Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the October 7, 1991, issue of New York. We’re republishing it to mark the release of The Disney Dilemma, the latest season of Land of the Giants from Vulture and the Vox Media Podcast Network.

“You’re 60 days early,” Jeffrey Katzenberg said.

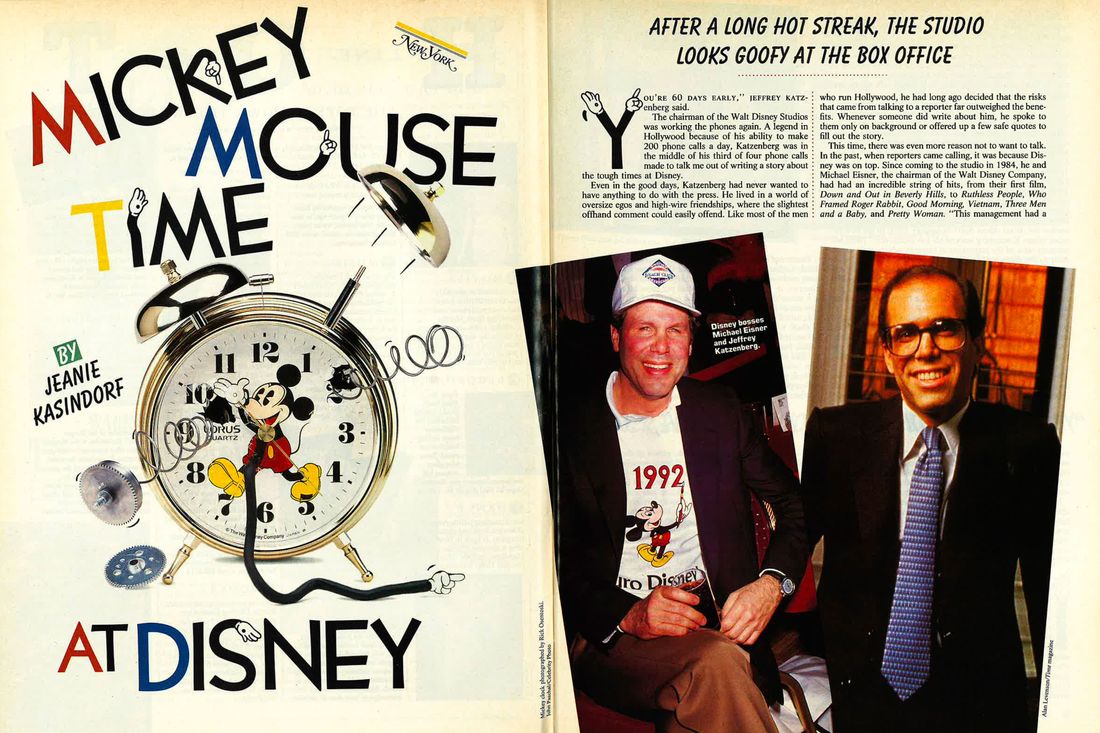

The chairman of the Walt Disney Studios was working the phones again. A legend in Hollywood because of his ability to make 200 phone calls a day. Katzenberg was in the middle of his third of four phone calls made to talk me out of writing a story about the tough times at Disney.

Even in the good days, Katzenberg had never wanted to have anything to do with the press. He lived in a world of oversize egos and high-wire friendships, where the slightest offhand comment could easily offend. Like most of the men who run Hollywood, he had long ago decided that the risks that came from talking to a reporter far outweighed the benefits. Whenever someone did write about him, he spoke to them only on background or offered up a few safe quotes to fill out the story.

This time, there was even more reason not to want to talk. In the past, when reporters came calling, it was because Disney was on top. Since coming to the studio in 1984, he and Michael Eisner, the chairman of the Walt Disney Company, had had an incredible string of hits, from their first film, Down and Out in Beverly Hills, to Ruthless People, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Good Morning, Vietnam, Three Men and a Baby, and Pretty Woman. “This management had a track record that is awesome, awesome,” says Wall Street analyst Manny Gerard of Gerard Klauer Mattison & Co. “These guys were unbelievable.”

Where they arrived, Disney was in last place among the Hollywood studios with only 3 percent of total box-office revenue. By 1988, it had moved to first place with more than 19 percent of the total box-office take. Disney and Katzenberg had done it in part by using the Disney Method: Talk tough, talk cheap, and keep total control. And it worked miracles.

The Walt Disney Company’s earnings went from $98 million in 1984 to $824.5 million in 1990. The profits came not only from the film division but also from the Disney theme parks, the Disney Channel, hotel and real-estate ventures, and Disney consumer products. By the end of the ’80s, Michael Eisner and Mickey Mouse had graced the covers of Time, Newsweek, and BusinessWeek.

Then, in 1989, the film division started to go cold. After a long slump, it was saved by Pretty Woman. But by the fall of 1990, things had started to cool down again. In the past 12 months, the studio has had several debacles (among them The Marrying Man and V.I. Warshawski), two disappointments (Three Men and a Little Lady and The Rocketeer), and only one modest hit, What About Bob? In January 1991, in his now famous memo, Katzenberg warned his top executives, “There are ominous signs of the stagnation of Maturity which leads inexorably to the disaster of Decline.”

