Never has Eddie Redmayne looked as good as he does in The Day of the Jackal — specifically in the several sequences when his assassin character, the eponymous Jackal, dons painstakingly constructed prosthetics to pass as an old guy. The British actor and erstwhile model possesses an idiosyncratic beauty rooted in the slender angles of his visage, and as it turns out, these very facial aspects are what enable him to look simply incredible as someone you’d find in a retirement home.

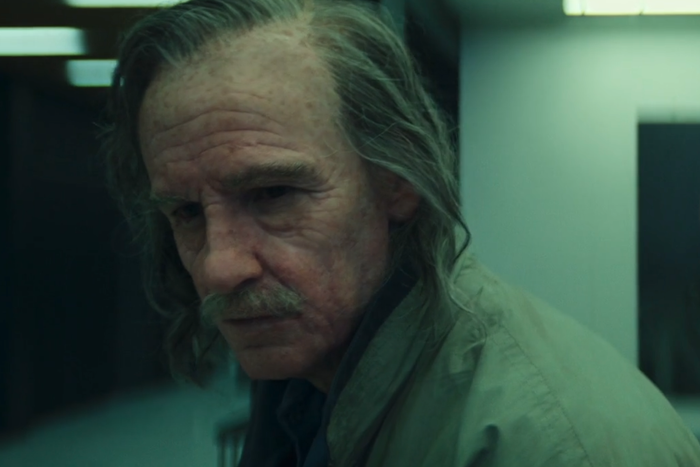

Consider Ralf the Janitor, whom the Jackal kills and impersonates in the Peacock and Sky series’ stellar opening sequence:

This introductory stretch sees The Day of the Jackal lay the foundation of its fundamental appeal. We follow the Jackal as he eerily embodies a crusty janitor who’s practically invisible to the rest of society in order to infiltrate an office building and shoot the son of a populist German politician. It’s pure competence porn: The Jackal puts on the prosthetics, smokes a cigarette to simulate the Janitor’s bad lungs, and shuffles his way up to the right floor. He’s very convincing, so much so that when his cover is blown and the Jackal proceeds to kill several people with alarming alacrity, the tension between Redmayne’s looking so very old and moving so very precisely produces unexpected hilarity — a quality deepened by how the show and the actor play the scene with dead seriousness.

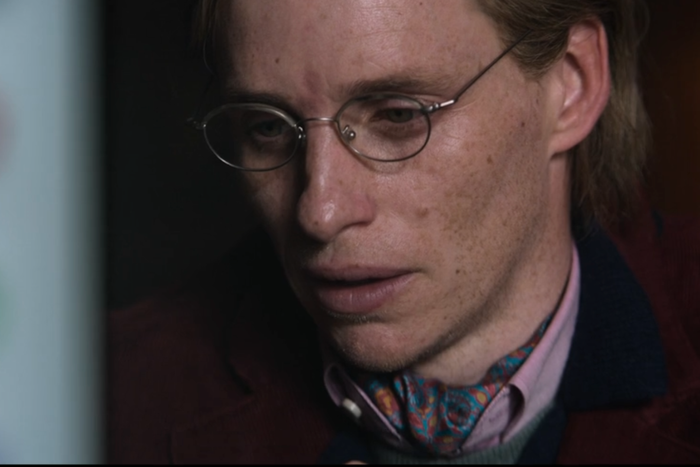

Such visual funny business recurs throughout The Day of the Jackal, which follows both the assassin as he’s contracted to make a major hit and an MI6 agent played by Lashana Lynch who obsesses over taking him down. At the top of the third episode, the Jackal assumes the role of some dead rich person’s brokenhearted progeny, visiting a high-end German funeral home to extract sensitive information from its computer system. The age this particular persona is supposed to represent remains ambiguous in the scene, but the Jackal uses a cane and maintains a sense of frailty in his body, both of which contribute to another visual iteration of geriatric Redmayne. Note the worldly age implied in his thousand-yard stare:

Is he a man in his 30s? 50s? 60s with dyed hair? Who knows. I’ll believe anything.

