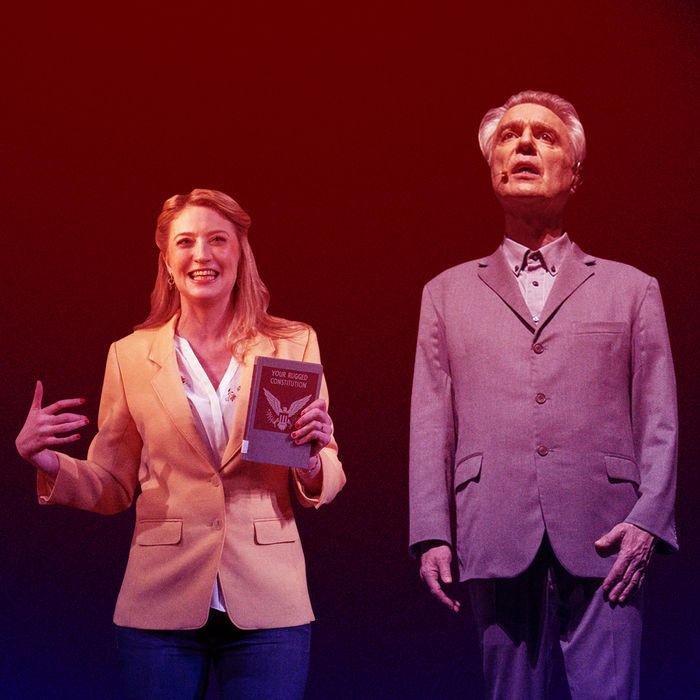

Watch American Utopia and What the Constitution Means to Me back-to-back, and you can see a conversation between them start to develop. In the latter production, out on Amazon, the playwright and star Heidi Schreck travels back into the mind of her 15-year-old self, taking the premise of the speeches she gave about the Constitution — in order to raise scholarship money — to their logical extreme. As the show goes on, she wonders whether the American Constitution works, whether it deliberately leaves room for numerous forms of oppression, and if it might be worth abolishing in pursuit of a different, closer-to-utopian document. In American Utopia, out on HBO, David Byrne goes on a kindred journey in musical form, interspersing songs from throughout his career, from the Talking Heads forward, with anecdotes about neurochemistry, Dadaism, and voting. Both acknowledge the violence and despair inherent in America right now, though both end on what Schreck dubs a potentially hopeful question: “Can we imagine something better?”

Byrne and Schreck are fans of each other’s work, and they agreed to have a conversation about the links between their Broadway productions, whose filmed versions premiered this month. They also discussed playing versions of themselves onstage, how they thought about their whiteness while making pieces about America, and what they might change once they can perform live again.

Both of your shows are about the question of what it takes to imagine a better version of America, whether through a constitution or a kind of ecstatic emotional experience. Did you see those similarities?

Heidi Schreck: David, I’ve watched your film a lot now, maybe four times, in part because I have two newborn babies and they really like the soundtrack. It’s occurred to me that when I listen to it right now it makes me feel joyful, but not a Pollyanna kind of joy. Many of us need to feel joy right now. I was thinking about it in relation to my play, some of the things I’m exploring in terms of the failure of our laws to allow many of us to thrive. The thing I’m fighting for is the ability to feel that kind of joy that you embody. They both deal with darker aspects of America, but I came out of watching your piece with such a feeling of hope.

David Byrne: I saw your show when I was still shaping what ended up being my show on Broadway. I came out thinking, “There’s something that has all these ideas in it that I’m thinking about. This is on Broadway! Who knew that kind of thing that would bring us together and talk about these things could happen on Broadway?” I was also knocked out by the comfort of your relationship with the audience. I was saying to myself, You have to try and learn how to really be talking to these people. That’s where the bar has been set, and I have to try and do that.

Both of these shows depend so much on the interaction with the audience. When you’re putting together a filmed version, you don’t have that immediate feedback, but of course you do have the ability to reach many more people than you could on Broadway. How did you think about that trade-off?

Heidi Schreck: I don’t know about you, but I felt a great deal of pain about freezing that piece in time. It changed night to night, the debate was actually extemporaneous. We changed things depending on what was going on in the country on any given day. But I thought about the fact that I grew up in a really small town in Washington and didn’t have access to theater. I grew up watching old VHS tapes of Sondheim musicals and my mom’s record of The Glass Menagerie. I felt like I was making peace with a less perfect version of it going out into the world so that maybe someone like me could experience it.

David Byrne: I’m very happy now that I can get to all these people who either couldn’t afford Broadway or don’t live close by. You never know how it’s going to translate. Overall, I felt very good about it. [Laughs.] With music, you never know how it’s going to come across.

Heidi Schreck: I do think we got very lucky with our directors, with Marielle Heller and Spike Lee.

David Byrne: What was your experience there, with how it was shot?

