This post has been updated to include the appearance of James Baldwin in episode five.

Seven years after Ryan Murphy gave us the ultimate onscreen–off-screen catfight with Bette and Joan, the Feud anthology has finally returned with a vengeance, this time in the form of Capote vs. the Swans. Instead of 1960s Hollywood, the setting has moved to high-society New York of the 1970s, where Truman Capote, the celebrated author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood, is firmly ensconced in this world of ladies who lunch. That is, until he publishes a scathing excerpt titled “La Côte Basque 1965,” from his forthcoming book, Answered Prayers, in the November 1975 issue of Esquire magazine. Capote doesn’t just dish on his darling lady friends, whom he dubbed “the Swans”; he spills his entire teacup.

Suddenly, Capote finds himself iced out by his beloved coterie, which forms the main conflict of Feud: Capote vs. the Swans. The FX limited series is based on Laurence Leamer’s 2021 book, Capote’s Women: A True Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era, though executive producer Murphy, lead writer Jon Robin Baitz, and their team do rely on other sources to bring the drama.

Capote vs. the Swans’s tagline — “The Original Housewives” — deftly hooks its 2024 audience with its promised catty moments (of which there are plenty). But if you’re sitting there frantically Googling these glamorous 20th-century society doyennes and others who appear in Capote’s orbit, rest assured you’re not alone. Read on to find out how faithful FX’s production is to its real-life characters.

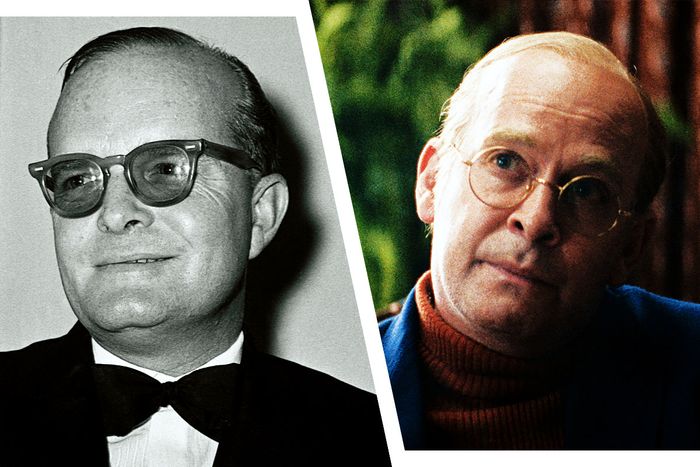

Truman Capote (Played by Tom Hollander)

While it’s impossible for anyone to eclipse Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Oscar-winning performance in 2005’s Capote, Hollander nimbly disappears into the role of Truman Capote by adopting the writer’s distinctive southern cadence and effete mannerisms. The most recognizable name in Feud’s cast of characters, Capote was at the height of his fame when he published “La Côte Basque 1965.” (The excerpt was named for the upscale New York restaurant famous for its French cuisine where Capote’s equally upscale lady friends would often dine. La Côte Basque shut its doors in 2004.) Nine years earlier, he’d solidified his placement in American literary history with the release of In Cold Blood, a groundbreaking work of narrative nonfiction investigating the 1959 murder of a Kansas farming family, as well as the capture and execution of the killers, that made Capote a bona fide celebrity.

Capote, as portrayed in Feud, was also during this time the close confidant of several well-to-do New York housewives. By revealing their deepest, darkest secrets in the Esquire article, the acclaimed writer committed social suicide. While he had been talking up Answered Prayers since 1958, Capote notoriously missed the book’s numerous deadlines, despite accepting hefty advances. Answered Prayers: The Unfinished Novel, was published in 1987, three years after Capote’s death in 1984. But it only consisted of a handful of chapters previously published in Esquire. Capote’s self-proclaimed “magnum opus” would never see the light of day.

Many of these details are presented true to form in Feud: Hollander’s Truman is seen regularly disregarding Answered Prayers’s deadlines, and his alcohol-and-drug-fueled path to self-destruction is a key element of Feud’s narrative. Would Capote have given up his vices, written another masterpiece, and lived beyond age 59 had he not published “La Côte Basque 1965” and alienated most of his Swan pals? That’s one of the questions Feud attempts to answer.