“It’s no longer ‘We got unlucky; the pendulum caught up with us,’” says Manny Gerard, who as long ago as January 1990 warned his clients about the Disney film division. “This is a total breakdown of the system. This is a tragedy we’re talking about here.”

It was a tragedy that Eisner and Katzenberg did not want to discuss right now. “I am changing the direction of what we’re doing,” Katzenberg said. “It’s been on track for nine months and it’s all coming together, and you want me to whip it out before it’s taken form.” He would discuss his plans on background, he said, if I waited another five to eight weeks.

Not believing for a second that the conversation would take place, I told him I was going ahead with the story. “It is not possible, in my opinion, for you to do the story by jumping on it overnight,” he said, trying to convince me that writing the story would be bad for me. (“I learned that from him,” one former Disney staffer said after I described the conversation. “The trick is to make people feel you’re thinking of their own interests, that what is in his best interest is also in your best interest.”)

If I insisted on going ahead, Katzenberg said, I would not be able to talk to him or Michael Eisner. “I can tell you Michael’s too good a partner to talk to you in a story where I’m not going to talk to you,” he said. He was still unfailingly polite, but now there was a slight edge to his voice. “If you are doing it by jumping on it overnight, then go ahead. Talk to a lot of producers and writers and directors. Have fun.”

In the fall of 1984, Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg arrived at the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California, where a portrait of Mickey Mouse decorates the white water tower that rises over the sprawling San Fernando Valley lot. They had come from Paramount Pictures, where both had spent a large chunk of their professional careers. Eisner, 49, had put in eight years there as president of Paramount Pictures under chairman Barry Diller, who is now chairman of Fox, Inc. Katzenberg, 40, had spent ten years there, starting out in 1974 as Diller’s assistant and, by 1982, becoming Eisner’s production chief.

Eisner and Katzenberg came to Disney with firm ideas about doing business in Hollywood — ideas that came in part from their professional experience and in part from their personal histories. In 1981, Michael Eisner had put those ideas on paper in a memo that he wrote (with some polishing from production executives Jeffrey Katzenberg, Don Simpson, David Kirkpatrick, and Ricardo Mestres) to Charles Bluhdorn, the chairman of Gulf + Western, which owned Paramount. Around Paramount, it became known as the Paramount Philosophy Paper.

Rule No. 1 of the Paramount Philosophy was “high concept,” or “The idea is king.” Diller and Eisner first coined the phrase high concept — the notion that a movie should be able to be described, and sold to the public, in one short sentence. It was a philosophy they learned in their years at ABC, where Diller, the vice-president of prime-time television, and Eisner, the head of prime-time programming, invented the movie of the week and the miniseries. There you had to be able to promote a show in between commercials in 30 seconds or less.

Rule No. 2 was “Get them cheap.” “Michael believes you should get people when their careers are just starting or are stalling, rather than overpay people who are already there,” says one former Paramount executive. “At Paramount, he learned from Diller how to hire everyone on a film himself rather than paying huge fees to agents who package movies. Keep in mind he’s a rich kid who doesn’t believe in spending his or anybody else’s money. It’s really out of Our Crowd.”

Eisner, who attended the exclusive Lawrenceville School before going on to Denison University in Ohio, grew up on Park Avenue, where his parents made him wear a jacket and tie for dinner. Eisner’s grandfather was one of the founders of the American Safety Razor Company, which he and his parents sold to Philip Morris. Another grandfather became wealthy running a clothing business that manufactured uniforms and parachutes for the Army. Eisner’s father, Lester, was a lawyer who invested in New York real estate.

“I was brought up to believe that money is not frivolous,” Eisner once told Tony Schwartz (New York, July 30, 1984). “My grandfather drove across the Willis Avenue Bridge to save the toll. My father believed I should know what I had, but one of the lessons I learned was that you do not spend capital. The idea of responsibility with other people’s money stayed with me, particularly in this industry, where you’re up against people who discount the value of other people’s money.”

Rule No. 3 of the Paramount Philosophy was “Keep control.” In the ’70s and ’80s, Paramount gained a reputation for being a studio that tried to make your movie for you. “It starts with Michael,” says one former Paramount producer. “Michael is one of the biggest f—ing control freaks you’ll ever know.”

It followed through with Katzenberg, who learned the business from Diller and Eisner. Katzenberg, the son of a stockbroker, was raised on Park Avenue only a half-block away from Eisner. At the age of 14, he became a volunteer in John Lindsay’s mayoral campaign. After graduating from Fieldston, he spent a year at NYU, then dropped out to work in City Hall. In the early ’70s, he left politics for show business. He worked briefly as an agent and as an assistant to producer David Picker before finding a home at Paramount.

Katzenberg learned to run a studio so that every decision — no matter how minor — eventually had to come up to him. At Disney, he hired two executive vice-presidents. He brought Ricardo Mestres over from Paramount. Mestres, 33, whose father is a partner at the New York law firm Sullivan & Cromwell, is another well-to-do New Yorker who went to Buckley, Exeter, and Harvard. Despite his upper-crust upbringing, he was hired out of Harvard by Don Simpson under a minority-hiring program at Paramount. Katzenberg also brought in David Hoberman, a former ABC Radio president who created the talk-radio format. But Hoberman and Mestres were given little leeway to make final decisions. Production vice-presidents say that after signing on at Disney, they quickly discovered that they were mere messengers carrying information from filmmakers up through Hoberman and Mestres to Katzenberg and then back down again.

