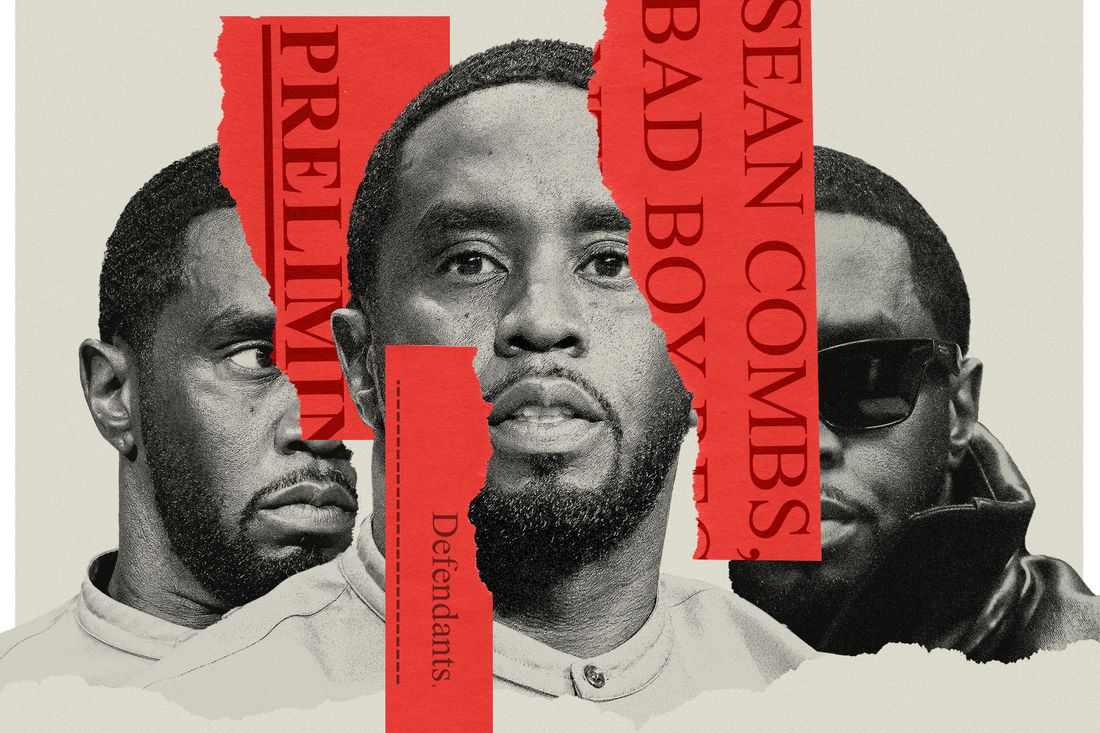

This article was originally published on April 17, 2024. Sean “Diddy” Combs was arrested in Manhattan on September 16, 2024, on charges that include racketeering conspiracy, sex trafficking by force, fraud, or coercion, and transportation to engage in prostitution.

A natural-born party promoter, Sean Combs could work any room. Chatting with hedge-fund manager Ray Dalio in 2019, Diddy broadcast a voracious hunger for knowledge, plying his mentor for career advice: “I don’t want to make the most money. I want to be known for giving the most money away.” Dropping into New York rap radio station Power 105.1’s “The Breakfast Club” amid a noisy return to music last year, he served liquor, talked about spirituality, and cracked “pause” jokes in quick succession. That disconcerting closeness of the cosmic and carnal was par for the course for Combs, an altar boy turned entrepreneur whose career is a monument to these and other striking dualities. His business empire blossomed across the ’90s and the early aughts in spite of jarring investigations into his enterprises and morals. He cultivated an affable, absurdist air offsetting his worst press, which in turn always tugged against his wholesome revamps. Now, as Combs fights an array of allegations of ghastly violence and sex trafficking that figure into a few different decades of his career, and endures FBI raids on his homes, how much of his public persona may have been a deliberate, face-saving con is becoming clear.

The Harlem native overcame profound adversity as a child when his father, an associate of legendary heroin kingpin Frank Lucas, was murdered in 1972, and his mother worked overtime to stay afloat. “One day we woke up,” the 54-year-old explained last year on Apple Music’s “Love Radio With Diddy,” “and there was so many roaches on my face and I was like, No, I’m not going to do that. I’m going to get out of here. I’m going to be somebody.” Combs earned the nickname “Puff” for his temper, which was also the impetus for his hip-hop empire. He made a splash organizing events at Howard University and sought out Uptown Records founder Andre Harrell when he returned to New York, but the relationship soured as the intern’s ambitions as an executive grew, sparking a split between Combs and Uptown that facilitated the foundation of Bad Boy Records in 1993 with Puff and the Notorious B.I.G. as its dynamic duo.