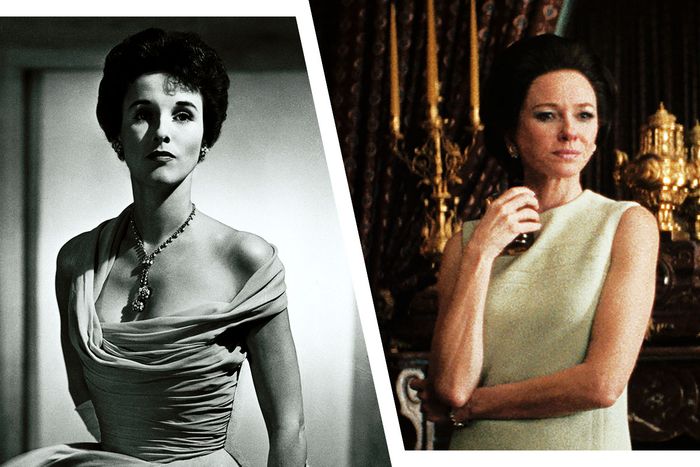

Barbara “Babe” Paley (Played by Naomi Watts)

Watts — also credited as a Feud executive producer — embodies the queen-bee role of Barbara “Babe” Paley. Capote famously described Babe as having “only one fault. She was perfect.” In Feud, Watts’s Babe is the quintessential socialite: She’s married to the Logan Roy of her day, William S. Paley, and could teach a master class in keeping up appearances. For example, she dutifully turns a blind eye to her husband’s numerous affairs and keeps her cancer diagnosis close to the vest — all while remaining impeccably dressed.

The first episode of Feud depicts Capote and Babe’s 1955 meet-cute as an initial case of mistaken identity: Hollywood producer David O. Selznick invites “Truman” to be his guest at the Paleys’ home in Jamaica — with the Paleys assuming Selznick meant former president “Harry S.,” not “Capote.” This was likely more of a re-creation of the story told in the series’ main source, Capote’s Women, and other accounts, than straight-up fact.

As Capote’s Women and Feud tell it, the greatest Housewives-ian betrayal occurs when Truman, Babe’s gay BFF, places Mr. and Mrs. Paley at the center of “La Côte Basque 1965.” The excerpt includes a salacious tale where “Sidney Dillon,” a media mogul married to the glamorous “Cleo Dillon,” has a one-night stand with the wife of New York’s governor — who leaves a (literal) permanent stain on the proceedings in the form of menstrual blood. From the moment “La Côte Basque 1965” hit stands, there was little doubt that “Sidney and Cleo Dillon” were thinly veiled versions of Bill and Babe Paley. The identity of the governor’s wife, however, is still a source of speculation: Feud portrays her as a vengeful Mary “Happy” Rockefeller, whereas Capote’s Women suggests the New York First Lady in question was Marie Harriman.

While Feud later includes a moment of brief, bittersweet interaction between Babe and Truman following the Esquire article’s publication, this was likely creative license. All reports say Babe Paley never spoke to Capote again. She died of lung cancer in 1978.

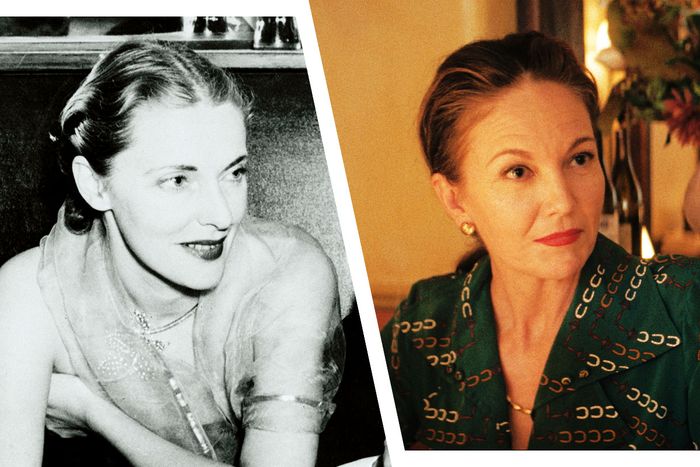

Nancy “Slim” Keith (Played by Diane Lane)

As the thrice-divorced Slim Keith, Lane serves as Feud’s central antagonist: Her character takes the lead in banishing Truman from the Swans’s social circles after “La Côte Basque 1965” is published. In another of Feud’s most Housewives-ian moves, Slim convinces Truman’s sole ally, C. Z. Guest, to disinvite the author from the Swans’s traditional Palm Beach Thanksgiving festivities in the second episode. She does so by guilting C. Z. with an extraordinary gift: A Verdura bracelet belonging to the cancer-stricken Babe Paley.

