In this article

Is the franchise era over? In 2023, a slew of superhero movies earned hundreds of millions of dollars at the box office each and still reportedly failed to make back the money required to produce and market them. Not even Tom Cruise, 2022’s box office savior, could rescue a Mission: Impossible movie from the installment fatigue that has set in across multiplexes — a kind of invasive exhaustion that’s made even the most reliable (or put another way, formulaic) of animated features falter in theaters. All this uncertainty raises a natural question: If franchises are dead, what’s next?

As our critics thumbed through the many, many movie releases of 2023 to determine their favorites from the past year, that question loomed. Are there hints for what’s to come, post-Barbenheimer, in the kinds of films that broke through for them when a Paul Rudd–led Marvel title couldn’t? Greta Gerwig’s and Christopher Nolan’s historic releases perhaps provide some clues, though only one of them made our critics’ top-10 lists. In the end, after sifting through the tumult, Bilge Ebiri and Alison Willmore landed on 10 very different films each — not one movie choice made the other’s list. Still, there are similarities: Filmmakers with a penchant for autobiography made both records, movies that clock the existential confusion of being locked inside a career did too. And in a year when it feels safer than ever to say superhero movies are throttling toward their own demise, one of them ended up in our top 20. Perhaps the best answer to what comes next is, simply, more chaos.

Bilge Ebiri’s Top 10 Films

10.

Anatomy of a Fall

Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or–winning courtroom drama, about a woman accused of killing her husband after he falls to his death in suspicious fashion, would be gripping enough as a procedural. But it gains transcendence as it begins to question the very nature of truth. Reality, we understand, is something different for each individual, an idea that has particular power in the world today. Anatomy of a Fall, however, isn’t necessarily a Grand Statement About Our Times; Triet and her co-writer and partner, Arthur Harari, have surely imagined this more as an exploration of domestic conflict than anything else. But their observational acuity, their fidelity to life as it’s lived — along with Sandra Huller’s entrancing lead performance — results in something that keeps exploding in the mind long after the credits have rolled.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Anatomy of a Fall.

9.

Asteroid City

It should have been evident long ago that Wes Anderson’s brand of hyper-controlled whimsy was all an attempt to confront the unhinged madness of the world. And none of us should have been surprised that his work became even more peculiar and more precise as the world became more and more insane. Maybe that’s why Asteroid City feels like such a signature work. Anderson doubles down on his style (how is that even possible at this point?) and gives us a maze-like network of framing devices to tell a story about a group of teenage scientists and their traumatized parents confronting an alien life form in the 1950s. Or wait, is it actually a story about the Actors Studio and turn-of-the-century American theater’s attempt to wrestle with the intricacies of the human heart? Or maybe these are the same thing. Anderson uses all the technique at his disposal to create a beautiful diorama of a world he cannot understand. In the end, isn’t that what great art does?

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Asteroid City and Matt Zoller Seitz’s revealing tour of Wes Anderson’s office.

8.

Passages

Ira Sachs is a master of the small, delicate gestures that wind up having seismic repercussions in our lives. In Passages, which might be his masterpiece, he fashions the most delectably ruinous of love triangles. A German filmmaker (Franz Rogowski) cheats on his husband (Ben Whishaw) with a woman (Adèle Exarchopoulos), falls in love with her, then begins to have second thoughts as the specter of commitment looms. Rogowski’s character is a total narcissist — a needy, callous, pathetic, selfish chaos agent — but go figure, he’s also quite irresistible. We’re drawn to this man despite the emotional devastation he wreaks, maybe because we sense something of ourselves in him. His destructive immaturity is captivating and relatable.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Passages.

7.

Fallen Leaves

Many of the year’s best films capture the queasy uncertainty of living in this moment, but few do it with such oblique charm as Aki Kaurismaki in this understated romance following two lonely, mismatched souls who keep missing each other. Kaurismaki’s style — somehow both deadpan and tender — is timeless, and one could argue that his stories could be taking place at any moment in history. But look at the ways in which his characters constantly seem on the verge of being tossed aside by the post-human, industrial landscape of Helsinki, and listen to the way that the music on the radio has been replaced by news reports about the war in Ukraine. The world has no place for the individual. And yet here we still are, persisting and yearning and drinking and stewing and fumbling our way through.

6.

Origin

Ava Duvernay has been so ever-present in the public eye that it’s wild to think this is her first feature film in five years, not to mention her first drama — the genre she truly excels at — in nearly a decade. She adapts Isabel Wilkerson’s monumental nonfiction study Caste as a cross between a historical mystery and a memoir, making the writer (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) her protagonist. Thus, we see the personal tragedies Wilkerson dealt with during her research, which adds an emotional urgency to her journey. But the film’s real power lies in Duvernay’s ability to jump across historical events, anecdotes, and images, forging connections that are at times revelatory and devastating, creating something that at times feels like both essay film and melodrama.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Origin.

5.

About Dry Grasses

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s films were never not ambitious, but they’ve become even more so over the years, all the while remaining confined to the rural Turkish small towns whose lives the director chronicles so well. His latest, clocking in at a mesmerizing 197 minutes, follows a middle school teacher (Deniz Celiloglu) whose attitude toward the people around him — be they students, fellow teachers, or ordinary citizens — is alternately patronizing, compassionate, and contemptuous. Not unlike with Passages, at times one wonders if this film could have been titled The Worst Person in the World, even as it’s clear that the filmmaker recognizes much of himself in the protagonist. Ceylan has never been a directly political filmmaker, but About Dry Grasses provides an astute analysis of the modern Turkish intellectual’s place in society, in all its infuriating complications, its social paralysis, and self-defeating self-absorption.

4.

Perfect Days

Wim Wenders released two marvelous films this year (his 3-D documentary Anselm was another triumph, though it just missed my list) and I hope he makes at least a dozen more pictures before he’s through. But in some ways, Perfect Days represents a culmination of the director’s journey. Wenders’s restless, angst-ridden protagonists have always been searching for blissful oblivion. These weren’t ambitious characters but rather people looking for a center. All those road movies — where were they headed? Perfect Days provides a kind of answer. A quiet, middle-aged man lives in a modest Tokyo home, gets up every morning and goes about his day cleaning the city’s toilets. There are hints of a past heartbreak, but they’re nothing more than gentle nods to the fact that all of us come from somewhere. There’s no sense that this person needs to do more, no sense that his life is being wasted. If anything, he is more aware of how lucky he is to be here than any of us. Is this what happiness looks like?

Read Bilge Ebiri’s interview with Wim Wenders.

3.

Ferrari

Once upon a time, Michael Mann was the king of composed beauty — a director of impeccable frames, of telling postures, of ethereal moods. Over the years, especially as he began to experiment with digital video, his work became more frenetic, more abstract, more reflective of the cacophony of our many-screened visual culture. In Ferrari, a project he’s been trying to realize for several decades, he brings the different sides of his directorial persona together, creating a film that veers between classicism in its domestic scenes and rip-roaring kineticism in its racing scenes. It’s all held together beautifully by Adam Driver as the aging Enzo Ferrari and Penélope Cruz as his wife, Laura, grieving parents and feuding spouses locked in tight emotional combat.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Ferrari, interview with Michael Mann, and Rachel Handler’s report from the Venice Film Festival.

2.

