When Sam Morril sat down to watch the first cut of his stand-up special Same Time Tomorrow, released on Netflix in September, one editing choice jumped out at him. Whenever he interacted with members of the audience, the special’s director, James Webb, had captioned their responses in large neon lettering, reminiscent of a first-generation meme or Microsoft Office Word Art. Morril liked the flourish, so he sent the cut to a friend to get a second opinion. “I don’t like that. It reminds me of Instagram,” he remembers his friend saying. “That’s why I do like it,” he countered.

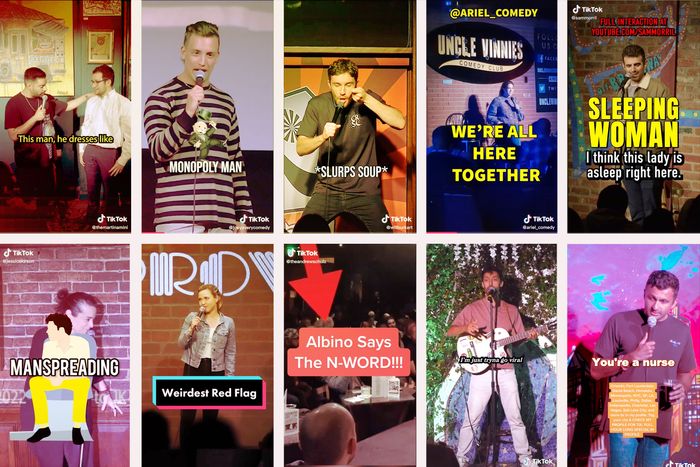

Morril and his friend were referring to the way stand-up looks on Instagram and TikTok, where in recent years captioned crowd-work clips have become the dominant way it is packaged and consumed. Many of comedy’s ascendant stars, from Taylor Tomlinson to Stavros Halkias to Nimesh Patel to Andrew Schulz — your brother-in-law’s favorite comedian who many credit as this trend’s pioneer — are all regular purveyors. But so are veteran comics’ comics like Jessica Kirson and Morril, previous unknowns who’ve built sizable followings like Will Burkart, musical comedians who sing all their crowd interactions like Morgan Jay, and open-mic’ers it would be pointless to name. All of them post multiple crowd-work clips per week that look exactly the same. They’re 15 to 90 seconds in length, framed in portrait mode for optimal mobile viewing, captioned with big block letters, and overlaid with eye-catching title cards to encourage clicks. Here are a few that have been circulating widely over the past two months:

In this clip, Morril responds to a heckler who shouts out that they’re “against apartheid” by asking them, “What’s your stance on fucking up my show?” Morril follows up by asking what the person is drinking, and they reply, “I thirst for justice.” Cut to Morrill raising his drink to his lips and saying, “Hold on one sec, I gotta take a sip of some justice here.” The clip has racked up over 2 million views on TikTok.

In this clip, Katrina Davis finds a “throuple” in the audience of an all-crowd-work show and turns her performance into a town-hall forum where she encourages other people in the crowd to chime in to ask them questions. “This is just like an interview. I don’t care if it’s funny,” she jokes. The clip has been viewed 608,500 more times than Davis’s second-most-watched Instagram Reel.

In this megaviral newsmaking clip, Ariel Elias is responding to an audience member who asks her if she voted for President Biden when a beer can whips by her, narrowly missing her head. Without missing a beat, she picks up what’s remaining of the beer and chugs it. Patton Oswalt, Jim Gaffigan, Jimmy Kimmel, and more praised Elias’s graceful handling of the assault on Twitter, with Kimmel agreeing to let her make her October 24 late-night debut on his show. It has over 5.7 million views on Twitter.

The jury is not out on the effectiveness of this strategy. Patel, a former SNL writer, says that the social-media model he adopted during the pandemic — of which crowd-work clips play a big part — is how he went from having zero shows booked in March 2021 to selling out Washington, D.C.’s 1,960-seat Warner Theatre in November 2022. These clips help comedians discover new fans, engage followers, and sell tickets for upcoming shows — all while preserving their written material for paid opportunities. Some comedians, like Kirson, have even begun tacking Q&A portions onto their shows to keep their reserves stocked.

Jack M. Angelo, a videographer and editor contracted by Patel, is one of a growing number of professionals who work with comedians — in his case on an almost full-time basis — to help them film, identify, cut, and caption the clips they post online. “I’d say a good 60 to 70 percent of comedy clubs have some kind of infrastructure for filming comedians’ sets, and I’d say a good 75 to 80 percent of those venues kind of suck at it,” Angelo says. In April, he posted an Instagram video breaking down his approach to editing a stand-up clip from start to finish. The process involves reframing the video’s aspect ratio, correcting the video’s color, cutting in different angles, and more. Prices for this service can vary with some comedians, like Gianmarco Soresi, striking an ongoing agreement to keep a professional on retainer to edit unlimited videos for $500 per month and four other comedians (and Angelo) noting that the cost on a per-clip basis is between $25 to $50, depending on the level of sophistication. Those who don’t want to (or can’t) spend the money are forced to edit and caption their clips themselves. Burkart, who went to film school, says it routinely takes him an hour to cut and caption a 30-second clip. Meanwhile, L.A.-based comedian Joey Avery says he invests between 15 and 20 hours into making clips each week. “I didn’t get into stand-up to be a full-time video editor, but here we are,” he says.