Whether or not Slim actually exerted that much energy in destroying Capote’s reputation remains a subject of debate; like Babe, the official line is that Slim Keith simply “never spoke” to the author after the Esquire article dropped. The series does suggest, however, that perhaps most of the Swans wouldn’t have ostracized Truman if it hadn’t been for Slim’s machinations.

Slim would’ve had every right to be livid at Capote, though. The writer unabashedly skewered the Salinas, California–born socialite in “La Côte Basque 1965,” painting her as “Lady Ina Coolbirth,” who delights in dishing about everyone from the British royal family to her dearest friends. In the first episode of Feud, Slim’s blunt remarks about Princess Margaret, a then-Prince Charles, and the rest of the royals are pulled almost word-for-word from “La Côte Basque 1965.”

What is true about Slim Keith is her evolution from modest upbringing to mid-20th-century “It” girl. Even more impressive is how she achieved this without becoming a Hollywood starlet. She romanced Clark Gable, befriended Ernest Hemingway, and boasted an impressive husband collection before dying in 1990: Her first two spouses were major Hollywood power players — producers Howard Hawks (hubby No. 1) and Leland Hayward (hubby No. 2). Slim’s third and final husband, Lord Kenneth Keith, whom she married in 1962 and divorced ten years later, provided Slim with her British title: Nancy, Lady Keith.

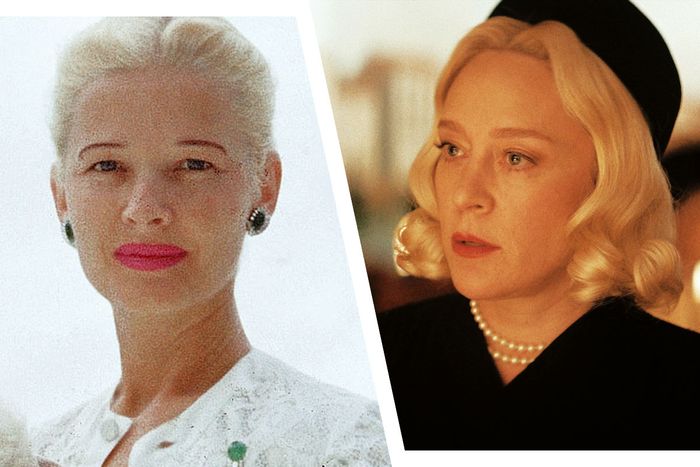

Lucy Douglas “C. Z.” Guest (Played by Chloë Sevigny)

One of the few socialites not featured in “La Côte Basque 1965,” Sevigny’s

C. Z. Guest has little reason to shun Truman. This makes her the only Swan still willing to be seen in public with the writer — though she is perfectly willing to scold him for airing his friends’ dirty laundry. Since C. Z. never fully excluded Truman from her life, Feud was able to re-create the middle-aged friends’ very real outing to Studio 54 in 1978 in an upcoming episode. Feud uses this incident to further illustrate the end of the era when C. Z. and her fellow Swans reigned supreme as glamour paragons. Instead of having fun at New York’s disco shrine, 58-year-old C. Z. feels exhausted, embarrassed, and out of place.

A true Boston Brahmin, C. Z. Guest lived a charmed life. (Also true? Feud’s portrayal of C. Z. as a devout gardener.) Born “Lucy,” her childhood nickname “Sissy” (for sister) eventually evolved into the distinctive “C. Z.” Like the other Swans, C. Z. was a mid-century style icon and socialite, her ice-blonde hair and simple fashion choices placing her on numerous best-dressed lists. (Capote referred to her as a “cool vanilla lady.”) She also took a husband well suited to her upbringing: Winston Frederick Churchill Guest, a polo player, steel-fortune heir, and second cousin of Winston Churchill.

