It’s late 1997. Seth Meyers is not yet Seth Meyers, but you can see the outlines of him in the skinny 23-year-old onstage at a scruffy Amsterdam theater. In a white button-down, dress pants, and a dark tie, with his hair pulled back tightly into a small ponytail, he looks a bit like a high-schooler whose parents made him dress up nice for Dad’s company Christmas party. Two-hundred-odd people are clustered at tables, eating, drinking, chatting, and not quite paying attention as Meyers strides to center stage.

“Thank you for joining us tonight at our new Leidseplein Theater,” he says over the din. “We’ve only been here for a few weeks, and parts of our theater are under construction. So, if you see any exposed, sparking wires, don’t put them in your mouth!”

The line gets a laugh. In the six months Meyers had been working for Boom Chicago, an improv-and-sketch company in Amsterdam with a cast and name transplanted from America, he’d learned to appreciate every one. The summer tourist season is long gone in Amsterdam, so the crowd at the Leidseplein is mostly Dutch. “I’ve never in my life met a Dutch person who has politely laughed at something they didn’t think was funny,” he says, looking back on his years at Boom. “Any laugh you get from a Dutch audience was fully earned and deserved.”

Meyers is one of a cohort of influential comics, writers, and directors who had their first real job in comedy at Boom Chicago. The company was founded in 1993 by Andrew Moskos and Jon “Pep” Rosenfeld, two American guys who had, in Moskos’s words, “rose right to the middle of the Chicago improv scene.” During a hazy interlude in Amsterdam a year earlier, the pair struck on what they called “the best stoner idea ever” and then actually saw it through, opening Amsterdam’s first English-speaking comedy theater. The name was chosen because they wanted something that evoked the same idea in any language (though it turns out Boom actually means “tree” in Dutch) and added the “Chicago” as a nod to their roots.

The theater was a training ground for many hugely successful comedy minds, including Meyers, Jordan Peele, Kay Cannon, Jason Sudeikis, Ike Barinholtz, and Amber Ruffin. But perhaps more impressive is the roll call of comedy lifers who’ve spent time there. Of the 100 or so performers in Boom’s 26-years-and-counting history, six went on to work for Saturday Night Live. Eight worked at MADtv. Boom alums have had a significant hand in many of the shows that defined the past two decades of comedy: 30 Rock, Community, Portlandia, The Office, Veep, Arrested Development, Eastbound & Down, Girls, Broad City, How I Met Your Mother, Inside Amy Schumer, Key & Peele, Parks and Recreation, Drunk History, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, Late Night With Conan O’Brien, Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and Late Night With Seth Meyers.

For sheer volume, places like Second City and the Groundlings — and, later, UCB, which didn’t launch its long-standing Chelsea location until 2003 — may have churned out more future stars, but they’ve sometimes had the feel of calcified, hierarchical institutions full of diligent hopefuls working their way up an organizational food chain. When Boom Chicago came along, it offered a chance to skip the line for talent that might have otherwise been lost in the shuffle. Back in the U.S., you were a waiter who did improv on the side. In Amsterdam, you got to turn your hobby into your job.

The opportunity wasn’t without risk. Amsterdam could feel like an exile from comedy’s power centers, but the very fact that it was a gamble tended to attract the bold and the unconventional. And the trade-off seemed more than fair: Boom gave young, inexperienced performers lots of stage time and an actual — if not particularly sizable — paycheck in an environment where nothing was more important than getting a hard-earned laugh from the audience, no matter what language they spoke or how stoned they might be. It became a magical confluence of competing pressures: a place where sharp comic minds were expected to do their job every single night but also could stretch their imaginations and their horizons without the prying, judgmental eyes of the comedy Establishment on them.

“That experience — getting to improvise five, six nights a week, for three years in Amsterdam — was a grind that taught me a lot about showmanship,” says Peele, who performed with Boom from 2000 to 2002. “That little audience voice in my head, that Boom Chicago gauge of whether something will work, feels like a skill I’ll have with me forever.”

When Moskos and Rosenfeld first arrived in Amsterdam in the summer of 1992, they weren’t looking to start a comedy empire. They were looking to get high. At the time, the two childhood friends were hopscotching through Europe on their way to Greece for a postgraduate summer program. “We were like, ‘Might as well stop in Amsterdam and buy a bunch of hash for the trip,’” Rosenfeld recalls. Once they smoked said hash, they came up with the idea to ditch their jobs back home and open Boom. “The idea even made sense the next day,” says Moskos.