Biggie’s murder in 1997 punched a hole in Combs’s life and label roster and set off a brief but powerful reassessment of the pervasiveness of violence in hip-hop. Dancing through his pain while performing “I’ll Be Missing You” at the MTV VMAs in 1997, Diddy became an avatar for our distress. Fans bonded with him in grief, focusing less on accountability for the volatile coastal rap feud that had claimed the lives of Biggie and 2pac. By the end of the ’90s, with the launch of his clothing line Sean John, Diddy entered the same precarious entrepreneurial ascent as Jay-Z: They started small, founding businesses that succeeded at marketing a rapper’s cool to the masses, just as Run-DMC had parlayed a love of Adidas into music’s first sneaker deal. Combs’s fashion line, Sean John, offered fans a simulacrum of their shiny-panted icon’s velvet tracksuit at a more affordable price even as he dodged high-profile cases.

The fact of the matter is some people find a hip-hop heavyweight behaving like a crime boss alluring in the same way they hunger for gladiatorial strife between rappers. When Vanilla Ice claimed that Death Row Records founder Suge Knight shook him down on a balcony in the early ’90s, and when Jay-Z was accused of stabbing rap exec Lance “Un” Rivera in 1999, the hip-hop community viewed the incidents as evidence that those men would stop at nothing to get their way in a business relationship. This is our dance with Diddy, a general in hip-hop’s march toward mainstream dominance and corporate legitimacy between the ’90s and the aughts. His extensive track record of romantic hit songs is forever punctuated by a series of shocking scandals and matching feats of death-defying image reform. He seemed to resist the impression that he was Knight’s foil, and his plays to maintain control of this narrative have been illuminating.

“I felt like I disappointed the hip-hop community,” Combs told MTV’s Kurt Loder in 1999, after allegedly beating Nas’s former manager Steve Stoute with a Champagne bottle and a telephone. He continued, “Because everything I do I’m trying to be a team player in taking hip-hop to the next level.” After initially denying the allegations, he pleaded guilty to a reduced harassment charge and was ordered to serve one day in an anger-management program. Before the year was out, though, Combs, then-girlfriend Jennifer Lopez, and Bad Boy rapper Shyne were in jail following a nightclub shooting that left three people injured a day after Christmas. (Lopez’s charges were dropped.) Combs was acquitted on gun-possession and bribery charges — prosecutors had unsuccessfully argued that he wanted his bodyguard to take his weapon — and Shyne spent much of the aughts in prison before he was deported to Belize in 2009. “His lawyers were there to secure a ‘not guilty’ verdict by any means,” Shyne explained in 2022 on Queens rapper NORE’s podcast, Drink Champs, a tentpole of Diddy’s Revolt network. “He’s a $100 million corporation, and they looked at me as the enemy.” Combs retired his “Puff Daddy” moniker after the trial.

Puff’s pivot to P. Diddy propelled a shift in public opinion in 2001. He ditched the kingpin aesthetics of early music videos, pointedly golfing in the suburbs in “Bad Boy for Life.” (He originally intended to bounce back with a gospel album, beating R. Kelly to the spiritual-reputation-reform campaign of U Saved Me by three years.) His talent-search shows, Making the Band and Making His Band, demonstrated the veteran producer’s eye and ear for a successful singing group while revealing a taskmaster’s self-importance. Diddy joked about having Bill Clinton appear at a name-change ceremony in 2001, and by 2004, he was urging fans to “Vote or Die!” He chased after the trappings of the well-rounded 21st-century man and catered to the interests of the politically savvy class of Bush-era millennials. This eased Combs into a respectable-elder-statesman role as his attention shifted from albums and songs charts to boardroom plays. He’d become something of a totem for the ambitions of a generation of Black creatives. If this inner-city dreamer could sell singles, clothes, vodka, movies, and soul food, the sky would be the limit for his successors.

Mainstreaming Diddy’s persona worked because admirers of his aspirations needed the hero. The fleeting success of notable Bad Boy signees — like Ma$e, Craig Mack, Total, and Shyne — couldn’t sink the label head’s reputation for cultivating talent; that revolving door of artists in did not arouse enough suspicion. We never quite stopped hearing wild whispers and often suspected something was going on with Cassie Ventura, the Connecticut-raised R&B singer Combs met in the aughts while she was working on a debut with singer-songwriter and producer Ryan Leslie. Ventura released a self-titled album in 2006 and then seemed to the uninformed observer to speed off into a life of jet-setting with Diddy to the detriment of her singing career. Ventura filed suit this past fall thanks to New York State’s Adult Survivors Act, which allows victims to sue beyond the usual statute of limitations. What Ventura alleges is more harrowing than anything in the years of cavalier gossip-page and forum rumors about the pair: grievous harm and mortification even as Diddy made bubbly late-night and daytime television appearances on Jimmy Kimmel Live and The Ellen DeGeneres Show. The scale of Diddy’s alleged double life is breathtaking. (Diddy has denied all her allegations.) Rapper Kid Cudi corroborated Ventura’s accusation that Diddy blew up his car following a rumored beef over Ventura, tidbits of which spilled into gossip headlines in 2012.

