Before he made emotionally resonant, character-driven comedy films like The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Knocked Up, and Trainwreck, Judd Apatow wrote for landmark comedy television shows like The Ben Stiller Show, The Larry Sanders Show, and Freaks and Geeks. For his entire professional life, he’s worked for, with, and alongside comedy greats, a behavior that goes back to his days as a talk-show host, interviewing ’80s stand-ups like Jay Leno and Jerry Seinfeld for his high school’s radio station.

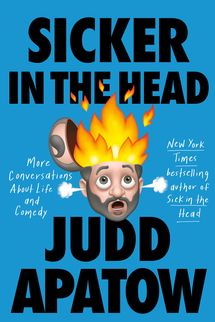

Those interviews, along with some newer ones, were the foundation for Apatow’s 2016 book Sick in the Head: Conversations About Life and Comedy, a collection of insightful conversations about the art and practice of being funny. Six years later comes the sequel, Sicker in the Head: More Conversations About Life and Comedy. While there are a few vintage interviews (like John Candy from 1984), Sicker is comprised primarily of brand-new material compiled over the last few years with legends (John Cleese, Whoopi Goldberg, Margaret Cho, Mort Sahl) and modern humorists excitingly redefining comedy, like Ramy Youssef, Hannah Gadsby, Amber Ruffin, and Bowen Yang, co-host of the Las Culturistas podcast and the person responsible for some of the most memorable and viral Saturday Night Live sketches in years. Here’s Apatow’s chat with Yang from June 2021, excerpted from Sicker in the Head.

Excerpt from 'Sicker in the Head'

Judd: I want to talk about Las Culturistas, the podcast you’re doing with Matt Rogers. How did you two meet?

Bowen: Matt and I met in college. We were both in the closet at NYU, which was just such a funny place to be in the closet, especially circa 2008. I was in the improv group, and he was in the sketch group, and we were both just obsessed with comedy. Recent alums of note from NYU at that point were, like, Donald Glover and D.C. Pierson, and we were just like, “This is the future.” And we put in the work early on and just started to write. My awful snobbery with people who are working in comedy is This can’t be your plan B.

Judd: Sometimes I go to a comedy club and see all these hilarious people onstage, and I wonder if they’ve ever sat down and written a sketch or a screenplay. Or taken the effort to ask themselves, What else can I do with my talent and ideas?

Bowen: I think I heard the legend that you told Bill Hader, maybe during his second season of SNL, that he had to start putting the wheels in motion then so that things will bear fruit further down the line.

Judd: Absolutely. And I did it with Bill, where he worked on a screenplay for us and with some writers from SNL, and we just never cracked it. That screenplay was never made. But we did write a lot together. He said that he was writing like seven screenplays over the course of his time at SNL, of which none were made. But that was all his rehearsal for Barry. He was learning what to do. You have to write, because nobody will be able to write the thing for you that you probably should be doing. It’s daunting to figure out, How does this character or persona work in a full story, in a full movie? That has been the challenge for some SNL people: It’s about figuring out who you are separate from your characters. Once you get past that initial challenge, there’s still the precariousness of the movie business, where you could commit the time to get a movie going, and you still don’t know if someone will want to make it happen.

Bowen: All of that runs counter to the SNL process, where there’s such an efficiency with how things are made. Nothing gets made like that anymore except for summer stock theater. I’m getting a little too used to this. But even now I’m realizing, Oh the credits don’t transfer from SNL, because none of it is made like this. And also, the performance style is you’re pitching to the rafters and you’re screaming and you’re reading off a cue card. That’s not how it works anywhere else.

Judd: It must be an interesting moment for you. When I first started, I felt unrepresented in Hollywood. It was like, Why can’t the goofy, unattractive person ever be the lead? So, in my work over the years, I tried to prove that that was possible, because the non-cool guy as the lead wasn’t available in the culture when I was young. Now our culture has evolved to where people are trying to correct for the fact that performers of color and LGBTQ+ performers have been criminally underrepresented. What does this moment feel like for you?