At the time, the two Northwestern grads were nobodies in the Chicago improv scene — Rosenfeld had taken classes at Second City, and they’d both been onstage at ImprovOlympic (later known as iO), but that hardly set them apart from every other 20-something in the city with a liberal-arts degree. That meant moving to a different continent to launch a comedy theater was a considerable leap of faith, if not outright desperation. They wrote to the Amsterdam tourism bureau asking for advice. Moskos laughs recalling the fax they got back. “They said, ‘Your idea will not work. The Dutch don’t want to see a show in English. Tourists don’t want to see a show at all. Think twice about your plans.’” That fax is now framed and hanging on his office wall.

Theaters in Amsterdam mostly shut down during the summer tourist season, but Moskos and Rosenfeld figured they could take advantage of the lull. In May 1993, they returned to the city with three performers from Chicago whom they’d convinced to join them in Boom’s first cast. They enlisted another friend from home, Ken Schaefle, as their third partner and the company’s technical director. For a theater, they rented a cheap space in the back room of a dilapidated salsa bar.

They made the city of Amsterdam their makeshift rehearsal space. “We were rehearsing under viaducts,” says Miriam Tolan, who was part of that first cast and later a correspondent on The Daily Show. “We were always trying to get out of the rain and rehearse. We’d rehearse literally under highways. It was completely bananas.” All five cast members plus Schaefle lived together in a narrow, cramped house in an old part of the city. Schaefle built bunk beds in the kitchen. “Nobody complained about it,” says Tolan. “I lived one floor up and slept on the floor on a mattress that I know was taken from the street.”

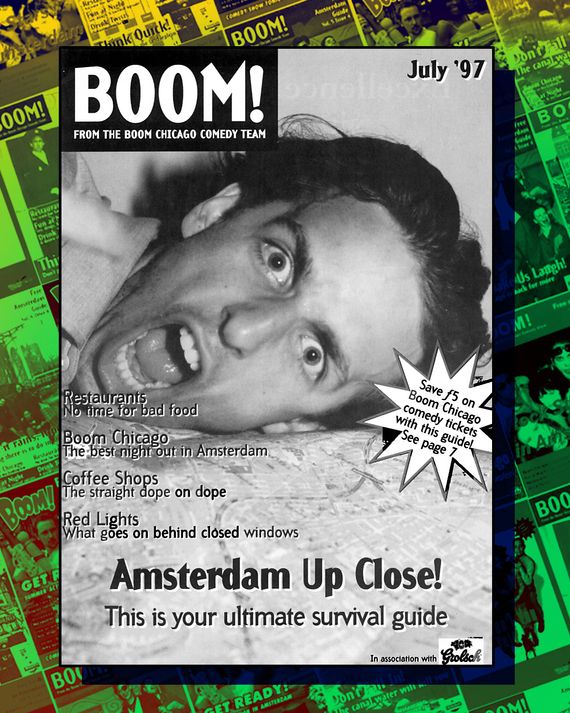

Moskos proved to be a master of street-level marketing. It was his idea to create an irreverent city guide that cast members distributed for free near the train station and other highly trafficked spots. Along with snarky recommendations for things to do in Amsterdam, it directed people to Boom’s shows. “It was pre-internet,” says Moskos. “We were the underground information source.” The Boom Paper, as it was called, was passed from one incoming backpacker to the next. “It worked right from the start, which was a luxurious position to be in,” he says. “We made money in year one.”

When that first summer ended, the cast and crew returned to the U.S. — Moskos went back to working as the assistant manager at an art-house theater, and Rosenfeld waited tables at an Italian restaurant — but plans were already in motion to return the following summer. By year two, Boom had built enough word-of-mouth buzz to relocate from the salsa bar to a bigger, nicer theater called Studio 100.

