As more and more queer comedians have migrated from bar sets and showcases to Comedy Central, HBO Max, Hulu, and NBC over the past several years, think pieces and essays have showered much-deserved accolades on the growing mainstream prevalence of the queer-comedy scene. The flip side of this development is the case with all art: What was once novel soon becomes generic, and as queer comedians’ jokes — delivered from balconies, topped off with wigs, and foaming at the mouth — reach bigger audiences, the bar for fresh material rises as clichés, tropes, and stereotypes take shape. Anal-sex jokes and quips about lesbians staying at home run the risk of becoming hack — not not funny, per se, but predictable, uninventive, and easy.

That’s the case for any kind of joke, regardless of the community it comes from, but what “hack” looks like gets complicated for marginalized communities, whose points of view have been historically ignored or outright attacked. The expectations they’re tasked with subverting change depending on the audience and venue. Some jokes — say, about coming out — might seem predictable at cabaret shows filled with other queer comedians on the lineup, but those same jokes might kill at a more traditional comedy club — or bomb even harder. “Queer hack” is therefore particularly difficult to define.

A year after the release of studio movies like Fire Island and Bros, and months after shows like The Other Two, Los Espookys, and Search Party have come to an end, eight comedians reflect on the murky definition of “queer hack,” the broader concept of “queer comedy,” and the clichés they’d like to see retire.

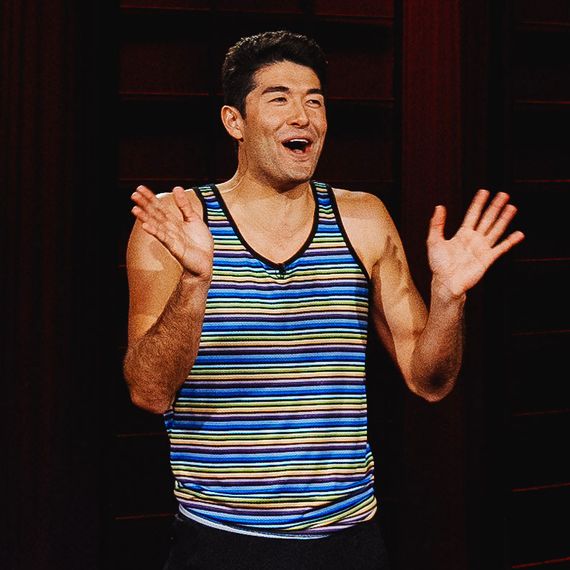

Dylan Adler

Hack, to me, is something that just feels predictable, something that’s disingenuous to a person — doing it because it is easy, or it works. When it comes to the queer alt scene, I can see when someone’s cadence is like Kate Berlant or John Early. Even something like “Hi, gay,” no one said that before and it was so funny, but everyone knows that’s Meg Stalter’s bit. When I first started, I think I was doing Ali Wong drag, doing her cadence. It took me a while to figure out and carve out my own voice and what really excites me.

I think an example of a gay hack joke or queer hack joke has some racist undertones or somehow downplays the experience of other marginalized groups, which is something I’ve definitely heard at open mics. I remember hearing one where a white gay was addressing all of the protests going on during 2020, and the joke was like, “I may be a cis white gay man, but I will always be a faggot.” I think it’s overplayed, and it’s just boring to me. It’s also something I’ve heard told in other ways too. I heard another joke that was like, “Yes, I am a cis white man, but like, what did we ever do wrong?” And the main people laughing were other white gays.

When it comes to writing my own material, I want to lead with a joke that makes me feel excited. If I can see where a joke is going, I let go of that premise. With more queer creators, the idea that we might try to find more specific, nuanced, unexpected vantage points is exciting to me. But the fact that there is queer hack excites me, because that means that there’s a lot of queer creators and queer comedians, and it’s making its way into our culture and the way we talk, and that’s what straight people have been doing forever.