The Holdovers

Like a warm blanket made of asbestos, Alexander Payne’s comedy-drama about winter break at a boys’ boarding school has a cozy surface familiarity that’s slowly revealed to be toxic. Paul Giamatti — an actor who cannot be compared to any other actor in human history, in any medium — plays a history teacher living resolutely in the past. The stellar Da’Vine Joy Randolph is the grieving head cook who can neither move forward nor look back, and lightning-bolt newcomer Dominic Sessa is a troubled, unloved teen hurtling headlong into an uncertain future. Payne’s fondness for quiet, casual moments blends well with the film’s lo-fi aesthetic, which mimics the textures of a picture from the 1970s. This also means that formally, the movie is fixated on the past the way Giamatti’s character is. Even the nods to the Vietnam War throughout play like coy references to a controversial subject, as they would have been in 1970. Nevertheless, growth is possible. In Payne’s work, one individual’s foibles and failings can open another’s perception; his humans lead not by example, but through their flaws. This is one of the director’s greatest films.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of The Holdovers and Matthew Jacobs’s interview with Da’Vine Joy Randolph.

1.

Oppenheimer

So many biopics tried this year not to be biopics, to the point that the films’ publicists politely but firmly requested that we not call them biopics. Christopher Nolan didn’t seem to have any such worries. Oppenheimer is a proud biopic: a dense, big-swing condensation of a 600-page biography about one of the most important men of the 20th century and about (in the movie’s own words) “the most important fucking thing to ever happen in the history of the world.” But Oppenheimer is also the opposite of a standard-issue Great Man movie: The achievement here is monstrous, and the psychic dissolution of the main character before our very eyes is heartbreaking. Nolan wants to enter J. Robert Oppenheimer’s mind, to see the “hidden universe” that quantum physics opened up and thus convey the psychic prison in which the scientist found himself after ushering in the nuclear age. That the director turned this most devastating of stories into a riveting pop culture phenomenon without ceding one inch on its tragic dimensions is surely an achievement for the ages.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Oppenheimer and Bilge Ebiri’s explanation of the ending with Christopher Nolan.

Alison Willmore’s Top 10 Films

10.

The Outwaters

All of horror’s liveliest developments bubbled up from the genre’s raw edges this year — and, more than anything, from the internet. A24’s hit Talk to Me was the product of two Australian YouTubers, while Kyle Edward Ball’s Skinamarink was born out of creepy-pasta tropes and liminal spaces videos. But it’s another debut, Robbie Banfitch’s found-footage Mojave Desert freakout The Outwaters, that’s stubbornly stuck with me for months, and I only heard about it because of how much it polarized horror fans online. Made for a reported $15,000, and heavily improvised, The Outwaters sounds Blair Witch–like on paper, down to the camping trip its group of four friends is taking. But the actual experience of watching it is an astonishing array of dreamlike imagery as the trip goes from mundane to macabre. A stranger’s bloody limbs glimpsed by flashlight at night give way to sights that are even more disturbing in the harsh daylight, and Banfitch, who also stars in the film, appears at different times to be a victim of whatever’s happening and one of its perpetrators. He may not be working with much by way of resources, but what he accomplishes in this borderline experimental movie knocked my socks off — never more so than the moment when his protagonist somehow finds himself on the wing of a plane like the one he takes home at the start of the film, as though he’s always been caught in this nightmare and only now sees it.

9.

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3

James Gunn has headed off to the unenviable job of getting another superhero house in order at a corporation that’s willing to etherize even his own movie for tax purposes. But before he did, he demonstrated that he’s the best thing that ever happened to the MCU — not that I really needed the reminder as someone who’s always been hugely susceptible to his signature mix of the profane, the brutal, the sentimental, and the unexpectedly sublime. The decade’s most dominant genre has calcified into not just a formula but an ongoing advertisement for itself that viewers are expected to be grateful to pay for, and in the face of that, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 manages to be more than honest-to-god entertainment, one that has the liberated weirdness of material (like a stealth We3 adaptation) that was never expected to find a mass audiences. It even makes Chris Pratt likable as it brings Star-Lord full circle, from a kid who runs away from grief into the eternal arrested development of a space opera into an adult who finally goes home.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 and Siddhant Adlakha’s explanation of the ending.

8.

Happer’s Comet

Most of the films that were shot during the pandemic retain some essence of the pandemic, whether it has anything to do with what’s onscreen or not. But this 62-minute feature, which is enveloping as the lush night in which it takes place, somehow doesn’t, despite being shot in 2020 after filmmaker Tyler Taormina moved back to his childhood home on Long Island. Happer’s Comet feels, instead, untethered from any particular moment, a dialogue-free tribute to the isolation of suburbia that manages to feel as luxurious as it does lonely. The film skips through space, capturing snapshots rather than trying to assemble anything resembling a story. An older woman takes a break from leafing through a flier to lay her head on her dining room table and smile; a mechanic staffing an auto-body shop with no company except the tinny sound of a radio drops down and starts doing push-ups; a dog sits in a living room watching an off-screen television. Taormina’s images are as undeniably beautiful as they are eerie — the streetlamps and taillights of a parked car glow with equal warmth on an quiet road — but it’s the solitude they exude that makes them so inviting, as though getting a peek into a million private moments. As characters strap on roller skates and go wheeling out into the dark streets, it feels unclear if what’s motivating them is a desire for company or a chance to revel in the indulgence of all those empty spaces.

7.

A Thousand and One

A. V. Rockwell’s first film has the sweep of a novel and the fiercest of spirits, and it’s anchored by a remarkable performance by Teyana Taylor as the resolute Inez de la Paz. Fresh from Rikers in 1994, Inez promptly kidnaps her son, Terry, from a neglectful foster situation in Brooklyn and spirits him uptown to Harlem, where she grew up, and where she’ll eventually link up with an ex, Lucky (William Catlett), in a development that, like most of the ones in the film, doesn’t lead at all where you might expect. A Thousand and One is a gorgeous, moving work about people trying to carve out a family life for themselves with no models to pull from and in the face of a city that becomes increasingly hostile to their existence with every supposed improvement and who fuck up and hurt each other and keep going, because the only other option is to give up. Even while dealing in larger themes, Rockwell always lets her characters lead the way — they are never anything less than vividly alive as they make their way through a teeming metropolis it’s all too easy to disappear into.

Read Alison Willmore’s review of A Thousand and One.

6.

Reality

There’s a formal rigor to playwright Tina Satter’s directorial debut that contrasts starkly with the panicky, pulse-fluttering experience of actually watching it. Satter took her dialogue verbatim from the transcripts of whistleblower Reality Winner’s interrogation by the FBI on June 3, 2017, the day of her arrest, redactions and all — when the film gets to a line that was blacked out, the actors glitch out and briefly vanish from the frame, as though their actual performances had been temporarily excised by the State. And yet there’s nothing removed about Sydney Sweeney’s performance as Reality, which unfolds in micro-expressions as her character tries to pretend — or will herself to believe — that what’s happening to her isn’t such a big deal. As men pour into Reality’s shitty Augusta, Georgia, rental house and start documenting the minutiae of her life, the camera closes in on Sweeney’s increasingly stricken face as though trying to peer into her character’s head. It’s a claustrophobic, masterful work that, in the space of 82 minutes, allows you to witness in intimate detail a young woman’s life getting imploded by the might of the State.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Reality.

5.