Although C. Z. followed most of the rules of her world, she took a page from Slim Keith’s book during her younger days, dating film actors Errol Flynn and Victor Mature. But probably the juiciest story from C. Z.’s youth is the one where she posed nude for Mexican artist Diego Rivera in the 1940s — confirmed in multiple obituaries following her death in 2003 and referenced in the final episode of Feud. The painting in question can be found here, toward the bottom of the article.

Lee Radziwill (Played by Calista Flockhart)

Flockhart’s Lee Radziwill doesn’t get much screen time in the debut episodes of Feud; she’s absent from the first one altogether. But it doesn’t take long for Flockhart to put a beautifully bitchy spin on Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s dilettante sister.

Even though Lee Radziwill does appear in “La Côte Basque 1965” — Capote used her real name — she emerged unscathed compared to her friends Babe Paley and Slim Keith. So while Feud’s Lee doesn’t completely cut Truman out of her life, she does shift more into the frenemy zone. Their friendship ended for real around 1977, as portrayed in a later episode of Feud, when Radziwill wouldn’t testify as Capote’s source in a libel suit brought by writer Gore Vidal. (Vidal won.)

Born into the same world of privilege as her older sister, Caroline Lee Bouvier constantly found herself in Jackie’s shadow. So much so that, according to Capote’s Women, while Lee was having her own affair with Aristotle Onassis, the Greek shipping magnate’s interest quickly shifted from Lee to Jackie. Lee would spend most of her life trying anything and everything to stand out from the internationally beloved First Lady, including a disastrous acting attempt in a 1968 TV movie — written by her pal Truman Capote! Lee also played at marriage, garnering herself a “princess” title when she tied the knot with second husband Stanislaw Radziwill, a Polish prince.

Throughout Feud, Truman regularly comments on Lee’s inability to follow through on her attempted careers, but apparently Lee did have a talent for interior design. The most glaring creative license the series takes with Lee turns out to be regarding her death, killing her off three years prematurely.

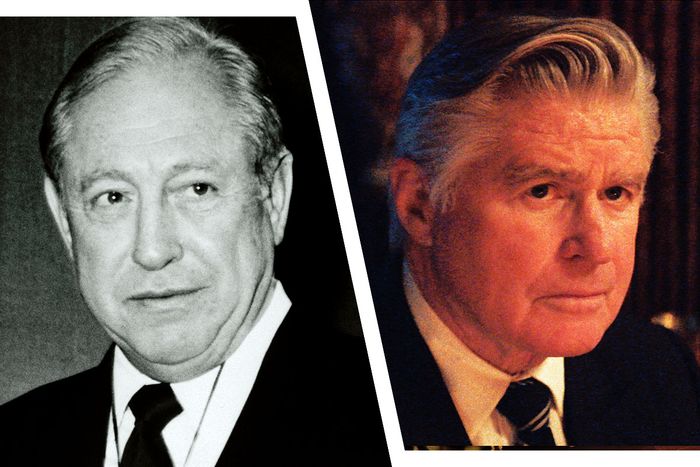

William S. “Bill” Paley (Played by Treat Williams)

Williams’s final onscreen role (the actor died in a motorcycle crash at age 71 in 2023), focuses more on the media mogul’s philandering — and there was a lot of philandering. But outside his penchant for cheating on his wife, Babe, Bill Paley — as in the Paley Center for Media — was a larger-than-life figure who revolutionized radio and television in the 20th century. He is credited with transforming several radio stations that composed the Columbia Broadcasting System (a.k.a. CBS) in the late 1920s into a communications empire. Under Paley’s leadership, CBS flourished as a news source anchored by journalism giants Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite. The network also prospered with runaway television successes like I Love Lucy, All in the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and M*A*S*H.