“I think Jeffrey has always been a control freak,” says a former Paramount executive. “I think it was always in his nature, absolutely. His office at Paramount gave you a clue. It was all white, blindingly white, with nothing on the desk but one blue felt pen and one black felt pen and his index cards with ‘to do’ lists.”

Rule No. 4 of the Paramount Philosophy, which would never find its way into a memo, was “Work the staff at Katzenberg’s manic pace.” Then, if a wonderful project suddenly appeared, you would be the first studio to find it (at Paramount, Katzenberg was nicknamed “the Golden Retriever” for his ability to bring in projects). The “What Makes Jeffrey Run” stories are legend: how he could be found in his office at six every morning, including Saturdays. How he could squeeze his 200 phone calls plus two breakfast meetings, a lunch meeting, and a dinner meeting into every day.

“On a regular day,” says one former production executive, “I’d be there by 7 a.m., and unless I had a business dinner, I’d leave at 8:30. On Saturday I’d work from nine to six and on Sunday from noon to five. It was kind of an unwritten rule that you had to come in and do your reading there. At other studios, the production executives read their scripts at home. But there was the idea that if you read something and liked it, you had to be there to tell someone. You had to be on call like a little slave. There wasn’t a day I never felt panicked.

“You become so insulated. You never see your family. You miss those essential components that you need to figure out what good stories are all about. Jeffrey hasn’t seen his twins growing up; he has missed all that. He was there at six in the morning, at seven on Sundays. On Sundays he would take a break and take his twins to breakfast, then come back to the studio.”

Chris Zarpas, one of the presidents of Island World LA, was hired by Katzenberg as a production vice-president in 1987. “Jeffrey called me for my job interview in his office at 7 a.m. on a Sunday,” he says. “There is one story I’ll never forget that typified the time I was at Disney. I had to write a development memo for a Friday meeting. It was Wednesday at 10:30 p.m., and I was in my office furiously working away, and Ricardo Mestres walked by. I said, ‘I’m kind of panicked. I’m having a terrible time.’ He looked at me very gravely and with absolute seriousness, he said, ‘Chris, let me give you some advice. Your brain’s about to shut down. Work until midnight, go home, get some sleep, come back at four in the morning.’

“But this is very important,” Zarpas continues. “I look back on that story with the utmost affection for the place. Because I was never asked to do anything that they wouldn’t do themselves. Jeffrey Katzenberg works harder than anyone I’ve ever met in my life. There was a time Jeffrey called me for a meeting with a director on a Sunday that lasted ten minutes, when he knew I had 50-yard-line tickets to go to the Super Bowl. People say, ‘What an assh—,’ but I don’t look at it that way. I was a kid in Washington distributing little art films, and I was given the opportunity of a lifetime.

“And I learned how to make a movie. I was hired away by a company paying me a lot of money and giving me enormous latitude in making decisions because I have the Disney cachet. I look back as one who made a career out of the Marine Corps might have looked back on boot camp. It was treacherous; it was hard; it was horrible at the time. But I was given the education of a lifetime.”

There has always been an ongoing battle between studio chiefs and filmmakers over who gets to make a filmmaker’s film. With the Disney Method, Eisner and Katzenberg raised that battle to high art. “You know about a ‘hands on’ experience?” quips one producer who used to make movies at the studio. “Making a movie for them is a ‘hands in’ experience.”

It starts in the pitch meeting. “Most studios just sort of listen to you and get the gist of what you want to do,” one screenwriter says. “At Disney, they want to know every single detail; they want to take as much spontaneity out of the process as possible. They write down every word you say it’s like giving a deposition — you feel like you’re testifying. And they are obsessed with details that don’t matter. You’d pitch Lawrence of Arabia and they would want to know what color shows he would be wearing.”

The Disney Method continues in the contract negotiations. The studio tried to get writers, directors, and producers cheap and then sign them to multi-picture deals. “The whole tenor is ‘Let’s go beat them up,’” one former production executive says. “They disregard everyone’s previous quote. It’s unheard-of. If a writer says, ‘I made $70,000 for a screenplay at Fox,’ they say, ‘We don’t care; you deserve $60,000.’”

The legal-and-business affairs department is run by a lawyer named Helene Hahn, whom Eisner and Katzenberg brought over from Paramount. She soon became known around town as “Attila the Hahn.” “There is an absolutely arrogant attitude among Helene Hahn and all her people,” says one agent. “She is, in a way, Jeffrey’s hit man. There always been a give-and-take in negotiation, but with her there is the attitude ‘Excuse me, take it or leave it.’”

Once the contract negotiations are concluded, the real fighting begins. There are endless meetings about the script, and an endless number of production memos. “All the studios do it to some degree,” says a former executive. “But at Disney, they got carried away. It started off as a methodical way to respond to screenplays and ended up being a real kind of dogmatic piece of communication. ‘On page 33, we don’t think Charlotte should use the words “Mom died.”’ Basically what it was saying was ‘Jeffrey’s not going to make this movie with those words in it.’”