Heidi Schreck: Mari really wanted to focus on two things: getting closer to me than you can get in a theater so you could have that feeling, especially in the second half, that I was talking directly to the viewer. More importantly, she wanted to try to capture a sense of what the audience-performer relationship was like. I’ve acted my whole life, and I’ve never done a play where I felt so close to the audience. Their emotional reactions were bigger and louder than any play I’ve done, maybe because the play does confront certain kinds of trauma. She wanted to include them as a second character in the piece. I will say this, though: It was terrible for me because we lit the audience and so I saw their faces for the first time instead of feeling them out in the darkness. The first show we did I felt so naked, I think it was a pretty terrible performance, so I only had that second try. But when we were in editing, I spent a whole day just watching the audience watch the play. I felt like there was a whole movie you could put out, which is watching an audience watch a play.

David Byrne: The audience was not intimidated by having the lights up?

Heidi Schreck: It felt like at the beginning we were all intimidated, and when the story started going we all forgot.

David Byrne: We kind of did the opposite, where for the most part, we did not show the audience. I’ve discovered with live music audiences, if you bring up the lights they get very inhibited. But the good thing about music audiences is that they’ll yell out to the stage, which you would never do at a play.

You’ve been performing like this longer than I have, and there’s similarities to being a stand-up comedian. We’re both just standing there talking to the audience. How you deliver a line or what comes before or after it can make a huge difference to how people appreciate or laugh at it. I was constantly amazed at looking at myself and the audience watching this process work, or not work at certain nights.

Heidi Schreck: Steve Martin came to my show and he said that: “It’s just horrible, right?” Two nights it’s glorious. Four nights it’s like, eh. Two nights you just bomb.

David Byrne: I would tend to blame myself. I botched that line. I put the emphasis on the wrong word. I was fidgeting when I said it. Luckily, I could go, “Oh, I’ll go into a song. They’ll like that part.”

Heidi Schreck: Do you have any performer rituals?

David Byrne: I would make myself some ginger lemon honey tea. It’s more the ritual of cutting the ginger and putting the water in the thermos.

Heidi Schreck: I drank that ginger tea, too. Then right after, always. I would go into my dressing room and have a cup of tea.

David Byrne: I would have it after, but then I would put a little shot of booze in.

Heidi Schreck: Bourbon!

Do you think of the versions of yourselves onstage as characters? How are the “Heidi” or “David” onstage different from the actual you?

David Byrne: Well Heidi, I just love the thing of going back to your 15-year-old self without doing a little voice or mannerisms. To me that brought home the idea of how much we change over time, and yet we still inhabit more or less the same body. In my show, I’m thinking of my younger self as a different person. I refer to myself as “I,” but part of it is me referring to that person as “he,” as somebody outside myself.

Heidi Schreck: I started to do that too. When I was constructing the show with Oliver Butler, I often had the feeling that part of what the show is about is all time existing at once. My 15-year-old self is always here, and my 49-year-old self is always present. I wonder that about you, David, because some of the songs you’ve sung for a long time. There must be a sense of the same body traversing through time singing this song.

David Byrne: Exactly. Those are songs I would never write now, or could never write now. There’s a sense of when I’m performing those songs that I’m channeling the concerns and quirks of that younger person. It really is a little bit of time travel.

You’re both at the center of these shows, but you make these gestures about the limitations of your perspective, and specifically your whiteness. Heidi, at the end of Constitution, you debate with these young women of color. David, you perform Janelle Monáe’s “Hell You Talmbout” which includes a litany of names of black people killed by the police. How did you think about what your race means in terms of how you talk about America?

David Byrne: It’s a tricky thing. I really asked band members. As I say in the show, I wrote to Janelle Monáe and said, “What do you think?” I have not lived this experience. But it’s also my country too. It’s my culture as well, and I need to engage with it. I can’t step aside and say, “Oh, that’s not me.” That’s something I felt in recent years, that I do have to engage. I have to connect with other people, whether it’s band members or whoever, and say, “What did you think of this?”

Heidi Schreck: That song is such a powerful moment in the piece. It seems like a really important part of your show. I wonder how people have reacted to it?

David Byrne: Sometimes when we were doing it in our concert tour, we got negative reactions. A concert audience is maybe more diverse than a Broadway audience. We’d get people who would just shout out, “Bullshit!” or whatever. We’d see people walk out. As a performer, that’s not a happy feeling. But we also got feedback from audience members saying, “I’m glad you did that, even though that was not the happy ending we were hoping for.”

Heidi Schreck: I’m glad you did that too. When I think about both our shows, I think my play does end on a hopeful note. It’s a very hard-won kind of hope, but I am always questioning it and always struggling with it, because I do think, as a white person in America, I don’t fully trust myself to speak to hope.

