromatic tones, the Universal Classic Monsters painted worlds of horror, eliciting horror through trailblazing cinematic techniques rather than relying on the splatter or gore that would define the genre in later years.

Freaks (1932)

Banned in Britain until the 1950s and easily one of the genre’s most controversial and ethically questionable films, Tod Browning’s Freaks serves as an examination of the monstrous extremes of human nature, forcing audiences to question their preconceived perceptions of those that appear different than the “norm.” Browning was fresh off of the success of Dracula when he made Freaks. The final moment of the film remains one of the most shocking endings in pre-code horror history, and takes a stance now common in horror: that sometimes the worst monsters are those that walk among us, undetected.

Murders in the Zoo (1933)

As one of the first examples of an “animals run amok” horror film, Murders in the Zoo was extremely graphic for its time, and remains to be a rather distressing film by even today’s standards, due in large part to the footage showing the depressing state of zoos in the 1930s. Animals are crying out for food and kept in iron-clad cages, and at one point, they legitimately fight one another. In the film, a maniacal zoologist grows increasingly jealous of his unfaithful wife and decides to utilize live animals as a weapon to achieve “the perfect murder.” Barely over an hour long, the film unsuccessfully tries to marry horror and comedy together, but does provide one of the most jarring opening sequences of a film from this era using a man’s mouth, a needle, and some thread.

Cat People (1942)

One of the first true low-budget horror success stories was also the saving grace of the financially failing RKO Studios. Perhaps the film’s greatest contribution is the iconic “bus scene,” a moment filled with such intensity that it serves as the premiere example of what would later become known as “jump scares.” It continues to serve as one of the most effective scares in horror history. Billed with a no-name cast and serving as the start of horror-producer extraordinaire Val Lewton’s career, Cat People was a revolutionary landmark in horror cinema.

The Seventh Victim (1943)

Satanism and lesbianism go hand in hand in another Val Lewton–produced masterpiece. Part noir, part horror film, The Seventh Victim is one of the first movies to treat women in horror as fully fledged people with their own thoughts and desires, allowing them full agency. The women are strong-willed, mouthy, and uncharacteristically bold in this pulp staple. Ultimately, it’s suggested that the power of these women comes from their participating in a Satanic cult, but since the film renders male participation to be all but useless, it deserves a rewatch by contemporary eyes.

The Uninvited (1944)

What is perhaps one of the first haunted-house films to treat ghosts as legitimate threats and sources of horror, the British-made flick has largely gone unnoticed by American audiences. That’s a crime: It’s one of the titles that Guillermo del Toro cites as having a major impact on his own filmography. The Uninvited boasts high-caliber acting performances and, crucially, practical in-camera ghost effects that rely on lighting, sound, and wind machines. It’s moody, it’s creepy, and while it may not deliver the scares today like it did then, a rewatch showcases an influence that can still be felt.

Dead of Night (1945)

Before horror anthologies became a subgenre of its own, there was Ealing Studios’ Dead of Night. Connecting five different stories from British filmmakers and a wrap-around, the film is a psychological creepfest and delivers what is arguably the best work of director Charles Crichton. In the film’s climactic ending, we’re introduced to a story involving a ventriloquist dummy that set the stage for just about every inanimate-object-that’s-actually-alive film moving forward. Even today, the cold, dead eyes of the sinister dummy serve as nightmare fuel.

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945)

I’m possibly cheating to include this film on the list, but The Picture of Dorian Gray is one of the first to showcase black-and-white as an aesthetic choice rather than a filmmaking necessity; four-color inserts of three-strip Technicolor were used for Dorian’s portrait, utilized as a special effect in a black-and-white world. Having that isolated moment of Technicolor heightens the horror of seeing Dorian’s painting age while he himself remains youthful. The film is a triumph in deep-focus cinematography, and earned Angela Lansbury her second Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress (not to mention her first Golden Globe win in the same category).

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948)

As interest and popularity in horror movies began to wane, studios struggled to breathe new life into what had been one of their most profitable sectors. Enter the horror-comedy. While plenty of old movies attempted to add levity to horror, Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein set the standard for horror-comedies and left an impact that’s still emulated decades later. By adding Bud Abbott and Lou Costello to pal around with established monsters like Lon Chaney Jr. and Bela Lugosi, Universal struck gold and spawned a franchise.

