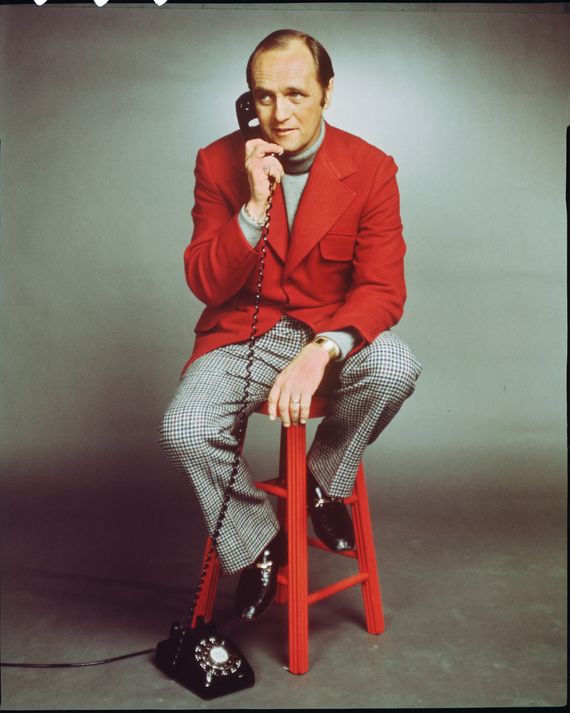

Bob Newhart, who died yesterday at 94, was known as the star of The Bob Newhart Show (the one where he played a psychiatrist) and its equally popular follow-up Newhart (where he ran a Vermont bed-and-breakfast) as well as guest appearances stretching from The Ed Sullivan Show and The Tonight Show (he filled in for Johnny Carson 87 times) through The Rescuers, The Simpsons, In & Out, Elf, Murphy Brown, and NCIS. He almost always played a variation on the established Bob Newhart persona: a mild-mannered, mild-looking, dryly funny guy surrounded by, and reacting to, people far weirder than himself. None of this would’ve happened without Newhart’s foundational skill: an impeccable ability to be the funny one and the straight man at the same time, often while performing a phone conversation. The Newhart character onstage and onscreen was by turns befuddled, lightly annoyed, and (especially) a sane man required to deal with a ridiculous situation, trying to keep it together and mostly, but not completely, succeeding. Shelley Berman specialized in the half-heard phone call and got to the idea before Newhart, but his manner was spikier and more irritable, both onstage and off, and his career soon plateaued; Newhart’s hesitant, deadpan approach was easier to like and more durable and (it eventually turned out) adaptable. The laughter often came as the audience mentally filled in the other half of the dialogue, which was sometimes obvious and unsaid but usually redelivered by Newhart’s character, as if for emphasis.

Here’s a representative clip from the 1967 Christmas episode of The Dean Martin Show, in which Newhart does a routine about a bomb-squad officer taking a call from an underling who’s found an unexploded shell. “What kind of shell?” the officer asks. “What’s the matter, doesn’t it make the sound of the ocean when you hold it up to your ear, Willard?” The conversation escalates and escalates as it becomes clear that the bomb is active; now we’re watching an anxious, somewhat milquetoast guy (Newhart excelled at playing such men) caught up in a bizarre situation and reacting with unease, incredulity, confusion, exasperation, and inappropriate excitement. “You know how powerful that thing is, Willard?” the bomb master asks, grinning. “Six city blocks, Willard!”

“You play these notes so brilliantly,” Newhart’s friend Conan O’Brien told him during a podcast interview, “and with such a quiet ear. It sets you apart from everybody else.”

This mode of comedy originated in 1958 when Newhart was working in Chicago as an accountant for Glidden Paint. Newhart told the A.V. Club in 2012 that “to break up the monotony of accounting,” he would call his friend Ed Gallagher, a junior copywriter at Chicago ad agency who was in a local theater troupe with Newhart, and “we would improvise over the phone. I called him one time and I said, [in nasally voice] ‘Mr. Smithers? Yeah, this is Bob at the yeast factory, and we have a fire here, sir. The fire company, they’re pouring water on it … Mr. Smithers, I’m gonna have to run up to the second floor.” Their comedy, Newhart admitted, was not just influenced by the popular radio duo Bob and Ray; “It was a rip-off of Bob and Ray.”