Not everyone in comedy is enthusiastic about this shift, and a debate has emerged about the drawbacks of flooding social media with crowd-work clips. “I hate to come on here and be toxic but the crowd work clips I see are really bad,” comedian Megan Gailey tweeted in August. “You can replace stand up comedy crowd work clips with census workers asking questions and I won’t be able to tell the difference,” Mohanad Elsheiky tweeted the same month.

In 2019, comedian Moses Storm performed a set for Comedy Central where he facetiously tried to create the “perfect Instagram clip” by mimicking the tropes of stand-up videos popular on the platform. “Leave some room for some embarrassing subtitles, because nothing’s funnier than reading a joke,” he instructed the set’s camera operator. He’s doubled down on his criticisms since, observing on Vulture’s Good One podcast earlier this year that comedians are no longer performing for audiences but for the algorithm. “We are now posting the most dog-shit crowd-work clips” — as if “the reason I got into stand-up was to ask, ‘Who in the front row be dating?’ and ‘Who has a job?’” he said.

Even comedians who are skilled at crowd work are playing what Patel terms “a numbers game,” appeasing an algorithm that favors quantity over quality. And it’s not just improvisational aficionados who saturate TikTok’s “For You” pages with fragments of audience banter — it’s also comics whom Kirson describes as “not seasoned” posting clips that are “not great.”

In August, a comic named Aaron Weber posted a TikTok video parodying what these clips look like at their most monotonous. In it, he asks an audience member what they do for a living, then proceeds to make tedious small talk with them about it like they’re a neighbor he ran into in the elevator. “Do you like it? Is it a good job?” he asks, unable to heighten the interaction for laughs. “All right, that’s my time,” he says abruptly, ending his set. In a more surreal take from January, Ahamed Weinberg posted a sketch that looks, at first, like a typical crowd-work clip where he makes fun of an audience member’s strange-sounding laugh. “Dude, you look like an undercover cop,” he says, getting a huge laugh from the audience. The video cuts to a montage of the audience member training and spying on Weinberg before violently confronting him in a stairwell. “How’d you know I was an undercover cop?” he says, punching Weinberg and pushing him up against the wall. “Who’s your fucking source?!”

That this trend is so ripe for parody points to the transactional nature of crowd-work clips online — an extension of how it’s used in comedy clubs as a means to an end to warm up audiences not yet loose from their mandatory two drinks. It’s the exact perception Moshe Kasher fought against when he released his dedicated crowd-work album, Crowd Surfing, in 2020 to prove that crowd work can be its own art. He’s of two minds about the current trend. He calls it “savvy” and says he wishes he was earlier on the uptake, but he also remembers “a bizarre kind of stand-up” performance he saw being filmed recently in L.A. that portends a gloomy future. “It was this extremely in-your-face, performative crowd interaction,” he says. “There was no backbone of an act to it. The comedian was pulling people up onstage and putting their hair over his head to create a wig from their hair.” And rather than help comedians succeed in clubs, in some cases, these clips are actually hurting them. Gailey says that, during a recent conversation with a comedy-club booker, he told her that he keeps getting pitched performers with 30,000 TikTok followers he refuses to book because their pages show no evidence of an act beyond bite-size crowd interactions.

What’s left is a larger question about what effect, if any, this trend is having on comedy in the aggregate. Comedy has withstood the rise of gimmicky marketing trends in the past, and each time they prove effective, there are invariably some comedians who embrace it and some who are skeptical. In the internet era alone, comics have resisted posting videos on MySpace in the vein of Dane Cook, balked at the idea that every comedian needs to have a podcast, and mocked early precursors to this current crowd-work trend like Steve Hofstetter, whose popular “comedian destroys heckler” videos continue to rake in millions of views a decade after he began posting them. Today, stand-up videos and podcasts hosted by comedians are inescapable parts of the media landscape.

Where this trend feels novel compared to those of the past, though, is the direction in which power seems to be flowing. Comedians are taking directives about how to promote themselves from the platforms they’re using rather than using them as tools to promote themselves in a manner that feels tailored to their voice. The governing aesthetic of social-media crowd-work clips was never agreed upon by the comedians who capitulate to it; it just happens to be the one optimized for the algorithm. Adhering to it enough times is how a young comedian might end up in millions of “For You” pages and become a viral success overnight. It’s like pulling a slot machine — chaotic and unpredictable in a way that Kasher points out is not unlike crowd work itself.

Gailey believes crowd work is supposed to be ephemeral and that trying to recapture its magic on social media is a doomed and pandering exercise. “We’re playing to the lowest common denominator, and I don’t think that’s beneficial for the audience or the comedian in the long run,” she says. But even though she doesn’t post crowd-work clips on social media herself, she understands the need for comedians to participate in the game. She’s resigned herself to this reality and recently contracted a professional to go through her backlog of stand-up material to cut together short clips for social media. “I’m probably a hypocrite,” she concludes.

None of these criticisms are lost on the comics who’ve adopted this model, either. Even a savant like Morril concedes he takes less pride in the crowd-work clips he posts than his written material, because audiences see crowd-work clips as off-the-cuff magic tricks and lower their standards as a result. “You can take something that’s not quite as funny as a written joke and kill even harder,” he explains. But he acknowledges the reality that comedians in 2022 are content creators who most feed the insatiable beast. “I’ve often said the demand for content is killing comedy. But I’d rather not sink.”