Efforts to recruit new performers were slow at first — ambitious comics feared losing their place in Chicago’s comedy pecking order. “Anybody who had an agent told them not to go to Amsterdam,” says Moskos. “Because you’re out of sight, out of mind.” But Boom’s pitch was nonetheless enticing: Live in Europe, get paid (a little) to do comedy, see the world. By the third year, Moskos and Rosenfeld no longer had to twist the arms of friends and acquaintances. They held auditions in the off-season and were beginning to suss out the kind of performer who would succeed at Boom.

“You can’t be a mumbly genius,” says Moskos. “You have to be able to own a house.” This ran somewhat counter to much of what was being venerated at places like Second City and iO. “A lot of the Chicago scene, at least then, was about showing your real personality and not raising your voice,” says Rosenfeld. “‘It’s not a show; it’s about truth.’” At Boom, performers weren’t playing to crowds full of fans steeped in the language of comedy and pop culture; in fact, some audience members weren’t even fluent in English. That meant baring your soul was far less important than being able to stand on a stage with good posture, eyes on the audience, project to the last row of the theater, and, you know, make people laugh.

The show was designed to jolt the audience into paying attention. Barinholtz recalls a Friday late-night show soon after he arrived in 1999 that blew him away. “Three or four of the cast members came out, took a few pieces of information from an audience member, and launched into an incredibly impressive improv rap that incorporated this information they’d just learned,” he says. “I was truly like, They’re going to fire me. This is so removed from my skill set. I simply cannot do that.” Peele was similarly impressed when he showed up a year later. “It was a combination of short-form improv and sketch with this really bold punk-rock energy that assaulted the crowd,” he says. A few years later, Boom started putting the cast members through heckling workshops. “We’d treat it like an improv game,” says Heather Anne Campbell, who started a three-year run at Boom in 2003 and later worked at SNL and Key & Peele. “As fast as you can, come up with a joke to put that person in their place.”

In late 1997, the company moved into a large former nightclub in one of the city’s main entertainment districts, a square called the Leidseplein. By the late ’90s, Boom’s reputation was growing in the Chicago improv community. Meyers, future Daily Show and Colbert Report writer-producer Allison Sliverman, and Tami Sagher (30 Rock, Girls, Broad City) were among those who’d been in the cast. “When Seth and I came back [to the States], we just started talking about it to people, saying, ‘This is an awesome experience. You should go audition,’” says Peter Grosz, who arrived at Boom in 1997 and went on to be a writer on The Colbert Report and Late Night With Seth Meyers and played the sleazy lobbyist Sidney Purcell on Veep. “We weren’t quite patient zero, but there was a real word of mouth that started with us and spread to our friends.”

That marked the beginning of something of a golden era for Boom. Between 1997 and 2003, the cast included Meyers, Peele, Barinholtz, Sudeikis, Grosz, Meyers’s brother Josh (who’d eventually star on MADtv), Silverman, Pitch Perfect writer Kay Cannon, Superstore star Colton Dunn, and Liz Cackowski, who’d later write for SNL and Community. “It was this real — holy crap — professional, well-oiled machine full of ridiculously talented people,” says Cannon. “It was just a really special time.”

In Boom’s early years, the crowds were mostly English-speaking tourists. Besides American, Brit, and Irish visitors, a tour company called Kontiki regularly deposited busloads of young Australians on Boom’s doorstep. “They were hammered,” says Grosz. “They’d been high all day or drinking. Sometimes it would be 100 of the 150 people in the audience: Fifty are just watching the show, the other hundred are basically at a bachelor party.” But by 1998, as Boom began to run year-round, the audience had shifted: A majority were now locals. Dutch politics, culture, and norms became frequent targets for jokes. “In Chicago, you can just say funny local references and get big laughs,” says Barinholtz, who spent two years at Boom. “In Amsterdam, they don’t fucking know that American shit, so I had to change who I was as a performer. I had to become really big.”

As Meyers sees it, “it helped you as a performer having to comb out the crutch of pop-culture references. Those were sometimes the easiest laughs you’d get in the States. You had to find more universally human things for people to enjoy.” It helped, he adds, that you also had to slow down. “That’s what you had to do with an audience that was speaking English as a second language,” he says. “Not dumb it down but just be clearer in what you were trying to say.”

Amber Ruffin, who spent the better part of four years at Boom between 2004 and 2011, was later hired by Meyers as a writer on Late Night, and recently launched her own late-night show on Peacock, recalls having to “really learn what faces convey what feelings. Because if you can’t understand me, I want you to be able to understand what my face is saying to you.”

