“I guess my question is … can we even talk about the Boss Baby and the other employees of Baby Corp as babies?”

Joshua Poole of UC Riverside, a psychiatry resident, had just wrapped up a 15-minute presentation on The Boss Baby, the 2017 DreamWorks film about a baby blessed with the mind, voice, and corporate fashion sense of Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross. During the Q&A, another resident, Rennie Burke of San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services, wanted to know if Poole had factored in Donald Winnicott’s field-defining research into developmental psychology.

“I was nervous about bringing in Winnicott because he really complicates my argument,” Poole replied warmly, then ventured that his thesis — a deep medical dive into the Boss Baby’s psychotic orientation to the world — still held true. “Winnicott says that we can’t have any understanding of the point of view of the baby, but I’m looking at it from the point of view of the baby.”

This was the unique magic of the first annual Boss Baby symposium. For nearly five hours on the afternoon of January 3, 12 panelists and 75 spectators gathered over Zoom for a day of reckoning with the meme-friendly children’s movie. The symposium was co-organized by two philosophy Ph.D. students, Jaime McCaffrey of the University of Kentucky and Tore Levander of Fordham University, who described the movie as an “interpretive nightmare” to the A.V. Club in 2021. In McCaffrey’s opening remarks, she quipped that the film’s singular vision is “thematically richer than the Bible and more confusing than Ulysses.”

It’s a catchy one-liner, but McCaffrey has a point. The Boss Baby has captured the popular imagination in the form of parade balloons and surreal meet-and-greet footage, but the original film is almost unspeakably crazy. Imagine a world where babies are produced on an assembly line in a supernatural office building called “Baby Corp,” guzzle magic baby formula that endows them with the brains of C-suite adults, and face off with the evil CEO of Puppy Co. (voiced by Steve Buscemi). He is designing a “Forever Puppy” to siphon all of the love in the world away from babies, and he is driven by a thirst for revenge; once upon a time, he was also a Boss Baby, but tragically began aging after developing lactose intolerance. And yet, at the heart of it all, the film tells the story of an ordinary boy learning to live with a new baby brother … who happens to be the titular Boss Baby.

The symposium snowballed organically after McCaffrey and Levander experienced The Boss Baby in theaters during undergrad. “I remember seeing the movie for the first time and thinking, This is so inherently self-contradictory in ways that offer no hope of resolution,” McCaffrey told me over the phone the week after the event. “It just excited me to no end.” As an outlet for this fascination, the pair originally thought of writing papers themselves to present informally to each other, but after posting a call for proposals on the academic database PhilEvents in September 2021, they realized that there was genuine interest in their mission. The scholars who submitted abstracts — mainly humanities graduate students, apart from Poole and Burke — clicked with the symposium’s sense of humor, but they also seemed game to submerge themselves in the movie’s “infantile abyss,” to borrow a phrase from McCaffrey. They even received an email from JP Karliak, the Will Arnett–soundalike voice actor from the Netflix Boss Baby series, asking how he could get involved.