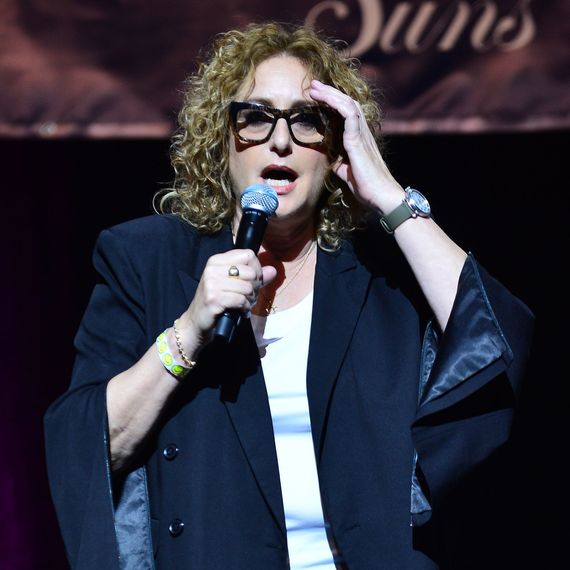

Judy Gold

It’s funny, because the first queer comics were groundbreakers. They were risk-takers. They were fearless. I came out in ’96 as a gay parent, and I was talking about things no one was talking about, so it couldn’t be hacky. I didn’t want to be pigeonholed as a gay comic or a lesbian comic. I wanted to be a comic who happened to be gay, and I did that.

It’s interesting that coming out doesn’t have an effect on comedians’ careers anymore. There’s no risk involved, or less risk, so they take the easy way out. I think with all of this acceptance — which I’m very happy for — there are more comics, and in general, they feel free, and they don’t have to try.

I just can’t with the fucking anal jokes — and the rimming, the bottom, the top. I mean, if you’re saying “I just want to work for gay men,” fine. But there’s a whole world out there. Don’t pander. Don’t do the obvious. Straight comedians did that for so long and no one cares, so maybe we’re going through this adolescence in our comedy.

Being an outsider can make you a great comic. It lets the audience see the world through a different perspective. The whole world was not set up for us. It’s about dignity, I think. So sometimes when I see hack material, I’m like, No, that’s exactly what they want. They want to hear that. They want to be able to have an excuse.

Jay Jurden

When you’re using the word “hack,” usually what you’re saying is that person is using a cultural shortcut to get to a joke that might be almost too well-trod. You’re not calling someone a copycat. You’re not even calling someone untalented. When you say someone is a hack, you are saying that person is using a bit of a cheat code and not necessarily novel. The sweet spot is sometimes a second or third thought instead of a first thought. And yes, I’m a self-identified comedy snob — we would love it if you got to that third or second thought.

I don’t know why we’re still making anal-sex and poop jokes. I understand that scat humor is funny because of the transgressive nature of scatological humor, but I don’t think every anal-sex joke needs to be a poop joke, because the poop joke is a poop joke. An anal-sex joke is an anal joke, but it’s also just a sex joke. And a lot of times when people call people “bottoms,” what they want to say is “faggot.” So the top-bottom dichotomy gets a little … [Winces.]

I think we are lucky that we live in an era where queerness is becoming so widespread that we can say, “Oh, that gay joke has been done enough.” It’s a gift that we live in a place where gay people, specifically queer cis men, are doing stand-up and we can say, “Okay, ladies, we heard that one. Do better.” It is tough to be funny to queer audiences and straight audiences, but not impossible.

When anyone describes your comedy as anything other than funny first, that is, to me, an insult. As far as queer hack stuff, if your friend at brunch is funnier than what you’re saying onstage, reevaluate yourself. Sorry.

Ryan Leach

I think that hack is the lowest common denominator. It appeals to and reinforces stereotypes, preying upon the most vulnerable for audiences outside of that community. Nori Reed has this great quote from when the Chappelle stuff was happening that was like, “If you’re a cis comic and you want to make a trans joke, you can feel comfortable and confident that there is a trans comic out there who is going to do it better than you.”

There’s this trend that I participate in actively, which is “I’m gay, but I’m homophobic.” I love that bit, but I think that it’s starting to become very popular in a way that might be targeted in a bad way. We came out of the Obama era, and then a feeling of solidarity under Trump. But now there’s lots of right-wing groomer narratives coming back up, and I would love to see comics turn that on its head. I think it really comes down to: What is the message? There’s a lot of hack, and a lot of people respond to hack by just trying to satirize it. But I don’t know if that’s necessarily productive.

Sam Morrison

There’s a queer community, especially in Brooklyn, that didn’t exist when I started comedy just five years ago, which is wild to me. But still, if you put a gay person on any lineup on any midtown show, they will stick out like a sore thumb. You still have to go up there and introduce yourself to homophobic tourists and figure out how to get them to laugh at you as a human being. Honestly, I hope queer hack becomes a thing. But to me, it feels like we’re pretty far away from that happening.