The generation weaned on the Uptown and Bad Boy classics navigated such strife with belittling humor, treating Cassie like a musical flash in the pan with an inexplicable hold on the more powerful men around her. Her lawsuit — settled in a business day with a reminder that doing so is “in no way an admission of wrongdoing” — should spark a wave of soul-searching about the outsize importance of power players in hip-hop and the sense that the people around them are merely pawns in a struggle to advance culture.

What sets Diddy’s flurry of cases apart from the reckoning of an R. Kelly, whose involvement with teenage girls was somewhat public knowledge more than a decade before it became somewhat unpopular to play his music outside, is how it feeds an ongoing moral panic. Tales of dark misdoings at clandestine parties excite the imagination of a world perpetually on the hunt for logs from Jeffrey Epstein’s island, one that gorges itself endlessly on true-crime media. The hip-hop community unafraid to object to LGBTQ people merely existing is not acting in defense of Lil Rod — a musician brought in to work on Diddy’s 2023 comeback album, The Love Album: Off the Grid, whose bombshell February lawsuit accuses Combs of covering up a shooting and engaging in a grueling pattern of same-sex assault (both of which Diddy denies) — when it cracks homoerotic Diddy jokes.

“No Diddy” is a garish bit of comeuppance that wrenches the significance of the name back from a man who has redefined his nom du rap repeatedly over the years, recontextualizing it into an update on the “pause” game. It manages the double whammy of playing grisly accusations of abuse up for yaks while otherizing already long-suffering queer hip-hop fans by restoring a glimmer of the unrepentantly homophobic 20th-century version of the culture, when slurs and hateful rhetoric were (more) commonplace. It’s an inelegant nonsolution, a misguided mass uncorking of the most macabre humor reflex. It models the inability of the industry to disseminate a clear-eyed response to the gravest news. In the fallen, gutted hip-hop press of this decade, beset by merchants of misinformation, the closest it seems we might get to a reassessment of Diddy in the short term is this deluge of jokes about latent homosexuality circulating among everyone from zoomer streamer king Kai Cenat to veteran frenemies 50 Cent and Ma$e. A scene that processes sex-trafficking accusations with a hail of puns, of course, remains a playground for anyone in a position of power who is accused of partner abuse. Domestic violence and sexual-assault accusations don’t curb feature requests and festival spots in this climate. It’s the good time you provide that’s most important.

It’s tough to telegraph the future of the many-named mogul, to know what the FBI is looking for, to figure out what to make of the handcuffing of his sons and the sexual assault allegation that Christian “King” Combs is now fighting, and to predict what listeners would do with the vast catalogue of music Diddy touched if he ends up in prison. We can ditch our attachment to the all-knowing, unflappable business impresario as a concept, while its stock continues to plummet, or we can party and bullshit our way through this time pretending we rooted out a batch of bad apples, only to come together in another five years surprised when it happens again. Joking about the lasciviousness of Diddy’s parties now that it is socially acceptable to take such umbrage doesn’t change the reality that it wasn’t so long ago that many would walk through fire for an invitation. The urge to throw someone under the bus without dismantling the infrastructure upholding abuses of power is the allure.

Diddy’s lifestyle empire seems to be coming apart, as orbital partnerships with companies like Revolt and Hulu, which had been working on a reality show starring the Combs family, disintegrate like space junk reentering the atmosphere. The flame of fearful and corrective disassociation burns hot and clean. These fast moves —and all the high-profile infighting by sometime Diddy associates caught in the maelstrom of suspicion and misinformation like Meek Mill and Yung Miami of the City Girls — reveal an industry most interested in damage control, in dropping excess cargo and peeling off into the future. We cannot continue on as before, though, teaching another generation to seek the slapstick in sex crimes and revel in conspiratorial thinking. We can’t keep picking and choosing whose abuse we’re willing to buy, turning support for survivors into a contest of whose abusers made the most beloved songs. We can’t let wealthy men treat everyone in the vicinity like chattel. There is no hit single worth degrading and violating another human being; hip-hop is 50 and old enough to know it.