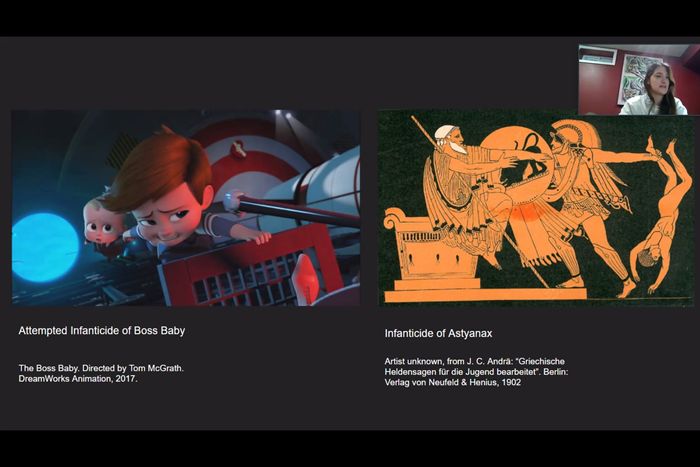

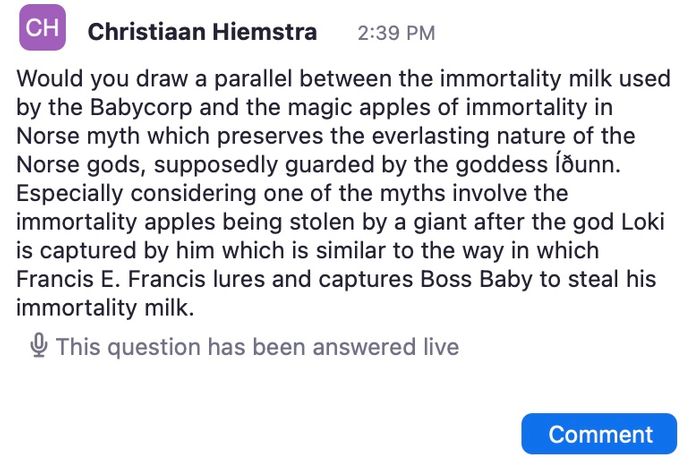

The actual day dug into all things Boss Baby through seven 15-minute talks accompanied by ten-minute Q&As, which can be relived on YouTube. (There was no charge to attend, and all proceeds from the event’s merch store went toward the children’s legal-advocacy charity CASA.) The range of approaches was inspired, and the PowerPoint visuals were breathtaking. Catherine Clement of Northeastern University proposed that the Boss Baby actually has a lot in common with child leaders in ancient mythology, as proven by a slide juxtaposing the “attempted infanticides” of the Boss Baby and Astyanax. Elsewhere, Sam Warren-Miell and Georgie Newson-Errey, English students at the University of Cambridge, took a Marxist angle with their talk, “Lactic Capital in The Boss Baby.” They argued that you drain infant formula of parental warmth when you coldly ration it in break-room water bubblers. “Milk is more of a cipher for capitalism than a commodity,” I jotted dutifully in my notebook. Robin Pawlett-Howell, a philosophy Ph.D. candidate from the University of York, memorably situated The Boss Baby as a work of existentialism, suggesting that this little tyke’s identity as “Boss” prevents him from finding freedom from despair as a “Baby.”

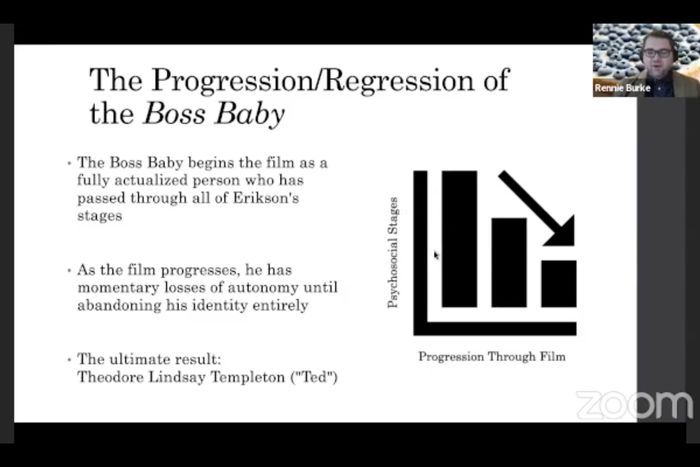

There was something wholesome about this space of academic togetherness — and everyone was really into it. The chat box was popping off with audience questions; one attendee turned on his video to showcase his Boss Baby lunch box to some warm fanfare. Jaws visibly dropped during the final panel as Karliak, taking us behind the scenes of the Netflix series with executive producer Brandon Sawyer, shared that BTS’s Jimin taught himself English by repeatedly watching the film. The Q&As were surprisingly collaborative, each speaker boldly rappelling deeper into the film’s tangled worldview. Can a baby exist outside of the mother/baby dyad? Is Baby Corp a hive mind? Is it possible that this movie completely blasts apart Erik Erikson’s theories of psychosocial development? At the same time, the symposium wasn’t so serious that it became self-parody. It takes a convivial humility to surrender your brain to The Boss Baby for an afternoon, and with a topic this extraordinary — as in, literally outside the realm of the ordinary — several heads are better than one. “There was a moment when Tore said, ‘This isn’t ours anymore — it’s not up to us what this is,’” McCaffrey recalled to me afterward. “This is for other people to cultivate and express this excitement of low-stakes discourse taken to an extreme.”

