This article originally ran on February 3, 2017. We’ve republished it now alongside the release of Episode 3 of Land of the Giants: The Disney Dilemma, a Vulture-Vox Media Podcast Network collaboration that looks at the many facets and ever-changing fortunes of the sprawling entertainment company. You can listen to it here, and follow the entire series at the Disney Dilemma hub.

In 1944, Disney rereleased Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs into theaters nationwide. The film had been a sensation during its original 1937 release — in addition to being a virtuoso technical achievement as the first feature-length animated film, it was also a critical darling and commercial smash. And while the move to rerelease the film was more of a marketing decision than a creative one (the studio had nearly been crippled, creatively and financially, by America’s involvement in World War II, and none of its subsequent features had captured the Zeitgeist like Snow White had), it set a precedent for the studio, which would soon standardize the practice of both releasing and then withholding its animated classics. The philosophy was to take each film out of circulation for about seven years, which studio honchos felt created a sense of urgency and excitement, and built additional mystique. When Michael Eisner and Frank Wells took over Disney in another tumultuous period for the company, the 1980s, they decided to release many of the most sought-after animated titles on VHS, a controversial move at the time. But the duo ended up following in the footsteps of those original theatrical exhibitions — the movies would appear on video for a limited time, then disappear from stores. Only this time they had a name for where the movies went when you could no longer get them: the Disney Vault.

For most, the Disney Vault seems like something intangible — a marketing gimmick and source for misplaced rage (there are a handful of YouTube videos railing against the Vault and all that it stands for). Disney, for its part, has done much to perpetuate the gauzy notion of the Disney Vault as something real but out of sight, existing, like so many Disney fantasy realms, in your imagination more so than in real life. But it does exist. And I’ve been inside.

In an anonymous block of Glendale, California, sits a nondescript beige building free of signage or distinction. The only thing that would even alert you to the fact that this is the Disney equivalent of Fort Knox is the abundance of insane security procedures stationed around the building. Even for employees of the company, the building remains elusive and hard to gain entry to. (Full disclosure: I worked for the company for almost two years and never once got to go.) Unlike the main studio archives down the street, which are housed in an inviting glass building with ample signage — it’s this location that appears on-camera whenever the company makes documentaries about the Disney Vault — this place feels like a mirage.

When you get inside the lobby, you’re alerted to the fact that this is the only place in the entire facility that you can take photos. A tall man named Tom says that if you do take photos, for the love of God do not geo-tag your location. For all intents and purposes, this building is off the grid. It’s Disney’s Area 51. Welcome to the Animation Research Library.

Looking around the lobby, you can already feel the history — on the ceiling are the lantern-like light fixtures that used to hang in the Walt Disney Animation Studio building in Burbank before the recent remodel; in the corner sits a piano that used to be in the Animation Studio’s so-called “music room”; against a wall is an animation desk used by Pres Romanillos, an animator who would etch his characters into the wood frame of the desk (Pres died in 2010 at the age of 47). The building itself is something of a lost Disney treasure. It’s the place where movies like The Little Mermaid and Aladdin were produced, after the animation unit had been kicked off of the Disney lot and before the “hat building” had been constructed down the street in Burbank. When the Northridge earthquake struck during the production of The Lion King, some animators lived in this building. And we haven’t even gotten into the actual vault yet.

Before we go in, Tom tells us, we have to relinquish all pens. He points toward a small container of pencils that we can borrow, but I just made notes on my iPhone. Tom says to watch swinging bags or backpacks because original art will be on display. Again: No fucking photos.

Just in terms of size, the vault is insane — there are 12 vaults, each organized by project. This includes everything from the original sketches for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to larger-scale items like all of the puppets from The Nightmare Before Christmas and Frankenweenie. Each room is climate controlled and meticulously catalogued, with state-of-the-art security and fire-suppression systems in place. By the library’s own estimates, there are something like 65 million pieces of art in the collection, which makes it the largest collection of animation artwork in the entire world. The vaults look like what you’d think something like this might — the rows of stuff are located in cabinets which can be moved with a big spinning handle (like a vault), so you can easily get to them. As for the artwork, it’s filed in a way that it should be, with cells or production artwork stacked horizontally, while other, less sensitive items are filed vertically, in accordion-style folders. Oversize items like large background paintings are housed in separate flat files. The sensation of walking into one of the vaults is like stumbling into the warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, except instead of sensitive government and historical secrets, there are a bunch of sketches of Mulan, and also some guy named Tom yelling at you to stay behind the yellow line.