Language wasn’t the only barrier. Audiences weren’t exactly sure what they’d come to see. “A Boom crowd was 70 percent people sitting with their arms crossed going, ‘What’s this?’” says Joe Kelly, who started at Boom in 2001 and later wrote for SNL and How I Met Your Mother. Particularly in Chicago, from where nearly all the early cast originated, audiences were frequently filled with friends and fellow improvisers who might applaud interesting choices and clever moves. “It could be a bit like jazz musicians playing for their friends,” says Grosz. “That got beat out of you at Boom because you don’t get any laughs.”

The Dutch were often quiet during the show, but they let their opinions be known afterward, when performers were contractually bound to hang with the audience members in the bar area. “They were brutally honest,” says Barinholtz. “They’d come up to you like, ‘Your show, it was fine. You were not the funniest one. Your Black friend was very successful.’ It ended up being really helpful because you get uncut truth.”

Navigating the Dutch sense of humor was its own challenge. “They’re not inherently the funniest people,” Barinholtz says. Campbell recalls watching Finding Nemo while she was there and being struck by how the audience reacted. “The opening of the movie was silent, and the first time a fish ran headfirst into coral and bumped his head, the audience roared with laughter — and these weren’t kids,” she explains. “That felt like an illustration of what Dutch people think is funny.” Kelly had a similar experience: “I remember seeing Mean Girls there, and it was doing all right, but then a character falls headfirst into a trash can. That got the biggest laugh of the entire movie.”

Comedy in Amsterdam, the cast members learned, was basically a service-industry job: Rather than hone your own aesthetic, you performed for the crowd. “You develop the ability to be a total ham if you need to be a ham to sell something,” explains Peele. Cackowski, who in addition to her writing has appeared in Forgetting Sarah Marshall and Neighbors, says she got much better at doing characters there. “Physical comedy, voices, big gags — that’s what worked,” she says. “Boom helped us all become character actors.”

Beyond the regular shows in Boom’s home theater, as time went on the cast was also tasked with performing for corporate clients. Each show was custom-tailored to the company footing the bill. There were shows performed in caves, department store windows, German castles, a toga party in Cyprus, the business-class section of a KLM flight from Amsterdam to Chicago, on a train speeding between Holland and Germany. The shows became lucrative for Boom, but they could be tough on the performers. Greg Shapiro, who started at Boom in 1994 and still works at the theater today, recalls a gig for a meeting of NATO defense ministers in 2005. “We had this Osama bin Laden sketch,” he says. “We dress up a dude as Osama, he looks at the audience and says, ‘I will find you and kill you! I will not rest until …’ Then a director comes in and says, ‘Cut, cut! Osama, this is a dating video …’ And that sketch died! NATO wasn’t ready for a bin Laden sketch in 2005.”

“I’ve bombed in the States,” adds Meyers, “but I’ve never bombed harder than I did performing to Dutch and Portuguese construction workers on their lunch break with a 20-minute show about safety. It was an entire audience of people who each had a carton of milk and a hard sausage they were cutting with their own knives.”

Cast members would often get scripts handed to them on the way to these corporate gigs. “We’d have to learn four or five scenes on the ride,” says Dunn. “Before I did that, I wasn’t good at cold-reading scripts out loud. Now, at Superstore, we sometimes don’t get the script until 15 minutes before the table read. Other actors are stressed. I don’t have that anxiety at all. That’s something I built up doing the corporate shows.”

The combination of corporate shows and regular gigs offered young performers lots of stage time. “It’s like an improv Cavern Club for the Beatles,” says Sudeikis, who came to Boom in late 2000. “You get your 10,000 hours. People come back from there better than they left.” Adds Ruffin, “There’s a thing at Boom called ‘cowboying.’ It’s when you’re doing something and don’t know what you’re doing. If you got a script too late or got thrown into a part you’ve never done before, they’d be like, ‘Cowboy it.’ It sounds terrifying, but it’s so good for you.” At Boom, it wasn’t about getting things exactly right onstage as much as it was about handling yourself when things went wrong. Brendan Hunt, who spent roughly five years at Boom starting in 1999 and has since appeared on Key & Peele, Parks and Rec, and Community, says, “If you fuck up at Boom, you’ve got an hour of show left. If that hour goes badly, you’re getting back onstage tomorrow. In Chicago, you might not do another show for a week, so you’re carrying that bad show with you for a week.” Meyers agrees: “None of it felt permanent. If you bombed in Chicago, there were 10 to 20 people you knew who were there, so there would always be the residuals of that bombing. In Amsterdam they were all strangers. When you bombed, it didn’t stay with you.”