Bowen: I think, for a long time, Asian people would be used as an existential punch line. Now what’s happening is that, on a collective scale, everyone’s kind of getting on the same page — we’re catching up to some baseline understanding about what the material realities are for Asians in the business. And I don’t know where that’s going yet; I have no foresight into what it will be like. This is all kind of a new thing, and I’m trying not to erase and destroy what people like Margaret Cho have accomplished, or what Alec Mapa has done as a queer Asian comedian. All the groundwork has been laid out by that generation; I’m just benefiting from coming in at the right time. That’s basically how I feel about being at SNL, too. It’s like, Oh I lucked out so, so, so deeply.

Judd: Do you feel like you have a responsibility to use your position?

Bowen: I approach every week at SNL without a care for how something will be received on a social level. The week after the Atlanta shooting in March, I called the one other Asian writer on the show. We got on the phone and were just in a terrible mood, because everything around that story was so bleak. But we asked each other, “How do we want to approach this? Do we address it at all? Do we take a hard left and just not even think about that, and do something that has nothing to do with what happened?” By Saturday, the end result of those conversations was this kind of strident rallying cry, a “Weekend Update” piece that wasn’t particularly funny, but it did bring levity to the situation in whatever way it could. And I had such a weird hangover the next week about it being received well. People were very kind about it, but I was like, I don’t know, I don’t want this to be my role at the show.

Judd: You didn’t want to be like Jon Stewart after 9/11 every week.

Bowen: Even for just one week. Jon Stewart shouldn’t even be in that position, you know?

Judd: The people who are doing political comedy these days have to be the commentators on tragedy and the worst of humanity. It’s such a strange thing that’s happened in comedy, and people are brilliant at it. But I know what you mean. I can’t even imagine being in their shoes, thinking, This shooting just happened, let me try out this piece.

Bowen: Well, the thought was I don’t have all the answers, that I shouldn’t even be doing this. Afterward, I really couldn’t make sense of how I felt about it. Then, two weeks later, I did another “Weekend Update” piece where I was the iceberg who sank the Titanic, and that was just purely me doing my job. It was me co-writing this piece with one of the head writers, Anna Drezen, and creating a fun moment of pure absurdity. Yet the social and political comedy is something that you have to do, especially at a show like SNL, and especially now where there’s a dearth of Asian people who have this big of a platform. So, I don’t bemoan it. It’s just an interesting thing to think about.

Judd: You came to America as a kid, and you didn’t speak English that well because you were still learning the language, but you obviously had a sense of humor. Did you realize at some point, That’s my thing, I’ll be the funny person? Because that’s how I felt as a kid. I was terrible at sports, I didn’t think I was as attractive as the people around me — I guess making people laugh is my thing, because no one else is trying to do it. Was it similar for you?

Bowen: It was exactly like you’re describing it, where I realized, Humor can be my thing. I would come into school on Mondays and ask everyone, “Did you guys watch SNL or MADtv from Saturday?” And some people would be like, “Yeah.” Most kids would be like, “No, what are you talking about? My parents don’t let me watch that yet.” I had these immigrant parents who had no idea what the programming was. So, beyond it being my identity where I was funny and goofy, there was also this extra layer on top where it’ll be my thing to nerd out on comedy, too, which at that age just meant watching SNL every week. That became the keystone for my identity early on, and then I built concentric circles from there.

Judd: As you were watching SNL as a kid, did you ever look at the cast and think, I’m going to be on there someday?

Bowen: I have to be very honest with myself and say I never specifically said the words, “I will be on SNL someday.” But I did have this feeling that it would work out somehow.

Judd: If you have that confidence and drive, then you also know that you need to be ahead of the curve. You know you need to work harder than everybody to realize that dream.

Bowen: Totally. My little secret pet peeve now is the people who are getting into comedy as a fallback. People who were musical-theater majors who didn’t want to audition and didn’t want to do Broadway because that is a whole crazy world of its own. There are those sorts of people who go, Well, I’ll just do comedy instead. And I’m like, “Uh, it doesn’t work like that.” I put forward this crazy purity test for those people, where I was like, “No, you didn’t write down who the writers were on this one episode of The Office as it was airing.” I just got so snobbish about that, and I need to unlearn that now, because I can’t put those gates up for other people who want to get into it through their own means, through their own journey.

Judd: When you went to college, was it your family’s dream that you would go into comedy?

Bowen: No.

