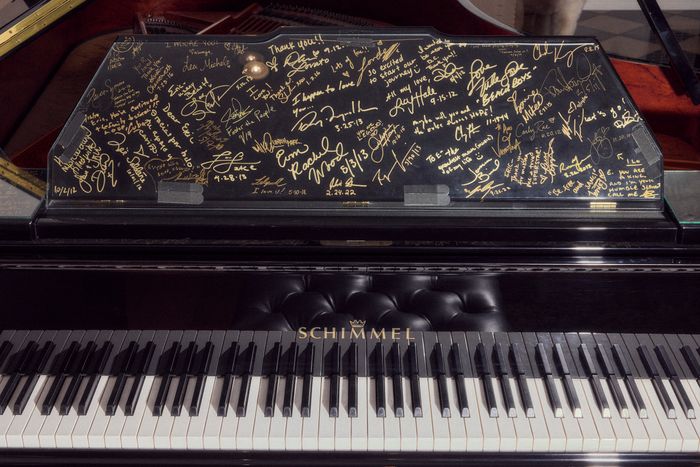

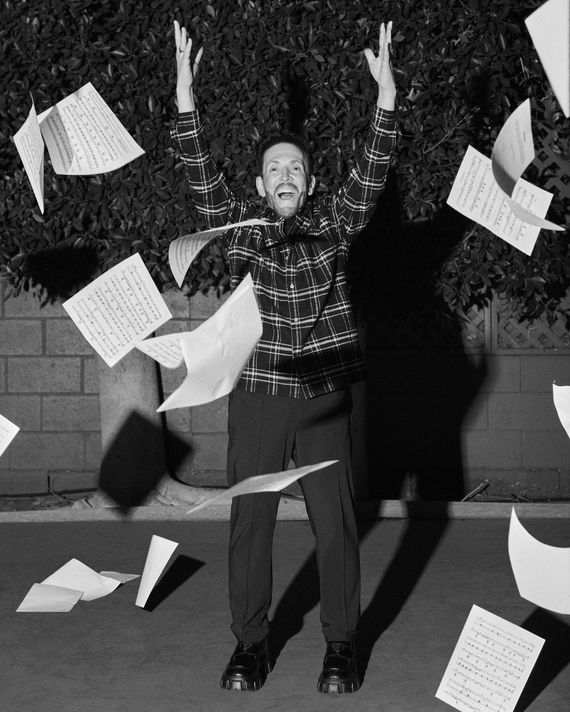

Eric Vetro’s home is entirely ordinary for a nice neighborhood in the Valley, except for the fact that it looks exactly like a house from the opening credits of a sitcom; walking in the door, you half-expect to bonk your head on an executive-producer credit. Once inside, you’ll find the ground floor is an unofficial yearbook for Hollywood’s A-list. In the living room sits a piano covered in hundreds of signatures (THANK YOU FOR YOUR PURE IMAGINATION! —timothée chalamet). An entire wall of his office is plastered with selfies, over 70 in all, showing Vetro grinning alongside his celebrity students. The other three display gold and platinum records, many featuring personalized messages. PRESENTED TO ERIC VETRO IN RECOGNITION OF ACTUALLY TEACHING PALOMA FAITH HOW TO SING, reads one. CAUSE LET’S FACE IT SHE WAS SHIT BEFORE. AND NOW SHE’S SOLD ABOUT 4 MILLION ALBUMS!

Vetro is a vocal coach to the stars, and for years his home on a quiet street in Toluca Lake, Los Angeles, has been a pilgrimage site for anyone who wants to make a living in the entertainment industry. Students appreciate the privacy: There’s a U-shaped driveway and a fence to provide protection from the paparazzi, though they sometimes get through. (He swears they caught him changing once.)

