“You’ll be fine.”

That was the assurance Jimmy gave Howard mere minutes before Howard was shot in the head. But setting aside this tragic piece of timing, when two major subplots suddenly collided, Jimmy was essentially right, and even Howard had to agree with him. Yes, he’s suffered serious professional embarrassment due to Kim and Jimmy’s scheming. And, of course, he’s angry and hurt about the months of planning that went into a prank designed to humiliate him for sport — first through a series of feints suggesting he was a cocaine fiend and then a grand finale in the HHM conference room, which upended his plans for the Sandpiper case. But still, he would dust himself off and survive. He would be fine.

What happens in this devastating episode of Better Call Saul is really as simple as the phrase suggested by its title: “It’s all fun and games until someone gets hurt.” Last week, Kim and Jimmy were too engrossed in their immediate survival to think about how their lives would change when they returned to whatever “normal” looked like. There would be a reckoning of some sort, given the violence that had come to their doorstep, but they would each have to imagine what the future of their careers and marriage would be. One thing seemed immediately certain: The “fun and games” part of their relationship — the kinky thrill they got in orchestrating scams in the name of justice — was over. The question then becomes, “What next?”

Let’s table the answer for now, because most of the episode is about our main characters coming to terms with the deaths of Lalo and Howard and seeking some form of absolution. In an extraordinary scene, Mike visits Nacho’s father to tell him about his son’s death face to face and offer some kind words about the type of person he was. It should be said that Mike didn’t have to do that, and he’s compelled by a sense of decency and honor that isn’t shared by many of the people in his world. In fact, he lobbied ceaselessly on Nacho’s behalf for Gus to do right by him, and he did everything he could to help Nacho gets through what turned out to be an impossible situation. Visiting Nacho’s dad is a final act of generosity on his part: He can reassure the man that his son felt no pain and that he had “a good heart,” not like others in the business. When Mike adds that “justice” will be coming for the Salamancas for what they did to his son, however, Nacho’s dad is having none of it: “What you talk about is not justice. What you talk of is revenge. My boy is gone … You gangsters and your ‘justice.’ You’re all the same.”

That last part stings, but it’s an important reminder of who Mike is. We’re so accustomed to admiring him for his cool professionalism, his code of honor, and his commitment to his daughter-in-law and granddaughter that we can forget the essential fact that he’s a fixer for a murderous drug dealer. He’s so fully immersed in this cutthroat world of exploitation and death that he’s lost touch with how ordinary people process loss or seek justice. Nacho was murdered. That’s the type of loss that Mike witnesses — or straight-up administers — all the time, but this man is dealing with the death of his child. That’s a kind of pain that Mike cannot answer for, other than to promise more violence. His goodness is only relative to the vipers in his sphere. To an upstanding, hard-working citizen like Nacho’s dad, he’s not much better than a common gangster.

Within that world, however, there’s some flexibility. By all rights, Gus should end his meeting with Don Eladio, Don Bolsa, Hector Salamanca, and the Cousins with a bullet in his temple. Hector has come forward with the accusation that Gus was responsible for the raid on Lalo’s compound in Mexico and his subsequent “disappearance” in the States, and he has some credibility, despite all the work put into tagging Peruvians for the job. Eladio chooses to send poor Hector off to bed, dinging his bell in protest. And it seems likely that he believes Hector is right but respects Gus’s power move enough to allow the Peruvians to be a plausible scapegoat. Eladio knows that Gus hates him over what happened to Gus’s partner, but an earner is an earner. With the Lalo matter settled, it’s time to go back to making money.

For Kim and Jimmy, the guilt they feel walking into a wake for Howard at HHM is overwhelming, like entering the lion’s den. They are responsible for what happened, however circumstantially, and yet they have to persist with the shameful fiction that they’ve invented about him. The notion of Howard as an addict was set to expire like a carton of milk until his death required the same bogus narrative that was used to muck up the Sandpiper deal. They’re unmasked, improbably, by Howard’s widow, Cheryl, who’d been seeking a divorce and who was last seen callously dumping his meticulously crafted cappuccino into a travel mug. After Jimmy gives an unconvincing performance on their behalf, it’s up to Kim to step forward with a better lie, aimed at convincing less Cheryl than Cliff, who’s standing at her side. Cliff has witnessed Howard’s raging fake drug habit on multiple occasions, after all. Now Cheryl gets to be snagged by the same prank.

