Denis Villeneuve might be one of the less likely directors to find himself helming massive Hollywood blockbusters. Consider this: Villeneuve released his first film in 1998 and his second in 2000, then essentially took a yearslong break to hit the reset button and, he recently told The Hollywood Reporter, learn how to “approach cinema differently.” That involved observing theater directors at work and learning how better to communicate with actors. He resurfaced in 2008 with Next Floor, a nearly wordless satirical short film in which a gathering of formally dressed elites gorge on a feast of increasingly vile dishes. This isn’t the sort of career path that always proceeds to directing the biggest films imaginable.

Yet that’s precisely where Villeneuve finds himself after completing a two-part adaptation of Frank Herbert’s science-fiction landmark Dune, a project once widely deemed unadaptable after David Lynch’s attempt in 1984. Yet Dune might as well have been custom-made for Villeneuve, who designed storyboards for an imagined adaptation with his best friend as a teen. To work, any adaptation of Herbert’s book has to capture the violence, moral ambiguity, and human drama of its far-future world without losing the spectacle or hallucinatory weirdness.

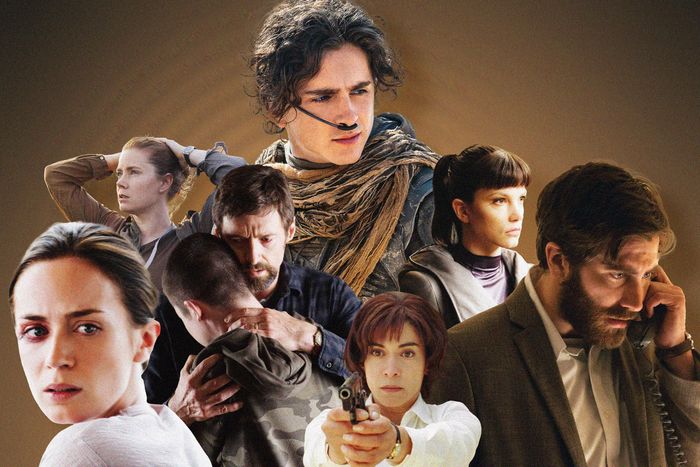

That intersection has become kind of a sweet spot for Villeneuve, even outside the science-fiction genre. Complex, conflicting emotions and the capriciousness of fate have played central roles from the beginning of his career. It’s just the stage that’s gotten larger.

11. August 32nd on Earth (1998) and 10. Maelström (2000) (tie)

Villeneuve’s first two features are so of a piece it’s hard to think of them separately. A car accident plays a central role in both, as does an ambiguous relationship between two people who may or may not belong together set along the thin line between life and death (though only one is narrated by the repeatedly beheaded corpse of a talking fish).

In August 32nd on Earth, Simone (Pascale Bussières), a model in Montreal, reexamines her choices after walking away from a car accident and, after asking the date, being told it’s August 32. To redirect her life, she decides to conceive a child with her best friend Philippe (Alexis Martin), who’s not-so-secretly in love with her. This, for some reason, involves flying to the Utah desert (a decision that results in one of the film’s funniest sight gags when the couple discovers the flat, barren spot they’ve chosen offers no obstructions to prying eyes). Villeneuve returned two years later with Maelström, in which Marie-Josée Croze plays Bibiane, a struggling Montreal businesswoman who falls in love with a Norwegian Canadian diver named Evian (Jean-Nicolas Verreault) after killing his father in a hit-and-run accident, a story memorably recounted by the aforementioned fish (voiced by Pierre Lebeau).

An interest in dark whimsy and moral ambiguity drives both films. Both earned acclaim, and Maelström fared quite well in Canada’s Genie Awards, picking up six trophies, including the Best Picture, Director, Screenplay, and Actress prizes. (The fish, however, earned nothing.) Even if they now look like the most uneven films of Villeneuve’s career, they’re both compelling, unpredictable films. It’s easy to see why, at the turn of the century, they seemed to announce an exciting, distinctive, quirky new voice in Quebecois filmmaking. It’s just as easy to see, given his subsequent work, why Villeneuve now talks of them as something of a false start.