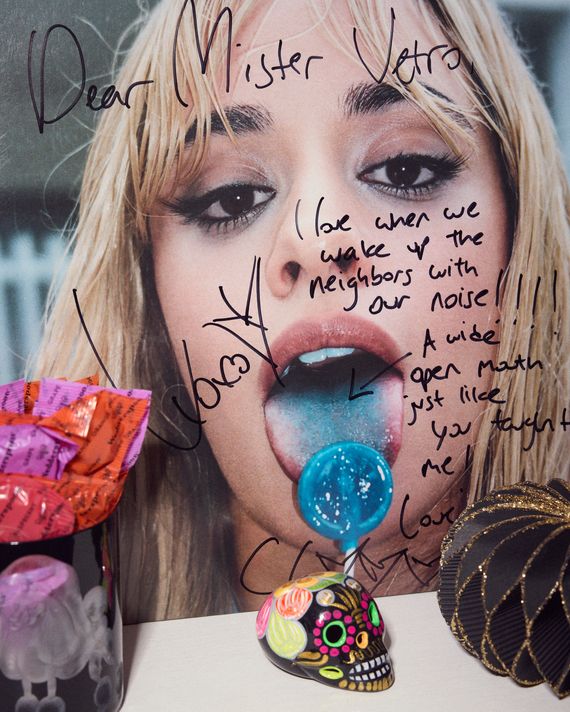

Vetro’s primary job is working with professional singers of every age and every genre, from Bette Midler to Omar Apollo. But if you’ve heard of the bright-eyed 68-year-old, it’s likely because of his sideline. Some time ago, Hollywood determined that it was easier to teach actors how to sing than teach singers how to act, and Vetro is the guy hired to get them there. He taught Emma Stone for La La Land and Renée Zellweger for Judy. He taught Austin Butler and Jacob Elordi how to croon like Elvis and Jeremy Allen White to sound like Springsteen. It is a good time to be a student of Vetro’s. Sabrina Carpenter, whom he has coached since she was a preteen, has been nominated for a half-dozen Grammys, and five actors who studied under him are in the hunt for Oscar nominations. On Maria, Vetro helped Angelina Jolie learn to sing opera. For A Complete Unknown, he aided Chalamet’s transformation into Bob Dylan and taught Monica Barbaro to nail Joan Baez’s vibrato. On Wicked, he worked with Jonathan Bailey as well as perhaps his most famous client, Ariana Grande, whom he has tutored for over 15 years. He is rooting for them but would never want to take credit for their success. And, of course, Vetro notes, he has worked with much of the competition as well.

“Eric is an institution,” says Will Ferrell, who has worked with him on three films. “He doesn’t necessarily get enough recognition for all that he does for musicians,” says Barbaro. “They don’t really have a vocal-coach award, but if there was one, he’d be Meryl Streep.”

Vetro credits this omnipresence to his emotional intelligence. “I can read the room really well,” he says, quickly assessing whether students need kindness and sensitivity or tough love and a firm push. But you can also point to the extraordinary lengths to which Vetro goes for his clients. He usually works with eight or nine a day, some in person, some FaceTiming in from all over the world. “We’ve done warm-ups everywhere: the bath, the shower, on the toilet,” says Camila Cabello. “I’ve been the woman making crazy sounds on the phone walking through the streets of Saint-Tropez.”

Vetro teaches every weekend. Besides a four-day stint at Deepak Chopra’s meditation retreat about a decade ago, he has not taken a vacation since 2008, when he accompanied a student’s family on an African safari. (“The closest he was going to get to a bush,” his friend the songwriter Diane Warren jokes.) Upstairs in his bedroom, he sleeps in a hospital-style bed with a fold-up back, just in case he needs to wake up in the middle of the night to lead a vocal lesson. In this event, he simply works from bed with his iPad and a keyboard ready on a tray table. Vetro prides himself on being able to fall asleep with nothing but a mantra: Let’s relax, go to sleep, and heal our body from the day.

“What you put into your head at night really affects your body,” Vetro says. “All of my dogs have lived to a very old age. I would have them go to sleep with me, saying, ‘You’re such a good dog.’ If you plant those good thoughts, it really helps boost the immune system.”

Increasingly, today’s singers need someone like Vetro. “A lot of artists are becoming famous without having developed as a live vocalist,” says John Legend, who connected with Vetro through his Voice co-panelist Grande, with whom he also shares a lawyer. Legend notes that these YouTube or TikTok stars now “have to actually figure out how to sing live. The clock is ticking.”

But it’s also the music itself that has changed. While there have always been autobiographical songs, 21st-century pop is more diaristic. “Bette Midler or Barbra Streisand, if they sang a sad song, it didn’t necessarily have anything to do with their life,” Vetro says. “Whereas the kids today, they take it very personally that a song represents where they were at that moment. If they’re writing about a breakup, months from now they’re not feeling that way anymore. They’re like, ‘I don’t want to sing that song.’ It’s not even a year old.”