The Zone of Interest

Jonathan Glazer’s film portrays a key figure in the Holocaust not as the embodiment of virulent hatred but as a product of compartmentalization and ambition, which turns out to be even more disturbing. I’m not sure there is a viewing experience this year that is simultaneously as stunning and stifling as The Zone of Interest, which subjects you to the bourgeois aspirations and careerist angst of Rudolf (Christian Friedel) and Hedwig Höss (Sandra Hüller), who’ve achieved their dream home right next to the death camp at Auschwitz, which Rudolf oversees. The austerity of Glazer’s approach is unforgiving, presenting the mundanity of the Höss’s concerns, from Hedwig’s pride in her garden to the transfer Rudolf is given that Hedwig refuses to accompany him during, against an always-present-but-never-peered-into backdrop of atrocity. The horror next door only occasionally manages to intrude into carefully partitioned-off consciousnesses of the family, as when a swimming trip with the children is cut short by an encounter with some of the gruesome by-products of the camp. But in a late scene that connects his film to Joshua Oppenheimer’s crucial documentary The Act of Killing, Glazer posits that sometimes the body can revolt against the brutal truths the mind tries to tamp down.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of The Zone of Interest.

4.

The Boy and the Heron

Leave it to Hayao Miyazaki to pack so much mourning, self-doubt, resentment, and hope into a movie about a secret kingdom filled with winsome, ravenous anthropomorphic birds. There’s more to The Boy and the Heron than that, of course, including a backdrop of World War II Japan, autobiographical resonances, a pregnant stepmother who’s also an aunt, a gray heron who’s also a grouchy man, and the dream logic of the ocean-dominated otherworld where souls rise up as adorable spirits to be born into our reality. But what’s so compelling about Miyazaki’s epic latest, which will hopefully also not be his last, is the way that the magical serves as an emotional allegory for what 12-year-old Mahito (Soma Santoki) is going through rather than something literal. Mahito’s wizardlike granduncle retreated from reality to create a beguiling but unsteady alternate universe that he needs someone “free of malice” to take over. The Boy and the Heron is about accepting loss but also accepting that you are part of the world, in all its brokenness and all its potential.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of The Boy and the Heron.

3.

Tótem

Lila Avilés’s dazzling family drama takes place over a single day, during which the relatives of a 7-year-old girl named Sol (Naíma Sentíes) gather at her grandfather’s house to throw a surprise birthday party for her father, Tona (Mateo García Elizondo). That Tona is likely to die soon from the cancer that’s reduced him to a husk is clear to everyone except Tótem’s young protagonist, who struggles to understand why her dad doesn’t always want to see her (or anyone) and tries to make sense of the behavior of the grief-stricken grown-ups around her. Avilés’s film combines the avid curiosity of a child with the steady wisdom of an adult, and as it whirls through party prep and the bickering of family members — over a cake, over the bathroom, over Tona’s decision to forgo treatment, over a spiritualist brought in to cleanse the home — it approaches its large ensemble of characters with a tenderness that’s almost unbearable. Without ever verging on cloying, it’s a film about death that becomes a heartfelt celebration of life.

2.

May December

Todd Haynes’s latest is a brilliant ode to female toxicity that begins at a place of camp and ends at one that’s closer to horror. The Mary Kay Letourneau–inspired Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Julianne Moore) lisps and bakes and enforces her desired illusion of fairy-tale domesticity by way of a high-femme terrorism that involves weaponized tears and velvet barbs winged at her family members. As Elizabeth Berry, the actor set to play Gracie in an upcoming movie, Natalie Portman is all careful platitudes and hungry eyes, talking a big game about doing justice to the story of how a 36-year-old Gracie seduced the then-13 Joe Yoo (Charles Melton), who she later married, while barely concealing her ravenous glee at the ripeness of the material she’s harvesting. Haynes showcases these dueling characters and the outsize performances behind them with an appreciative wryness that’s deceptive (as Moore opens the fridge, the score lets loose with a dramatic twang before she observes “I don’t think we have enough hot dogs”). It’s Joe who emerges as the film’s wounded soul, played by an impressive Melton as a 30-something man frozen somewhere in adolescence by his experiences, blinking in disbelief at the life he’s found himself in as though just waking up to the reality of what happened to him. It’s a heartbreaking turn, and the way it’s deployed onscreen makes May December the year’s most complex and layered watch.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review on May December and Madeline Leung Coleman’s interview with Todd Haynes.

1.

Showing Up

This year has given me a lot of “the old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born” feelings about the movies, between the contraction of the streaming model (which maybe never made sense to begin with in terms of profitability?), the floundering of Disney, the faltering of once-massive franchises, the triumphant labor movements, and the incursion of pop stars into the multiplexes. I’m hardly mourning the corporate structures that have dominated the last decade plus, but I have no idea what comes next. I just know that there’s been no better movie to encapsulate the year, and no better movie, period, than Kelly Reichardt’s matchless Showing Up, which is all about making art in a world that also requires you to make money. As Lizzy, a sculptor and admin assistant at a real arts college that (a little too fittingly) went under a few years ago for financial reasons, Michelle Williams has the perfectly pinched aura of a bluestocking dropped in sun-dappled present-day Portland. But her concerns — her ability to make her delicate clay sculptures of little ladies while also balancing a day job, the enviable self-interest of her frenemy-rival artist-landlord Jo (a delightful Hong Chau) — are palpable enough to feel like they could belong to Reichardt herself, the pressing intertwined with the petty in ways that are deeply relatable. Is it possible to support yourself and still have enough left over to do the work you love? Showing Up, which also features a turn from passion project flautist André Benjamin, doesn’t have an answer. What it does have is an inexpressibly lovely affirmation of the meaning of making art that you believe in, even if it only reaches a select but appreciative audience. Good job, girls.

A Year of Movie Endings

This year saw several major superhero movies go bust (and as of this writing, we don’t know if Aquaman will be another one). It saw Disney deliver one bona fide animated flop (Wish) and another that exists in the liminal space between flop and hit (Elemental). We also saw Netflix starting to pull back on the mountains of money it throws toward film productions. Many of us have been anticipating (maybe even hoping for) the end of the franchise era. But now that it might be happening, what lies on the other side?

Other Movie Highlights From This Year

Throughout 2023, our critics maintained “Best Movies of the Year (So Far)” lists. Some of those selections appear above in our Top 10 picks. Below are more of the films (but not all) that stood out to them this year.

Boudica, Queen of War

Low-budget action master Jessie V. Johnson directed this down-and-dirty period slaughterfest about a woman who becomes a powerful warrior after her husband, the leader of the Iceni, is killed by the Romans. As the title character, a legendary figure in ancient British history, the great Olga Kurylenko convincingly goes from meek, tender, and deferential to mad, snarling, and murderous. Don’t expect much historical analysis or period accuracy or emotional nuance; this one works on your lizard brain. It’s like a dimestore Braveheart: It might not have the sweep of those old-school period action films, but it’s still thrilling and passionate and filled with bloodcurdling, wall-to-wall violence. —B.E.

Four Daughters

Kaouther Ben Hania’s hybrid documentary has a remarkable conceit, telling the story of Olfa Hamrouni, a Tunisian mother, and her four daughters by restaging scenes from their eventful, terrifying lives. Two of the girls play themselves; the other two are played by actresses, because, as Olfa says, they “were devoured by the wolves.” What she actually means by that becomes clear over the course of the film (though Tunisians who remember this news item from recent history may know where the story goes), as we learn about Olfa’s marriage, the abuse in her family, and how her daughters gradually embraced a form of militant, fundamentalist Islam that tore their family apart. An actress is hired to play Olfa during the more difficult scenes, and we see dryly funny and slyly terrifying footage of the real Olfa coaching her double how to act. In telling the story of Olfa and her daughters, Ben Hania (whose 2019 film The Man Who Sold His Skin was nominated for an Oscar) is also telling the tumultuous story of Tunisia in the wake of the Arab Spring, a promising movement that began in that country before spreading to the rest of North Africa and the Middle East. —B.E.