Silverman, who was at Boom in 1997 and has since had a distinguished writing and producing career on The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, Late Night With Conan O’Brien, Portlandia, The Office, and Russian Doll, says Boom taught her the value of putting your head down and working. “It’s important as a creative person to develop a way to work at a good level when you’re not inspired,” she says. “We all had to be onstage on days at Boom when we felt we weren’t our best. Part of your job is to know how to make things happen at a moment when you haven’t been visited by genius.”

By the late ’90s, Boom cast members had become local celebrities in Amsterdam. They’d get recognized on the street, hustled to the front of the line outside nightclubs, and even had their own groupie-ish fans. “I especially remember Brendan Hunt, Josh Meyers, Ike — they were just loved,” says Cannon. “Women would crush on them in the audience.”

Random celebrities would sometimes show up: memorably, Ron Jeremy, Jam Master Jay, Sheryl Crow, Pink. One Friday in 2001, Burt Reynolds threatened to knock a drunken Englishman on his ass after he got heckled about his toupee while onstage to play an improv game. In the end, Reynolds calmed down, a brawl was averted, and Peele, Hunt, and the rest of the cast incorporated the whole thing into the improv.

There were, of course, drugs. During the late ’90s and early 2000s, marijuana, ecstasy, and hallucinogenic mushrooms were all either legal, decriminalized, or tolerated in Amsterdam. “In the middle of a nightclub, they’d have booths where you could test to make sure your ecstasy was pure,” says Barinholtz. The Boom crew indulged. “A lot of us were doing ecstasy back then and a lot of us weren’t,” says Hunt. “It wasn’t just us. A lot of the crowd were on ecstasy.”

Cast members occasionally rented a van and visited a Gothic-looking, fairy-tale-themed amusement park called Efteling. “It’d be like, ‘You don’t have to take mushrooms but some people are going to take mushrooms. Let’s all take mushrooms!’” recalls Barinholtz. Around Christmas of 2000, the show’s lighting director, Steven Svymbersky — known as “the Wizard” among the Boom crew — invited Sudeikis, Peele, and Hunt to experience a laser, smoke, and light show at the theater that he’d synced to the Jesus Christ Superstar soundtrack. “It was like noon on a Saturday,” says Sudeikis. “Brendan and I took mushrooms on an empty stomach, and Jordan smoked a bunch of pot.” Sudeikis describes Svymbersky’s subsequent virtuoso performance as “Cirque du Soleil meets Blue Man Group, yet no one was onstage. We were completely out of our minds, maybe more than I’ve ever been in my life.”

Sudeikis’s AppleTV+ series, Ted Lasso, in which he stars as an American football coach who goes to England to coach soccer, grew from conversations he and Hunt had walking the streets of Amsterdam on mushrooms. “Whatever mushrooms make you think and feel, it was evident to me Brendan was beyond smitten with European soccer,” says Sudeikis. “So when NBC Sports came to me with this idea to play that Ted Lasso character, I knew exactly who to get.” Hunt is an executive producer and co-star on the show. Another former Boom mate, Kelly, is a writer.

Living, performing, and partying together in Amsterdam bonded the cast members tightly. “It’s basically like a frat, but without any of the sexual assault,” says Barinholtz. When Cannon cast Barinholtz in Blockers, they had a shorthand she didn’t have with other actors. “I was giving a note to Ike, John Cena, and Leslie Mann, and I just had to start the sentence and Ike totally got it,” she says. “We barely even exchanged words. Leslie was like, ‘What just happened there?’”

Boom did what it could to keep its cast connected to the comedy world back home. In 2001, Peele was part of a stage swap where Boom’s cast performed for a week at Second City. It was there he met Keegan-Michael Key for the first time. “We got to see each other work and hit it off instantly,” says Peele.