In one preproduction meeting that has become a legend on the Disney lot, a director’s blood pressure rose so high that his doctor ordered him not to make the movie. Stuart Gordon was meeting with David Hoberman about Honey, I Shrunk the Kids when his nose started to bleed because of his blood pressure. “My doctor said, ‘I think you have to make a decision of whether you want to make this movie or want to live,’” says Gordon, who despite the experience is now the executive producer of the sequel, Honey, I Blew Up the Baby, for Disney. “But I don’t think you can lay it on David. Part of the problem was I was coming off another film and had had no break. Although the Disney people are the toughest guys in town, I think it’s typical of prepping almost any movie.”

Once the shooting starts, the Disney executives still keep close control, often stationing young executives on the set with cellular phones. On The Marrying Man, crew members distributed T-shirts showing a bar slashed across the picture of a monkey talking on the phone.

Business Week writer Ron Grover, in a book called The Disney Touch, tells of how director Garry Marshall stormed off the set of his first Disney picture, Beaches. “They come in and make you crazy,” said Marshall, who went on to direct Pretty Woman. “I wasn’t going anywhere [when I walked off the set]. I just went into my act. Pretty soon, everyone is so worried that you’ll leave that they leave you alone.”

Joe Johnston, who directed Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and The Rocketeer, says he won’t work for the studio again. “They took me because I hadn’t directed before and I was cheap. They do that, then they like to think they can push you around. You can make your own movie, but you have to stand firm. I even had to have one of the young production executives thrown off the set once. The truth is you will only get respect from them if you are tough, and the tougher you are, the more respect you’ll get. If you get Jeffrey in a room and called him all the worst names you could think of, you’d get his most respect. It’s so twisted, it’s so bizarre.”

Over the past seven years, it has become a cliché in Hollywood to say you won’t work for Disney. “They’ve been calling me about a project that they’re really anxious to do,” one producer says. “The answer is ‘I’m too old and too rich to deal with the s—,’ What they do is they totally dispense with producers. Then, in postproduction, they tend to dispense with directors by simply doing it their way. There is a very limited number of able directors and able writers, and they don’t go there, because they become functionalities.”

Yet for all the complaining, there are still plenty of people who say they have no trouble working within the Disney system. Marty Kaplan, a former Mondale speechwriter who is a writer-producer at Hollywood Pictures, says, “There’s a difference between the studio having a point of view and fighting for it and being a dictator. The fact that the studio has a point of view is something someone should be grateful for. The rough and tumble of ‘I hate this; I love this; don’t do that,’ there’s the reality of living inside Disney, and some people don’t have the stomach for that. Some people think that’s an inappropriate way to conduct business. I still don’t. I guess you just have to want to fight for what you care about. In a business that’s totally subjective, it’s not such a bad thing that to have anything happen requires spilling some hormones.”

Robert Cort, who with his partner, Ted Field, had produced Outrageous Fortune, Three Men and a Baby, and Three Men and a Little Lady, says, “There’s a continuum among studios from totally laissez-faire, to the point where you wonder how someone could give over so much money with so little oversight, to totally hands-on. And they’re at the end of it. They are an enormously hand-on group of executives. That’s the corporate mentality.

“A lot of this has to do with your expectations. If you’re expecting someone to say, ‘Hey, go make your movie,’ that’s certainly not the place to be. Because they are forceful, you have a lot of arguments with them. Listen , I grew up in a family where you argued. It’s not the most painful thing in the world. Given the choice, we would prefer to be with the hands-on type. A lot of good things come out of it.”

Even once the picture is finished, Katzenberg never lets up. “Jeffrey basically ran the marketing and distribution departments as well,” one former Disney marketing staffer says. “In the marketing meetings, they would play a TV spot or a rough cut of a trailer, and almost before it was finished, Jeffrey would say, ‘That’s a good start, but look, the music cues, you’ve got to open here, and the opening image should be at the end. Now, here’s what you need at the beginning: Move that image from the middle, and guys, lighten up the music; okay, now.’ I would never be able to be that single-minded about my business, ever. Some say that’s pathological; some say it’s the mark of a good executive.”

For six years, that system gave Katzenberg and Eisner a remarkable run of successes. They created the Disney formula film — an urban, adult comedy starring easy-to-get-for-a-good-price television and movie stars. It was a strategy that Katzenberg called bottom fishing, and the box-office dollars started pouring in.

Their first film, Down and Out in Beverly Hills, starring three down-on-their-luck actors, Bette Midler, Richard Dreyfuss, and Nick Nolte, was made for only about $14 million and took in about $62 million from U.S. and Canadian box office alone, or about $34 million in actual film-rental revenue that the theaters return to the studio.

Even more dramatic is the story of Pretty Woman, Disney’s biggest box-office hit. Katzenberg bought a script called 3,000, a dark story about a softhearted prostitute and a heartless businessman. Disney hired Garry Marshall, a successful film director who had created the television comedies Laverne and Shirley and Happy Days when Katzenberg and Eisner were at Paramount, to turn it into a comedy. Disney made the film for $17 million (paying Julia Roberts only $350,000).