Redmayne’s work in The Day of the Jackal should not come as much of a surprise since the actor has long been drawn to physically transformative performances. Think back to a decade ago when we got a whole lot of Redmayne in one fell swoop: He won the Best Actor Oscar for playing Stephen Hawking, the British genius who suffered from Lou Gehrig’s disease, in 2014’s The Theory of Everything. The following year’s The Danish Girl saw his turn as Lili Elbe, the early-20th-century transgender landscape artist, in a performance that earned both criticism from the LGBTQ+ community and another Oscar nom. 2015 also saw Redmayne go full window to the wall as the villainous Balem Abrasax in the Wachowskis’ space opera Jupiter Ascending, in which he violently oscillates between aggressive whispering and yelling with every cell in his body. Sometimes in the same sentence! (“I CREATE LIFE!” he bellows at a mortified Mila Kunis, before dropping back down to a rasp, “… and I destroy it.”) Redmayne’s expansive thespianism has seemingly faded into the background in the years since, probably due to his leading turn in the Fantastic Beasts movies largely being memory-hole. But Redmaynia did briefly resurface earlier this year when his unhinged Cabaret performance at the Tonys drew widespread befuddlement, horror, and ambient arousal from millions of viewers. As with many of his previous performances, my boy Redmayne was done dirty.

If The Day of the Jackal hasn’t already turned Redmayne’s stock price around, it really should. The series is a rollicking watch despite being the third adaptation of the 1971 novel — following a critically acclaimed 1973 Fred Zinnemann film and a far lesser 1997 remake with Bruce Willis and Richard Gere — nobody really asked for. This version primarily functions as a modernization of the source material; instead of the Jackal being hired to assassinate French president Charles de Gaulle, as in the the novel and the Zinnemann film, the show sees the Jackal hired by Charles Dance’s British oligarch to take out a big-brained tech guy who threatens to overthrow the global elite by releasing a piece of software that would render all financial transactions transparent. (Don’t think about it too hard.)

Because of this modernizing impulse, The Day of the Jackal possesses a blended sensibility. Yes, it’s a thriller built on the pleasures of watching a guy with a gun efficiently doing stuff (as a 15-year-old boy at heart, I find it hard not to watch the Jackal’s clinical killing efficiency and not think, That’s kewl). But that’s juxtaposed with the sequences featuring Redmayne in old-man drag, which, while very convincing, are just so goofy they never fail to make me squeal with glee.

The pièce de résistance of the show’s prosthetics parade arrives in the sixth episode, when the Jackal poses as a very British septuagenarian, wheelchair and all, and shadows Lynch’s Bianca on a flight. (He even snags the seat right behind her!) Redmayne’s overt physical transformation here is interesting enough: Note the convincing liver spots and topographically ornate facial lines. But how the persona’s geriatric nature maps so perfectly onto Redmayne’s underlying qualities is what sells the package so well. The actor has a naturally soft, reedy voice that always sounds as though he’s wheezing a bit. The Jackal weaponizes it into a geezerly affect that extracts empathy. “Thank you so much, young man,” he murmurs to the airport attendant wheeling him to a cab. Redmayne’s British accent also possesses a discernibly patrician quality, adding subconscious layers to what passers-by might assume about this particular old man. Is he a professor emeritus at Oxford? Third-generation landed gentry? An accountant? The mind wanders but doesn’t ask too many questions. Such is a great disguise.

Not unlike Redmayne’s performance in Jupiter Ascending, the Jackal’s personae tend to oscillate between very big and very small. Redmayne is only truly transformative when he’s pulling off an old man; otherwise, he’s barely camouflaged. Late in the pilot, the Jackal poses as a rare-chess-set collector and it’s basically Eddie Redmayne in glasses. In the second episode, when he assumes the role of a duck hunter to meet a handler out in the wilderness, it’s Redmayne in nice outdoorsy layers. In the next installment, when he impersonates a chauffeur? Redmayne in a hat. These thinner disguises are theoretically interesting for the way they suggest that persons are largely conditional, i.e., identities congeal based on physical context, but that’s probably giving this series a bit too much credit.

In this week’s climactic episode, which sees the Jackal finally attempting the long-awaited hit on tech genius Ulle Dag Charles, the assassin adopts the identity of a vaguely middle-aged classical-music concertgoer in order to sneak into the venue. This is an example of The Day of the Jackal going way too small with the disguise. As you can see, the look is mostly Redmayne:

Sure, there’s some visual distinctiveness between the receding hairline and the large forehead. And Redmayne the thespian convincingly projects the sense of a well-to-do older man, leaning into his upper-crust accent as he complains about the price of all the concessions he’s purchasing. (He is about to hide in the rafters overnight, after all, so the guy needs food and drink.) But the costume is nowhere near as visually convincing, obscuring, or delightful as it could be. You know what would help? Add a couple more decades to that face, throw in a cane, and have Redmayne hunch over. Who’s gonna know?