When we meet the Frederick Douglass of The Good Lord Bird, he’s in front of a crowd of well-heeled ladies, delivering one of his seismic speeches. The ladies giggle and smile and practically faint, starstruck by the most famous formerly enslaved man in the world — hell, possibly the most famous man in the world at that time. Douglass is basking in every minute of it and simultaneously trying to wave off his friend and sometimes collaborator John Brown, who has shown up scraggly and wanted by the law. For a role of this magnitude — a powerful presence, a booming voice, and impeccable comedic timing — you can’t cast an unknown. Which is why casting Daveed Diggs, who as Hamilton’s Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette could turn out more words per minute than the average human brain can comprehend, makes perfect sense: the voice, the presence, the self-assuredness to stand in front of a sea of people and know they’re in it with you.

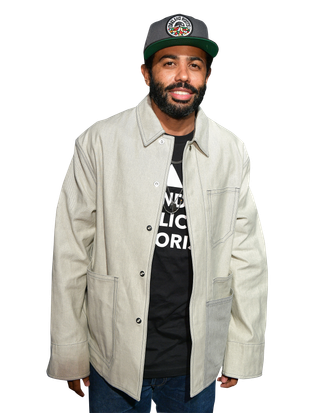

The Douglass of James McBride’s novel, which served as the blueprint for the show, only occasionally slips in, but every minute he’s on the page is mind-bending. That Douglass, brilliant and inspiring, is also a lech who tries to feel up Onion — the young enslaved boy (dressed as a girl) brought to his home by Brown — as well as an egomaniac in love with his own mind. He embodies a million contradictions, a human hero rather than a perfect one. Vulture talked to Diggs about bringing that character to the screen, playing opposite Ethan Hawke’s absolutely volcanic energy level as Brown, and why, after several requests, this is the first time he agreed to play Douglass.

What was your relationship with Douglass’s legacy and work before the show?

I had read one of the autobiographies — I can’t remember which. Or I had been supposed to read it, which means I probably read about a third of it. I had read some of his speeches, so I always thought of him as a brilliant orator and a great writer and understood the broad strokes of his life as told by himself. But that was about it.

So once you got the part, did you go on a binge?

I did. I read a bunch of his autobiographies. I read David Blight’s biography, which is, I think, the most recent of them. And then, obviously, McBride’s own words. The character, in terms of how I would play him, is right there in the novel. But I did read a lot of Douglass. What isn’t in the novel is his Fourth of July speech [“What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”], which I was being asked to perform. That’s how we meet Douglass, giving his Fourth of July speech, which is among the greatest speeches ever given. Because of that, I felt like, Well, in order to do that, I should really know this guy, and went and did a lot of research — in fact, more than I’ve done for anything. I’m not generally big on research. [For Hamilton] biographer Ron Chernow was there with us in rehearsals. So I could just turn to him and be like, “Hey, would Thomas Jefferson do this?” And if he said yes, then I would do it. [Laughs.]

How did you become a part of The Good Lord Bird?

I was doing a Suzan-Lori Parks play called White Noise at the Public. And Ethan [Hawke] came inside, and the next day we went out to coffee and he handed me the novel and said, “Hey, look, I’m doing this. I’m adapting this for television. Frederick Douglass will be in two episodes. One of them is his episode.” He’s like, “Don’t answer now. Read the book, because it’s a particular take on Frederick Douglass. And when I went home, I started reading the book and I could not put it down. I read it faster than ever. I’m a very slow reader. I think I read that book in two days and called him back.

Yeah. It’s a wild ride.

Oh my God. It’s so much fun. That dude [McBride] is a force of nature. How about Deacon King Kong? It broke my brain. It’s so good.

So you read the novel and then what made you say yes?

Well … it’s not a goal of mine to play historical figures.

Really? Are you sure?

[Laughs] Yeah. It’s not on my vision board. But I’ve been asked to play Douglass before. I’ve said no every time, for plays or for other movies. I’m not really interested in the hero worship that we normally do with our biographies. I don’t think it’s useful. I think dehumanizing people like that makes it very difficult to appreciate how amazing they are. And so then to read this portrayal … The brilliant trick that McBride did was framing everything through Onion’s eyes. It’s a cross-dressing slave boy, which allows so much to be ridiculous! Imagine you’re a 13-year-old slave kid and you come across Frederick Douglass, the most famous man in the world, who has a Black wife and a white mistress and lives in opulence in the North. Of course he’s ridiculous. That feels honest to me.

This is not a flattering portrait of his personality by any means. He’s really full of himself. Like that moment where he sort of stops mid-conversation and starts furiously writing down everything he’s saying. He is the best orator in the world, but he also knows he is the best orator in the world. Does it worry you at all that people might be put off by the fact that there is no hero worship, like you said?

I don’t worry about it. Obviously, I’m inside of it, so who knows how it’s going to read to people, but making him a celebrity who is aware of his celebrity is a really interesting conflict. It’s one that I deal with. It’s actually a thing that I understand. It makes the import and honesty of some of his work even more impressive. He’s the most photographed human being of that time. More people knew what Frederick Douglass looked like than anybody else in the world. They were shipping his books all over the world in order to promote abolition. And what you find out when you read multiple of his books is that he was totally mining his past in this very pointed way. Being like, Oh, okay, well, this book is going to be aimed at ladies at this particular tea party in the North. So I’m going to reimagine this story from my childhood, like this. He’s very intentional about it.