When Vetro first started teaching, he focused almost exclusively on technique. “Giving people all the rules, how to practice,” he says. “I realized along the way there’s much more to it than that.” A singer’s mood, their mind-set, whom they’ve got around them — all of it contributes to the way they sound: “Some people have a little bit of drama in their family. I say, ‘Ask your family, if they have something important to talk to you about, if they can’t do it within a certain amount of hours of the show. Preferably the next day. Because that’s going to be in your head.’” Proper feedback is essential, Vetro explains. “If you go, ‘Are you smoking cigarettes?,’ that is not inspirational. Now they don’t feel good about themselves. But if you go, ‘I think that could even be better. What have you been doing lately?’ They always admit what they’re doing. Then I go, ‘Try not to, and let’s see if it affects you in a good way.’” He laughs. “I know it will.”

From talking to a few of his students, I got the sense that Vetro is almost as much a therapist as he is a vocal coach, because they said things like “He’s like my therapist.” “I’m an anxious wreck sometimes, and Eric has gotten me through some of the most difficult moments of my life,” says Shawn Mendes. “Eric is there for me constantly to ease my nerves and anxiety,” says Lea Michele via email. “I can be feeling unmotivated or insecure, and he can talk me out of it,” says Cabello. It’s mostly the younger artists who feel this way, though. “I definitely need less of that,” says John Legend. “I’m pretty in control of that myself.”

Slightly bend your knees, and hang forward like a rag doll. Your head and arms are loose and free. Take a deep, silent breath in, then exhale. Take another deep, silent breath in. Now hiss as you slowly roll up into a standing position, letting all tightness and tension out of your body. You are now ready to sing with Eric Vetro.

I wanted to see how Vetro might handle a person who was totally unqualified to star in a music biopic, so I hooked him up with the worst singer I know: myself. When I told Vetro my singing was considered painful to listen to, he shared a story about Stephanie Beatriz: She had been told when she was young that she was a bad singer, but then she went out for In the Heights, and look what happened. Vetro is not one of those hippies who believe anyone can sing. Nevertheless, he advised me to “let go of any of the past thinking you had, especially from childhood.”

Over Zoom, Vetro first led me through a series of basic vocal exercises, during which I resembled a donkey mourning the death of its beloved mother. “The more you practice those, the smoother they will get,” he said. The plan was to take only a single lesson. But at the end of the session, Vetro couldn’t help himself from giving me homework, so of course we had to go again. One thing led to another, and Vetro wound up giving me a dozen vocal lessons over the course of nearly a year and a half. I was well aware that these lessons were his livelihood and on multiple occasions attempted to release him from his obligation. Every time, he turned me down.

“This is fun for me,” he said the first time. “Everyone I work with, it’s very pressurized. They’ve got to sound good, whether it’s on tour or for an awards show. I hear artists say all the time, ‘I’d like to get back to the way it was when I was 15 years old, when I was just enjoying it.’” Later, he would express similar sentiments: “It doesn’t matter where someone is in their career; everything’s important. There’s never a time you go, We can coast. That’s why working with you has been such a pleasure. Your life isn’t depending on this.”

Mendes describes Vetro as rooted: “Nothing fazes him.” However, despite his unyieldingly positive demeanor, any number of factors can stress him out. My first visit to Vetro’s house took place the day after the 2024 Oscars, at which his student Becky G had sung Warren’s nominated song from the movie Flamin’ Hot. “Certain things are out of my control, but they still frustrate me,” he says. “Hypothetically, if someone sings at an awards show and I think the sound wasn’t mixed well, there’s nothing I can do about it.” (He emphasized this was indeed a hypothetical.) He has seen a stylist accidentally put hair spray onto a singer’s lavalier mic and muffle their vocals. Even worse, spray it into the singer’s mouth and give them a catch in their throat. This is Vetro’s worst nightmare: that the audience won’t be able to hear all the hard work a student has been putting in to get their voice as strong as possible.

Then there are the nights when everything goes right. Vetro likes to recall the time in 2016 when Grande served as the host and musical guest of Saturday Night Live, a gig that came with long hours, unpredictable conditions, and a high degree of difficulty. “She got out there and started singing. I saw this look on her face, the way her body started to sway a little bit. She was relaxed and enjoying herself, and it was going perfectly,” he says. “I can’t even tell you what that felt like. It was like, Oh my God, she’s in heaven. I could not sleep that night because I was so buzzed. When you’re a part of something like that, it’s exhilarating.”

