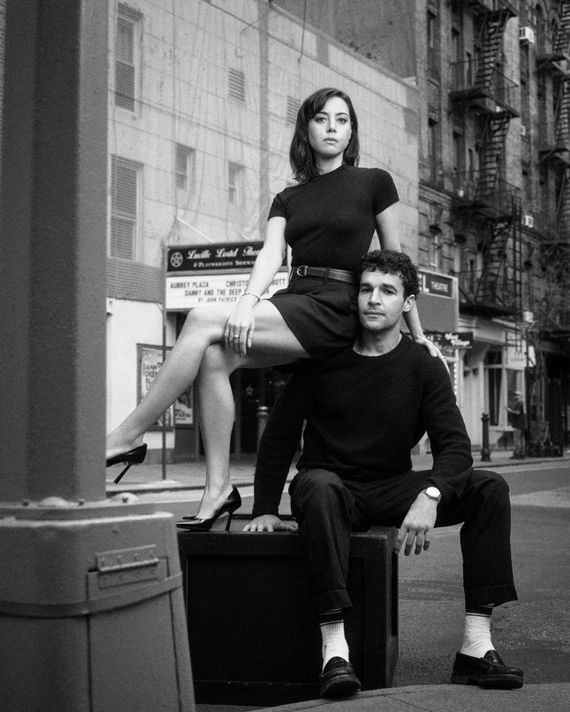

Is a slap worse than a grope? Does a push (on the forehead) hit harder than a pull (of the hair)? These were the questions that occupied Aubrey Plaza, Christopher Abbott, and their director, Jeff Ward, during a recent rehearsal for the Off Broadway revival of John Patrick Shanley’s Danny and the Deep Blue Sea. The play follows Danny and Roberta, two Bronx down-and-outs who open their hearts to each other and frequently draw blood. In Shanleyville, emotions are operatic, accents are outer-borough, and a kiss, as Dean Martin once sang, is a kick in the head.

On a rainy Monday at a dance studio across from City Hall, the actors were rehearsing a sequence near the end of Scene One. Danny, who calls himself “the beast,” has just confessed to killing a guy in a fight (he thinks). When he viciously rebuffs Roberta’s attempt at connection, she shows her own beastly side. Plaza was standing above Abbott, berating him with a stream-of-consciousness string of sexual insults — “Do you get off on pigs rubbin’ their shoes on your ugly dick-lick face, you lowlife beefcake faggot?” — after which he would explode out of his chair and choke her. Ward had already cut a slap later in the play that felt too much like “Jake LaMotta fanfic,” but he kept the choke. “It’s not an act of violence; it’s actually an act of restraint,” he told the actors. “He’s like, ‘I’m holding back 99 percent of what I want to do.’”

A fight coordinator named Drew Leary was on hand to give Plaza a “bag of tricks,” different ways she could fuck with Abbott in the monologue to show Roberta isn’t intimidated. First, she tried out a light slap. A quick brush with the backs of her fingers across his cheek. A maternal cuff on his hairline. “Look, I’m just really gonna hit him sometimes,” Plaza joked. “It’s all about the fingers, right?”

“I taught you that,” Abbott said proudly.

The greatest legacy of Danny and the Deep Blue Sea, which premiered in 1984, may well be giving generations of theater students something to audition with. It’s a short play with big swings, all ripe for undergraduate emoting. Danny, a construction worker with a murderous temper, and Roberta, a single mother going mad with self-disgust, are desperately in need of love but would sooner lash out than accept it. “It’s almost trite,” Ward said. “Like, ‘You want to do Danny? Of course you fucking do.’”

Ward and Abbott have been friends since 2009, when they both tried out for the same role in Polly Stenham’s That Face. (Abbott got the part; Ward became his understudy.) Ward, best known as an actor on Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., is making his professional directorial debut. But he had long seen “an unmined diamond” in Danny and the Deep Blue Sea. The two pals were often underwhelmed by new dramas, many of which felt as flat and talky as TV shows. Now, thanks to Sam Rockwell’s production company, they were getting a chance to make the kind of play they wanted to see. “I want to be witnessing something I shouldn’t be witnessing,” Abbott told me. Otherwise, he said, why do it live?