I don’t use the word “hack.” I use “overdone” and “poor effort.” The only time you’re gonna see a gay joke over and over again is if you go to all these queer shows, and that’s just such a small audience of people. I guess what I’m saying is I hope people are consuming enough queer comedy that they are starting to notice trends, but for the most part, I don’t really know if that’s a pattern yet. The people who are going to queer shows in Brooklyn enough to recognize hack queer comedy are probably 80 percent comedians.

River L. Ramirez

I guess hack is someone who panders for success and panders to laughter, but it’s a really amazing way to also see a trend happening. I try to make sure I’m seeing that so that I can work against it. I’m always trying to upset people rather than pander to them.

I get very angry about these things, because I also think that hack is a disservice to group consciousness. For example, it gets hack when Dave Chappelle makes fun of trans people, right? That’s a hack thing. These are almost cultural crutches that don’t allow the group to evolve. And that doesn’t allow group thought to evolve and doesn’t allow culture to evolve, and it’s very visible. So whenever I see anyone stuck there, I feel the job of the performers is to challenge thought, and to move it along.

What’s overplayed with a queer audience is being queer — saying “I’m gay” or “I’m trans” as a punch line. Fuck this shit. Because I think that’s playing into a job market. The demand is to be your marginalized person, to be this little thing that needs so much help, that’s struggling, that’s whatever. If your objective is to make money off of your existence, then there’s no revolution — no changing of the world or the culture as we see it.

I think the identifiers kill everything. If there is a future that’s more tangible for queer hack, it’ll be people still holding on to their identities so hard and not being able to let go and being on commercials and being like, “As a queer person, State Farm is here.” That’s where you’ll end up. It really makes you silent and complicit in allowing this industry to feed off of our bodies.

I hope there’s no queer hack, because in principle, to be queer is to break tradition, to break thought. So I hope people keep breaking thought.

Jes Tom

When I started out, almost anything I said would be very novel. I didn’t have to write a good joke because a lot of it was just a novel idea, and that was enough. And then, especially in New York, there’s such a vibrant and booming queer comedy scene of people with lots of overlapping identities as me that I had to be creative. Now people are performing with people who understand and accept them, and I think that’s wonderful and great. But it does also mean sometimes you create kind of myopic material.

Seven years ago, I was on a show that was all trans masculine or afab nonbinary people. And one after the other, I watched everybody get up and do their “People think I’m a man” joke. I was like, Oh my God, now we all have these competing jokes. That was almost ten years ago, so now there’s even more queer comedians, and the discourses of queerness and identity are so different.

I am still learning how to perform for different audiences, because I have mostly performed in New York, L.A., and the Bay Area, which are all super-queer liberal bubbles. I’ll be touring this year, so I’m going to learn how it goes in other places and how to appeal to a wider range of audiences. You can seem hack to some audiences and not to the mainstream audience.

It’s interesting that the culture has changed so much that “So I’m nonbinary” could become as proliferated as “So I’m in therapy” or “So I’m single” or some other hack premise. That is relatable to a lot of people, but it’s only going to make a good joke if you go somewhere interesting with it.

Irene Tu

Before I started doing comedy, there were only a handful of comics that were openly out and queer, so any jokes that they told, people were like, Oh my God, I’ve never heard this before. Now there’s so many of us, which is cool, but sometimes when I see new comics start out, I’m like, Oh, I have heard that joke before. If it’s a coming-out joke, a lot of them are kind of similar. I have jokes where I don’t like telling anymore, because I’m like, This is an easy, queer joke that’ll work. When I wrote it, it was true and funny, and it worked with a large group of people.

It’s hard because if I’m performing for comedy fans, I think you can get away with not pandering to them because they’re there to see a comedy show. They want to hear jokes; they want to hear something they’ve never heard before. But if you’re performing for people that are just out on a date night and don’t even know who the headliner is, you have to make sure they like you before you can even talk about anything serious or dark or grim.

Personally, I’m interested in queer comics talking about queer stuff that I haven’t heard before. Or just queer people talking about regular everyday stuff — that is probably the most interesting to me, where I’m like, Oh, we don’t have to explain that we’re gay and you’re laughing at us because we’re gay. We can just also be people and have experiences. The ultimate goal is to be funny, not to be like, gay funny.

We’re all on our own journeys trying to figure out stand-up comedy, and especially if you’re new, you’re going to do jokes that people have told before. Personally, I think we’ve moved past coming-out jokes, but if you gotta tell one, go for it. I just want to hear something that I haven’t heard before. I just want to hear queer people telling jokes about just random fucked-up shit that they’ve done — or about just being a regular, normal person.

These responses have been edited and condensed for clarity. All interviews were conducted prior to the WGA and SAG strikes.