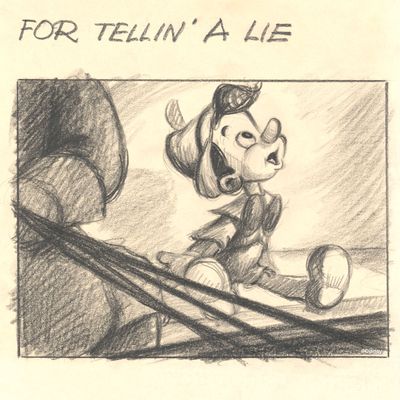

I was there as part of a small group of journalists who had been brought to the building ostensibly to celebrate Pinocchio leaving the Disney Vault with a digital rerelease. While there, I got to chat with Fox Carney, the manager at the Animation Research Library, and he told me that the archives contained “over a million” pieces of artwork for Pinocchio alone.

Of course, the library is not exhaustive; there are gaps, like an untold amount of artwork that Walt Disney personally gifted to Ray Bradbury. When I asked Carney if there was something that he really wished he had in the collection, he mentioned Pinocchio. The making of the film was notoriously “torturous” (Carney’s words), with whole sequences that were fully animated and then abandoned.

“A lot of that art may not exist,” Carney admitted. We were standing by a large area toward the back of the building called the Black Table, which is, true to form, a huge black table where pieces are examined, either for the prying eyes of visiting journalists or for official use, before being categorized, sorted, and catalogued. They may not have held onto that artwork. But if we were to make a fictional, Indiana Jones–style story, there would be a storage unit somewhere in North Hollywood that’s been rented out since 1938 that has all of this artwork in it. But that’s bordering on the realm of fantasy.

Besides storage, the main purpose of the Vault is curatorial. This is where art is assembled and distributed for things like traveling exhibitions, whether it’s a gallery of Disney artwork that recently opened in mainland China, or a walkthrough for D23 Expo, the biannual all-Disney version of Comic Con. The other function is educational. Carney says that most of his day is spent fielding requests from other parts of the larger Disney empire — Consumer Products, Imagineering — asking to take a look at items from the library for their own projects, whether it be a new theme-park attraction or piece of film-specific merchandise. For this Pinocchio rerelease, Carney told me a team of five archivists worked for almost a year compiling material.

The vault can also be helpful for those writing about these animated masterworks. I spoke to J.B. Kaufman, whose book Pinocchio: The Making of the Disney Epic, is the definitive account of the film’s production. “A lot of what I look at is the exposure sheets,” Kaufman told me. “The exposure sheets will tell you a lot of information that just isn’t available anywhere else. And when they did retake orders [an instruction to reanimate a given sequence], those are filed with the exposure sheets. I was researching the sequence where the Blue Fairy comes to Geppetto’s workshop, and there’s a scene that serves as a Rosetta stone, where they were establishing how this character was animated. There were 11 retake orders for this one scene.” Kaufman added: “That, to me, was one of the great eye-openers — to see just how meticulous they were about getting that aspect exactly right.”

That’s the thrill of going into the Disney Vault — you can literally stumble upon something that no one has seen in decades. “Any given day, you can open a box and see art that people maybe haven’t looked at in 20, 30, 40 years,” Carney told me.

Like most libraries, the Animation Research Library is creeping into the digital age. At one point during the tour, we stepped into a room where a small team of technicians was working on digitizing the massive amount of content. They say that the task is turning “physical into digital,” and that the payoff is incalculable. These are beyond high-resolution files, which can take up to two minutes to capture and download. Everything is captured, from cigarette burns and coffee stains, to off-the-cuff notes from the animators. For things like artwork from Sleeping Beauty, which was shot on 70mm and required animators to work on pieces of paper the size of bed sheets, they use a special process where a vacuum system sucks the artwork onto a table and then moves, like on a conveyor belt, so that it can be captured fully. Once the artwork is digitized, it’s moved onto a system called GEMS, which is accessible by employees of Walt Disney Animation Studio, Pixar, and Disney Toon Studio (makers of the Planes films). After the artwork is digitized, you can watch entire sequences play out in their rough form, and zoom in to see the detail background painters put into Geppetto’s workshop with alarming clarity.

The process is daunting. So far a little more than one million images have been captured, and there’s still a long way to go. But on the back end, the benefits will be huge. “This company is really investing a lot in this,” Carney said. “It’s beyond the bottom line. It’s bigger than anything.”

And that’s the biggest takeaway from visiting the Disney Vault — it’s a place where you can relive the past (sometimes literally, given that you can move through the years as you travel through the vaults), but one that will also inform the future, both in the way these pieces are discovered and discussed, and in the way they’ll inspire future artists and animators for decades to come. Good luck getting inside, though.