At the studio, the actors were workshopping Roberta’s whacks, making sure they escalated in the proper rhythm. The first hit couldn’t be too aggressive or it would overshadow the blows to come. Abbott remembered Plaza once trying a two-fingered swipe at his temple, like something a bully in an ’80s movie would do. They tried it again and found it the ideal mix, demeaning but not threatening. “It’s literally poking the bear,” said Abbott.

The last hit was crucial, as it would prompt Danny’s outburst. “It’s about insulting your manhood. That’s the thing that pushes you,” Leary told Abbott. “What if the final thing was not a moment of violence?” He grabbed Abbott’s pants near the inner thigh. Ward liked it. “What she’s saying is annoying, but what makes him be like ‘Get the fuck off me’ is when it gets into the sex-love zone.”

The downtown scene’s relationship to tales of the white working class has changed significantly since the ’80s, when kitchen-sink romances like Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love and Terrence McNally’s Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune flourished. Danny is now resolutely off-trend for contemporary theater, due to its semi-comedic domestic violence as well as the fact that it’s not about American history, generational trauma, or millennial ennui. “This play would not be written today,” Plaza said. “But that’s what’s so interesting about doing it now.” We were in the dance studio, chatting before the next day’s rehearsals began. Plaza had brought crackers, avocado dip, and rolled dates. “I’m much more of a people pleaser than Chris,” she said. She recalled reading Shanley’s play and feeling like it was “ripping your heart out.” “It’s so sincere,” she said. “Everything today is dripping with disdain.” Plaza is half Puerto Rican, while Abbott is part Italian; both identified with Danny’s lack of Waspish piety.

Abbott has appeared Off Broadway a half-dozen times and on Broadway once. Plaza never went to an acting conservatory and says she has impostor syndrome with theater. “Chris and I are giving her four years of theater school in a couple months, and she’s taking to it like a duck to water,” said Ward. To loosen them up, the director had them do animal work, a Strasberg technique in which actors play a scene in the spirit of, say, an ostrich. After weeks of rehearsals, they bust each other’s balls like siblings. While practicing the choke, Plaza urged Abbott to be careful: “I got a loose neck.” He fell into the voice of a neurotic New Yorker: “It runs in my family! I grew up on Loose Neck Farm!”

The pair first worked together on the 2020 metafictional drama Black Bear, which Plaza produced and which shares with Danny an interest in fucked-up gender dynamics. Abbott plays both a reactionary boyfriend and a manipulative director; Plaza is a pot-stirring temptress, then an actress who explodes in jealous rage. Plaza said she wrote Abbott a letter that she never sent, begging him to be in it. “In my opinion” — she lowered her voice to sound as unpretentious as possible — “he’s the best male actor in our country today.”

For Danny, Abbott returned the favor: Plaza was the first actress he thought of. “Aubrey’s got a Gena Rowlands thing,” he said. “The kind of energy you see in Cassavetes movies.” They learned they felt safe with each other. Shanley’s play can be dangerous for an actor — all those slaps and chokes. “Aubrey can trust me to be wild and have restraint at the same time,” Abbott said.

While doing the play, Plaza is living on the Upper West Side with Patti LuPone, with whom she recently worked on the Marvel series Agatha: Darkhold Diaries. LuPone has since become something of a surrogate mother, making Plaza soup and doing her laundry. “She insisted,” Plaza said. “She’s trying to whip me into shape.” One day, she was attempting to put into words the different sensation she felt onstage, compared with being on-camera. “It’s a thing I feel like I don’t know. Patti said, ‘The performance is lifted.’ It made sense to me.” Shortly before rehearsals started, Plaza came down with a bad case of strep throat. “I was like, ‘Why is this happening?’ Patti went, ‘It’s happening because you have to toughen up.’”

Danny is usually done black-box minimalist, but Ward’s big idea was to marry the bleeding emotion of the text with the theatrical spectacle he admires in the works of Ivo van Hove. The spark came from the play’s subtitle: An Apache Dance. What if he added choreography?