Judd: Did your parents see this career as an option for you at all, even if they didn’t love it for you at first? You did premed for a bit. Did you eventually open up to them and say, “I’d rather do stand-up?”

Bowen: My parents could tell that I took comedy seriously even when I was in high school. It was a very big thing for me as a 15-year-old to be a part of this short-form improv group in high school. I thought it was the best thing in the world. I would go downtown every week on Mondays, perform with a bunch of 30-year-olds, and think, This is the thing that I enjoy the most. And my parents could tell I was enjoying it too much. And they had tried to be like —

Judd: “Don’t have joy.”

Bowen: Not even that. I had expressed many times before that I wanted to be an actor someday. And my parents were like, “Well, Bowen, that’s really hard, because there aren’t a lot of Asian ones, and that world is full of rejection.” They weren’t even being domineering; they were just being protective. It was their version of loving me. But when it came time for me to decide on a college, I would visit these campuses and ask them, “Can you tell me about your sketch team here?” That’s essentially what I based my whole college decision on, and I ended up at NYU. I knew all of the people’s names in the improv group by the April before I matriculated. And then I was just obsessed. Everyone around me knew this is what I wanted to do. But I had to take cover behind the premed thing — and it’s so ironic that I was such a jerk about being a purist in terms of pursuing comedy, because my backup plan was medicine.

Judd: You just want to yell at all the other people who are being distracted.

Bowen: My distraction was academics. The thing that got me out of bed every morning was the excitement of seeing everyone in my troupe later that day, and that we would run sets, and do this and that. That improv group was my life.

Judd: Did it make your grades better or worse?

Bowen: Worse, oh worse.

Judd: You would have been a terrible, distracted doctor. When did you stop doing premed?

Bowen: I graduated with my degree, and I had my applications in for medical school. And I was taking my MCAT for the second time, and there was the short-answer portion. When I got to that, I remembered the Steve Carell interview where he said that he was thinking of applying to law school after things weren’t working out for him acting-wise or comedy-wise, but then he got to the essay portion of the LSAT, and he realized then that he couldn’t do it. He couldn’t follow through on this law-school thing. And then, at that moment, I had this out-of-body experience, thinking about Steve Carell, and zoomed back down to me, and it was just like, Oh, this is what’s happening to me right now. I can’t do this. I voided my score, left the testing center, and called my parents. I was like, “I don’t think I can go to med school. I’ll figure out how to stay in the city and live in the city and work in the city and make money, but med school isn’t going to happen.” And they were very confused. To their credit, they gave me a shot to figure it out within two years.

Judd: That’s a big biopic moment, walking out of the testing center in protest. Isn’t it funny that you have to take it that far, till your entire mind and body break down in the middle of the test. Why do you think your parents gave you a chance to figure things out after that?

Bowen: The Big Sick was the first time that we watched a movie that helped my parents understand what I was doing, because all the scenes where he’s doing stand-up, I’m like, “That’s what I’m trying to do, Mom and Dad.” And they were like, “That’s interesting,” and that was a little proof of concept for them. So, I do my best to not retroactively make my parents out to be people who never rooted for me or who counted on me to fail.

Judd: Did they find you funny, though?

Bowen: No, there’s just a big cultural difference between being funny at school with a bunch of kids who speak English and then going home to your parents, who grew up in Communist China. Humor can be culturally specific, and I wasn’t nimble enough to pivot between those two worlds. So, I would come home [and] just be this shy, boring kid.

Judd: When was the moment when you would say, “Come to the improv show”?

Bowen: It was in high school, and I don’t know if it helped or hurt my case. Because they went, and they didn’t get it. They were like, “What is this? We don’t understand.” Then, at one point during college, they came to see one of my sketch shows at [University of California, Berkeley], and they were like, “We didn’t like that. That’s not for us.”

Judd: They were just honest.

Bowen: They just said, “What are you doing?” And to be fair, I would have rated it as, like, a “six” of a show. It wasn’t until Matt and I did this quick little bit on Fallon. My mom went into work the next day, and her co-workers were like, “Oh my God, aren’t you so proud of Bowen for being on TV last night?” It took other people to mirror it to her that her son was doing well. Then she was like, “Okay, maybe this will work out.”