Although Feud goes deep into Bill Paley’s most notorious affair — the one that takes center stage in “La Côte Basque 1965” and is re-created in the pilot episode — the series oddly avoids commenting on the purported reason Paley allegedly slept with the unnamed New York governor’s wife. Both Capote’s Women and a 2012 Vanity Fair article suggest that the one thing that eluded the Jewish Paley throughout his massively successful life was acceptance into Wasp society’s schools and clubs. (Even his marriage to the Gentile Babe wasn’t enough.) Paley’s affair with the “Protestant” governor’s wife was supposedly his act of revenge.

Joanne Carson (Played by Molly Ringwald)

She’s not a Swan per se, but Joanne Carson figures prominently in both Feud and in Truman Capote’s real life. She appeared in “La Côte Basque 1965” as “Jane Baxter,” the wife of a famous late-night talk-show host. In reality, Joanne was the ex-wife of the talk-show host of the day: Johnny Carson. According to Capote’s Women, Joanne wasn’t bothered by her mention in the infamous Esquire excerpt — unlike most of the Swans.

In Feud, Ringwald’s Joanne is both Truman’s savior and his enabler: She’s one of the few people who remains friends with Truman after “La Côte Basque 1965,” coming to his rescue when the Swans get aggressive. After

C. Z. Guest clumsily uninvites Truman from her Thanksgiving dinner in the second episode, Joanne ensures the author will have his fill of turkey (and vodka) by bringing him to her California home — New Age prayers and all.

But Joanne’s friendship couldn’t save Truman. It was at her Bel Air home where Capote — who had his own writing room — died in 1984. More than 30 years later, she ended up a bizarre footnote to Capote’s death. According to Capote’s Story, she had the writer’s ashes placed in two urns. One she gave to Jack Dunphy, Capote’s longtime partner, the other she kept for herself. After Joanne died in 2015, her “half” of Capote’s ashes went up for auction with other items from her estate. The ashes sold to an unknown bidder for $45,000.

Ann Woodward (Played by Demi Moore)

Even though Moore’s Ann Woodward is one of the few Truman Capote–adjacent characters who doesn’t get a mention in Capote’s Women, she unquestionably belongs in Feud. The aspiring actress and eventual socialite — she married into old money — was indeed at the center of her husband’s 1955 murder. As Truman dishes during the Paleys’ dinner party in Feud’s first episode, Ann was never charged in William Woodward Jr.’s death, even though she killed him with a shotgun. The official story is that she mistook her husband for a burglar.

Feud implies that Capote and Ann were at odds with each other over the next 20 years with Ann (understandably) furious at the author for never missing an opportunity to destroy her reputation whenever he held court. The series’ version of Truman insists it’s just retribution toward the woman who called him a “fag” behind his back. (This element, along with Feud’s Truman referring to Ann as “Bang-Bang,” seems to have been lifted from Roseanne Montillo’s book about the Truman Capote–Ann Woodward connection, Deliberate Cruelty: Truman Capote, the Millionaire’s Wife, and the Murder of the Century.) This particular grudge culminated with the very public release of “La Côte Basque 1965,” where Capote references a woman named “Ann Hopkins,” believed to be based on Woodward, and flat-out accuses her of murdering her husband.

As depicted in Feud, Woodward died by suicide three days before “La Côte Basque 1965” was published in Esquire, leading to further speculation that she was the Ann Hopkins in question. Feud posits she received an advance copy, but Montillo’s book claims there isn’t any evidence that Woodward knew what the excerpt would contain.

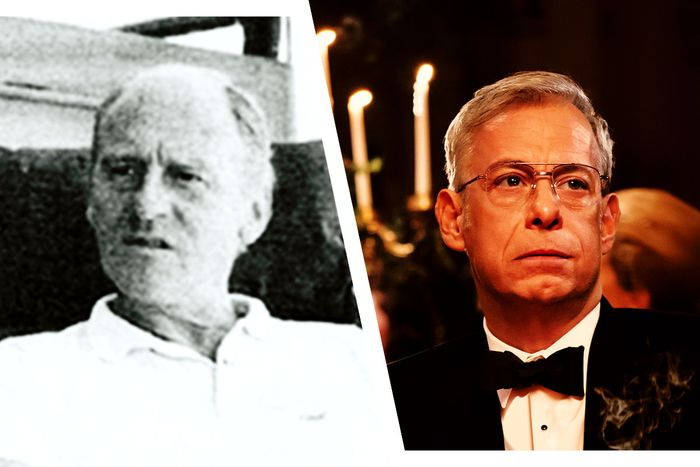

Jack Dunphy (Played by Joe Mantello)