It took in $178 million in U.S. and Canadian box office, or $98 million in actual film-rental revenue that the theaters return to the studio. (Runaway hits return about 55 percent of the box-office take, moderate hits return about 45 percent, and flops return about 35 percent.) It then took in about $50 million in foreign theatrical release and another $90 million in the sale of videocassettes. According to Art Murphy, the box-office analyst for Daily Variety, those three markets represent 50 to 60 percent of the revenue that a successful film will bring in over five to seven years (from world box office, home video, pay television, network television, cable television, and television syndication). That means the total revenue the studio will take in is $396 million to $476 million — minus its original $17 million investment, the $20 million or more it spent on distribution, the interest on those funds, and whatever share of the profits was promised to the stars or filmmakers.

From 1984 to 1990, the Walt Disney Company’s earnings exploded exponentially. The Disney Studios contributed to that with more than their new box-office hits. They also brought in big profits by releasing films from the Disney film library on videocassette and selling them to the Disney Channel and other cable outlets. And they accelerated the rerelease of animated classics like Lady and the Tramp from every seven years to every five years.

They have been well rewarded for turning the company around. This year, Michael Eisner, who lives in Bel Air with his wife and two sons (a third son is in college), will take home a $750,000 salary plus a $10.4 million bonus. Jeffrey Katzenberg’s contract is not a matter of public record. But it earned him enough to provide him and his wife and 8-year-old twins a house on Carbon Beach in Malibu and a Nouveau Mediterranean mansion in Beverly Hills.

By the winter of 1988, Eisner and Katzenberg had decided to use all the new money that was flowing in to the company to finance even more movies. They announced that in addition to their existing movie labels, Touchstone Pictures and Walt Disney Pictures. They hoped that eventually the new label would produce ten to 12 pictures a year, almost doubling the number of pictures coming out of the Walt Disney Studios — and doubling the company’s profits.

So far, it hasn’t worked out that way. In 1989 and the beginning of 1990, Disney went through a long slump, with films like Cheetah, An Innocent Man, Gross Anatomy, Blaze, and Where the Heart Is. The studio fell to fourth place in the 1989 box-office ranking. At the same time, it was being forced to pay more for talent, both because of rising prices in Hollywood and because the down-on-their-luck actors it had hired for its early films had become high-priced stars.

In the first half of 1990, Disney’s box-office figures rose dramatically because of Pretty Woman, Arachnophobia (which took in $53 million in North American box office, or about $24 million in film rentals), and Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy (which took in $104 million, or about $57 million in film rentals). But Arachnophobia, which the studio had hoped would be a $100 million hit, was a disappointment — in large part, many thought, because of a botched marketing campaign. And Dick Tracy exacted a different kind of price. Suddenly, a studio that had been knows for its ironclad control had allowed had allowed a film to run out of control. The movie cost that studio $46.5 million to make. Even worse, according to figures obtained by Daily Variety, it costs $54.7 million to distribute. The $54.7 million included $48.1 million spent on advertising and publicity to try — unsuccessfully — to beat the record that Warner Bros. had set with Batman the year before.

Then came the fall of 1990. It started with two flops, Taking Care of Business and Mr. Destiny. They were followed by two disappointments. Rescuers Down Under, the animated film that was supposed to be this year’s Little Mermaid, took in only about $12 million in film rentals compared to about $46 million from Mermaid. Three Men and a Little Lady took in about $32 million in film rentals compared to about $92 million from Three Men and a Baby. “Both Rescuers and Three Men and a Little Lady ran into a buzz saw called Home Alone,” says Wall Street analyst Manny Gerard. “It went after their audience, and it just buried them. ’Cause every kid in America wanted to see Home Alone 63 times.”

Disney had moderate successes in Green Card and White Fang. Then things got dramatically worse with films like Run (which took in about $1.5 million in rentals), Scenes From a Mall (about $3.4 million), One Good Cop (about $5 million), and Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken (about $2.5 million).

In April, the company released The Marrying Man, the film that Premiere magazine dubbed the “production from hell.” It was originally budgeted at $15 million, ended up costing about $26 million, and took in only about $4.5 million in rentals. But even worse than the financial loss was the psychic loss. For the second time in less than a year, the studio had a film that was out of control. It had taken an inexperienced first-time director and put him in charge of a project with two volatile stars who fell in love on the set. Midway through shooting, the studio had to threaten to sue Kim Basinger is she caused any more slowdowns. In May, it had its one solid hit of the year, What About Bob? (about $28 million in rentals).

Then came summer. The recession finally hit the movie business as theater admissions dropped to their lowest level since 1974. There were only three big summer hits — Terminator 2 ($191.5 million in North American box office, or about $105 million in film rentals), Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves ($156 million or about $86 million in film rentals), and City Slickers ($116.4 million or about $64 million in film rentals) — and none of them belonged to Disney. As with Three Men and a Little Lady, the studio had pinned high hopes on The Rocketeer. It had cost about $40 million to $45 million to make, and it took in about $21 million in film rentals. “The Rocketeer thing really was a marketing debacle,” one insider says. “They made every 14-, 15-year-old buy think it was a baby movie and completely missed their teenage audience.”