Killers of the Flower Moon

It would be tempting to say that Killers of the Flower Moon is Martin Scorsese’s attempt at a western, and one could also see in it yet another gangster epic from a man who’s made his share of them. But in adapting David Grann’s acclaimed 2017 nonfiction history, about a yearslong conspiracy to murder members of the Osage nation in an effort to accrue their oil wealth, Scorsese and screenwriter Eric Roth have turned it into that simplest and slipperiest of things: the story of a marriage. The film is at its best when showing the growing relationship between Mollie Brown (Lily Gladstone), a member of a large and wealthy Osage family, and Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), a WWI veteran who arrives in town to work for his uncle, William Hale (Robert De Niro), a local godfather type. The most uncomfortable aspect of Killers of the Flower Moon is not the spectacular criminality on display but rather how it’s treated by so many of the characters as no big deal. These are typically Scorsesean ideas: our offhand capacity for evil, the inherent violence of relationships, the strain of serving two masters. In so many ways, though, this is Lily Gladstone’s movie. She plays Mollie with a mix of standoffishness and exhausted hope. As the horrors mount around her, she navigates her queasy, gathering suspicions as well as her affection for her husband. When he tells Mollie he loves her, she believes him. And so do we. That is, in many ways, the great, cruel, unreconciled tragedy at the heart of this tale. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Killers of the Flower Moon and Alison Willmore’s profile of Lily Gladstone.

Delinquents

Argentine director Rodrigo Moreno’s film is being billed as a heist movie, which is not technically incorrect; it is, in fact, about a man who robs a bank and then coaxes a co-worker into an elaborate scheme to get away with it. But at heart, The Delinquents is about leaving an oppressive world behind and discovering the possibility of freedom in a new one. The thieves here are not looking to get rich. “Three and a half years in jail, or 25 at the bank?” is how Morán (Daniel Elias) puts it to his colleague Román (Esteban Bigliardi), explaining why he’s resorted to crime. The plan is quite simple: Morán will confess to the robbery and get three years in prison. Román will hide the money in the meantime. Afterward, the two men will have just enough to not have to work for a living. But is such a goal, such a world, even possible? Moreno’s film is really about the wait in between, about what happens as these two men bide their time. Clocking in at 183 minutes, this is a movie of detours both narrative and formal. But it’s never boring or tedious. The Delinquents works its magic on us the way that the promise of freedom works on its characters. It’s a vision of a life unlived — as impossible as it is intoxicating. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of The Delinquents.

When Evil Lurks

This brutal Argentine horror film takes place in a reality in which possessions are both known and spreadable, transforming the infected into malevolent, oozing masses of flesh that are referred to as “Rottens.” But what makes Demián Rugna’s film so effective is not the gore (which is appropriately gross!) or the idea of a demonic contagion — it’s the way that the weaknesses of human nature, on both a personal and a systemic level, make stopping the corruption almost impossible once it appears. When a Rotten turns up on land near the farm owned by brothers Pedro (Ezequiel Rodríguez) and Jaime (Demián Salomon), the local authorities pass the buck while insisting that everyone is overreacting. But Pedro, the closest thing the film has to a hero, is anything but. He ends up doing more damage in his flailing efforts to help and to save his children, a sequence that plays like a grim comedy of errors. Rugna was apparently inspired by health issues caused by pesticide in his native country, though the film’s combination of misinformation, denial, and institutional failures invariably brings to mind the early days of COVID. —A.W.

The Creator

The artificial-intelligence framing is just bait — the robots in this sci-fi epic don’t actually have much bearing on our current conversations about ChatGPT. They are, instead, multifaceted metaphors for all sorts of groups that get othered, and the focus of Gareth Edwards’s unexpectedly grown-up movie is less the AIs themselves than how they’re treated by the American forces that are battling to wipe them from existence. The Creator riffs on both Vietnam War movies and Blade Runner as it sends a never-better John David Washington into a war-torn Southeast Asia to look for the woman (Gemma Chan) he loved and betrayed, never seeming sure as to what he would say if he found her. Edwards, always good with visual effects, offers up stunning, lived-in landscapes in which brutalist metal towers coexist alongside paddy fields and villages. —A.W.

Read Alison Wilmore’s full review of The Creator.

Our Body

Documentarian Claire Simon explains what she’s setting out to do at the start of the astonishing Our Body — to explore the “mostly female world” of the women’s health ward of a Parisian hospital, “treating the gynecological pathologies that weigh down on our lives, on our loves, on our hopes, on our desires.” Over the course of her almost three-hour film, she turns her camera to moments of vulnerability, sorrow, and joy as a woman records the voice of her crying newborn after giving birth alone, as a trans teenager learns he’ll have to wait until he’s 18 to go ahead with medical procedures his father refuses to consent to, and as a young woman weeps while talking about the pain she’s started experiencing during sex with her new husband. There’s an expansive generosity to the film, and to the willingness of its subjects to allow these moments to be documented, that’s met with the same openness from Simon when a diagnosis means that she’s no longer just the director but a patient herself. —A.W.

The Origin of Evil

Sebastien Marnier’s slow-boiling thriller weaves such a mood of sinister duplicity that you might want to take a shower afterward. It follows Stephane (Laure Calamy), a cannery worker with a girlfriend in prison, who reconnects with Serge (Jacques Weber), the wealthy businessman she claims is her father. Serge’s family is immediately suspicious, but it’s clear they’ve got their own designs on the man’s wealth. Everybody in this movie seems to be lying through their teeth. In less sure hands, this could have resulted in annoyance. But Marnier and his terrific cast know just how much to reveal and when. They keep us delightfully unmoored. —B.E.

A Haunting in Venice

Kenneth Branagh’s Hercule Poirot mysteries haven’t exactly set the film world on fire, so the fact that the director-star continues to make them clearly speaks to his love for these stories and this character. In the latest, A Haunting in Venice, he forsakes the swooping cameras and epic vistas and frantic pacing of the previous films for something stranger, more insular, and maybe even more refined. He takes Agatha Christie’s little-discussed 1969 novel, Hallowe’en Party, and turns it into a moody, staccato thriller about the unknown. He also takes quite a few liberties with the original along the way, transporting the story to Venice in 1947 and bringing in a supernatural undercurrent. This allows for some jump-scares, but it also makes Poirot more intriguing: His refusal to believe in matters of the spirit isn’t just due to his devotion to science and reason — it’s also a measure of his brokenness. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of A Haunting in Venice.

El Conde

Pablo Larraín’s latest film presents General Augusto Pinochet, the brutal, U.S.-backed military dictator who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990 and died in 2006, still with the blood of thousands on his hands, as a literal vampire. So, what is it? Horror? Satire? Allegory? Political thriller? Family drama? It’s got all these elements in it, but it’s also very much its own thing — an elegantly shot film whose competing tones create something delirious and new. But beneath all the genre theatrics, what comes through most vividly in El Conde are Larraín’s sadness and rage at what happened to his country. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of El Conde.

Bottoms

If anything, Emma Seligman’s follow-up to Shiva Baby could be even more anarchic, but as is, it’s a blissfully silly, unabashedly violent, and often daring time. Rachel Sennott and Ayo Edebiri are a comedy duo for the ages as PJ and Josie, lesbian outcasts who found a women’s self-defense class/fight club at their high school and accidentally create a space for feminist solidarity, though the two of them are just trying to get laid. Both are very funny, and the cast features other standouts too — like Marshawn Lynch as the club’s soon-to-be-divorced adviser and Kaia Gerber as the school’s second-most-popular cheerleader. —A.W.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Bottoms.