While working on this show, I thought about that a lot, especially when I was talking about legal cases that had to do with women — understanding that the laws that are bad for me and for my ancestors are ten times as bad for black women, for trans women, for women of color, for immigrants, for women with disabilities. Near the end of my section of my play, when I talk about, why don’t we have explicit human-rights protections? Why do we venerate this idea of a neutral Constitution? I really struggled with that, trying to acknowledge that this document benefited a certain kind of white male property owner from the beginning and left out everybody else. It’s doing something similar today, and I am one of the people who’s getting the benefits and also acting as an oppressive force. I started this play ten years ago. I think if I were starting it today, I would grapple with my own whiteness and my own complicity in a white-supremacist culture in a more overt way. I talk about it in the play, and I try to keep the bigger framework in mind, but I think I would deal more head-on with my place in the oppressor class.

But when it came to the debaters, we did an open call at first for young debaters in the city, and Rosdely Ciprian, who was one of the first debaters to show up, was just the best debater. A young Black Dominican-American teenage girl who happened to be brilliant, so I just took it from there.

David Byrne: Your show doesn’t have a prewritten ending, but you do get a feeling of hope that all these things have been brought up to see the light of air. The act of talking about these things gives one a sense of hope.

Can you tell me about reactions people have had to your show? Whether people feel like it’s too much information about your family, or that you could even conceive of abolishing our founding document?

Heidi Schreck: There was always a small group of walkouts as soon as I started talking about having an abortion when I was a young woman. There were people who wrote me letters about, how dare I consider abolishing the Constitution, or calling me an idiot and a moron and a communist for calling the Constitution a living document. Now that originalism is such a fad, a lot of these people really want to defend the document as a dead thing.

In terms of the personal stories, I only got positive feedback. I had a lot of people wait for me at the stage door to say, “I went through what your grandmother went through,” or “We have this story in my family.” Statistically, it makes sense, given how many people are affected by familial violence and by sexual assault. That part of the play was the scariest thing for me. I had to talk about how these laws had affected my life, and in order to do that, I had to talk about the things that are considered taboo to talk about, which is abuse and assault and abortion.

David Byrne: I don’t have any good stories like that. Although … I don’t say it explicitly, but I do imply in the show that at an earlier part of my life, I might have been somewhere on the Asperger’s spectrum. Certain people pick up on that if it’s part of their own life, or part of the lives of their friends and family. And Heidi, as you were saying with the things you talk about, it enables them to think about that as something that they are not alone in dealing with. It doesn’t mean you’re a bad person.

Heidi Schreck: I hate it when people ask me this question, but I wondered about your title, American Utopia, and how it came to you. I really like the word utopia because it means both things, right? A good place and also no place. I loved that your set is this shimmering gray, which feels more like no place than good places, and yet there’s a feeling of such goodness in the piece. I felt like I was watching you in limbo.

David Byrne: I like the limbo interpretation. It could go wrong, and could maybe not. The title was actually suggested by a friend as I was finishing up my last record. I was thinking about utopian communities a lot. I had this idea to do a TV series where each episode was ten-minutes long and set in a contemporary utopian community, and we thought it would allow us to have these dances and rituals these communities made up. None of that ever happened.

Heidi Schreck: But you did have Annie-B Parson’s beautiful dances!

David Byrne: And my friend said, “Why don’t you call it American Utopia?” At that point it was an album title. I thought, How am I gonna live up to that? I was very lucky, in the sense that people did not think I was being Über-patriotic and saying we live in a perfect world. They seem to understand this is about being in a kind of limbo where you were working things out.

Heidi Schreck: My title, on the other hand, so many people just hate it. People don’t get that it’s a title meant to reference a generic high-school speech contest.

David Byrne: Really? That’s what I loved about it.

Heidi Schreck: Everybody’s always like, how do we market this show with this title that sounds so boring?

There’s been an announcement that American Utopia will return to Broadway next fall, and What the Constitution Means to Me was just starting a national tour when everything shut down. What do you see in the future for these pieces?

Heidi Schreck: There’s a plan to open the tour back up when it’s safe to go to the theater. You have a date, yes?

David Byrne: It’s a little under a year from now, which still seems a long way off, and within the realm of possibility.

Heidi Schreck: I hope so. Workers in the arts in this country are really suffering right now. Those will be the last people to go back to work. Every day I wake up in a rage that our lawmakers care so little about art and theater and performance and aren’t offering any support for those workers. It’s not just the performers, it’s the people working backstage and front of house and in restaurants around the theaters.

David Byrne: It’s that art is seen as synonymous with entertainment as a kind of dessert after you’ve done your regular part of life, instead of an industry.

Heidi Schreck: That it matters spiritually and financially.

David Byrne: It’s going to be strange to go back in after being on pause for this long. I’m asking myself what I change now. So much has changed this year. I haven’t tried writing new things or anything yet, because who knows what’s gonna happen next week, but I feel like I have to acknowledge where we are at that moment, whenever it settles.

Heidi Schreck: I can’t write anything right now. I don’t know what kind of art I want to make coming out of this moment, or what this moment even is. But I am interested in performing the show again after this, in part because it does have flexibility. The debates we updated every night. I’m interested to bring it into a post-pandemic, postelection world and see what happens.

This interview has been edited and condensed.