The Rocketeer was followed by V.I. Warshawski, the Kathleen Turner film that became a Hollywood laughingstock. It cost about $17 million and took in only about $3.7 million in film rentals. It was followed by The Doctor, the studio’s one critical success of the year, which cost about $19 million and could eventually take in $18 million in North American film rentals. Although some of these films will make money for the studio after a five-to seven-year run, the way everyone in Hollywood judges a hit is by how well a film has done in its North American run. And Disney films aren’t doing well anymore.

Hollywood Pictures accounted for an embarrassing string of those films — Taking Care of Business, The Marrying Man, One Good Cop, Run, and V.I. Warshawski. That added up to five off its first six films. The rumor mill around Hollywood started speculating about how long Mestres would be in his job. But no one who knew Eisner and Katzenberg well believed they would remove him. “This is a group of people who are very loyal,” one former Disney insider says. “by giving up on Ricardo, Jeffrey would be admitting that he was giving up on himself.”

101 Explanations

Why the Disney Magic Stopped Working

So what went wrong? Hollywood is a place where there are almost as many theories about how the business works as there are unsold screenplays. Here are the most popular theories about what has gone wrong at Disney:

.

Nobody Knows

First coined by screenwriter William Goldman, the theory is that since nobody really understands what the audience wants, all studios will inevitably have their good times and their bad times.

“I really don’t want to be anywhere near this,” says a producer. “But take a look at the movies that come out at Paramount after Eisner and Katzenberg left. It was as bad a year as they’re having now.” Indeed, the list bears him out. In 1985, following som every successful years, the studio released a particularly unmemorable roster of films: Clue, D*A*R*Y*L, Explorers, King David, Macaroni, Rustlers’ Rhapsody, Stephen King’s Silver Bullet, Summer Rental, That Was Then … This Is Now, Young Sherlock Holmes. The only notable films on the list are Compromising Positions and Witness. “Michael and Jeffrey don’t talk about that,” the producer says. “They neatly escaped it. So this is not ‘Oh, my God, how did this happen to us?’ It happened before, it will happen again.”

.

Skinning the Cat

“They made pictures to a formula that wasn’t an obvious formula in the beginning,” says Wall Street analyst Manny Gerard. “Now it’s an obvious formula. They skinned this cat every way it can be skinned.” A former Disney producer says, “I’m on my way deep background here, but I think it’s a good thing what happened to Disney, because it proved no formulas work. It can work for a little while, as then the audience is exhausted and you have to change. People are responding to quirky movies with unsympathetic heroes, stories that even have unhappy endings. And this is a lesson for everyone.”

.

Nickel-and-Diming

This is one of the two theories that presuppose that there is divine retribution in Hollywood. “It’s karma for killing people in deals,” says one producer. “There’s a way in which you get punished for going for the extra dime, for saying, ‘Screw you, plus options on your next six pictures,’ ‘Less money than your last screen plus your first child.’”

The proponents of this theory love to point to the debacle of The Marrying Man, where Jeffrey Katzenberg hired an untested but cheap young director to handle tow difficult stars like Kim Basinger and Alec Baldwin. “It’s insane; it’s not wise,” says another executive. “Where Michael Eisner is always flawed is that for him its axiomatic that you can’t buy more quality with more money.”

.

Talking Back

This is the second of the divine-retribution theories, which holds that their bad year is punishment for all those pages of production notes that tell a filmmaker how to make this film. “If you look at the big successes at Disney,” says one former Disney staffer, “they have always been where they weren’t able to intrude as much with a director. Peter Weir in Dead Poets Society, Bob Zemeckis in Roger Rabbit, Garry Marshall in Pretty Woman, Barry Levinson in Good Morning, Vietnam. With the exception of Three Men and a Baby and Cocktail, their biggest films had very strong, very opinionated guys directing them.”

Proponents of this theory love to point to Randa Haines, who directed The Doctor. The studio wanted the film to end with the comic scene (completed with a visual gag about enemas) where the doctor turns his interns into patients. Haines wanted to end it with the dramatic scene on the hospital roof where the doctor reads a note from a fellow cancer patient who has just died. “Their ending tested a couple of points better,” she says. “And I really searched my soul a lot and felt I could not sleep at night if I made those changes. And Jeffrey heard me say that and, without any malice at all, said, ‘Finish your movie.’”

.

Beep, Beep, Beep

“Their marketing sucks,” one former Disney staffer says. “They do everything in house, which is cheap but stupid.” All over town, producers, directors, agents will tell you that Disney needs to find a new way to market its movies. “They have the same trailer for all the films with the same pattern,” says a studio executive. “They tell the whole story — beep, beep, beep — with that same announcer’s voice Jeffrey likes. It’s just stale; they should shake it up and invigorate it.”

.

Movies, Movies, Movies

This theory is predicated on the notion that they should never have increased the number of movies they were producing. “When they started Hollywood Pictures, I asked them one question,” Manny Gerard says. “‘How do you increase the units of production and maintain quality?’ I still haven’t gotten an answer.”

One studio executive says he could have told them that from his own experience. “There’s a dirty little secret in this town,” he says, “which is that there is always too much money and not enough talent. There is such a dearth of talent when it comes to writers, directors, and producers that its frightening. And when you increase your output in production in proportion to your ability to finance movies, you will fail. Until you have done it, you don’t know how hard it is.”