That’s the final straw for Kim, though it seems likely she would have come to the same conclusion about her life with Jimmy regardless. The brilliant opening montage, set to Harry Nilsson’s “Perfect Day,” chronicles Kim and Jimmy going about their business just as Mike instructed as if the waking nightmare they’d just experienced hadn’t happened. And they’re able to do it, too, as Mike and his crew meticulously wipe away every last speck of evidence from their apartment. In an episode full of unsustainable fictions, this is the most tantalizing one: that nothing ever happened. No one will come for Kim and Jimmy — it’s Mike’s job to ensure that. But can they live with it? Can they return to a spotless apartment and pretend the floor wasn’t once pooled with blood?

The look on Kim’s face in that montage says “no.” As does the look on her face in bed later that night, when Jimmy assures her that a day will come when they don’t think about what happened and know that they can forget. But it’s more than the guilt and horror that prompts Kim to leave everything behind instantly — the law, the apartment, her marriage. She comes to the hard conclusion that she and Jimmy are good with each other but a “poison” for the world, and all the “fun” they have running schemes — even schemes that have achieved a roundabout form of justice — has led to a result that’s not justifiable. In the end, she doesn’t have Jimmy’s moral flexibility, much less his initiative to deposit it in an entirely new persona named Saul Goodman.

The cut from Kim’s decision to leave to Jimmy waking up next to a prostitute in his gaudy, nouveau riche mansion at some unspecified point in the future is brilliant. We don’t need to fill in the steps that got Jimmy from here to there because Jimmy McGill moved out right along with Kim. He’s Saul Goodman 24/7 now.

Burners

• For all the fretting over Kim’s fate over multiple seasons of the show, it never felt likely that she would be killed off, as many seemed to fear. Obviously there are a few episodes left and anything could happen, but her relationship with Jimmy, along with her own fascinating impulses, is more important to the show than her intersection with Albuquerque’s criminal element. This was the truest fate, and the Emmy-nominated (finally!) Rhea Seehorn nailed the moment as usual.

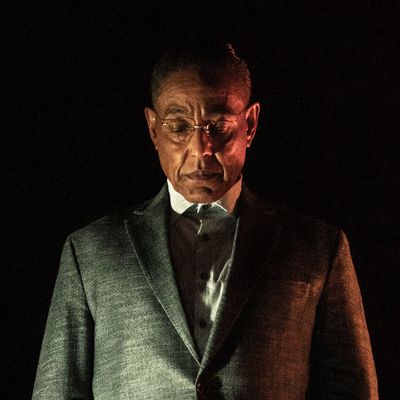

• As a fan of the groundbreaking show Homicide: Life on the Streets (and The Shield and Dollhouse), I thought it was a treat to see Reed Diamond turn up for a one-scene wonder as the sommelier who flirts with Gus at the restaurant. It’s an important character moment for Gus, who can finally open up the shutters at his home and presumably lead a freer life, but ultimately decides that he must continue to do this alone. Giancarlo Esposito’s darkening expression is something to behold.

• Speaking of veteran actors, that’s Arye Gross as the judge who’s shocked by Kim’s late-breaking motion to remove herself as her client’s attorney. Gross has been bopping around film and television since the mid-1980s, and there was a brief moment when he stepped up as a leading man in comedies. Unfortunately, those comedies were the notorious 1986 film Soul Man, in which C. Thomas Howell dons blackface to get a college scholarship, and 1989’s The Experts, which is generally considered one of the low points in John Travolta’s career. Gross has acquitted himself well since.

• “I love you.” “I love you too. But so what?”

• UPDATE: In the original post, I incorrectly asserted that Mike could not understand the pain Nacho’s father is feeling over the loss of his son. This is not true. Mike also lost his son, who was murdered by corrupt cops. I regret my lapse of memory.