The Beasts

In Rodrigo Sorogoyen’s absorbing, suspenseful drama, a French couple attempt to start an organic farm and rehabilitate a desolate stretch of property in a rural Spanish village. But the locals, who are trying to sell their land off for development by a wind-energy company, see the couple as stuck-up foreigners trying to prevent them from making money and leaving this place. Sorogoyen might give lip service to the economic realities underlying the land dispute, but he’s also not afraid to take sides and to entertain. As the growing hostility between the man and woman and their neighbors eventually reaches Straw Dogs–esque proportions, it becomes clear the director wants to make us feel his protagonists’ growing helplessness and the gnawing tension of living right next door to people who might genuinely want to kill you. —B.E.

Barbie

Directed and co-written by Greta Gerwig, Barbie has become a Rorschach-inkblot purity test about feminism, womanhood, and the state of the industry itself. Is Barbie feminist or is it merely a marker of capitalism’s cunning, taking the emblems but not of the soul of the feminist movement? Is it just a slick toy commercial or is it actually reckoning with the cultural weight of Barbie with wit? I think the truth is rather complex, making Barbie operate as a woman’s picture, a feminist argument, and film defined by its delirious interest in the pleasure principle. No matter where you’ve drawn your lines on this cultural battlefield, it’s hard to deny that Barbie is fun as hell. Led by star-producer Margot Robbie, Barbie is a pink funhouse brimming with glittering dance numbers, heartfelt monologues, and a genuine curiosity about not just womanhood but humanity itself. Everyone in the cast brings their A-game. Ryan Gosling undoubtedly has the boldest performance as the yearning himbo Ken, whose entire existence is in service of basking in Barbie’s warm gaze. Issa Rae and Hari Nef are equal delights for some deranged line readings alone. America Ferrera is the stealth MVP for her juicy monologue that extols the constrictions on women. Robbie cements her position as a true new star in Hollywood’s firmament by helping craft a film that has a capacious curiosity and joyful aesthetics that speak toward the wild, yearning nature of being alive. —A.J.B.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Barbie and Allison P. Davis’ essay about Greta Gerwig’s films.

They Cloned Tyrone

Juel Taylor’s genre-bending directorial debut is a vibrant, snappy melding of sci-fi concepts, social commentary, and blaxploitation homage with John Boyega, Jamie Foxx, and Teyonah Parris starring as broadly drawn types — a drug dealer, a pimp, and a sex worker — who discover that the seemingly inescapable patterns of their lives in a neighborhood called the Glen aren’t accidental and are actually the result of a government conspiracy. With so many Netflix original movies these days feeling like algorithmic filler, They Cloned Tyrone is the rare offering that doesn’t just feel like it’s made by a person but by someone with an eye for visual, a distinctive voice, and a sharp sense of humor. —A.W.

Afire

Forest fires rage in the distance in Christian Petzold’s entrancing film, which doesn’t stop its characters — novelist Leon (Thomas Schubert), photographer Felix (Langston Uibel), seasonal worker Nadja (Paula Beer), and rescue swimmer Devid (Enno Trebs) — from flirting and fighting over shared meals outside the beach house that’s Afire’s primary setting. Throughout the film, it’s Leon’s tetchiness over the failings of his second manuscript that threaten to derail the seaside idyll, but the potential for more serious danger always lurks in the background. The wonder of Petzold’s work is that it revels in the unblemished youthfulness of its characters while allowing that, in order to make great art, it helps to have endured some pain. —A.W.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Afire.

The Deepest Breath

Free-diving — trying to reach record depths by simply holding your breath and diving as far as you can — is one of the deadliest sports on the face of the Earth, and Laura McGann’s documentary has quite a challenge: How to tell its story without feeling like it’s exploiting a potential tragedy. The film opens with champion Italian diver Alessia Zecchini blacking out at the end of one of her dives, then flashes back across the years to show her love for the sport and her rise to the top, all the while interweaving the story of Stephen Keenan, an Irish free diver who eventually became an expert safety diver and coach. Those familiar with the story will know where it’s all headed. Others — that would be most viewers, probably — will wonder how these two lives will ultimately intersect. Documentary purists who balk at movies hiding real-life tragedies from their viewers until the end will probably break out in hives. But McGann doesn’t really hide the nature of her story. It’s clear pretty early on that we’re watching something harrowing. This is, ultimately, an elegant and deeply moving picture. —B.E.

Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning Part One

The latest Mission: Impossible movie, as suggested by that ominous “part one,” seems to care a bit more about its plot than previous entries, and it’s not hard to see why. This time, Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt isn’t fighting nihilistic terrorists or vaporous international-espionage networks but an all-powerful artificial intelligence known as “the Entity,” a variation on the man-versus-machine theme that Cruise pursued in last year’s Top Gun: Maverick. It’s also a rather compelling metaphor for the actor’s well-publicized dedication to old-school action filmmaking and real-life stunt work. But if Dead Reckoning spends a bit too much time slowly (and repeatedly) spelling out what the Entity is and what it can do and why that’s capital-B Bad, it can be forgiven, because all that exposition serves as a kind of spiritual justification for the bravado on display. And the film is filled with amazing action set pieces, including the star’s much-publicized death-defying motorcycle-parachute jump over — or rather into — an immense Norwegian canyon as well as the most hair-raising train derailment ever put to film. Whenever it gets down to the business of making Tom Cruise run and jump and drive and fly in and out of things, Dead Reckoning manages to astonish. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning Part One and Jason Bailey’s ranking of the best action sequences in the entire M:I franchise.

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny

Despite the spectacle of an effectively de-aged Harrison Ford walloping Nazis atop a train during World War II in its opening scenes, James Mangold’s film isn’t about the young Indiana Jones but about the aging and rather pathetic Dr. Henry Jones, now on the verge of retirement from teaching archaeology to sleepy Hunter College students, drinking himself silly in a grubby New York apartment. Into his life enters his goddaughter, Helena Shaw (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), the adventurous offspring of an old colleague, to drag him along on a chase for a contraption that can predict fissures in the very fabric of time, thereby allowing travel into the past. Not unlike The Force Awakens did with the original Star Wars, Dial of Destiny feels at times like a remix, offering variations on elements from earlier Indiana Jones movies. Mangold may not have the young Steven Spielberg’s musical flair for extravagant action choreography (who does?), but he is a tougher, leaner director, using a tighter frame and keeping his camera close. That may shortchange the escapist atmosphere and evocative exotica of the material, but it does bring a ground-level immediacy to the action. Plus all the vehicular mayhem probably suits this older, slower version of Indy, who fights less but often finds himself in the middle of any number of “wouldn’t it be cool if” chases: motorcycles and tuk-tuks and trains and Jaguars and horses and planes in all manner of arrangements and rearrangements as well as one delirious final sequence that had me giggling with delight. No, it’s not Raiders of the Lost Ark; no movie is. But it’s too entertaining to dismiss. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.