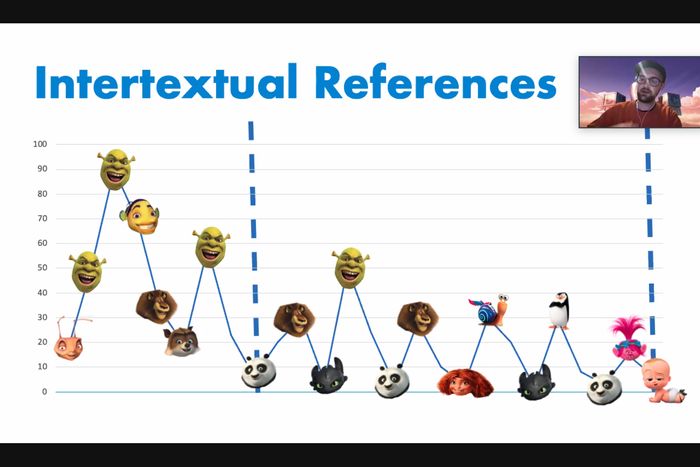

This atmosphere of earnestness might seem odd for a film so tailor-made for shitposting, but that gets at one of the event’s central paradoxes. After posting the conference listing, McCaffrey and Levander were surprised to discover a considerable online response outside of academia. The reactions swirled around the apparent discord between topic and format: Were McCaffrey and Levander really serious, and if they were, what was it possible to glean from a day of Boss Baby scholarship? The clearest precedent for their symposium was actually organized by one of the presenters: Sam Summers, an associate lecturer in animation at the University of Middlesex and the author of a 2020 book about DreamWorks. (His Boss Baby paper, “Cookies Are for Closers,” counted pop-culture references in DreamWorks movies through a line graph punctuated by Shrek heads.) In November 2021, Summers held a media-studies conference about the lasting impact of Shrek, which covered everything from DreamWorks’ rivalry with Disney to the “Shrek Is Love, Shrek Is Life” meme.

Sharing Summers’s mind-expanding vision, the Boss Baby symposium understood that the most bizarre pieces of pop culture can unlock larger truths, if only we set down our self-protective shields of irony and taste. When we see a behemoth balloon of a Boss Baby careening over midtown in an annual parade sponsored by Macy’s, it’s perhaps very easy for us to shut our brains off as a defense mechanism. But what happens when we deliberately clear the space to stop and look, especially at a concept so absurd it almost dares you not to wonder what it all means?

When I asked Levander about the ethos of the conference, he mentioned the influence of queer theorist Jack Halberstam’s theories of low culture. “I like his approach: not trying to look at these texts as if they are serious, but getting beyond needing to be taken seriously in the first place,” Levander reflected, also noting that Halberstam views “thinking” as a form of “playing” — a sandbox-friendly endeavor, to push the baby metaphor to its breaking point. The goal of the symposium was never to get to the bottom of The Boss Baby, but to meet it where it was and honor its enigmas. By rising to that occasion, a ragtag, momentary community formed around what is seemingly the unlikeliest of movies. But even more than that, the conversations challenged the very idea of an “unlikely” conference topic. While discourse is often limited to two extremes — on one end, a jokey tweet about the short king that you might absently scroll by; on the other, “serious” clickbait-friendly writing on The Boss Baby as, let’s say, an allegory for global capitalism — the symposium carved out a space in the middle. Instead of “the movie we need right now,” The Boss Baby is a movie that is right now.

It seems key that the symposium was masterminded by two philosophy students; they weren’t attempting to “reclaim” The Boss Baby as a misunderstood work of art, but to ask questions about its potent cultural magnetism. True to that goal, The Boss Baby ended up less of a film than an eccentric icebreaker, a playful excuse to collaborate across fields — and maybe even critique the psychiatric canon in the process. “Sometimes in academic conferences, people are trying to undermine each other or prove their legitimacy in a sphere,” McCaffrey explained. “The mode that we did this in got rid of that tendency for competition and opened up the space for having fun.”

Encouraged by this first descent into the infantile abyss, McCaffrey and Levander started thinking ahead to a second annual symposium “immediately” after the first one wrapped, although their plans are still abstract. “My MO from the beginning was that we take this as seriously as possible,” McCaffrey added, “and that’s how we make it as funny as possible. Whatever it is, it is.”