Newhart and Gallagher recorded their best sketches to vinyl and sent sample records to radio stations across the United States, hoping to place the routines as syndicated material. A few bit, but they weren’t making any money, and Gallagher got a copywriting job at BBDO in New York.

Newhart, left as a solo act, decided to write phone calls in which half the duo was unseen and unheard. “I was faced with finding another partner or doing it on my own, and decided to do it on my own. Some would say I didn’t really do it on my own. There was always that other person; it’s just that he was unheard. He was Abe Lincoln, or he was my boss at the Empire State Building and I was a guard there.”

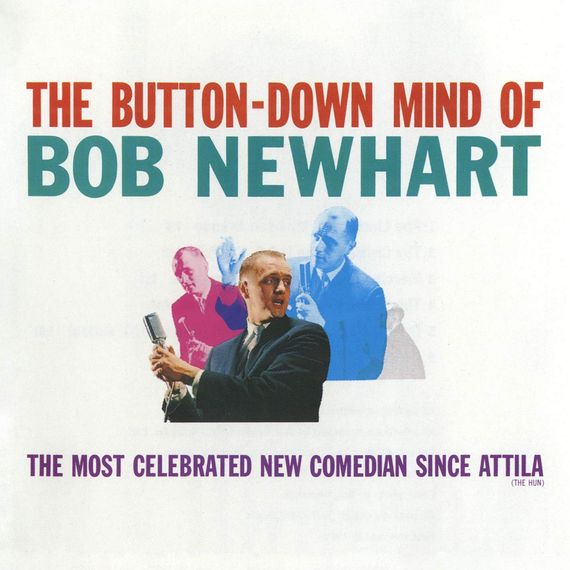

Those routines got him signed to Warner Records, and he began expanding and polishing them in nightclub appearances. Then in 1960, Warner released his first stand-up album, The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart, recorded at a nightclub in Houston. (It’s subtitled The Most Celebrated New Comedian Since Attila the Hun.) Newhart played an increasingly terrified driving instructor, the TV director doing a run-of-show for Soviet premier Khrushchev’s first trip to the United States, and a New York ad man advising Abraham Lincoln not to rewrite the Gettysburg Address. “You changed ‘four score and seven’ to ‘eighty-seven’? Abe, I understand they mean the same thing … It’s kind of like Mark Antony saying, ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen, I got something I wanna tell ya.”

To everyone’s shock, including Newhart’s, it was an absolute smash hit. The Button-Down Mind became the first comedy album to reach No. 1 on what would later be called the Billboard 200 chart. It was hard for Americans to move through life in the early 1960s without hearing it. For the rest of his life, Newhart’s fans would come up to him and reproduce chunks of it. It figures into a first-season episode of Mad Men (“New Amsterdam”) as well as the pilot episode of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel (which is set in 1958, two years before the record was released; oops). The album stayed at the top of the charts for 14 weeks and won Newhart two Grammys, both unprecedented for a comedian: Best New Artist and Album of the Year. No other comic after Newhart won Best New Artist, and only one other comedy record (The First Family, Vaughn Meader’s gentle Kennedy spoof) won Album of the Year. Newhart recorded six more comedy albums in the ’60s. Most had “Button-Down” in the title. All were hits.

He was in demand as a comedy, talk-show, and variety-show guest, and the format he’d perfected in nightclubs adapted well to TV sketch and stand-up spots. On The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, he played an air-traffic controller telling a passenger how to land a jet. (“No, no, it’s easy. You just disengage your automatic pilot. It’s a lever over your head to the right. Not all the way to the right. You just emptied the washroom.”) He booked acting gigs as well, even though he was a tough fit for any part where he wasn’t playing That Newhart Guy (notable roles included the ad executive in Norman Lear’s Cold Turkey who promises $25 million to any small town whose population can stop smoking for a month, and Major Major in the 1970 Mike Nichols adaptation of Catch-22).