.

Too Much Jeffrey

“They have extremely good people in David and Ricardo,” says one producer. “They ought to give them more power. Let them go with their instincts in a lot more cases. That will take care of the problem they have with filmmakers, because those people are more influenced by the filmmakers. But if everybody has to go up to Jeffrey on every little decision, what comes back is not what they believe is right but what they believe Jeffrey believes is right. Which isn’t always right, because Jeffrey can surprise you a lot of time.”

.

Too Little Jeffrey

“Here’s the problem,” says one former Disney staffer. “When Jeffrey is focused on a single thing, there’s no one better. Because Jeffrey’s so good, Michael has allowed him the freedom to look into other areas. He made Disney Television a personal mission; he got involved in a lot of areas of the company. Jeffrey flew off to the park in Japan and came back and said, “The toilet in stall No. 3 at the Space Mountain Ride isn’t working.’ Jeffrey got into too many things.”

On January 11, 1991, Jeffrey Katzenberg distributed a 28-page memo to fewer than a dozen top executives at the studio. Called “The World Is Changing: Some Thoughts on Our Business,” it was sent out on what was known around the studio as “weekend read.” To the great glee of everyone in Hollywood, it was soon going out on fax machines all over town, followed by an anonymously written 25-page parody. By the end of the month, it was reprinted in its entirely in Daily Variety. “Everyone at the studio felt the memo was an apology for the year to come,” one former Disney executive says. “He had already seen the disappointed returns from Rescuers and Three Men and a Little Lady, and I don’t think he felt he had a hit among the rest of the batch. They felt it was written by Jeffrey the politician, Jeffrey the survivor.”

Only a few insiders realized that the Katzenberg Memo, as it quickly came to be called, was in large part a restatement of the major points of Michael Eisner’s 1981 memo to Charles Bluhdorn. (“Michael jokes that he plagiarized it,” one insider says.) “Since 1984,” Katzenberg wrote, “we have slowly drifted away from our original vision f how to run our movie business.” Then he spent 28 pages repeating the principles form the Paramount Philosophy Paper — adding one new one: “People don’t want to see what they’ve already seen.”

“Having tried and succeeded, we should now look long and hard at the blockbuster business …,” he wrote, “and get out of it … The number of hours [Dick Tracy] required, the amount of anxiety it generated and the amount of dollars that needed to be expended were disproportionate to the amount of success achieved … Dick Tracy was a great experience … but as much as Dick Tracy was about successful filmmaking, it was also about losing control of our own destiny. And that’s too high a price to pay for any movie.”

On March 31st, Disney declared declining six-month earnings for the first time since Eisner took over. The company’s second-quarter net income declined 29 percent, to $126.6 million from $178.5 million the year before. The film-entertainment division’s operating profit (which accounted for about one-third of the company’s net income) fell 20 percent, to $46.2 million from $57.8 million the year before. At a time when the rest of the industry’s box office stayed strong, the company’s earnings were also hit badly by the recession and declining attendance at Disney’s theme parks and hotels, combined with the cost of expanding theme park and hotel and real-estate projects, including Euro Disney, outside Paris.

On June 30, Disney had to announce once against that its net profits for the quarter had fallen 31 percent from the same quarter the year before, to $165.5 million. The profits for the film division rose 8 percent from the previous year’s quarter, to $79.1 million from $73.3 million, due to the fact that the studio released four profitable videocassettes in the quarter, compared to one in the same quarter the year before. Eisner issued a statement saying the decline was the result of lower levels of domestic and international travel, the current recession, and less than expected box-office performance.

The financial outlook for the immediate future is not bright. “The film division is going to have another difficult year is profitability,” says Wall Street analyst Harold Vogel of Merrill Lynch. “The international release of this year’s films won’t be as strong, and the video sales will be slower. Last year, they had very high foreign sales with Pretty Woman and Little Mermaid, and they won’t have anything like that this coming year.” Says Manny Gerard much more bluntly, “It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out how this year’s pictures are going to do overseas. Except for Green Card, because it had Gérard Depardieu, and Three Men and a Little Lady, it’s going down the toilet.”

“Studios have different personalities,” producer Robert Cort says. “There are very hysterical, truly out-there studios and very paranoid studios. Disney is a very obsessive-compulsive studio. And you know obsessive-compulsives: When they have a problem, they will be very compulsive about how they deal with their problem. Disney right now is saying, ‘All right, let’s look at ourselves.’ I really respect those guys for doing that.”

Even before Jeffrey Katzenberg wrote his memo, he was looking for ways to try to bring in new types of films to Disney and ways to bring in big films with less risk. Several months before, he signed a deal with former Carolco partner Andy Vajna, who produced the big-budget action-adventure Rambo films. The five-year deal called for Disney to distribute the Vajna films. In the memo, Katzenberg wrote that this would allow Disney “considerable upside potential with minimal downside risk.”

At the same time, Katzenberg was negotiating a deal with independent producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, his old friends from Paramount, who produced Beverly Hills Cop, 48 HRS., and the big-budget Days of Thunder. In the memo, Katzenberg assured his staff that the deal “will be structured so they will be extremely well rewarded in success. But they will be at substantial risk, along with us, in failure.”