9. Incendies (2010)

In addition to reconsidering his approach to film, Villeneuve spent the years after his first films working on screenplays for Polytechnique and Incendies, which he made one after the other. An adaptation (co-written with Valérie Beaugrand-Champagne) of Lebanese Canadian playwright Wajdi Mouawad’s 2003 play, the latter flits between the past and the present as it depicts a tragedy whose full scope doesn’t become apparent until all the pieces have been put together. In the present, Quebecois twins Jeanne (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin) and Simon (Maxim Gaudette) respond differently to the reading of their mother Nawan’s (Lubna Azabal) will, which includes sealed envelopes to the father they didn’t know was still alive and a brother they didn’t know existed. Simon wants nothing to do with it. Jeanne heads to the unnamed Middle Eastern country of her birth in an attempt to honor her mother’s final wishes. As her quest proceeds, and grows more confusing, the film depicts scenes from Nawan’s past and a life about which her children knew nothing.

The film earned Villeneuve rave reviews, another clutch of Genies, and an Academy Award nomination in the Best International Feature category. It also suggested much of what was to come. Shooting on location in Montreal and Jordan, Villeneuve lets the story play out against an expansive backdrop without sacrificing its intimacy. Incendies’ bloody moments arrive with shocking suddenness but also feel like the inevitable results of larger political forces and multigenerational cycles of violence, themes that would recur in Dune, Sicario, and, most immediately, the Hollywood debut that would follow a few years later.

8. Prisoners (2013)

Villeneuve made the leap from Canada to Hollywood with this uncompromising thriller starring Hugh Jackman, Viola Davis, Terrence Howard, and Maria Bello as, respectively, Keller, Nancy, Franklin, and Grace, the parents of two girls who disappear from their small Pennsylvania town on Thanksgiving. When Jackman’s character believes he’s found the culprit, a local misfit named Alex (Paul Dano), he takes matters into his own hands, holding Alex hostage and torturing him for the details of his crime. Jake Gyllenhaal co-stars as Loki, the detective working the case. Working from a screenplay by Aaron Guzikowski and collaborating, for the first of three films, with cinematographer Roger Deakins, Villeneuve leans into the story’s darkness, both literally and metaphorically. But despite the grimness surrounding Keller’s quest for revenge, the film remains rooted in the humanity of its deeply flawed characters as it explores how evil begets evil.

7. Dune: Part Two (2024)

With no plans to make a sequel if the first entry in Villeneuve’s adaptation underperformed, Dune might have been an orphaned half-adaptation. Fortunately, that didn’t happen, allowing Villeneuve to finish the story (though a rumored adaptation of Dune Messiah and some obvious dangling plot threads strongly hint there might be more to come). If the first Dune has a slight edge over its sequel, it’s only because there’s less to discover here than the first time around, but even that’s relatively speaking, given remarkable elements like a long monochrome sequence under a black sun and the breathtaking imagery of sandworms stretched across the horizon. Some of its greatest strengths have nothing to do with strange worlds and special effects. The way Zendaya plays Chani’s shifting emotions as Paul assumes what might be his fated role as a messiah destined to be responsible for countless deaths captures the story’s tragic underpinnings with little need for dialogue. Considered as one long movie, the two Dune installments combine to make a stunning addition to the canon of classic science-fiction films.

6. Sicario (2015)

It would have been easy for a director to simplify screenwriter Taylor Sheridan’s story of Mexican drug cartels and escalating violence along the U.S.-Mexico border into a simple clash between good and evil. Instead, Sicario plunges headlong into the moral murk, following Kate (Emily Blunt), an idealistic FBI agent, as she joins a Joint Task Force headed by Matt (Josh Brolin), a deceptively glib CIA agent, and including Alejandro (Benicio del Toro), a former Mexican prosecutor who subsequently pursued other interests. From the opening raid (an almost otherworldly scene set in an American suburb) to a firefight that erupts at a border crossing clogged with unsuspecting travelers to a tense final confrontation best left unspoiled, Villeneuve keeps the tension high, sometimes letting it boil over in breathtaking violent scenes. But, once again, it’s the human costs exacted by these conflicts that are his main concern. Pair this with Incendies, and you’ll find one rhyming element after another.

5. Enemy (2013)

Villeneuve’s Hollywood work has made his name synonymous with the fantastic, but, talking fish aside (see: No. 10), he didn’t part ways with our understanding of reality until his final (at least to date) Canadian film. An adaptation of José Saramago’s novel The Double scripted by Javier Gullón, the surreal film opens with a scene set in a secret club in which women impale tarantulas on high heels and only becomes stranger from there. Jake Gyllenhaal stars as Adam, a glum Toronto history professor whose life becomes unhinged when he spots his exact duplicate, Anthony Claire, playing a bellhop in a Canadian comedy. After Adam reaches out, his life and Anthony’s (and the lives of their partners, played by Mélanie Laurent and Sarah Gadon) start to overlap in uncomfortable ways in what becomes a power struggle. Shot before Prisoners but released after, Enemy finds Villeneuve already playing with the conventions of genre filmmaking as he invests even seemingly mundane moments with a sense of dread. What it’s all about remains up for discussion, seemingly by design. It’s filled with references to history repeating itself and interest in the ways performative masculinity poisons its characters’ relationships with women, and leads to an unforgettable final image. But Villeneuve feels no obligation to settle on a single theme or reveal Enemy’s secrets. It’s opaque and inconclusive and all the more haunting for it.

4. Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

In some respects, that makes it a companion piece to Blade Runner 2049. Villeneuve’s follow-up to Blade Runner largely throws out the detective-story framework of the original to explore the wider universe suggested by Ridley Scott’s 1982 science-fiction classic. The film follows K (Ryan Gosling), a replicant blade runner who makes a discovery that leads him on a journey that will find him questioning the relationship between humanity and its android creations — and, by extension, the nature of existence itself. Less a sequel than a companion piece (though Harrison Ford does make a return as the original’s hero, Rick Deckard), the film isn’t short on action set pieces but allows plenty of room for philosophical pondering in the spaces between them. Another Deakins collaboration, Blade Runner 2049 also offers one stunning image after another — none more memorable than a ruined Las Vegas, though some come close. It’s the sort of film where it’s sometimes hard to believe what you’re seeing, making it all the more remarkable in an era in which corner-cutting effects have made images of the extraordinary seem pretty dull.

3. Dune (2021)

In the wake of Dune’s success, it’s worth remembering how easily it might have failed. Herbert’s novel is rich in lore and thick with characters with names like Glossu Rabban, Thufir Hawat, and Duncan Idaho. (Okay, that last one’s not that difficult.) Its story spans the galaxy and features numerous subplots, twists, and conspiracies. And it largely takes place in the desert. That’s a lot of hurdles to clear, but Villeneuve almost makes it look easy via the film’s imaginative designs, graceful effects, and clear (almost breezy) storytelling. Dune features visually stunning worlds that look lived-in, the sort of worlds where people move around in and die in rather than airless effects creations in which the human cast has been cut and pasted. They also serve as sites for some of the intense action sequences that Sicario revealed as one of Villeneuve’s skills, particularly a nighttime raid on the Arrakeen Palace that fills the sky with flames. But, above all, it’s the film’s investment in its characters — particularly could-be messiah Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet), his mother Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), and (more so in Part Two than this film), his Fremen mentor–lover Chani (Zendaya) — that keeps it grounded. It’s a galactic epic made at human scale.

2. Polytechnique (2009)

This, like Dune, might have gone horribly awry, but for much different reasons. Villeneuve returned to feature films after nearly a decade away with a dramatization of the École Polytechnique massacre, a 1989 incident in which a man driven by misogynist motivations and armed with an assault rifle killed 14 women and injured 14 of their fellow students at a Montreal university. Shot in stark black-and-white with a sense of on-the-ground immediacy, Polytechnique largely follows two students present at the massacre, both aspiring engineers: Valérie (Karine Vanasse) and Jean-Francois (Sébastien Huberdeau). Short (just 77 minutes, with credits), shocking, and unforgettable, it’s unsparing in its depiction of the horrific event but never feels exploitative. Though the attack itself takes up much of the film, its final stretch reveals it’s less concerned with attempting to make sense of what happened than what happens next to those who survive — some of whom struggle to find meaning and a will to go on.

1. Arrival (2016)

Even factoring in both Dunes, Arrival remains the ultimate example of Villeneuve’s skill telling the biggest and smallest possible stories at once. Adapted by screenwriter Eric Heisserer from a short story by Ted Chiang, the film stars Amy Adams as Louise, a linguist called into action when 12 mysterious spacecraft make an unexpected appearance across the globe. Beautifully shot by Bradford Young, the film uses spooky grays and earthy greens to create an uneasy mood that only intensifies as it progresses. It also features a sci-fi rarity: aliens that seem truly alien. The come in the form of cephalopod-like creatures of obvious intelligence but with motives made indiscernible by a mode of communication completely at odds with human experience. The need to communicate turns into a race against time as the ships and their mysterious pilots trigger a global crisis that threatens to tip over into catastrophe. Despite those stakes, and in ways best left unrevealed for those who haven’t seen the movie, Arrival remains Louise’s story, both in its emphasis on communication and understanding and its underlying concern with fate and the way life is inextricable with death. Fitting for a film in which history moves in a circle, which has been a Villeneuve concern since August 32nd on Earth and seems likely to remain one for the length of what’s been an unpredictable career.