At first, he worried he would get in trouble for cultural appropriation. Then he learned Shanley had gotten the term from a dance popular in France in the early-20th century: a rough, romantic pas de deux suggestive of a prostitute overcoming her pimp. Satisfied no one would be canceled for imitating a bunch of dead Frenchmen, he ran the idea by Shanley. The playwright assented in theory but reserved the right to change his mind once he had seen it. On the advice of a producer, the team brought in the acclaimed husband-and-wife choreographers Bobbi Jene Smith and Or Schraiber, who had just used Danny as an inspiration in their show Broken Theater.

That week, Ward’s vision was on the line. Shanley would visit in a few days. He would either approve the dance sequences or not, in which case they would be scrapped. “I still think it’ll be good, but it’ll be much more basic,” Ward told me. The actors were at MSNBC for an appearance on Morning Joe, and in their absence, the director was involuntarily shaking. “We are running out of time,” he kvetched to Rachel Bauder, the stage manager. She tried to talk him down. He was working with experienced professionals who had all done their homework. No one would be tearing their hair out. “I will be tearing my hair out,” he replied.

A few days later, the clouds had passed. Shanley had formally given his approval, and the team was in good spirits. That afternoon, Plaza’s dog, Frankie, would be arriving from Los Angeles. “She doesn’t let everybody in,” she said. “You have to be calm and then she’ll come to you.” Abbott walked in: “You talking about Patti?”

Today, they were rehearsing a dance duet for the transition between Scenes One and Two, when Danny and Roberta decide to spend the night together. “I’ve heard someone say it’s the worst transition in American theater,” Ward told me. The end of Scene One is “so raw and so emotionally heightened. And then a bunch of people in black T-shirts come out and switch over the set.” Ward hoped the inclusion of dance would keep the emotional momentum going. Movement allowed Danny and Roberta to step outside themselves and express the inner lives they can’t fully articulate. “They are too much for this world, these broken people,” Smith said. “The world can’t contain them, but they could contain each other.”

Smith was away working in Basel, but Schraiber was in town to implement the choreography. The actors ran through the duet, Plaza in a Bowie T-shirt and leggings, Abbott in JNCO jeans. As Otis Redding played on the sound system, they held hands and swayed like middle-schoolers. Soon, the dance opened up, got more modern. The couple came together, then apart. Some moments were surprisingly funny, and others read as a challenge: Roberta wondering if Danny could overcome his self-hatred and provide the love they both needed. Plaza kicked her leg between Abbott’s; he slapped it. Then the music shifted. Suddenly, they were grappling, clawing each other’s chests, their anger mixing with frenzied lust. The duet was, in part, a metaphorical sex scene, but by the end, it was a lot less metaphorical. “It has to realistically get to orgasm,” Ward said. Abbott interrupted, “Have you ever seen, in porn, milking?” He mimed a hand job. Plaza covered her face with her hands, then made the sign of the cross.

The actors thought one sequence, a box step, didn’t have enough pizzazz. “It feels like we’re filling space,” Abbott said. Schraiber proposed a few variations. Abbott might fall onto his back, then crab-walk backward while Plaza crawled over him. Or they could do a move called “69,” which is exactly what it sounds like: Abbott would hold Plaza upside down and they would both scream. Was that too much? “I feel like the 69 won’t work without the screaming,” said Schraiber. It was too much.

“What if he just threw me?” Plaza said. Schraiber went inside himself for a minute and tried out moves. Maybe they could slap each other on the ass. “Like a horse,” said Abbott. Could Plaza crawl down his back? Definitely not.

Then Schraiber had it: They would stand next to each other, go into a sideways dip and then a full drop that, if done poorly, looked liable to rip Plaza’s arms out of their sockets. Was it doable? The actors double-checked their grip, then ran it again. “It’s actually more about me doing it,” Plaza told Abbott. “I flip myself, then you pull me up.” Abbott placed a pillow from the set on the floor just in case. He looked at Bauder. “Rachel’s writing down the numbers of local hospitals.” They ran it again. It looked good. The next time, it looked even better. The last time was the best of all. Schraiber kicked the pillow away in triumph.