Even more dramatic that that was what began happening a couple of months after the memo was written. Katzenberg started talking about how he was going to give up some control. “I understand that Michael told him, ‘You’ve got to let these guys have more say; you’re running the whole studio,’” says one studio executive who has spoken to Hoberman and Mestres. “In February and March, Michael really tried to stop in and get him to allow the guys more autonomy. According to David and Ricardo, he was very forceful then.”

The question now is whether Hoberman and Menstres will be able to take this opportunity and run with it. Those who have worked with the two men say they are placing bets on Hoberman. “David has always given Jeffrey less of his way then Ricardo has,” one says. “I think Ricardo is more of a soldier and David is more of a partner.” Says another, “One of the theories about why Hollywood Pictures has failed is that Ricardo serves on a platter to Jeffrey all the movies that Jeffrey wouldn’t make.”

Katzenberg continued to insist that he did not have time to talk about these changes. And Hoberman and Mestres, despite that new autonomy they are supposed to be acquiring, said they could not talk if Katzenberg was not going to talk. But Michael Peyser, the senior vice-president for production at Hollywood Pictures, did agree to talk on the record about the changes at the studio.

“There’s an understanding that sometimes in companies, the company can be perceived as one person,” Payser said. “There’s a consciousness on Jeffrey’s part and everybody’s to say that’s never really been the case and it’s important to let filmmakers know we want to work with them and help create their movies. Remember when they used to build houses with diagonal supports in the walls, and then they stopped using them and realized houses are just as strong? I think that’s what we’re realizing. We don’t need to create such a support system, and in fact there may be more breathing room if we don’t.

“There was a strong feeling at this level of senior management that there was a frustration with the process. It was something that was recognized quite clearly by the rest of senior management, Katzenberg, Eisner. To some extent, Ricardo and David have been instrumental in bringing that to bear and making their companies their own companies.”

“So not every decision is made by Jeffrey now?” I asked.

“Those days are long gone,” he said.

Peyser said that the changes had nothing to do with “any one string of films, successes or failures.”

“Do you really believe that they would be talking about changes if the studio wasn’t having a rough year?” I asked.

He laughed. “It’s harder to get people to respond if you’re winning every day,” he said. “Obviously it’s responsive. But the internal impetus has always been there. One positive thing I should say. I think what’s going on is a testament to the smartness of these guys. What’s smart about them is that they’re not deaf.”

In July and August, Katzenberg took the same message out on the town. In an unusual series of meetings that had everyone buzzing, he visited all the powerful talent agents and lawyers in Hollywood. The meetings served two functions: He wanted to meet younger agents whom he had never met, and he wanted to talk about the new way Disney was going to do business. It was a way of trying to patch up his relations with a group of people among whom it had become to say, “The last place we’ll take this is to Disney.”

He told the agents and lawyers he planned to step back and let Hoberman and Mestres take more control. “He talked about giving more creative freedom to filmmakers if they made a film cheaply,” one of the lawyers says. “He said if it’s a very expensive film, he’s going to interfere. If it’s not, there will be less interference. He was also trying to say they will become a kinder, gentler nation in terms of negotiating. He said they will try to make deal-making a little smoother. He apologized for making a big mistake in green-lighting all of these expensive movies. He said there’s a new era; he’s going to make less expensive movies and give more creative freedom. I think everybody’s attitude is: We’ll wait and see.”

The Walt Disney Studios still have to get through at least one more year without a big hit in sight. The best possibilities the studio can cite as strong Thanksgiving/Christmas movies come from the new animated version of Beauty and the Beast and a remake of the Spencer Tracy–Elizabeth Taylor classic Father of the Bride, starring Steve Martin and Diane Keaton. The only films the studio can point to as possible big summer releases are Sister Act, a comedy starring Whoopi Goldberg as a nun, and Encino Man, a film starring MTV comic Pauly Shore.

In November, the studio is going to have to ride out the storm of publicity about Billy Bathgate, which has already been dubbed “Billygate” after the disastrous Heaven’s Gate. The film, based on the E.L. Doctorow novel, stars Dustin Hoffman and Bruce Willis and is being directed by Robert Benton. It was originally set to open in June, then was postponed while Dustin Hoffman finished shooting Hook (the Steven Spielberg version of Peter Pan, which is expected to be the big movie of this Christmas season) before coming back to New York for reshooting. The film’s budget has risen to $40 million amid rumors of unhappiness among the Disney executives.

Still, no one knows better than Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg that all it takes is one big film to turn their fortunes around. It’s popular now in Hollywood to say that it can’t be found on their release list. “Ask them what their summer movie is,” said the producer who says he is “too old and too rich” to work for them. “Ask them! They don’t have one!” But no one picked Pretty Woman ahead of time. No one picked Home Alone. No one picked Ghost. All it will take is another Pretty Woman to come out of nowhere and Eisner and Katzenberg will be heroes again.

“I’m convinced it’s a cyclical thing,” says Chris Zarpas, the man who owes his career to Disney. “I honestly believe the Movie God flies around town and settles down at a commissary for a couple of years and then flies on. That’s part of what keeps people going in this business — the magical and mysterious nature of it.”