Just as the film Contagion has found a second life with news of the coronavirus outbreak, so too are novels about epidemics popping up on reading lists around the country. With stakes so high, it’s easy to see why novelists find outbreaks of disease so compelling. Here are 20 great fictional takes, ranging from the historical to the futuristic.

From 1665 to 1666, bubonic plague returned to Britain and devastated the city of London — killing roughly one quarter of its population in the span of 18 months. Over 50 years later, Daniel Defoe drew upon historical documents to write a realistic account of the plague’s effects on the city. Defoe’s novel still has the power to unsettle — like when he writes about families forced into quarantine due to an infected family member: “[I]t was generally in such houses that we heard the most dismal shrieks and outcries of the poor people, terrified and even frighted to death by the sight of the condition of their dearest relations, and by the terror of being imprisoned as they were.”

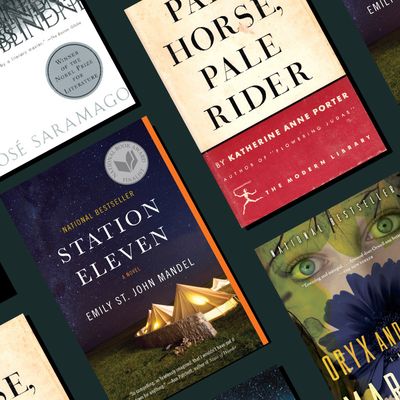

Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider is set around the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 and focuses on a young woman falling in love with a soldier, as both influenza and World War I loom ominously. As novelist Alice McDermott makes clear in her commentary on the novel, it’s a book that hasn’t lost its contemporary resonance.

As befits a novel with the archetypal title The Plague, there are multiple ways one can interpret Camus’s 1947 work. Writing in the Guardian in 2015, journalist and war correspondent Ed Vulliamy contends it can be read in two ways: first, as a metaphor for the horrors of fascism; and second, as an allusion to a cholera epidemic in Algeria in 1849.

A group of scientists deal with an epidemic caused by an extraterrestrial microorganism — one that’s constantly evolving and has no precedent in human history.

In The Stand, the devastation of humanity by a virus named “Captain Trips” is only the beginning of the nightmarish scenario his characters face. It’s a book with transgressive power; as horror writer Grady Hendrix observed, “You can feel the great relish King took in burning it all down in The Stand.”

“Plagues are like imponderable dangers that surprise people,” Gabriel García Márquez told the New York Times in 1988. “They seem to have a quality of destiny.” In the same interview, he spoke of his fondness for Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, and how it was one of the inspirations for this decades-spanning tale of star-crossed lovers, where death is never far from the reader’s mind.

There’s a political urgency to much of Spinrad’s science fiction, and his short novel Journal of the Plague Years is no exception. The novel uses a widespread outbreak of a constantly mutating virus to critique conservative responses to HIV and AIDS in the 1980s. “For twenty years, sex and death were inexorably intertwined,” writes an fictional editor at the beginning of Spinrad’s book — what follows are an arrangement of voices, each struggling with literal questions of life and death.

Ryman’s sprawling, thought-provoking The Child Garden deals with a futuristic society in which viruses are used as a tool to benefit and educate humans. In this world, cancer has been cured but life spans have been reduced as an unexpected consequence. It’s a novel in which concepts of sickness, health, and mortality itself are turned on their heads. It’s also reflective of Ryman’s approach to fiction. In a 2006 interview, he said, “Stories make us sick. Neuroses and psychoses are just stories we tell ourselves and believe.”

Griffith’s award-winning novel uses a futuristic epidemic to address questions of gender and society. It’s set in the future, on a planet where a virus has had a significant impact on the travelers sent from Earth to explore it. Given that she’s based in King County, Washington, Griffith has been offering firsthand commentary and analysis on COVID-19.

“Over time I have realized that the disease comes in spurts,” writes the narrator of Bellatin’s short novel Beauty Salon. It’s set in a world devastated by a pandemic affecting only men, leading to their rapid deaths in the face of governmental inaction. The novel’s narrator runs a beauty salon, which becomes a hospice for those afflicted. In a Words Without Borders review from 2010, Maggie Riggs observed that “what [the narrator] has given to them, and Bellatin to us, is a model for dying, and for living.”

In the Nobel Prize–winning author’s Blindness, a growing number of people within a city find themselves unable to see. The government’s response is heavy-handed and authoritarian. Saramango followed it up years later with another novel, Seeing, which dealt with some of the same themes in a very different way.

Over the course of a few years in the 14th century, the bubonic plague killed millions of people in Europe. Robinson’s alternate history, The Years of Rice and Salt, is set in a world that one character describes as “a mutation of the plague, so strong it killed off all its hosts and therefore died itself.” All of which is to say that Europe is largely empty for centuries in the world of this novel, causing a very different balance of global power to emerge.

The first volume in her near-future MaddAdam trilogy describes a world devastated by the effects of genetic engineering, including a plague that has wiped out much of humanity. As with much of Atwood’s speculative fiction, it feels eerily prescient regarding events that took place after its 2003 publication — a cautionary tale about the unexpected and terrible places technology could take us all.

Adrian’s fiction blends his own career in medicine alongside the mythological and fantastical. In his second novel, The Children’s Hospital, a plague called the Botch emerges after a series of events, some apocalyptic, some miraculous. As Myla Goldberg observed in her review of the novel for the New York Times, Adrian “wants to know why people die, what meaning can be divined from their lives and their ends, and whether anything lies beyond. ”

Herrera’s fiction is often set near the border between the United States and Mexico. The Transmigration of Bodies follows a familiar noir scenario — two crime families at war in a single town, during the aftereffects of a deadly plague.

Much of Mandel’s acclaimed novel is set in the wake of a devastating strain of the flu, which kills 99 percent of humanity. The book’s structure juxtaposes scenes of survivors of the epidemic with the sudden end of the world as we know it, as the Georgian flu wreaks havoc. Mandel’s story is an ultimately hopeful one, focusing on the ways art endures.

Find Me is set against the backdrop of an epidemic that erases the memories of those infected — where the search for a cure might be even more harrowing than the disease.

Ma describes a fictional epidemic that taps into anxieties about both pandemics and nostalgia. Shen Fever, you see, has a way of making you repeat old routines endlessly, right up until the point of death. It’s a resonant metaphor for the way the past can burden us.

The plague here takes a more surreal tone. Those who are infected first discover they cast no shadow; once that’s occurred, their memories begin to vanish.

The Old Drift covers over a century of history in Zambia, beginning in the colonial era and ending in the near future. But it’s when the narrative turns to the effect of AIDS on the country that the book takes an emotionally wrenching turn. She drew on direct knowledge: “A whole generation of Zambians were wiped out by HIV/AIDS, and I lost a lot of family members, mostly cousins who were much older than me,” Serpell told the Los Angeles Review of Books last year.

Every editorial product is independently selected. If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.