Them! (1954)

One of the first of the 1950s “nuclear monster” films, and the first “big bug” feature, Them! was a monumental success for Warner Bros. pictures, and one of the best examples of what would become the science-fiction subgenre. Borrowing elements of horror as well as influence from the Japanese kaiju flicks, Them! is one of the earliest examples of genre fusion under the horror umbrella. The film avoids the tropes that would become popularized in later B-movie cinema, opting instead to treat the gigantic ant monsters as legitimate threats and presenting the horror as sincere.

Night of the Hunter (1955)

The unfortunate truth of Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter is that this is easily one of the best horror thrillers ever made, and easily one of the most forgotten. It’s the sole directorial effort of Laughton and stars Robert Mitchum, a prominent anti-hero of the noir movement who often played second banana. However, The Night of the Hunter is compelling, visually stimulating, and downright thrilling. It’s a film that feels so far ahead of its time that it would play better for today’s audiences than it surely did during the mid-50s.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

Although not the best rendition of the Body Snatchers story, the original 1956 incarnation is one of the best examples of a sci-fi–horror film rooted in reality, preying on the human fear that we are far more vulnerable to destruction than we’d like to believe. Released at the peak of Cold War and Red Scare paranoia, the political roots of Body Snatchers were far less ambiguous than the films that came before it, and the film successfully solidified the relationship between politics and horror.

The House on Haunted Hill (1959)

William Castle’s magnum opus, The House on Haunted Hill is one of the greatest haunted-house movies of all time. An eccentric millionaire played with perfection by Vincent Price offers $10,000 to anyone who can spend a night in the titular mansion, the site of a plethora of murders. The participants are faced by a ceiling dripping blood, a severed head, a vat of acid in the cellar, and the iconic skeletal apparitions that walk on their own. While a fantastic movie in its own right, The House on Haunted Hill’s more prominent legacy is rooted in Castle deciding to gear his horror films to a teenage market, a trend that horror films followed moving forward.

Eyes Without a Face (1960)

Georges Franju’s ghastly yet dreamlike examination of the quest for physical perfection, the social value placed on women’s appearances, and guilt. Once a respected surgeon, Dr. Genessier now lives in isolation, experimenting on animals and helpless women lured to him by his faithful nurse and lover Louise. The film is startlingly graphic and drips with art-house elements that greatly influenced filmmakers that followed. Eyes Without a Face is presented in stark black-and-white, but the surreal visual imagery added a muted softness to the chaotic horror within.

Black Sunday (1960)

Master of horror Mario Bava began his career with Black Sunday, an Italian gothic masterpiece and easily his most celebrated work. With sex appeal, Bava builds a horrific landscape enhanced with slick camera work and intense black-and-white contrasts. The film plays around with both vampire and witch mythology, which eventually leads to a spiked mask being hammered into a woman’s face. The visual of Barbara Steele’s pale skin covered in deep, black holes has become an iconic image from classic horror, perfectly exemplifying her role as both attractive and horrific, desirable and revolting.

Psycho (1960)

Yes, it’s most influential horror film of all time. But it bears repeating: Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho was a true game-changer in horror cinema. The sight and sound of Marion Crane meeting her demise is synonymous with what one imagines when hearing the words “horror movie.” Psycho gave roots to the slasher films that were to come, not to mention completely disrupted the idyllic world of the 1950s. The quick-cutting editing technique paired with one of the greatest scores ever crafted and Norman Bates’s mania have solidified Psycho’s place in not just the horror canon, but the canon of all-time cinematic greats.

The Innocents (1961)

Based on Henry James’s 1898 horror novella The Turn of the Screw, this remarkably unsettling psychological horror film from Jack Clayton continues to serves as one of the premiere British horror films. It’s also one of the earliest and best examples of the “creepy children” subgenre. The plot is on the heavy side: The Innocents plays with the mental anguish of a person desperately trying to make sense of the world around them while simultaneously dealing with their own emotional turmoil. The film’s iconic ending scored an X-certificate upon the first release, and theorists continue to this day to analyze the subtext of sexual repression, ghastly possession, and how the two intertwine.

Carnival of Souls (1962)

Hailed by many as an independent masterpiece, Carnival of Souls plays more like an extended version of an episode of The Twilight Zone than it does a true-blue horror film. A low-budget endeavour with art-house sensibilities, the film’s fear factor is rooted in its odd visual imagery and dramatic light play. Director Herk Harvery also plays the horrifying apparition that haunts the leading lady’s imagination, a manifestation of her repressed fears as a malevolent force that she cannot escape, try as she might. Carnival of Souls is dark, atmospheric, experimental and a disturbing look into full-blown mental break.