Meyers left Boom after the 1998 season but stayed involved from a distance. In addition to making visits back to occasionally direct the show, he continued to write corporate sketches. All the while, he developed a two-person show with fellow ex-Boomer Jill Benjamin, which they toured widely. “When I went back home, the most valuable thing was not wanting to get back in line in Chicago,” he says. “Before we even went back, Jill said, ‘Let’s hit the ground running. Let’s do a show together. We know how to write sketches now, we know how to produce sketches.’ So it wasn’t just that we learned to be better performers. We also learned how to be self-starters, how to package our brand better.” After performing that two-person show in New York in 2001, Meyers was cast on SNL. The news reverberated back in Amsterdam.

According to Moskos, most ambitious Second City performers had always figured the next rung on their career ladder would be in L.A. “When Seth got hired, that changed it all,” he says. “People were like, ‘Boom Chicago could be fun and good for my career.’”

“That was a huge deal for us,” adds Kelly, who was at Boom at the time and was hired to write for SNL two years later. “It was the first person I ever knew personally who got SNL. A bell rung in my head: ‘Oh, I could do this.’”

Today, Boom is a Dutch-American institution. In 2013, the company moved to a new theater, a handsome, 100-year-old redbrick Art Deco palace in an upscale neighborhood in central Amsterdam. They still play to packed houses. (Local pandemic restrictions forced Boom to cease performances through the spring and into the summer. Since July, it’s been holding two shorter shows to smaller audiences, and recently, it had to shutter entirely for a two-week local lockdown that ended November 19.) Boom has added an academy where a new generation of improvisers are being trained. In 2016, Moskos was invited to co-write the Dutch prime minister’s speech for Holland’s first-ever version of the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. The outsiders had become insiders.

Regeneration was always baked into Boom’s DNA. No one expected performers to stay forever (though a couple did). Even two of Boom’s founders eventually grew restless. Schaefle returned to the U.S. in 2005 and became an internal medicine physician. Rosenfeld left in the late ‘90s to write for SNL. When that didn’t work out, he came back. Only Moskos never left. In fact, he married Boom’s first employee, Saskia Maas, who became Boom’s CEO. For most everyone else, Boom was a moment in time. Its continued success depended on turning the cast over every few years.

By the mid-aughts, there was a full-fledged improv boom going on back in America, which transformed Boom’s place in comedy’s farm system from valuable cog to quirky outlier. Plenty of wildly talented writers and performers have continued to emerge from Boom, though none have quite achieved household-name-level breakout success. “In the years since Boom started, improv spread out,” says Meyers. In the mid-’90s, when Boom began, Chicago was the epicenter of the improv and sketch world. If that’s what you wanted to do with your life, that’s where you went. Boom offered another option. “You could argue that it was Chicago, then Amsterdam,” says Meyers. “Now, it’s Chicago, it’s L.A., it’s New York. There are scenes everywhere.” In fact, Boom alums have helped spread the gospel, opening successful comedy theaters in London, Austin, and Pittsburgh. “It was also before the internet,” Meyers continues. “Now, comedians don’t necessarily have to fly to Holland to get people to see them. Boom might’ve had its peak at a time when there were just less places people could thrive.”

In the States, the legacy of Boom’s salad days lives on in writers’ rooms, call sheets, and even in person. Boom’s alumni network keeps in touch via a WhatsApp group where members share memories and photos of their kids. They make periodic trips back to visit. In the summer of 2018, Boom celebrated its 25th anniversary with a giant reunion. “We’ve had about 100 people in Boom over the years, and almost 70 of them” — including Meyers, Barinholtz, Grosz, Ruffin, and Cannon — “came on their own dime to be part of this anniversary show,” says Moskos. The alumni joined the current cast and performed two sold-out shows at the 2,500-seat Royal Carre Theater. “It was a week when the weather was perfect, and we went to all the old places where Boom had theaters and had drinks there,” he says. The alums visited their favorite bars, restaurants, and smoke shops. There was a trip to that creepy amusement park Efteling. Some of the old Boom crew got tattoos to commemorate the experience.

“What those guys created is worth standing up and shouting about because they really shifted things,” says Sudeikis. “It’s no different than what the Compass Players did with Second City or the four original UCB folks did. They did the hell out of it, and it marches on.”