For as long as Vetro can remember, he has loved listening to people sing. Except for a three-month stint as a PR intern in 1988, he has never had a job other than working with vocalists. “For some reason, my brain goes right to the voice,” he says. “There can be the best pianist, guitarist — whatever. I don’t hear the instrument; I just hear the voice. It’s a strange thing, but that’s how it’s always been.” As a child, he entertained himself by giving imaginary voice lessons in his head. The first real lesson he taught was in the fifth grade. “The most popular kid in our class wanted to audition for a musical skit,” Vetro says. “I taught him a song that he could sing. We didn’t hang out and stay friendly. He was into sports; I was, obviously, into music. But there was something between us from that point on.” He found it an eye-opening experience: “I had a gift that I could give to someone, and it would bond me to them.”

Vetro grew up in upstate New York, the son of “a lawyer who never enjoyed being a lawyer.” (In his kitchen, he has hung a set of landscapes by his father: “One of the only times he was in a good mood was when he was painting.”) He went to NYU for college and began tutoring classmates on the side. He was unpaid until one girl’s grandmother began making him dinner. “Then someone came up to me and said, ‘I can’t feed you, but I’ll pay you.’” Vetro had not even considered the fact that he was being paid in food: “I was doing it for fun. But that triggered an avalanche of people.”

He played piano in other people’s lessons, too. Vetro reckons that, by the time he was 25, he had observed more than 20 different vocal teachers. That turned into a gig accompanying cabaret singers. His rise as a vocal coach was so incremental that he has a hard time remembering when he felt like he’d made it. “Somebody being in the chorus of a Broadway show was a big thing. Then it was the understudy of the Broadway show. Then the star. Then all of a sudden, I was working every day,” Vetro says. “But it was gradual. If it had happened overnight, I wouldn’t have been able to handle it very well.”

Vetro moved to L.A. after graduation. “My parents thought the whole idea was absolutely insane,” he says. “My father was very negative about it: ‘What makes you think anybody’s going to want to work with you?’ I just had this core belief inside that it would happen. My idea in life was always, If you put out a great product, they’re going to want to buy it.”

Vetro is not one of those teachers who swear by a certain philosophy or method. “If someone says, ‘I teach the [Blank] Technique’ or whatever, I get suspicious,” he says. He tries to work holistically, tailoring his lessons to each individual student. With Cabello, their current focus is strengthening her voice in the upper register by playing around with songs by Beyoncé, Whitney Houston, and Céline Dion. “My music is not very belt-y,” Cabello says. “My style of writing is more Swedish-pop melodies. So it’s good for my voice to stretch to power ballads.”

If there is one through-line in Vetro’s pedagogy, it’s a belief in the power of visualization. He often instructs his students to imagine themselves walking out onstage wearing something they want to wear and singing a song they love to sing. He wants them to visualize the whole song or even the whole show. “I have people say, ‘I became my own director — I realized I need to be a little more still,’” he says. He firmly believes that visualizing a successful performance can itself make his students better singers. “When people are able to free themselves and imagine themselves sounding really good, they start hearing it in their voice when they start singing,” he says. “It’s a mind-over-matter thing.”

Years ago, he was talking to an actress who was so stressed about singing live at a benefit concert that she’d given herself a psychosomatic fever. “She was burning up. I said to her, ‘If you know that you did it to yourself, isn’t the good news that you can get rid of the fever?’” A similar thing happened to Vetro in 2022. He was feeling “hugely overworked,” he says, when all of a sudden he had a terrible back problem. “After two months of it, I started to realize why: I was overwhelmed, and my body wanted me to shut down.”

When I spoke to Warren about her friendship with Vetro, she said they had one fundamental thing in common: “We’re both workaholics.” Vetro doesn’t love that word. “A workaholic is addicted to working hard,” he says. “I’m not. I’m addicted to being around people and helping them improve.” He tries not to call anyone out if they’re not putting in as many hours as he is, with one exception. “If one of my students, especially someone very young and on the cusp — I get a little nervous when they want to take too much time off,” he says. “Because in this business, there’s always someone ready to take your spot. You can’t just go, I’ve had all this success. I’m going to take six months off. Six months can make a big difference.”