Dementia 13 (1963)

B-movie master Roger Corman produced this Psycho knockoff, which is also the non-pornographic feature debut of director Francis Ford Coppola. With a noticeably rushed script that nonetheless provided moments of legitimate shock, Dementia 13 was almost universally panned by critics and audience members alike. However, the movie is an extremely important addition to the black-and-white horror canon if for nothing else its unashamed aping of Hitchcock’s masterpiece. From this moment forward, horror began to unapologetically borrow from films that came before — an early sign of the remake culture to come.

Strait-Jacket (1964)

While Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? launched the “hagsploitation” subgenre, it was Joan Crawford’s starring role in William Castle’s Strait-Jacket that perfected it. Some critics viewed the film as one of the worst ever made, but Castle’s theatrical gimmicks developed the film into an audience favorite, and Crawford’s turn as a psycho-biddy set the bar for so-called “washed up” actors retreating to horror films once their Oscar-bait roles had run their course.

Repulsion (1965)

Despite being over 50 years old, Roman Polanski’s Repulsion remains one of the most disturbing films ever crafted. The first of his “Apartment Trilogy,” Repulsion is a psychological torture chamber of hallucinatory exploration. What begins as a calm and somewhat slow dissection of a characterless woman, quickly turns into a complete mental unraveling, a masterpiece in capturing the nightmare chamber that is an unwell woman with unchecked emotional traumas.

Hour of the Wolf (1968)

The sole horror entry in Ingmar Bergman’s filmography, Hour of the Wolf is a psychological journey into the realm of perhaps the scariest world of all: the deep recesses of a human’s personal demons and existential turmoil. Every minute of this film is drenched in ominous dread, frequently crossing into the supernatural. Viewers are ambushed by jarring visuals and ambitious moments of cinematography (there’s a dinner scene that is downright remarkable), proving that what many believe is one of Bergman’s lesser works is, perhaps, one of his most interesting.

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

George A. Romero is king of the zombies and the father of contemporary horror cinema, full stop. This low-budget, independent film from Pittsburgh completely revolutionized the horror genre and created a monster that has reigned supreme for the last 50 years. Before Romero, horror films were often set in faraway lands of isolation, but he brought horror to the suburbs, where families were only a monster outbreak away from meeting their demise. While he claimed until death that the casting of Duane Jones, an African-American as the lead role, was purely based on his acting talent, Romero’s decision to present a black protagonist is still one of the most radical moves in horror history.

Eraserhead (1977)

The debut of auteur David Lynch, Eraserhead is a surrealist and tantalizing slice of cinematic horror that combines excessive gore, eroticsm, brilliant black-and-white cinematography, melodramatic performances, excessively dark humor, and a healthy dose of gore. It’s truly unlike anything that came before it, and nothing has come close to matching its power since — the reveal of “the child” is one of the most traumatic visual scenes ever recorded in black-and-white.

A Field in England (2013)

There are few directors working today with as distinctive or as impressive of a reputation as Ben Wheatley. Covering a wide spectrum of genres across his career, his horrific period piece set during the English Civil War is perhaps his greatest cinematic endeavor. It examines the psychological breakdown of men completely destroyed by war under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs. Written by Wheatley’s wife, Amy Jump, the dialogue serves as one of the strongest elements of the film, nestled with visually striking scenes of cosmic horror.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014)

Ana Lily Amirpour’s feature debut is an Iranian-American vampire-Western rife with rage-filled feminism. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is as beautiful as it is peculiar, and as fascinating as it is haunting. Her strength is in creating atmosphere, a change of pace for a monster genre that frequently thrives on high-octane thrills. The film feels like an erotic ’80s album cover come to life, and managed to breathe new life into one of horror’s oldest subgenres (see: the second film mentioned on this list).

The Eyes of My Mother (2016)

Both breathtakingly stunning and one of the most legitimately fucked-up films in recent memory — a feat made all the more impressive by the fact that it’s Nicolas Pesce’s debut feature. The film moves at a deliberate pace, slowly creeping under the skin of the viewers, and staying there long after the credits roll. The black-and-white cinematography only adds to its otherworldly aesthetic. The Eyes of My Mother is presented as an art film, but don’t be fooled: It’s a truly grotesque and emotionally jarring slice of cinema.