While most of Feud’s characters spend the series, well, feuding with one another, Mantello’s Jack Dunphy is over the drama from the first moment he appears. We’re introduced to Truman’s long-standing boyfriend in the premiere as he walks out on the hot-mess writer in 1975. But though both Truman and Jack have relationships with other men throughout the series, Jack Dunphy was a committed presence in Capote’s life for several decades. After most of the Swans abandoned Truman, Jack stayed loyal, albeit exasperated.

The two men met at a cocktail party in 1948, beginning an on-again, off-again relationship that lasted until the In Cold Blood author’s death. Most of Dunphy’s mentions in Capote’s Women consist of the numerous European jaunts the couple made together as working writers. A 1992 New York Times obituary referred to Dunphy as “Truman Capote’s closest friend and companion for 35 years.” Capote also named Dunphy his chief beneficiary when he died in 1984.

John O’Shea (Played by Russell Tovey)

Resources pertaining to Truman Capote’s lover John O’Shea are few and far between — O’Shea appears in a total of two pages in Capote’s Women — so it’s hardly surprising that Feud takes some major creative liberties with Tovey’s character: John is the mastermind behind Truman turning “La Côte Basque 1965” into one big gossip rag about the Swans. What Feud does get right is Capote and O’Shea’s tumultuous relationship, as well as their New York City bathhouse encounter (though Capote’s Women places that meeting in 1973, two years earlier than Feud’s timeline).

Many accounts, including Capote’s Women, highlight the mutually destructive tendencies of both men, whereas Feud concentrates more on John’s physical abuse of Truman. This is illustrated via a disturbing scene in the second episode, where John brutally assaults Truman during Thanksgiving dinner at Joanne Carson’s house in 1975, landing the writer in the hospital. While the setting and year are changed for the sake of the series’ narrative, Capote’s Women suggests there’s plenty of truth to O’Shea’s abuse: The book documents an eerily similar incident occurring in Miami in 1981.

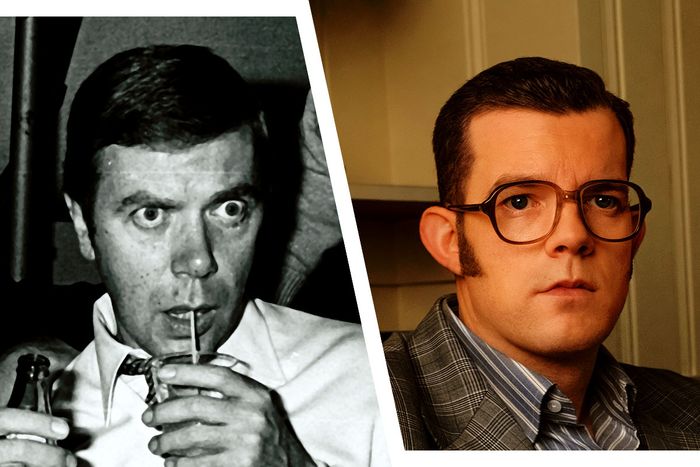

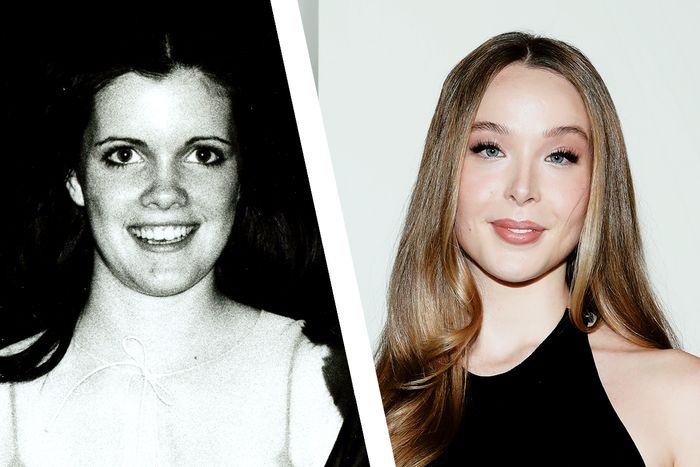

Kerry O’Shea/Kate Harrington (Played by Ella Beatty)