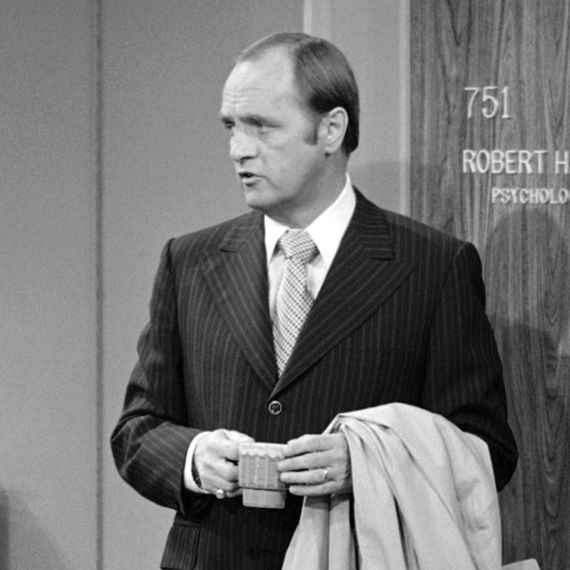

Then came The Bob Newhart Show. “As we were working on the concept for The Bob Newhart Show, they were saying that Bob is a good listener based on the telephone routine, so let’s find a profession where he is a listener,” Newhart told National Public Radio. Bob Hartley, a, um, buttoned-down psychologist, was of course the ideal role: not only a listener but one who had to keep his cool while talking to eccentrics. Suzanne Pleshette played Bob’s sardonic and knowing wife Emily, with I Dream of Jeannie co-star Bill Daily constantly intruding as their goofball neighbor, Howard Borden. An ever-growing cast of recurring and guest characters filed through the Rimpau Medical Arts Center where Bob kept his office-treated patients, including Peter Bonerz as Bob’s floormate, orthodontist Jerry Robinson, and Marcia Wallace (later Mrs. Krabappel of The Simpsons) as receptionist Carol Kester, the first line of defense against Jerry’s manic peppiness.

The excellent joke-writing and clever adaptation of Newhart’s persona aside, The Bob Newhart Show also distinguished by its matter-of-fact grown-up milieu (the Hartleys had no children) and its portrait of a healthy marriage in which spouses ribbed each other and muddled through disputes and misunderstandings but were never less than loving and appreciative. Set in Newhart’s beloved Chicago, The Bob Newhart Show was co-created by Dave Davis and Lorenzo Music (who also supplied the voice of Carlton the Doorman on Rhoda and the first voice of Garfield the Cat). Music, who once said Newhart was a star because he “listened funny,” was also the co-composer with his wife, Henrietta, of the show’s opening theme, “Home to Emily,” a big-band jazz scorcher. The piece’s warm and elegant middle is a tribute to Pleshette and Newhart’s chemistry. They were the most believably in-love-with-each-other TV couple since Dick Van Dyke and Mary Tyler Moore on The Dick Van Dyke Show.

The Bob Newhart Show was produced by Moore’s company MTM and followed The Mary Tyler Moore Show on CBS’s Saturday night schedule, a solid ratings lead-in. For a brief time, the two programs formed the middle hour of the greatest three-hour comedy lineup in American TV history, kicking off with All in the Family and M*A*S*H and finishing with The Carol Burnett Show. The Bob Newhart Show also became a talent farm for future MTM stars, as Bob’s patients included Howard Hesseman (WKRP in Cincinnati) and Daniel J. Travanti and Michael Conrad (Hill Street Blues). The Bob Newhart Show ran from 1972 to ’78 and became one of the most durable of sitcoms, still airing in reruns today, inspiring subsequent series to borrow its characters for meta cameos. Newhart reprised Bob Hartley on several other programs, including Murphy Brown. In the opening minutes of Newhart’s Off the Record — a 1992 stand-up special that marked his return to the stage — he tells the crowd, “When I did my first show, The Bob Newhart Show, the one question I was asked more than any other was, ‘Did you do anything before this?’”