Scarlet

Pietro Marcello’s previous feature, 2020’s brilliant Martin Eden, was an ambitious adaptation that attempted to graft a Jack London novel onto the entire history of the 20th century. With Scarlet, he works in a gentler register, though the ambition is still there. In its opening scenes, a gruff, quiet man, Raphaël (Raphaël Thiéry), returns from World War I to discover that his wife is dead and that he has a young daughter. He and the girl live with a group of women who are outcasts from the community, and he soon becomes an outcast as well. This rough man’s daughter (played as a young woman by Juliette Jouan) turns out to be the most delicate of creatures, a romantic young woman with a connection to the divine. This beguiling film has the cadences of a fairy tale — prophetic visions, magical coincidences, behavior echoed across the years — but Marcello, who came up through the documentary world, expertly blends the immediate and the airy. —B.E.

Blue Jean

Georgia Oakley’s feature debut is an anguished look at life in the closet set in Northeast England in 1988 — the year the Thatcher administration introduced a set of laws banning the “promotion of homosexuality” in the name of protecting children. Jean, played by a terrific Rosy McEwen in her first leading role, has painstakingly compartmentalized her existence. At night, she hangs out at a lesbian bar with her girlfriend, Viv (Kerrie Hayes), a part of herself she keeps secret from her co-workers and students at the school where she works as a gym teacher in the day. Blue Jean is a moody, delicately wrought film about how Jean, damaged from past experiences and her own internalized homophobia, is unable to feel like she belongs in either of the worlds she created for herself. The justification for the impending legislation in the background of the film may sound all too familiar, but Blue Jean’s real power comes from its examination of the human costs of living in fear. —A.W.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

Not to be corny, but I teared up a few times during the opening scenes of this sequel to 2018’s Into the Spider-Verse just from how good it all looked. Somehow, the animation is even more impressive and imaginative, as the film gives us new universes done in soft watercolors and futuristic detail while also returning us to the embrace of the vibrant, comic-book-art–inspired Brooklyn that its teenage hero, Miles Morales (Shameik Moore), inhabits. Across the Spider-Verse ends on a to-be-continued, but it’s hard to complain about that when it’s so rich with detail and so beautifully crafted — a riff on multiverse storytelling that also becomes a heartfelt exploration of parenting and accepting that growing up means that your child is going to encounter pain you can’t shelter them from. —A.W.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse and Richard Newby’s explanation of the cliff-hanger ending.

Night of the 12th

Based on a real-life case, Dominik Moll’s thriller follows the lengthy investigation into the grisly burning death of a young woman in a small town near Grenoble. An opening title informs us that this was but one of many unsolved murders in France, a disquieting bit of information with which to kick off a mystery, telling us there won’t be a final solution to the case. This subtly draws our attention to other aspects of the story: to the interactions among the cops investigating the case, to the humdrum bureaucracy of police work, and to a general feeling of haunted desolation in this provincial area nestled next to the French Alps. The film won six awards at this year’s César Awards, including Best Picture, Director, and Screenplay, but there seems to be very little buzz around its U.S. release. Even so, it feels major, with an unsettling mood that recalls such previous policier masterpieces as David Fincher’s Zodiac and Bong Joon Ho’s Memories of Murder. Its real-world mysteries eventually become existential ones, but the movie never stops sending chills up your spine. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Night of the 12th.

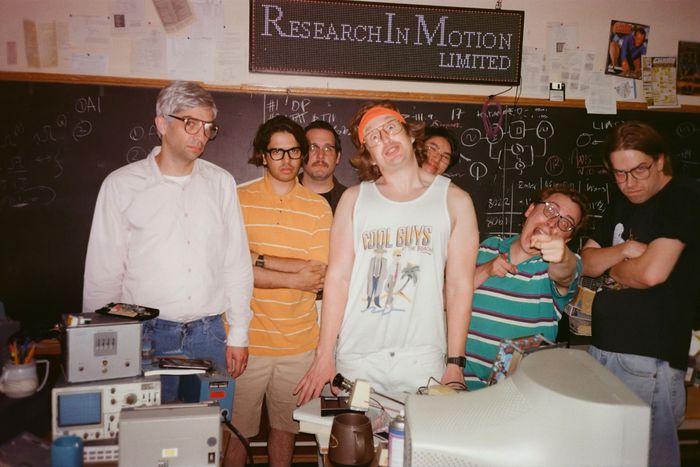

BlackBerry

As the ultracorporate “shark” Jim Balsillie, Glenn Howerton is a near-comical vision of drive and animalistic ambition, and his character turns out to be just who the clumsy, introverted nerds who founded Research in Motion (RIM), the tiny company that would transform the cell-phone industry, need to make their harebrained schemes reality. Directed by Matt Johnson, BlackBerry basically presents the rise of the smartphone as a sitcom pitch: What happens when two affable, not-ready-for-prime-time dorks from Waterloo, Canada — brilliant engineer Mike Lazaridis (Jay Baruchel) and his can-do cheerleader pal Doug Fregin (Johnson) — are joined by a crisply suited, Harvard-educated, phone-smashing apex predator. One of the great pleasures of BlackBerry is watching Balsillie’s befuddled, running disgust at Lazaridis and Fregin’s hapless ways, at the chaotic ineptitude of their finances, their utter lack of business sense, and their go-along-to-get-along management style. I would happily watch several seasons of these three going at it. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of BlackBerry.

Sisu

This is a largely wordless World War II thriller about a grizzled, haunted loner who strikes a massive vein of gold in the remote reaches of Lapland, only to find himself tormented by a platoon of retreating Nazis. The year is 1944, and the war is basically lost for the Germans, who are laying waste to everything in their path. As the Nazis chase him, our hero picks them off, sometimes individually and sometimes en masse. What keeps it from being repetitive and predictable is director Jalmari Helander’s increasingly creative ideas about how his hero should go about wasting the Nazis in his path, as the film graduates from humble head stabbings and limb snappings to more ambitious and explosive mayhem. So much so that it all starts to border on a philosophical treatise about survival and perseverance. Some will say Sisu recalls Mad Max: Fury Road or Inglourious Basterds, but I kept imagining it as what might have happened had Sergio Leone been alive to direct Crank: High Voltage. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Sisu.

The Eight Mountains

Like the characters in Brokeback Mountain, the men in this drama from Felix van Groeningen and Charlotte Vandermeersch bond during an Edenic summer in the wilderness, and while their relationship is platonic, the film is no less a love story. Pietro (Luca Marinelli) and Bruno (Alessandro Borghi) are childhood friends who reunite as adults to build a cabin up in the mountains where Bruno grew up and Pietro’s family used to spend the summers — a breathtaking location that becomes a place the two return to as the years pass. The Eight Mountains offers all sorts of ecstatically beautiful footage of the Italian Alps, but it also spins out a delicate, rueful story about trying to find a balance between nature and work, as its two characters take divergent routes in their search for a meaningful life. —A.W.

Quasi

The comedy troupe Broken Lizard met at Colgate back in 1989 and never spiritually left college. Thank God for that. Their work still feels like a group of amiable stoners from across the hall came up with a bunch of dumb, funny ideas to put into a movie and then filmed it all the following morning. A riff on The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Quasi may be their first period piece, but it’s basically the same vibes-based silliness. Steve Lemme plays Quasimodo, a torture-chamber employee who gets caught in a petty but murderous tiff between the pope and the king. One can easily imagine a version of this movie where the plot is handled with urgency, authenticity, and suspense, but then what would you be left with? The Broken Lizard guys understand that their brand of handmade, good-natured humor doesn’t really work with tighter storytelling or sharper acting, and they’ve honed their approach well over the years. They’re always winking at us because they know theirs is a fundamentally participatory style of comedy; the process is part of the joke. They keep making cult movies so that when you watch them, you feel as if you were there when they made them. Broken Lizard is all of us. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Quasi and a transcript of Vulture Festival’s Broken Lizard panel.