Kate Harrington is a more mysterious member of Truman Capote’s collection of female friends. She receives no mention in Capote’s Women, and Beatty’s portrayal appears to be cobbled together from the 2019 documentary The Capote Tapes and the small amount of press Harrington did for the film. In the fourth episode of Feud, a teenage Kerry O’Shea — the daughter of Truman’s sadistic lover, John O’Shea — shows up on Capote’s doorstep looking for a father figure, a job, and entrée into the author’s glamorous world. At this point, John has not only abandoned Truman but also left his wife and children in a serious financial lurch. Truman takes Kerry under his wing, changes her name to Kate Harrington, gets her some modeling gigs, and encourages her to start journaling about her experiences.

Other than making Kate a little older (most articles say she was 13 or 14 years old when she first reached out to Capote for help; Beatty’s Kate is giving 16 or 17), most of Feud’s Harrington portrayal does track. Unfortunately, her later appearances in the series serve more as a conduit for Truman’s downward spiral, including a creepy, Vertigo-esque makeover in which Truman turns Kate into a Babe Paley clone.

James Baldwin (Played by Chris Chalk)

Although Chalk steals the entire fifth entry of Feud as expatriate American writer James Baldwin, it’s difficult to do a fact-versus-fiction analysis of his one-episode appearance. First of all, there’s no evidence that Truman Capote and James Baldwin spent the day after the publication of “La Côte Basque, 1965” together. Second, “The Secret Inner Lives of Swans” heavily suggests Baldwin’s intense, daylong visit only occurred within Truman’s mind.

Shoehorning James Baldwin into Feud reduces Baldwin, a writer equally legendary to Capote, to a narrative device. This is an author who built his career through unapologetic observations about American race relations, influencing both the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s and Black Lives Matter. He participated in the March on Washington in August 1963 and the Selma, Alabama, march for voting rights in 1965. In 1974, one year before Baldwin and Capote’s fictionalized Feud meeting, Baldwin published the novel If Beale Street Could Talk, about the false rape accusation against a young Black man. (Regina King won an Oscar for her performance in the 2018 film adaptation.)

But Feud doesn’t acknowledge any of this legacy; the closest Chalk’s Baldwin comes to addressing racism is when Truman discusses how the Swans deem the Nicaraguan Bianca Jagger acceptable as a dinner party guest — but not as a houseguest. Whether or not the Fire Next Time author showed up for real or in a dream on that day in November 1975, his sole purpose in “The Secret Inner Lives of Swans” is to give a deeply depressed Truman a shot of tough love, to convince him to stop squandering his talent and to write the rest of Answered Prayers.

Lillie Mae “Nina” Faulk (Played by Jessica Lange)

What would a Ryan Murphy production be without his muse? Lange, who serves as a producer on Feud, pops up throughout the series as Truman Capote’s aimless mother, Nina. With the exception of one upcoming flashback, her appearances are exclusively a representation of Truman’s inner monologue, since Faulk died by suicide in 1954. Lange’s Nina comes off as Truman’s original Swan: beautiful, fashionable, and the author’s biggest critic. She first materializes in Feud’s second episode, while her son drinks himself into a stupor at Joanne Carson’s Thanksgiving dinner. The series uses this opportunity to have Truman reveal both why he drinks (to deal with being a gay man in 20th-century America) and the original intent of “La Côte Basque 1965” (his revenge on society women for shunning Nina).

Since Nina predominantly appears as a hallucination, there’s less expectation of historical accuracy, especially considering she appears only through Truman’s lens. What we do know about her is that, like her son, Faulk struggled with alcoholism. She also, according to Capote’s Women, personified neglect for Truman: Faulk left her 6-year-old son in the care of her Alabama family members in 1930, eventually settling in New York City. She divorced Truman’s father, Arch Persons, in 1931, and married Joe Capote in 1932. Although Truman went to live with his mother and new stepfather in 1933, that early feeling of abandonment never went away.