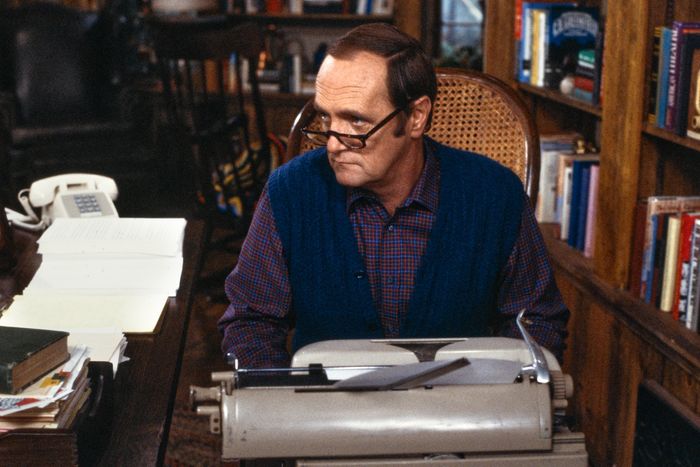

His next sitcom, Newhart (1982 through 1990), beat the odds and pressed the reset button. This time, he played a travel writer named Dick Loudon who’s moved from New York City to Vermont with his wife, Joanna (Mary Frann), to run a bed-and-breakfast in a town with as many weirdos as Bob Hartley’s Chicago had, though none of them had any idea they should be in therapy. Created by Barry Kemp, a Taxi writer who also created Coach, Newhart was another smartly written and endearing half-hour comedy. At its best, it had the winsome oddness of a Roz Chast New Yorker cartoon. The brilliant supporting cast (including Tom Poston as the game but easily flustered handyman George Utley and the trio of William Sanderson, Tony Papenfuss, and John Voldstad as woodsmen brothers Larry, Darryl, and Darryl). It’s sharp and funny, if a more conventional sitcom than Newhart’s first — the kind of pretty good show that, had it been his only one, would’ve been his first-line-in-the-obituary achievement. (A third sitcom, Bob, also aired in 1992 and ’93, offering an older and somewhat crabbier version of Newhart’s usual character. It never really found an audience and was heavily reworked between its two seasons before being canceled. Newhart once joked that he’d run out of title variations after that, and that any future show of his would have to be called The.)

Newhart’s final scene all but admitted that the show was only his second-best, but it was a comparison Newhart was surely glad to invite because it came from such a great idea: The entire series was revealed to have been contained within a dream of Bob Hartley, who wakes up with Emily in the bedroom set from The Bob Newhart Show. The inspiration has been credited to various Newhart writers and producers and also to Newhart’s wife, Ginnie. Though intended as a spoof of “it was all a dream” twists on such shows as Dallas and St. Elsewhere, the Newhart ending took on a life of its own. It caused such a sensation that it was referenced and parodied on other programs, including a 1991 The Bob Newhart Show reunion special (Bill Daily says he’s had recurring dreams of living as an astronaut in Florida, referencing his early role on I Dream of Jeannie, then runs into Larry, Darryl, and Darryl in the elevator) and Saturday Night Live (Newhart wakes up with Pleshette again and says he had a dream about hosting SNL, and she asks, “Is that still on?”). Breaking Bad even shot a jokey “alternate ending,” released online, in which the crime drama turned out to have been a nightmare of Bryan Cranston’s other famous TV character, Malcolm in the Middle’s dad Hal (who wakes up beside Cranston’s Malcolm co-star Jane Kaczmarek).

Newhart later told the New York Times that some fans disliked the ending because it meant “they devoted eight years of their life” to a set of characters only to learn that “none of them existed …” When asked for his response to their complaints, “Newhart said, simply, ‘Okay.’” He knew what worked, and what, especially, worked for him. “Larry Gelbart said that comedy is just looking at life through a different lens,” Newhart told Larry King. “I guess I just always had that different lens.”