Judd: For me, my dream to get into comedy wasn’t questioned. My family was like, “Yeah, go to that as a career.” Even though I had no confidence in anything else in life, I had a delusional confidence in that.

Bowen: I love that for comedy. Either your dream to pursue it is challenged or it’s reinforced and supported. Either way, we both end up in the same place where we love comedy. I always love telling people my whole story with my parents and how they have come around only recently. But I also don’t think the environment you were raised in, and how comedy figured into it, really makes a difference. If you love it, you love it, and you pursue it. And it has to be a sustained, lifelong thing. You can’t have a cursory engagement with it later on in life.

Judd: Your story is so interesting because now you come across as a very bold performer and a very confident performer, but you fought against a lot of judgment. That’s the hardest part: to be doubted or to feel a lack of engagement from your parental figures when you’re still in your formative years.

Bowen: Sure, and I’m still working through this in therapy, where I don’t know how much of it had to do with what it meant to just be a gay kid in the early aughts. All the queer people I know are, in some way, a little damaged from just the process of understanding themselves to be queer. There’s this bell hooks quote about how it’s not queerness in terms of who I have sex with or what gender I am. It’s queerness in terms of living in a world where things are hostile toward you. And I think that’s it. I think it transcends my weird little relationship with my parents.

Judd: Is it now possible to feel close and happy and celebrate this with them?

Bowen: For sure. Definitely. My mom came to the show on Mother’s Day, and we just all paraded out our moms. And then we got lunch with my dad the next day, and their whole thing to impart on me was like, “You’re able to do this, but you should realize and remember that this is very lucky, very fortuitous.” I was like “Yeah, of course.” And then, ironically enough, Lorne [Michaels] said the same thing to me at that dinner: to just enjoy and appreciate the moment.

Judd: When you’re doing something that’s working on SNL, do you feel how good it is in the moment? Or are you so focused that you don’t get the enjoyment till afterward?

Bowen: The only time that’s happened has been with the iceberg bit. I knew at the time, and I was like, I’m having so much fun. And: Thank God the audience is onboard. Because every other time I’ve done something on the show, it’s only been thinking ahead to: How are people going to respond? How do I look? Are they going to use this on my reel when I die? So, that’s been the only time. And I don’t mean to reduce it down to a mindfulness thing, but it’s something where you just feel your feet, you feel the weight of yourself, where you are, and that is enough to bring you to the moment. Right now, I’m tired, but I’m still recouping from just how exhausting the last season was. But I am really grateful to have done it. I keep wanting to frame things as luck.

Judd: What season is this as a performer on the show?

Bowen: I’ve just finished my second season as a performer. And I had written one season prior to that.

Judd: The show has also never been as multicultural as it is now, and it looks like it’s going to keep moving in that direction. That makes it very exciting to watch.

Bowen: I keep thinking about SNL as this monolithic thing, but then I remember that it aired in a completely different cultural environment when [Adam] Sandler and [David] Spade and Chris Rock and [Chris] Farley were on. I can’t believe that is the same container as what it is now. Or SNL in the mid-aughts, when it was [Andy] Samberg and [Bill] Hader and [Kristen] Wiig. Even that feels like a completely different show, too. So often, you’re only thinking of the show’s highlight reel, where it’s just the best stuff, which gives the illusion that it’s always at a certain quality level. But really, SNL has always been this weird little petri dish of ideas, and it’s just stood on the counter in the lab for all these decades. I love the fact that I don’t have that much in common with Michael Che in terms of our backgrounds and our approaches to writing and what we’ve seen in the comedy world thus far. We came from completely different poles. But now he and I have some common ground as far as working at the show goes. We had this really nice moment at the finale, where he brought everyone to his apartment at, like, 4 a.m., and he and I just had a nice little heart-to-heart. And I couldn’t believe it. I would never have expected to get this from Michael Che, of all people. Yet, there he was, with this, like, sageness that I never would have thought that I could have access to.

Judd: This was in appreciation of the show and your work for the year?

Bowen: Just for each other, in the way that we both look to each other, like, Hey, I’m so glad that we experienced this pressure cooker of a show together.

Excerpt adapted from Sicker in the Head: More Conversations About Life and Comedy by Judd Apatow, to be published by Random House. Reproduced by permission of The Wylie Agency. Copyright © 2022 by Judd Apatow