Suzume

Makoto Shinkai’s latest is another of the openhearted romantic fantasies he’s so good at, a road-trip adventure about an orphaned teenage girl who helps save Japan from a mythical worm whose intrusions into our world cause massive earthquakes. But despite featuring both a mysterious love interest and a talking cat, Suzume is a more pensive affair than it first appears, one that reflects what it means to come of age when the future feels so uncertain. Suzume (Nanoka Hara) and her companion, Souta (Hokuto Matsumura) — a dreamboat who, hilariously, spends most of his time magically transformed into a three-legged chair — cross the country trying to close up portals that open in areas that have been abandoned because of disasters or the shrinking population, as though patching up the tears in a social fabric that’s wearing thin all over. It’s a swoony, gorgeously animated movie that earns its sadness as well as its ecstatic bursts of hope. —A.W.

Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Suzume and Rafael Motamayor’s interview with Makoto Shinkai.

Sick of Myself

It’s possible that no scene this year will be more entertaining than the one in which Signe (Kristine Kujath Thorp), a Norwegian woman with a pathological need to be the center of attention, lies to the chef at a fancy dinner about having severe nut allergies, then forgets she said that and eats something with nuts while the whole table looks on in horrified expectation. But then, all of this Kristoffer Borgli movie is like that — a bitterly funny black comedy about narcissism and the paths people attempt to take to fame. When Signe’s boyfriend, Thomas (Eirik Sæther), rises thanks to a dubious artistic career involving stolen furniture, Signe retaliates by taking a recalled Russian drug whose side effects include a horrifying skin condition. The perfectly paired sociopaths ricochet through Oslo as though each is involved in their own elaborate stunt that never actually ends. —A.W.

Air

Air, Ben Affleck’s enormously entertaining corporate drama about Nike’s efforts to sign Michael Jordan, might seem at first like a ridiculous idea for a movie, but it is in fact an ingenious one. The creation of the Air Jordan sneaker changed pop culture forever, and Jordan’s unprecedented profit-sharing deal with Nike would give athletes equity in the products they were being used to sell. The film situates the Air Jordan as a product of the runaway consumerism of the 1980s, but it also hints at a boundless, complex new world coming into view. In what will surely go down in history as one of the great sports-movie speeches, Sonny Vaccaro (Matt Damon), the executive in charge of the shoe company’s basketball outreach, makes the point to Michael himself that the player practically exists outside of space and time. “Everyone at this table will be forgotten,” he says, noting all the executives gathered around them. “Except for you.” —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of Air, Chris Lee’s behind-the-scenes story about screenwriter Alex Convery, and Derek Lawrence’s interview with actor Chris Messina.

Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

In attempting to turn the classic fantasy role-playing game into a franchise picture, directors John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein somehow manage to play to the base while acknowledging the inherent ridiculousness and impenetrability of the concept. Their film is filled with medieval derring-do, unpronounceable fantasyspeak, and what I can only assume is a cornucopia of nerdtastic Easter eggs. But it’s also hilarious, with a game cast led by Chris Pine, a leading man who has turned making fun of his own leading manness into an art form. The film’s set pieces are built around comedy, with bits of (cleverly choreographed and directed) action to add some urgency, not the other way around. And the humor actually helps to up the suspense. Honor Among Thieves is the work of filmmakers who understand that the best way to take stuff like this seriously is not to take it seriously at all, and to have fun with it. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves.

John Wick: Chapter 4

John Wick: Chapter 4 is blissfully entertaining, full of pratfalls and acting turns that make audiences swell with oohs, aahs, and yelps. It’s far more narratively focused than its previous sequels, while still managing to globe-trot a behemoth cast à la Chapter 2 and Chapter 3. Here, John Wick (Keanu Reeves) seeks to finally buy his freedom by dueling the Marquis (Bill Skarsgård). I have some reservations about the narrative choices, but the cinematic violence of Chapter 4 brought me the joy and erotic rush that has long powered the series. It synthesizes the zaniness of Looney Tunes and gags of Buster Keaton with martial-arts master classes that call back to the career of Jackie Chan and learn from more recent films like 2017’s South Korean action flick The Villainess. It’s a history lesson on what the body can do onscreen — its limits and its wonders. —A.J.B.

Read Angelica Jade Bastién’s review of John Wick: Chapter 4, Chris Lee’s interview with filmmaker Chad Stahelski, and Bilge Ebiri’s analysis of the movie’s ending.

The Lost King

This is the lightly fictionalized (and amazing) story of amateur historian Philippa Langley (Sally Hawkins), who in 2012 helped lead an archaeological expedition that dug up a nondescript Leicester car park and unearthed the remains of the notorious King Richard III. The bulk of the film tells of how Philippa came to be fascinated by the disgraced medieval monarch and fought not just to find his grave but also to counter the prevailing villainous narrative about him, which may well have been the work of Tudor propagandists. There’s an interesting tension in the film, between the exaltation of royal power on the one hand — a spiritual belief in the magic of lineage, itself dating back to arcane notions of divine right — and, on the other, the ennobling of common individuals, of ordinary people like Philippa as they butt heads with city councils and university administrators and academic mossbacks. The very act of reclaiming Richard’s legacy from his now-gone Tudor rivals puts the lie to the very idea of royalty, of bloodlines, and the eternal question of who gets to have power over whom. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of The Lost King.

Tori and Lokita

The latest from award-winning, veteran Belgian realists Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne follows two African migrants in Belgium: 17-year-old Lokita (Joely Mbundu) and her 11-year-old “brother,” Tori (Pablo Schils). They’re not actually siblings. They’re not even from the same country. But they’ve formed an almost mystically strong bond ever since they met during their crossing to Europe and have now become inseparable. For all the sensitivity and sobriety of their work, what has made the Dardennes such effective filmmakers has been the subtle way they insert genre elements into their dramas. Each movie could be thought of as a thriller — often involving characters racing against the clock, entering places they mustn’t, or crossing people they shouldn’t. This one is no different: Tori and Lokita work for pennies at an Italian restaurant, singing songs for the customers, then dealing drugs all over the city for the joint’s owner so they can make money to send to Lokita’s family back home and to the smugglers that brought them here. These two kids are surrounded by cruelty, indifference, and suspicion, but their relationship also allows us to feel some hope. It also means that the film becomes ulcer-inducingly unbearable once things truly start to spin out of control. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of Tori and Lokita.

Walk Up

This cleverly constructed comedy from Hong Sang-soo takes place entirely in a small Seoul apartment building that provides not just the setting for the movie, but its structure. Byung-soo (Hae-hyo Kwon) is an acclaimed filmmaker paying a visit to the building’s owner, an old friend named Ms. Kim (Lee Hye-young) who soon realizes he has ulterior motives. But what follows are sly episodes that take Byung-soo to each level of the building in what can be seen as glimpses of his future romantic and professional disappointments, or as forward-looking fantasies about his life as he gradually loses the status that’s key to his identity. —A.W.

Read Alison Willmore’s review of Walk Up.

Rye Lane

The romantic comedy isn’t dead, it’s strolling around South London in the company of Dom (David Jonsson) and Yas (Vivian Oparah), a pair of charming 20-somethings who end up spending the day together after a less than auspicious meet cute in the bathroom of an art gallery. Both are getting over breakups, and the joy of Raine Allen-Miller’s movie comes from the dawning realization in each, over teasing banter and some mini-adventures along the way, that they might finally be ready to open their hearts again. —A.W.