I was still taking lessons with Vetro over the 2023 holiday season, which I spent with my in-laws. That Christmas morning, one member of the extended family skipped the festivities to give a tennis lesson. If he didn’t, he said, they’d hire someone else who would. This made me think of Vetro, and a week later, I told him so. “That kid is really smart,” Vetro said. He was reminded of someone who used to cut his hair years ago: “I asked, ‘Can I come at 9:30?’ And he said, ‘I’m sorry. I don’t start before ten.’ Not only did he lose me, but he lost anybody that I would’ve ever recommended him to. If he said, ‘I can’t because it throws me off,’ it would have been fine. But the way he said it was so diva — that blanket statement. If someone says to me, ‘I need the lesson at 6 a.m.,’ I say, ‘Okay.’”

Vetro used to throw extravagant Christmas parties. He’d put up a huge tent in his backyard with a grand piano in it. His cousin and her family would come in a week ahead of time to help him prepare. Another friend decorated the entire space with red roses. To keep them alive, Vetro would turn the heat off for two days, and freeze everyone in the house. The last time, Grande’s mother, Joan, co-hosted, and Grande herself performed. But it just got too big. Through his job, Vetro got to know not just his students, but also their entire entourage. Hollywood stars are surrounded by an entire constellation of professionals, who are often as close as family — managers, agents — plus actual family, of course. Vetro didn’t want to leave any of them out, so an invite for one singer could entail making space for up to 20 guests. At his final party, over 400 people came. “It was exhausting,” Vetro says. “Some agent called and I said, ‘I’m sorry you couldn’t make it to my Christmas party.’ He went, ‘I was at your Christmas.’ That’s when I started to think, This is ridiculous.”

Vetro now spends Thanksgiving and Christmas with a small group of friends that includes an actress, a singer, a former Navy SEAL who is now a real-estate broker, and Diane Warren. Vetro had been a fan of hers since the ‘80s, and they finally got close in the Aughts, around the time they both worked on Meat Loaf’s album Bat Out of Hell III. They became fast friends, and claim that, to this day, they’ve never had a serious fight. In October, Vetro and I met Warren in her studio.“Our group of friends, most of them are high-level achievers,” Vetro said. “No one says, ‘I want to quit, I want to retire.’”

“That’d be like retiring from breathing,” Warren said.

“The only thing that scares me the tiniest bit,” Vetro said, “is that I feel sad for whoever …” He mimed playing the keyboards, then suddenly dropping dead. “That’s the only time I’m going to stop. And I feel bad for the last student, who has to have a teacher who died.”

Vetro and Warren are both paid to provide a service for artists, but they conceive of their relationships in a different way. “Do you feel like everybody appreciates you?” Warren asked him. “In my life some people do, and some people don’t.” She didn’t want to sound bitter, she said, reiterating that she never took a collaboration for granted. But she’d written songs that had made singers’ careers. “Most people are pretty grateful. Some people, they kind of forget.”

I once asked Vetro something similar: Do people say thank you? “Everything I’m wearing is a thank-you,” he said. He pointed to his Rolex watch, his Gucci bracelet, his Prada shoes. “People thank me all the time. And even if they don’t, I can feel it in their energy.”

“What Diane does not seem to understand is that I really form long-lasting relationships with these people,” Vetro added later. “They deal with her like buying a product. If you buy a painting from an artist, you might not want to spend time with them, you know? She always says, ‘They’re not your friends.’ And I’m like, they actually are.”

By the end of our months together, I understood what he meant. As with Shawn Mendes, Vetro had helped me through difficult moments of my life, too. (Our lessons overlapped with the lead-up to my wedding, which prompted at least one meltdown worthy of a pop diva.) And he had worked tirelessly to turn me into a better singer. He had me blow bubbles through a straw to work on my breath, and sing while shaking my fists in order to stay loose. I held my hands in the air and dropped them on the high note like I was Lydia Tár. Physically, my form was improving. But I still wasn’t singing in tune. I liked to jump out and attack the notes, to show them I wasn’t scared. Vetro’s solution turned out to be elegantly simple. “I want you to do something different this time,” he told me midway through our eighth lesson “Take a second. Listen in your head how you want it to sound. Then sing.”

The results, I’m sad to say, were immediate. Vetro was pleased I had finally seen firsthand the power of visualization. “There will be other areas in your life you’re going to be able to apply it.” He encouraged me to keep practicing. “People will say, ‘I wasn’t in the greatest mood, but I vocalized and my whole day was better.’ Every day we are confronted with negative things, but it’s how we react to it, how we choose to be beacons of light to other people. Isn’t it fun when you’re able to find that key?”