I think the other amazing thing is Frederick Douglass is so full of himself that he doesn’t realize that Onion isn’t a girl, whereas every other Black person in the story does immediately. And I think that’s amazing, because his world is moving so fast. He’s pulled in so many different directions that he doesn’t have the option of thinking about things outside of himself. It all is exhausting to him.

There’s a line in the novel about how Douglass’s hands start wandering down Onion’s body. Onion says “toward my mechanicals.” Was that something you guys particularly drew back on a little bit?

I didn’t write the script, so I don’t know. I assume so. I assume there was a point where they were like, “We can’t come back from this.”

Your voice is a defining characteristic of who you are as a performer, but we don’t know exactly what Frederick Douglass sounded like. There are no recordings of him. How did you prepare?

I found what claims to be a very scratchy, directly-into-wax recording of him giving a speech. You couldn’t make out a ton of it, but what you could make out was just this incredible power in his voice. When you see him, it sounded like the instrument that you looked at when you think about somebody who speaks all the time with no amplification and who has an incredible vocabulary. And also he’s in the business of getting people emotionally invested in his cause, so those things point to something that sounds like formal training, even though it wasn’t. He taught himself. I think he had a really keen ear for the kind of speech that people of the time respected and then, in my imagination, made himself the best of that.

I love how the audience that’s watching him is almost like that 1963 Ed Sullivan Beatles clip: ladies fanning themselves and sort of falling over. Did you feel like, I kind of have to make Frederick Douglass sexy?

Yeah. I mean, me and Darnell Martin, who directed that episode, talked about that a lot. He was a rock star. And so that was really important for her to get in there. You know, he used everything in the toolbox. He was raising money to free the slaves, and that was part of it. And he would speak at these ladies’ socialite events. And if it’s going to make people give money …

That hair is impressive. How much of that is yours?

Oh, it’s all my hair. We just combed it out.

It’s a defining characteristic of Frederick Douglass that he has this mane.

I couldn’t cut it, and I couldn’t really shave my beard because of Snowpiercer. Actually, if we were doing a period-appropriate Frederick Douglass, he would have been clean-shaven and the hair would have been in a much different style. This would have actually been a younger Douglass. But it feels like what we got closer to was kind of the more iconic one, the one that existed in most of our popular memories. And it fortunately worked out, because I couldn’t cut anything.

That dinner-table scene is a lot. It’s these two forces who are sort of crashing into one another. What can you tell me about filming that scene? Was any of it improvised?

With Ethan and with Darnell, there’s always room for some improvisation. That scene had a lot of moving parts. It’s actually hard to shoot a dinner scene where everyone’s sitting around a big table. The coverage is tricky. And timing everything for when the wait staff comes through and everything to pick up the dishes. So maybe less improv in that scene than most.

The thing about working with Ethan is, once action is called, that dude is in, and you just kind of hold on. And he’s so good. It’s really easy to get just wrapped up in what he’s doing and forget that you’re also in the scene.

Working with him, there’s no rules. Because he’s going to do anything, it gives you permission to do anything. And so you never get the sense that I have to hit this mark in order to allow him to do the thing that he has to do. He is not worried about it. He is going to live in this moment. And whatever you need, there’s no way you can throw that guy. Once John Brown turned on, it was on, which allowed me to do things that I haven’t really gotten to do a lot in the television space, to be that committed to a moment. You don’t get to do that often in TV. TV is often about making things smaller.

What else was improvised?

The scene where John Brown and Frederick Douglass are arguing over the maps and Onion is just trying to give them the lemonade was one of the wildest things. I mean, that is just so funny. It’s almost all improvised. That kid, Joshua [Caleb Johnson], is really something else. The drawing-room “seduction” scene, we shot that straight through. That’s a 15-page scene. And he was right there with me the whole time. That kid’s going to be a big, big deal.

It’s hard to do quiet and make an impact, but he does. I’m trying to imagine somebody saying, “Okay, you’re going to be this relatively calm and sedate little person standing next to Ethan Hawke as John Brown and Daveed Diggs as Frederick Douglass, but you have to make your performance important.” That’s huge.

It’s a lot. And it’s also just fun to see him now doing press for the last few months, Zooms all the time. Of course, he’s a teenager, so he gets a foot taller every time I see him and his voice is all deep now. It’s just wild. If it had been six months later, he couldn’t have done it.

Had you seen Ethan’s John Brown before the cameras started rolling?

I hadn’t seen him do a scene yet! The first thing we shot was the scene where they show up and I show them the basement where they’re meant to escape. I had John Brown right there for the first time. [Laughs.]

There’s this line in the Fourth of July speech where Douglass says, “For revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.” Was it hard to give that speech knowing that the same things Douglass was saying then you could say right now?

I think it’s why we need to bring that speech up every Fourth of July. It sucks that that is true, but it is not hard to say, because it’s always been true for me. There’s never been a time in my life where that wasn’t true.

It’s funny. I’ve been part of all these pieces that every time one comes out, it’s like, “Well, it’s incredible because it’s happening right now, because it’s so relevant.” When we put Blindspotting out in 2018, it was like, “Well, this is really hitting home right now.” But we started writing that in 2009. About Snowpiercer, people said the same thing: “It’s so prescient. You couldn’t have possibly known, but isn’t that amazing?” Well, yeah, but climate change was [already] a fucking thing. It’s always been a thing.

Every year on the Fourth of July, every American should have to read that speech and take stock of it and say, “How far have we come? What work do we need to do?” It’s a really good barometer.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.