Read Alison Willmore’s review of Rye Lane.

Stonewalling

Ji Huang and Ryûji Otsuka’s bleakly funny film has you aching for its 20-year-old protagonist Lynn (Honggui Yao) as much as you also feel exasperated with her naïveté. Lynn, who’s studying to be a flight attendant, seems forever a passenger in her own life, but when she finds out she’s pregnant by her self-involved boyfriend, she opts to keep the baby in a scheme to help her mother, one of the few firm decisions we see her make. In Stonewalling’s vision of a contemporary China accelerating toward dystopia, this shifts Lynn from being commodified for her beauty to being commodified for the fetus she’s carrying, navigating an increasingly absurd fertility industry that suggests her future prospects are bleak. —A.W.

Creed III

Congrats to Michael B. Jordan for turning a creaky boxing franchise into something deliciously close to shonen anime. —A.W.

Read Alison Willmore’s review of Creed III.

Operation Fortune: Ruse De Guerre

Guy Ritchie movies should theoretically be romps, but an overbearing fussiness threatens to kneecap many of them at every turn. Here then is something genuinely charming and light-footed: An espionage comedy-thriller in which a British superspy (Jason Statham) with a fondness for the finer things in life puts together a team to infiltrate the world of a playboy billionaire arms dealer (Hugh Grant), who just happens to be obsessed with the work of an action-movie star (Josh Hartnett), who in turn also gets roped into the elaborate scheme. With plenty of action set pieces — shootouts, car chases, and acrobatic beatdowns — you could imagine this as a dry run for a James Bond film, but the humorous banter and the cast (with especially charming turns from Hartnett and Grant) place it firmly in the realm of comedy. Everybody in Operation Fortune — yes, even Guy Ritchie — seems to be having fun. Sometimes, that’s all you need. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of Operation Fortune.

Cocaine Bear

Cocaine Bear is, above all else, a title and a concept, and the movie clearly understands this. Elizabeth Banks’s action-comedy-thriller is loosely based on a 1985 incident when an American black bear ingested a massive amount of cocaine and was found dead soon thereafter. The film concocts a fanciful story — a series of stories, really — out of what might happen if an enormous bear went on a savage, indestructible, coke-fueled rampage through the Georgia woods. It’s part Spielbergian kids’ adventure, part slasher flick, with an ambling, gory insouciance that might have been more off-putting in a movie not called Cocaine Bear. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of Cocaine Bear, Chris Lee’s interview with director Elizabeth Banks, and Derek Lawrence’s interview with star Keri Russell.

Linoleum

Colin West’s gentle sci-fi comedy-drama plays like Interstellar remade by Wes Anderson. Jim Gaffigan gives a warm, charming performance as the host of a children’s science show who loses his job and decides to build a rocket from the remains of one that has crashed in his backyard. Meanwhile, his rebellious teenage daughter begins falling for the new kid at school, who just happens to be the troubled son of the hard-ass, go-getter astronaut who replaced our hero at his job (also played by Gaffigan, now with a sinister mustache). But as the characters’ realities begin to fray, we start to sense that there’s more to this story than what we’re seeing. It’s a moving film about time, ambition, aging, wormholes, and the all-consuming power of love. And the film’s quaint, handmade qualities help make the tears it remorselessly jerks out of you feel like honest ones. —B.E.

Knock at the Cabin

Four strangers (led by a wonderful Dave Bautista) emerge from the woods and present a family — a young girl and her two fathers (Jonathan Groff and Ben Aldridge) — with an impossible choice: They must willingly sacrifice one member in order to avert the apocalypse. The film smoothly moves from the textures of one type of thriller to another, even as the mood remains eerily consistent. A Frankenstein opening soon gives way to a home-invasion picture, then a village-cult horror movie, and finally a disaster flick. Knock at the Cabin is based on Paul Tremblay’s 2018 novel, The Cabin at the End of the World, and the script follows the book pretty closely for the first two-thirds. Both are works of the apocalyptic imagination, but Tremblay’s tale is more insular, working the ambiguity of the situation to explore the characters’ faith and emotional perseverance. Shyamalan, however, understands that there is usually little ambiguity around such horrors in cinema; in 2023, when someone in a movie says the planet is ending, it usually is. Instead, he returns to one of the animating ideas of his early work: a profound grief at the state of the world. The result is the most exhilarating and wounding film the director has made in many, many years. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of Knock at the Cabin.

One Fine Morning

Mia Hansen-Løve makes pictures that amble along with the rhythms of the everyday, about characters who never quite know what to do with themselves when they experience brief moments of happiness. She borrows odds and ends from her own life (and the lives of those around her), and reconfigures them into stories that carry the unnerving echoes of truth. In One Fine Morning, Léa Seydoux plays a widowed single mother whose philosopher father (Pascal Greggory) has been struggling with dementia. While mulling what to do with his rapidly deteriorating condition, Sandra reconnects with an old, married friend (Melvil Poupaud) and begins a heated affair. Suddenly, she finds herself deeply in need of this man’s affections — cherishing her moments with him while trying to hold off the irreparable sadness that seems to surround her. This could have easily become a torrid, tear-jerking melodrama, but Hansen-Løve’s matter-of-fact approach to performance and incident allow the emotions to emerge organically from the unfussy drama onscreen. She reminds us that beauty is often found in the mundane cadences of ordinary life. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of One Fine Morning.

Plane

Plane. —B.E.

Read Bilge Ebiri’s review of Plane.

Saint Omer

Alice Diop’s stunner of a film tucks a whole fraught universe into a courtroom drama. Kayije Kagame plays Rama, an author and professor who attends the trial of Laurence Coly (Guslagie Malanda), a woman who’s been accused of killing her own baby. Rama intends to make Laurence the subject of her next book, but instead, to her fascination and sporadic horror, sees herself in the admitted murderer, especially in their shared experiences as Senegalese immigrants and receptacles of immense parental expectations. —A.W.

Return to Seoul

With his film Return to Seoul, writer-director Davy Chou grounds his story in Park Ji-min’s features and expressions. Her debut performance is so piercing it makes the entire film move like a breathing poem. Park plays Frédérique “Freddie” Benoît, a 25-year-old Korean woman adopted by a white French couple, who has returned to her ancestral home. When she visits an adoption center to find out more about her parents and realizes the organization must formally send requests to her birth mother and father, Freddie tries to remain impenetrable. But cracks in her charismatic façade become undeniable when she travels to meet her father and the family that could have been hers. There are no grand speeches, no sudden or dramatic upheavals, no twinkling score to mawkishly pull at your heartstrings. Return to Seoul carries itself with a gentle forcefulness. Where do Freddie’s wounds begin? Where does the pain of her torn identity end? It is in the grooves of Park’s beauty, the clarity of her emotion, that we come to understand Freddie’s life as a fable written upon sand. —A.J.B.

Read Angelica Jade Bastién’s review of Return to Seoul.

The Quiet Girl

It may not have won the Oscar, but Colm Bairéad’s 1980s drama about a neglected 9-year-old is a delicate marvel. Filmed entirely in Irish — a first for a Best International Film nominee — The Quiet Girl stars newcomer Catherine Clinch as the vulnerable Cáit, who’s sent away for the summer to live on a farm with distant cousin Eibhlín (Carrie Crowley) and her husband Seán (Andrew Bennett). The couple lost their own child years ago, and the film’s subdued pleasures come from the way the visit makes all three of these wounded people open up, with Cáit, pushed to the margins in her crowded home, blossoming under the attention and care she’s been craving all her life. —A.W.